An Appreciation of Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai”

Since there’s no way I’m wasting my time (or yours) on “Battleship” or “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” this weekend, I decided to spend the first free Friday I’ve had in some time and sit down to watch a movie I’ve always wanted to see, but has somehow eluded me my entire life: Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai.” Believed by many to be the greatest film of all time, and acclaimed by everyone else as one of the greatest, it was a truly revelatory experience to finally witness Kurosawa’s masterpiece. I find that a lot of classics really can’t live up to their own inflated legacy, but “Seven Samurai” gripped me from the very beginning and kept me glued to the screen for the fastest three-and-a-half hours I’ve ever sat through. To say I now understand the incredible amounts of acclaim the film has carried with it for nearly sixty years would be an understatement.

So today, instead of reviewing the latest piece of Hollywood garbage, I’d like to discuss one of cinema’s most significant masterworks, and after I’ve said my bit, I’m excited to hear what everyone else has to say on “Seven Samurai” in the comments section. Continue reading after the jump…

Japanese poster for "Seven Samurai"

“Seven Samurai” is definitive proof that it is not the story being told, but the execution of that story that creates compelling drama. The film’s narrative is not what one would call ‘high-concept,’ nor even complex: A group of roving bandits are intent on raiding a sixteenth-century village, so the inhabitants decide to hire a team of Samurai to defend their Barley. That’s it. That’s all the synopsis one needs to understand what “Seven Samurai” is about, and though this story has been the core influence on countless imitators, from “The Magnificent Seven” all the way to “A Bug’s Life,” it’s not the modest plot, but the astonishingly profound way Kurosawa tells the story that makes “Seven Samurai” a masterpiece.

It begins with Kurosawa’s mastery of what I believe to be the most important element of storytelling, let alone filmmaking: the characters. Without significant human touchstones – figures that fascinate, move, or inspire us – one cannot become invested in even the greatest of stories, and I think it is clear that the largest contributor to the film’s cherished status is its vast, deep, and entirely enthralling cast of characters. Forget the titular samurai for a moment, and consider what Kurosawa and the cast do with the villagers themselves. It is not easy to create characters that evoke the casual, circadian toil of everyday life, but from the opening moments, a subtle but powerful empathy for the peasants defines the viewer’s emotional attachment to the proceedings.

The pain of these people’s lives is the palpable constant that ties every scene together, lying in the sad, mournful eyes of the village elder, or the fierce fighting spirit of grieving husband Rikichi, or in farmer Manzō’s desperation to shelter his daughter’s pride. Personally, I find the timid old man Yohei to be the most compelling of all the film’s characters, samurai or no, because his attitude towards life and Bokuzen Hidari’s moving performance provide the clearest expression of how these villagers suffer. Yohei is so used to losing, to living a life of heartbreak and despair, that he can scarcely imagine a gentler existence; a scene in which he softly but passionately laments the theft of a small pot of rice he was entrusted with – the only ‘wealth’ he possessed – positively devastates me. We wish to embark on the film’s epic journey because there are meaningful stakes, and those stakes only matter because we know and care about the villagers so well. Kurosawa never forgets this; the last scene before the climactic battle is entirely devoted to exploring the misery Manzō feels about his daughter’s romantic affair, and the heroic Kambei’s final observation is that “the winners are those farmers, not us.”

But of course, the Samurai cannot be forgotten, as they are, perhaps, the most compulsively watchable team of experts in cinematic history. Kurosawa’s influence on the spaghetti western, the war epic, the action genre, “Star Wars,” and the like are well known, but I also imagine the modern heist flick wouldn’t be the same without the team dynamics pioneered in “Seven Samurai;” the appeal of films like “Ocean’s Eleven” lies in watching several large personalities plan and execute a risky undertaking together, and “Samurai,” of course, did that first.

It is truly amazing how distinct and fascinating – or just downright fun – each of the seven Samurai are individually, and one of Kurosawa’s wisest moves is to devote the entire first hour to putting the team together. We meet each of the Samurai in ways that succinctly yet powerfully summarize who they are, receiving riveting primers on their respective skills and personalities: Katsushirō is the young, enthusiastic warrior begging for Kambei’s instruction; Heihachi chops wood to make a living and maintain his physical skills; Kyūzō’s short, deadly duel with a weaker man immediately establishes him as the film’s resident badass; and the iconic Kikuchiyo appears to the group drunk, his initial dishonesty revealing deeper, heartfelt ambitions and an unstoppable spirit. It’s Kambei’s legendary introduction, though, that first kicks “Seven Samurai” into high gear. In a breathlessly exciting and intriguing sequence, he disguises himself as a monk to save a child from a kidnapper, creating, as Roger Ebert notes, “the long action-movie tradition of opening sequences in which the hero wades into a dangerous situation unrelated to the later plot.”

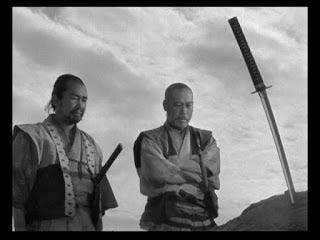

Toshiro Mifune as Kikuchiyo

And Kambei is one hell of a hero. Played beautifully by longtime Kurosawa collaborator Takashi Shimura, he is my favorite of the Samurai, exuding grace, honesty, kindness, and a deadly strategic mind. He is such a quietly commanding character that he demands the viewer’s respect despite his fictional status. I’m sure every member of the group has been named the ‘favorite’ by one audience member or another – I could just as easily argue that Kyūzō is my favorite to watch if, for nothing else, the sequence in which he fearlessly rushes behind enemy lines to steal a musket – but Kikuchiyo is the most universally beloved, and for good reason. Kurosawa gave celebrated actor Toshirō Mifune free reign to do whatever he pleased with the character, and Mifune did the director proud by crafting a once-in-a-lifetime screen presence equal parts funny, tragic, and fierce. If the villagers are the heart and soul of “Seven Samurai,” Kikuchiyo and his many flaws and strengths is the spirit of the eponymous team itself, a concept immortalized in his symbolic triangle on the group’s flag.

“Seven Samurai” is undoubtedly long – at 207 minutes, it outpaces most films an ordinary viewer will have seen – but few films use length to such great advantage. Though the film is an epic, I would argue it is not one of narrative scope, but of character; those 207 minutes are primarily devoted to learning everything we can about who these people are and how they interact, developing strong bonds between the cast and the audience. The level of investment we have in these characters by the time the climax rolls around would be impossible to achieve in a shorter film.

That level of investment, in turn, fuels the string of awe-inspiring action sequences found in the film’s final hour. Though hundreds of films have used the language “Seven Samurai” created when staging their own set pieces, the power of “Samurai’s” action has not diluted one iota in the time since its release. The battles are brutal, captivating, and visually breathtaking, a testament not only to Kurosawa’s incredible staging – notice how he has Kambei literally use a map in planning the defense to help the viewer interpret spatial relations – but to the emotional connection we have to the outcome of each skirmish. Several of the biggest character payoffs come in the heat of battle, such as Yohei finally finding his courage when Kikuchiyo leaves him to defend the post, or when Kikuchiyo himself refuses to let a bullet to the stomach prevent him from cutting down the bandit leader. Action and character development have seldom been so inseparably mixed.

The film’s technical merits are, of course, awe-inspiring at every turn. I have rarely encountered such gorgeous cinematography; each shot is perfectly and profoundly framed, from still, simple shots of characters conversing to long, complex takes where ongoing action is surveyed without a single edit. During Kikuchiyo’s final stand, Kurosawa keeps the camera a few feet away from the interior where the Samurai fights, but tracks along in tandem with Kikuchiyo’s movements, creating a hauntingly beautiful motion that is forever etched in my cinematic memory. It was a bit sadistic towards the cast to set the final battle in the pouring rain, but visually, the choice couldn’t have been better, as every image in that sequence is a treasure trove of compositional riches. The film makes such effective use of black-and-white throughout that I am sure it would be a lesser work had Kurosawa the resources to make it in color. Fumio Hayasaka’s musical score is a character unto itself, softly punctuating the mounting dread or despair of certain scenes with a simple, pounding drum beat, accentuating the playful nature of Kikuchiyo’s character with an imaginative, fun motif, and using horns and regal patterns to underline the film’s exploration of honor.

“Seven Samurai” is the exceedingly rare film that transcends the time and place it was made to suggest universal experiences of friendship, loyalty, fear, courage, and community. From beginning to end, there are characters, emotions, and visuals on display here that will move any viewer lucky enough to come in contact with the film. I immediately wished to re-watch the movie the first time I saw it, knowing my appreciation of the film’s riches would grow exponentially the more time I spent with it, and I suspect that eagerness will only expand the longer I keep “Seven Samurai” in my life. When one comes in contact with a film this accomplished, it underlines why one fell in love with cinema in the first place. “Seven Samurai” is, without a doubt, a testament to all the incredible things this medium can accomplish at its very best.

Now it’s your turn: if you love “Seven Samurai,” sound off in the comments and tell me why. Favorite character? Favorite scene? Favorite speech? Get to typing!