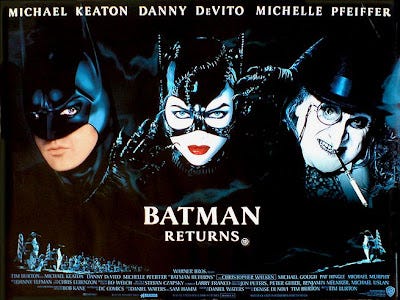

25 Reviews of Christmas #18 - A subtextual analysis of Tim Burton's "Batman Returns," which, for the record, is indeed a Christmas movie

Nothing says Christmas quite like Batman.

Yes, I did indeed just type those words, because today we’re discussing Tim Burton’s “Batman Returns,” the 1992 sequel to the Burton’s first smash-hit “Batman” movie. And before everyone starts saying “Jonathan, ‘Batman’ isn’t Christmas-y,” I’d like to point out that the entirety of “Batman Returns” takes place in the weeks leading up to Christmas, many references to the Holiday are made, and snow drenches every last scene.

It’s a Christmas movie. So there.

It’s also one of the most fascinating creations to ever come out of the Hollywood studio system, so if you’ve ever found yourself baffled by the film’s eccentricities, click-through to read my detailed analysis of the rich subtext many viewers miss (understandably so, as “Batman Returns” is an extremely disorienting experience).

Enjoy! Review after the jump….

The first thing you need to understand about “Batman Returns” if you are to enjoy it is that it is not a Batman movie. Yes, it is technically a Batman movie, as it’s part of the Batman franchise, the title bares his name, and the caped crusader is indeed featured, but if we judge it as a true Batman film, it is an utter failure. Batman isn’t even the main character. He only appears once in the first 45 minutes, and from there on, the Penguin and Catwoman both get far more screen-time, and the story revolves around their arcs far more than Batman’s. If we want to get nitpicky, there are dozens of little inaccuracies that could get the purist in me crying foul, such as a scene where Batman straps a bomb to a thug’s chest and smiles as the man explodes. Batman would never do that.

But that’s okay, because “Batman Returns” isn’t a Batman movie. It’s a Tim Burton movie, and it explores the themes and aesthetics that interest Burton, not Batman. Viewed this way, the film may very well be a masterpiece, albeit an accidental one; the unprecedented runaway success of Burton’s original 1989 “Batman” gave him free reign to do whatever he wanted with the sequel. Indeed, that’s the only reason Burton returned to the director’s chair; while his distinctive visual stamp can be seen in every frame of the first “Batman,” that was a studio project, not a film Burton could pour his heart and soul into. The creative freedom of “Batman Returns,” however, allowed Burton to realize his directorial vision without boundaries, leading to the clearest, most masterful expression of the themes he so regularly explores.

As he so often does in films like “Edward Scissorhands,” “Ed Wood,” or “Sweeney Todd,” Burton turns his gaze towards the outcasts in society. As a highly introspective individual deemed weird or odd all his life, these are the sorts of people Burton relates to, but what makes “Batman Returns” resonate more strongly than many of his other films, for me anyway, is that Burton is able to widen his thematic gaze, examining not just the individual, but society itself, the social forces that create outcasts and the large-scale ramifications of doing so. Burton also strikes an uncompromisingly bleak tone this time around, refusing to pull any punches or shy away from the darker aspects of this important thematic discussion. Through this dark, three-dimensional look at our culture, Burton clearly pinpoints a source for the misery and loneliness so often present in his works, and that source is society itself. In fact, if there’s any one element that clearly distinguishes this from all other Batman stories, it’s that “Batman Returns” doesn’t present Gotham as an entity worth saving. If anything, they deserve what they get, and Batman may be part of the problem, not the solution.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. “Batman Returns” follows four central characters: the Penguin (Danny DeVito), abandoned at birth for his horrible deformities, who returns to Gotham seeking revenge. He joins forces with local millionaire Max Schreck (Christopher Walken doing his delightfully zany Christopher Walken thing), the most vile man in town, who is looking to use his political power to replace the Mayor with someone easier to manipulate. The Penguin, it turns out, fits that bill. Meanwhile, Schreck throws his secretary, Selina Kyle (Michelle Pfeiffer), out a window after she learns a terrible secret about his business, inadvertently creating his worst enemy: Catwoman. At the heart of it all is Batman (Michael Keaton), doing his best to hold Gotham together as all these clashing forces begin tearing it apart.

A brief plot synopsis fails do to the film justice, as it is a complex but expertly constructed web of mystery, double-crossing, evil plots and even romance. The complexity allows Burton and company to explore many aspects of society: the media, the masses, the government, the money, the heroes, the parents, and most importantly, the pariahs. All of it is addressed spectacularly well. The media, for starters, is a constant presence, but Burton isn’t interested in its positive qualities. In Gotham, the media is a force to be manipulated; journalists are out for a story, putting the power in the hands of whoever can best capture the public eye. The Penguin, with Shreck’s guidance, becomes a master of media manipulation, playing Gotham like a “harp from hell.” The masses, of course, eat it all up. They are fickle and fast to change to their minds, too accepting of whatever is put in front of them to be critical consumers of culture, thus giving people like Shreck and the Penguin the power. Shreck himself is a statement about the role of money in politics; his wealth gives him power, and a weak, corrupt government is powerless to stop him from exercising his influence.

What are the results of all these various societal forces? The answer is simple – it’s embodied in the disgusting creature that is the Penguin. He is a classic Burton outcast, the sum total of a fickle culture interested only in what is immediately accessible and easily digestible. Though his deformities inherently make him ‘different,’ there’s no reason his parents (and society at large) couldn’t have raised him well. It may have taken some extra effort, but it could have done. But this is a culture disinterested in going the extra mile, and that lack of critical thinking bites them all in the ass over and over again when the Penguin, a mirror to their own sins, returns to manipulate Gotham. The Penguin may be the ‘villain,’ and he certainly does some horrible things, but as the film goes along, it’s clear that his creation was inevitable. A Gotham this misguided was bound to produce a dangerous force like this sooner or later. Enabling men like Max Schreck, in fact, only gives the Penguin extra power.

The most fascinating element present in “Batman Returns,” however, is the underlying feminist theme, courtesy of Catwoman. In the film’s early scenes, Selina Kyle is depicted as another victim of a world gone wrong, a suppressed working woman stuck in a dead-end life that, thanks to cultural sensibilities about gender roles – her mother, for instance, expresses extreme dissatisfaction that Selina isn’t married yet, and Selina herself seems to have had this thought beaten into psyche over time – probably isn’t going anywhere any time soon. Gotham is clearly depicted as a man’s world – the people in power are all men, as is the city’s chief defender – and though Selina is clearly a smart, capable woman, this overwhelming patriarchy is keeping her down. The theme couldn’t be made any more clearly than it is when Max Schreck, exerting his male dominance, shoves Selina out of a window just to keep her quiet.

But the fall doesn’t kill her. Instead, it draws out all her latent strength, and Selina becomes the latex-clad Catwoman, a fiery embodiment of all male sexual urges and desires destined to raise hell on the men that conjured such images. And raise hell she does, blazing a gleefully unhinged anarchist trail through the city. Though Pfeiffer’s performance is chiefly remembered for being “sexy,” I don’t think Catwoman is meant to be interpreted as a sex symbol at all. She is, on the surface, what the vain male who created her wanted (pay close attention throughout the movie to how male sexual urges are presented – it’s never flattering), but what lies underneath is the unbridled horror such lopsided cultural gender roles actually create. Catwoman exists to even the odds, not just to take revenge on men like Max Shreck, but to teach all of Gotham a lesson. Like Batman, she too is a symbol, one the city won’t soon forget.

In my interpretation of the film, Selina is the true protagonist. As Catwoman, she obviously doesn’t do too many ‘nice’ things, but she is a product of her environment, and even at her worst, we have an emotional attachment to her that doesn’t exist with Batman or the Penguin. In fact, I believe her presence automatically demystifies Batman – he oversees the security of the city with a staunchly male point-of-view, an angle Catwoman immediately contrasts. In one scene, she even scolds a damsel in distress for leaving her rescue up to Batman. One could argue that, as presented in “Batman Returns,” Batman himself is part of the larger cultural problem Burton identifies, and even though Catwoman’s actions are often villainous, she is the natural opposite force created by a society that allows Batman to operate with such authority. “Batman Returns” boils down to an archetypical battle between Batman and the Penguin, with Catwoman, the non-archetypical outlier, caught in between, and as such, it’s her decisions and actions that carry the most thematic weight.

Michelle Pfeiffer is terrific in the role, and I’m sad she rarely gets the amount of credit she deserves for bringing this character to life. The whole cast is excellent, of course – Michael Keaton may always be the definitive live-action Bruce Wayne in my book – and the technical merits of “Batman Returns” are unparalleled. The production design, already amazing in the first film, rises to dizzying new heights here. Burton’s stylized Gotham is gorgeous, realized all through practical effects, and it’s impossible to spot the seams in the craftsmanship. Danny Elfman’s score is simply breathtaking, the second-best work of his career, only behind “The Nightmare Before Christmas.” He develops and expands upon themes from the first movie, composes many new pieces, and maintains a constant sense of energy and momentum.

What makes “Batman Returns” so remarkable is what Burton chooses to do with the then-unprecedented technical possibilities at his disposal. As my thematic analysis has hopefully demonstrated, he chose to go in the most unconventional route possible, examining, through the dark prism of Gotham, all the societal forces that create outcasts. Maybe I’m just a pessimistic person, but as I see it, the ultimate message is that Gotham – left in tatters at the film’s conclusion – more or less deserves what it gets for perpetuating such unhealthy practices. A society that creates and banishes ‘outcasts’ should expect eventual ramifications. That’s not to say “Batman Returns” isn’t without its moments of lightheartedness – there are dozens of laugh-out-loud moments and winkingly self-aware puns – but at its core, “Returns” is comprised of Burton’s dark ruminations on the themes that have defined his career.

Need further proof? Take a look at the time of year Burton chooses to set the story – Christmas. A time when we are supposed by happy, loving, together, and accepting. But we all know that so much of the holiday season is a sham, either commercially or culturally, and that’s a central tenant of “Returns.” Those in power attempt to use Christmas as a shield, and those hypocrisies brilliantly highlight the grimy societal flaws at the heart of the story.

In that way, “Batman Returns” really is a Christmas movie. A relentlessly dark, complex, and challenging one, but a Christmas movie nevertheless. At the very least, it’s got more Christmas in it than Batman.