An Ode to the Harry Potter Film Series: A Cinematic Achievement Worthy of Reevaluation

It may sound weird to claim that the highest-grossing film series of all time (minus the interconnected sprawl of the Marvel Cinematic Universe), a franchise that is as iconic as it is beloved by millions worldwide, is creatively underrated, but here’s the thing – I think the Harry Potter films are, as works of cinematic art, genuinely undervalued.

It’s something that gets lost in discussion of the films as cultural phenomena or as adaptations, where the works themselves become drowned in discussions about – or discussions amongst – fandom. As far-and-away the most lasting (and most often imitated) of the wave of 2000s ‘young-adult’ properties – a wave it is centrally responsible for creating – Harry Potter is so big and culturally ingrained it can become difficult to separate the art from the hype, the object itself from the cultural furor surrounding it.

And just as I think J.K. Rowling probably isn’t recognized enough in literary circles for just how beautifully and uniquely-written her creations are, so too have the Harry Potter films become underappreciated as outstanding works of mainstream cinematic art. These were spectacularly-made films, produced with a level of artistic passion and cinematic verve we simply do not see much of in mainstream Hollywood ‘blockbusters,’ even just five years past the release of the last movie. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, a ‘spin-off’ of the original franchise reuniting much of the behind-the-camera talent – including, perhaps most significantly, director David Yates, who helmed a full half of the original eight movies – has only looked better and better with each second of footage released, and to me, a big part of that is how cavernous the gap feels between mainstream Hollywood in 2016 and mainstream Hollywood through the decade of Harry Potter (2001 – 2011). The Harry Potter movies exemplified an arguably now-dormant belief in throwing the best filmmakers and craftspeople behind a major tentpole, not just making a visual product ‘good enough’ for the masses, but a cinematic experience truly worthy of the surrounding hype and excitement. You saw it also with Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films or Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy – properties that, in another time and under most expectations of Hollywood, would have been produced with significantly less artistic might behind them. If you think of the now-dominant trend of superhero movies, we have WB – the company behind Harry Potter and Nolan’s Batman – shitting the bed with downright horrible filmmaking, or Marvel, which produces very good and very fun movies, but often without the sheer level of craftsmanship that went into a Harry Potter. And the less said about the majority of the Potter knock-offs, the better (only The Hunger Games films, of this trend, aspired to similar heights).

In the immediate post-Potter aftermath, I think the industry learned many of the wrong lessons – that a successful long-running franchise was more about heavy marketing and a long-term game-plan that genuine bottom-up filmmaking. People forget that Potter evolved on film organically, moving through directors before it truly hit its stride, and that nobody in the industry was betting this thing would work over ten years and eight films right out of the gate. But as many of the project produced in the shadow of Potter have burned bright only to fizzle quickly (if they burned at all), I am starting to see that some in Hollywood are beginning to learn the real lessons of the franchise. Look no further than Disney’s approach to Star Wars, where they have been hiring genuinely talented filmmakers with recognizable visions, and stacking the craft ranks with heavy hitters in terms of cinematography, editing, production design, music, and more. So much of the key to the Potter magic was that WB invested in these movies as though they were golden-age Hollywood prestige films. They demanded the best of everything, and didn’t settle for less. I think Disney is taking that kind of care with Star Wars, and given the reaction to The Force Awakens and the early excitement for Rogue One, it clearly matters. It makes a difference. Harry Potter was proof.

And I think Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them looks to be a stirring reminder of why those lessons are important. From the trailers alone, this appears to be a movie with more palpable atmosphere, creativity, and cinematic weight than most of what has passed for Hollywood blockbusters over the past few years. It, alongside Rogue One, feels like a resurgence in a wave of movies made in the Potter model, where filmmaking seemed to come first – a wonderful hat trick for a multi-billion dollar franchise where the art object itself can paradoxically seem to be the least important consideration. If I am excited for Fantastic Beasts – and I am – it’s less because I’m a big Harry Potter fan – which, obviously…I mean, just look at this madness – but because it is following in a lineage of truly impressive cinematic accomplishments, a decade’s worth of blockbusters that dared to dream bigger and execute at a higher level that most mainstream Hollywood products of my lifetime.

After the jump, allow me to elaborate…

The Filmmaking

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince: DoP Bruno Delbonnel

If you want evidence of how well-made the Harry Potter films are, look no further than the list of cinematographers who worked on the franchise:

John Seale (The Sorcerer’s Stone)

Roger Pratt (Chamber of Secrets and Goblet of Fire)

Michael Seresin (Prisoner of Azkaban)

Sławomir Idziak (Order of the Phoenix)

Bruno Delbonnel (Half-Blood Prince)

Eduardo Serra (Deathly Hallows Parts 1 and 2)

That is a downright staggering line-up of heavy-hitters. Seale is an industry legend who most recently came out of semi-retirement to shoot the groundbreaking Mad Max: Fury Road. Pratt has an extensive body of work full of recognizable titles, including Tim Burton’s Batman – a visual landmark if nothing else – and three significant collaborations with Terry Gilliam (Brazil, 12 Monkeys, The Fisher King). Idziak was a frequent collaborator of the great Polish direct Krzysztof Kieslowski, and shot Dekalog 5, The Double Life of Veronique, and Three Colors: Blue, three of the most visually stunning films ever made (Veronique also happens to be one of my ten all-time favorite films). Delbonnel had already made a name for himself in France before Potter – he shot Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amelie – and after Half-Blood Prince (the only Potter film to earn an Oscar nomination for Cinematography) his reputation has only grown, highlighted by his incredible work on the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis.

I could wax poetic about these six men all day, before even getting to talk about their work on the Potter series. Every one of them (save Michael Seresin) is an Oscar winner or nominee, and each carries a clear lineage from art cinema around the world, the kind of aesthetic experience and voice that makes the Potter movies so visually sophisticated and stunning. No other major Hollywood franchise in the 2000s was so artfully shot or visually playful (with the possible exception of the Jason Bourne films, though those obviously never played for the same scale of audience). From Seale’s warm initial invocation of this wondrous fantasy world in, to Pratt’s steady capture of a complex magical status quo, to Seresin’s achingly beautiful work with cool colors and wintry Scottish landscapes, to Idziak’s tangible and textured push towards a more contemporary immediacy, to Delbonnel’s downright audacious use of subdued lighting and unnatural, sepia-flavored colors, to Serra’s chilling employment of handheld cameras and deep, haunting black levels, the Harry Potter films are a master-level crash-course in what defines outstanding cinematography.

Given how far David Yates and his Directors of Photography were allowed to go in the final four films – seriously, Half-Blood Prince is one of the most remarkable visual inventions ever marketed on the sides of buses and billboards – one only wonders how much further Seale and Pratt, for instance, could have pushed things if they too were working under less restrictive conditions (I say this not to deny that their films are gorgeous – they are – but only to recognize that they stay closer to conventions than the later pictures). My favorite of the Potter films – both visually and overall – is Prisoner of Azkaban, the sole entry directed by the great Alfonso Cuarón, and I think what he and Michael Seresin accomplished there continues to be an underrated accomplishment. The color scheme in particular is one of my favorites ever employed in a live-action production; an extremely cool, autumnal palette, yet one that doesn’t sacrifice a hint of depth in the colors, something that most films looking to ease up on brightness wind up losing. It also features some of Cuarón’s typically playful photographic experimentations, such as the scene in Lupin’s classroom that is shot entirely as though through a mirror – a detail I never notice until later viewings.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azakaban: DoP Michael Seresin

In short, I don’t think there’s any extended franchise in Hollywood history – with the possible exception of James Bond which, as always, feels like it belongs on an island to itself given its age and mutability – that I would hold above Harry Potter when it comes to cinematography, and if that sounds like a bold claim, go ahead and watch any of these movies again, study their visual design closely, and then try to seriously argue the point.

I think the cinematography is the most remarkable aspect of the Potter films, but it achieves that distinction in part on the backs of all the other achievements in craft that fuel the Potter movies. No single person was perhaps more important in bringing J.K. Rowling’s world to life than Production Deisgner Stuart Craig, who stuck with the franchise through all eight films and created perhaps the most distinctive and fully-realized fantasy landscape ever captured on celluloid. Just think of the sheer number of sets Craig and his team had to create – not just Hogwarts and all its many halls and classrooms and secrets (a historic achievement in and of itself), but the Dursley’s home, the Weasley’s Burrow, Gringotts and Diagon Alley, the Chamber of Secrets, the town of Hogsmeade, the Shrieking Shack, the three venues of the Triwizard Tournament, #12 Grimmauld Place, the Ministry of Magic, Voldemort’s Oceanside cave, and all the way back around to a destroyed and decimated Hogwarts in the final movie.

This is only a partial list, and yet when I name any of those places, I imagine any reader with even a passing familiarity of the Potter movies can picture the location clearly in their mind’s eye. Craig’s evocations did not always match what I imagined when reading the book; most of the time, they surpassed whatever I could conjure, and the overall texture of Harry Potter on film – a world that feels so unbelievably palpable, old and withered and thoroughly used and lived in – is a significant artistic accomplishment in and of itself. Craig garnered Oscar nominations for four of the eight films, but never a win – one of the greatest oversights in the history of the Academy Awards.

The Ministry of Magic - Production Design by Stuart Craig

I have only highlighted a few of the most significant craftspeople here, but the list goes on and on, and the individuals most closely associated with certain roles on Potter – like Jany Temime, Costume Designer for the last 6 films, or Mark Day, editor for all 4 Yates entries – have unsurprisingly gone on to continue doing great work in the industry. And if the visual effects started out on the rougher end of things – compare the Troll in Sorcerer’s Stone to the Troll in Fellowship of the Ring, released the same year – the Potter team quickly got its act together, and by the time of Deathly Hallows, the filmmakers were so good at conjuring seemingly casual acts of magic that at no point did the VFX ever threaten to take one out of the experience; on the contrary, they continually enhanced the sense of immersion.

And then, of course, there are the directors themselves, a group who can seem a little underwhelming when compared to some of the names filling the crafts ranks. No one is ever going to claim Christopher Columbus is a great (or even particularly good) filmmaker, Mike Newell’s talents chiefly lie elsewhere, and while Yates had some smaller-scale successes before Potter, he is (and will probably forever be) chiefly recognized as part of the Potter phenomenon. Of the four men to direct a Potter film, Alfonso Cuarón is the only one we can reasonably say is a great figure in world cinema, and it’s no surprise that his film, Prisoner of Azkaban, did more than any other Potter movie to set the tone and visual style going forward. But Yates showed both consistent and exponential improvement as a mainstream blockbuster filmmaker over his four franchise outings – to the point where there is no one else I would frankly trust more with Rowling’s material – and if Columbus hasn’t done many great things outside of Potter (and if his Potter films are by far the weakest of the lot), it would be doing him a disservice to ignore what a legendary cast he assembled or what a great team of collaborators he put together.

There is, of course, one crafts category I haven’t dived into yet, because it honestly deserves its own category – and that is, of course…

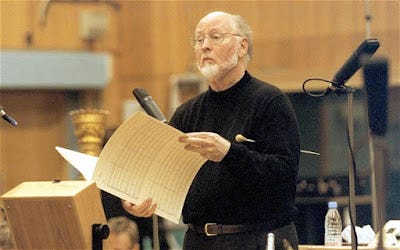

The Music

Composer John Williams

The Harry Potter movies never cared much about visual continuity between films – a precedent Cuarón set by essentially redesigning every part of the Hogwarts grounds for his entry – but thanks to Stuart Craig’s steady hand in the Art Department, it’s undeniable that the films have an overall cohesive sense of aesthetic. The same cannot really be said for the music, and while it would be easy to attribute that to John Williams’ departure after Prisoner of Azakban and the employment of three further composers to finish out the series, the truth is even Williams himself reinvented the films’ sonic palette during his brief tenure with the franchise.

Getting Williams to compose Sorcerer’s Stone was obviously one of the most important steps towards legitimizing Potter as a film powerhouse, and his score for that film is, rightfully, legendary. Its main theme is iconic, its musical scope and scale is vast, and its impact on the atmosphere and tone of the film is incalculable. As beautiful and listenable as it is, however, I wouldn’t argue Sorcerer’s Stone (or Chamber of Secrets, which Williams is credited for but had no major role in, as it consists mainly of recycled cues from the first film) represents one of Williams’ best scores. It’s arguably too dense, layered so thickly over the film and its characters that it can, at times, have a suffocating effect.

One senses Williams felt the same way, for when he came back for Prisoner of Azkaban, he threw out everything he had done before – save the basic melody of “Hedwig’s Theme” – and started from scratch. It’s not just that he composed a large host of all new themes, either – it’s that the basic style of instrumentation and musicality he employed in Sorcerer’s Stone was tossed out the window, replaced with a musical palette far more diverse and evocative. From the Waltz written for Aunt Marge’s Big Mistake, to the avant-garde insanity of the Knight Bus scene, to the achingly gorgeous cues written to symbolize Harry’s reflections on the past, to that glorious drums and strings piece that illustrates Buckbeak’s first flight, the Prisoner of Azkaban score isn’t just good – it’s one of cinema’s all-time greatest composers working at the absolute top of his game, with the kind of passion and invention one would normally expect of someone far younger and more eager to make a name for themselves.

I will not deny that there is a large part of me that wishes Williams could have seen the series through to the end – that Prisoner of Azkaban would not have been a culmination of his Potter efforts, but the next step in a grand musical evolution. Not only would it have given the series a more cohesive musical identity, but I think it would have brought out the best in one of cinema’s most treasured artists.

But in the world in which we inhabit, Williams did depart early on, and it would be petulant to dismiss just how well his successors wound up doing. Patrick Doyle’s score for Goblet of Fire is probably the most ‘different’ of any Potter movie – just as Goblet of Fire itself stands out the most in terms of wonky pace and tone – but I like it a lot, and I think Doyle’s ability to blend a sense of grandeur and playfulness in his music is one of the best things about the film. David Yates brought on longtime collaborator Nicholas Hooper for Order of the Phoenix and Half-Blood Prince, and Hooper had a ball with the job, writing some iconic compositions of his own (“Fireworks,” anyone?) and riding the wide tonal shifts of those two movies with incredible expertise. Finally, the great Alexandre Desplat finished out the series with the two most quiet and somber scores for the series, and while Desplat is never at his most comfortable when writing for big, bombastic action scenes, the sense of grounded emotional reality he brought to those two scores make them some of the greatest highlights of the Potter experience.

(And it should be noted that while all of these scores are good, none of them – including Williams’ – are as perfect for the world of Harry Potter as what composer Jeremy Soule conjured for the first few video games. Seriously. Go to YouTube. Listen to Soule’s compositions. Click around to the other recommended links. That is Harry Potter exemplified through music. I love it more than I can say.)

The Adaptation

Screenwriter Steve Kloves & Author J.K. Rowling

The foundation of every movie is its script, of course, and while there are problems here and there with the adaptations provided by Steve Kloves (and, for the fifth film, Michael Goldenberg), I think the Potter films are generally exemplary of how to craft a powerful cinematic adaptation. The first two films are, of course, far too slavish to the source material, and the resulting pace is a mess; but Kloves had a great handle on these characters and Rowling’s themes from the beginning, and once he was allowed to experiment and play in this world more, he generally struck gold.

In the best Potter films – which are, to me, Prisoner of Azkaban, Half-Blood Prince, and both Deathly Hallows – Kloves tended to identify a core theme or atmospheric identity from the book and build everything in the film around that basic idea, rather than trying to cram every incident from Rowling’s increasingly long tomes into a single film. Prisoner of Azkaban is, at its heart, about the pain of loss and the power of memory, its world a representation of the liminal emotional state in which Harry finds himself. Half-Blood Prince, one of the darker books, is the funniest film, as Kloves and Yates played off the awkward coming-of-age undercurrent in Rowling’s text and ran with it, crafting a story that set the pressures of growing up and navigating social circles against the fog of an impending war, drawing numerous insightful (and uncomfortable) parallels therein. And Deathly Hallows, while getting to include more from the books thanks to its expanded run-time, still excises all but the essentials, the first film a dark tone poem about three friends lost in a world they no longer recognize, the second an intimate war epic about the piercing pain of letting go and moving on.

Kloves sometimes stumbled. Goblet of Fire is the messiest script of the lot, as forcing Rowling’s complex 700-plus page tome into a 2.5-hour movie proved too big a challenge for even this talented team. And while Michael Goldenberg did undeniably impressive work transforming the longest Potter book into the shortest Potter movie – Order of the Phoenix – the resulting film, while enjoyable on a number of fronts, feels lighter-weight and less-essential than it probably should.

But if there are things lost here and there along the way, so much is gained in terms of character and atmosphere. In the films I mentioned above, Kloves and his directors weren’t afraid to deviate far from Rowling’s path, inventing character moments wholesale that often did a better job illustrating motivations and emotions than a ‘straight’ adaptation ever could. I often think of how Kloves and Cuarón handle Harry’s scenes with Remus Lupin (none of which follow the letter of Rowling’s text, but summon the spirit of her words so beautifully), or the scene from Deathly Hallows where Harry tries to cheer Hermione up following Ron’s departure with an impromptu invitation to dance.

The best of these inventions comes in Half-Blood Prince, in a scene where, after being spurned by a clueless Ron yet again, Hermione breaks down in Harry’s arms, baring not only her soul but peering insightfully into his. “How does it feel Harry? When you see Dean with Ginny?” Harry demurs, not knowing what to say. “I know,” she continues. “I see the way you look at her. You’re my best friend.” That last line breaks my heart, every time, just as Ron barges in with new girlfriend Lavender, only to be sent away by Hermione. She collapses, and Harry puts an arm around her. “It feels like this,” Harry says softly, repaying her honesty with a touch of his own. It is a brilliant, searing moment in a film full of stupendous character work, and emblematic of what the Potter films could at their best achieve in terms of character and mood.

The movies are not the books, and yes, it is impossible to deny that Rowling’s novels are the definitive way to experience this story. But I would add that the books are also not the movies, and for moments like the one described above, these films managed to stand on their own in a way few adaptations do, taking on a life and vitality that stands boldly apart from, if not necessarily above, what Rowling achieved in print.

The Acting

Here is the one element of the films every person on the Planet Earth, whether or not they care for Harry Potter, was an absolute masterstroke – and yet, I would still argue we kind of take for granted just how amazing the acting in these movies was. That this assemblage of legendary British talent was housed under one roof, and that the ranks just kept expanding and expanding, as though Potter had its own seismic orbit that continually brought in the best of the best, is a pretty unique feat in the history of mainstream cinema.

So we have Dame Maggie Smith, embodying Professor McGonagall so completely it is impossible not to connect her image with the character. We have not one but two terrific takes on Professor Dumbledore, in the late Richard Harris, who exemplified the warm age and wisdom of the character, and Michael Gambon, who brought fiercely to life the character’s playful wit and determination. We have Robbie Coltrane strolling straight out of our imaginations and onto the screen as Hagrid, and Kenneth Branagh making Gilderoy Lockhart every bit as insufferably likable as he should be. We get Fiona Shaw and the late Richard Griffiths as the perfect embodiment of the Dursleys, sadly underutilized past the third film. We have David Bradley doing sorely underappreciated work as Argus Filch, presaging his later-in-life career resurgence in shows like Broadchurch. We get Mark Williams and Julie Walters playing the world’s greatest parents as Mr. and Mrs. Weasley, and Brendan Gleeson as a perfectly off-putting Mad-Eye Moody. We get David Thewlis as Remus Lupin and Gary Oldman as Sirius Black, two sides of an emotionally broken coin. We have Ralph Fiennes crafting one of the best big-screen villains ever in Lord Voldemort, and Helena Bonham-Carter going full-on crazy as underling Bellatrix Lestrange. We have Jim Broadbent conjuring a Horace Slughorn very different than the one I pictured in the book, but altogether fascinating and delightful nevertheless, and Imelda Staunton crafting a Delores Umbridge every bit as terrifying as one could wish. And throughout the series, we have appearances by the likes of John Hurt, Jason Isaacs, Helen McCrory, Timothy Spall, David Tennant, Peter Mullan, John Cleese, Bill Nighy, Emma Thompson, and Ciarán Hinds, plus discoveries like Natalia Tena and Domnhall Gleeson.

And most importantly, we have the late, great Alan Rickman, doing the best work of his distinguished career in one of the most perfect pairings of actor and character imaginable. His Severus Snape is the stuff of legend – just as it should be.

Whew. That is a hell of a cast – and by no means did I list every significant actor to pass through the doors of Hogwarts. Nor, so far, have I listed any of the child actors who turned out to be major discoveries in their own right – the young men and women who not only provided the main emotional and narrative weight of the series, but who evolved over the course of these eight films into some of the best performers of their generation. That Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson were all perfectly cast right out of the gate is amazing in and of itself; that each of the three continued to improve with each passing film, evolving from spirited child actors to uniquely talented adults, is something of a minor miracle. Watson emerged early on as perhaps the most promising of the three, and it is no surprise whatsoever that she has taken the world by storm in the years since Potter ended. Radcliffe has worn the weight of being Harry Potter admirably, leveraging his fame for an idiosyncratic and experiment-prone career that has led to some wonderful performances and collaborations. Rupert Grint has had the least-notable post-Potter career of the three, but that A) feels perfectly appropriate from the guy who played Ron Weasley, and B) does nothing to negate how much levity and soul he brought to each of the films.

These kids were great – so much so, in fact, that once David Yates took over, he essentially turned large swaths of his films over to coasting on the naturalistic and nuanced interactions they were capable of. And it worked. Harry Potter boasts perhaps the greatest extended adult cast ever assembled for a motion picture series; that it also introduced us to a generation of young performers who may very well one day be just as significant in their own right is an accomplishment that will never stop wowing me.

In Conclusion…

At the end of the day, what J.K. Rowling accomplished in text is a singular achievement for literature, and those books will clearly endure far past any of us. She created a world all her own, with an unmistakable voice and tone, and I think anyone who cannot recognize the skill she exhibited as a writer of character, voice, and world-building is simply being petty. The books are, as I have said, the definitive Harry Potter experience, and I will treasure them always.

But in these eight films, an enormously talented team of filmmakers took that material as it was being released and turned it into a cultural phenomenon all its own, one that didn’t merely ride the coattails of the books but became, over the course of a decade, its own wonderful thing – and to me, all these years later, I can love and embrace both versions of these stories, to the point where many of the details I used to keep separate between the two have blended, just as they clearly have for Rowling herself as she embraces cinema as a way to extend her written universe. These films are a special achievement, an important achievement, and the release of Fantastic Beasts in theatres feels like a moment for the world of Potter to return and show everyone else in Hollywood how this kind of franchise world-building is done. There are many, many better movies than Harry Potter – I recognize that. But under these specific conditions, with the eyes of the world watching and a demanding schedule that would (and did) scare most directors away, I would argue that what Harry Potter pulled off is not only something to be cherished, but something to learn from, an artistic achievement that has important lessons for future generations.

Tomorrow, we shall see if Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them can recapture the magic. I’ll be there, first in line, to find out. Whatever comes next, it’s good to have Harry Potter back on the silver screen. Its presence has been sorely missed.

Follow author Jonathan Lack on Twitter @JonathanLack.