CATS, or the 120 Minutes of Sodom

A love letter to what’s sure to be a new cult classic

What makes a movie a cult classic? Not in the casual sense of the phrase, where a film simply gains a healthy amount of passionate respect over time; those are hardly rare, and easy enough to diagnose, as some films simply take a while to find an audience. I’m thinking of the term’s truest, deepest form, where one must put an emphasis on the word cult – a movie that inspires a feverish, ritualistic devotion among its followers, where loving the film becomes part of one’s identity, an action rather than an anecdote. Those are exceptionally rare. The Rocky Horror Picture Show is, of course, the most famous one, and deservedly so, because the ongoing phenomenon it sparked in its devotees is unlike anything else in film history. It’s easy, with such participatory cult hits, to chalk it up to the old, unhelpfully dismissive adage of “so bad it’s good,” but that would of course be missing the point entirely. Rocky Horror being a film of genuine (if weird and specific) merit, for one; the fact that no movie inspires people to dress up and attend a party of a screening every month for 40-plus years on the basis of simple mockery another. No, Rocky Horror is the definition of a cult classic because people love it to their bones, find something so unique and special inside of it that there’s no other way to express that affection except through boisterous participation, to extend the movie to part of oneself, and put part of oneself into the ongoing life of the movie. The same can be said, on a lesser scale, to something like Tommy Wiseau’s The Room, which is in every critical regard an ‘inferior’ movie, yet inspires vocal, celebratory participation because there is simply nothing else remotely like it, and the specific, oddball wavelength it operates on resonates at a frequency one cannot find in anything else.

This, truly, is what makes a film a definitional cult classic: an energy so specific, strange, and inexplicable that it commands one’s attention, tuned to a pitch high enough that a large number of people are going to be startled by it – and in being startled, they will join in, because getting a piece of whatever oddball action the film is offering is simply undeniable.

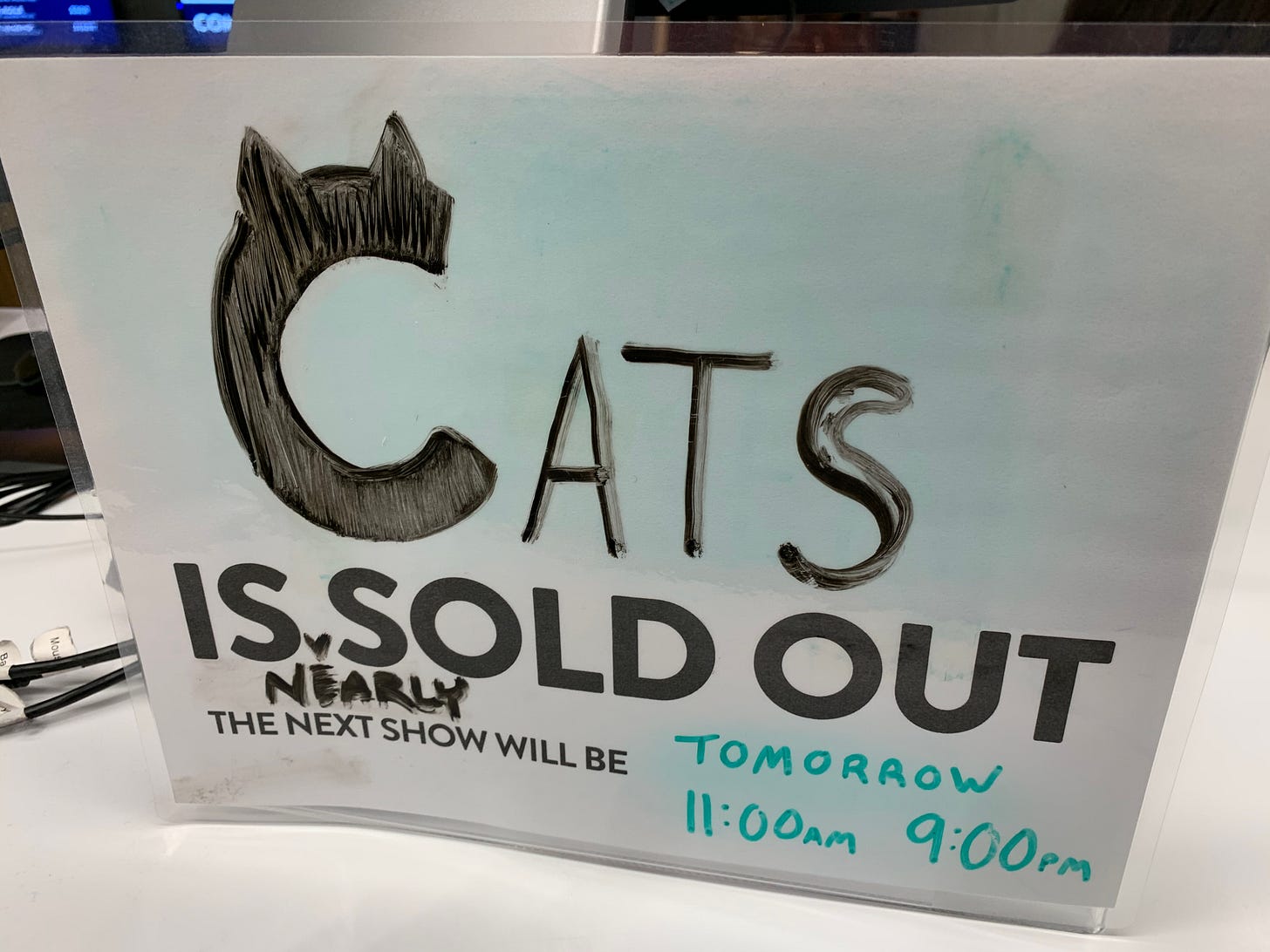

Tom Hooper’s roundly maligned adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats is that kind of film, and I know it because I felt it, and it’s an experience that cannot be faked. I missed the film entirely in its brief bomb of a theatrical run over the holidays, as I was traveling in Japan for three weeks, and when I got back, the Fandango ticketing app informed me it was not playing within 100 miles. A fortuitous let down, as it turned out, because this week, our local non-profit theater here in Iowa City, the wonderful FilmScene, played the film on a Friday night in their big new auditorium. It was clear this would be no sober cineplex crowd unaware of what they were getting themselves into; by the time I checked the ticketing site on the day of the show and realized there was only one seat remaining, I could see there was a feverish anticipation to have some fun with what has already become a legendary cinematic oddity, and I knew I would kick myself forever if I missed out.

From the moment the lights went down, and the entire room cheered just to see the intensely bizarre-looking cat people, I knew my instinct was correct. Cats is, indeed, as bonkers as every tweet, review, and GIF have told you it is, but it is also a profoundly fun communal experience, and if this small-town screening was anything to go by, it’s not hard to see the film becoming the kind of recurring movie theater party that gets people excited to go out late on a weekend to celebrate – and, of course, to drag along an uninitiated friend or two. This was, simply put, one of the most raucously fun times I’ve ever had in a movie theater, so much so that it’s almost impossible to say where the film ends and the audience begins, with laughter, applause, cheers, and calls-and-response driven as much by viewers bouncing off one another as by the insanity unfolding on screen.

Cats is truly one of a kind. There is nothing else even remotely like it. There is not a single sober filmmaking choice on display, and there’s a manic, madcap energy undergirding everything it does, like Tom Hooper is riding the film equivalent of a mechanical bull at a particularly boisterous bar and barely managing to hang on. You’ve got a seemingly endless parade of musicians and movie stars and oversized personalities leaping onto the screen in truly unsettling CGI cat costumes, against artificial backdrops that feel like they’re out of a weird dream, spitting out a bottomless list of cat puns, singing about their weird personalities and even weirder names, writhing around on all fours and lapping milk out of oversized saucers, and gyrating against one another with a wholly unrepressed sexual energy that can only be described as deeply, stupendously horny. These Cats fuck and Tom Hooper wants us to know it. He also, frankly, wants us to find it mysteriously enticing. There’s no other way to explain what Jason Derulo, Idris Elba, Taylor Swift, or Francesca Hayward are asked to do here, to understand the size of Derulo’s CGI cat bulge, the look of unrestrained lust that permeates Hayward’s face every time she looks at Mr. Mistoffelees or Munkustrap, the way Taylor Swift is introduced lankily spread out against a crescent moon prop descending from the ceiling, or the watery sheen of Elba’s dark fur, like he’s just been oiled up to go do a photoshoot for PlayCat. An entire generation of weird musical theater kids are going to discover something about their sexuality watching Cats, and God bless every single one of them for it.

But I digress. From the moment the first teaser trailer went out and horrified the world, the CG effects have formed the brunt of the conversation around Cats, and they are, indeed, a dark wonder to behold. Even with the post-release ‘patch’ the film received after its first week in theaters to correct some glaring errors, it’s abundantly clear both that the film needed more time in the oven – there are shots where it looks like the actors’ faces are sort of floating above or in front of their cat bodies, and others where the compositing is perfectly polished – and that if the VFX artists had gotten all the time and money in the world, nobody could make this ‘vision’ feel right. Cats may be the ultimate example of Hollywood busting out the CGI tech just because they could, and not in any way because they should. All the VFX artists are doing is taking what could absolutely be physical costumes, make-up, and prosthetics – much cheaper, more convincing costumes, make-up, and prosthetics – and supplanting them with expensive, ungainly CGI doppelgängers of those physical assets. They aren’t transforming the actors into literal cats, or replacing the underlying performances and physical choreography. They’re just applying the same kinds of make-up and costumes Cats has been doing on Broadway for decades, but spending untold man-hours and a cool $100 million dollars to do it, all to create an effect that is the absolute definition of uncanny valley. It looks like it could be real, should be real even, but it isn’t, often conspicuously so, and one’s jaw is left agape. It is desperately deranged, unfathomably bizarre, and must be seen to be believed – especially when one considers the litany of strange things these performers are doing under all that digital makeup.

But it’s also kind of wonderful, because when the movie starts and you’re faced with these uncanny digital cat people, you really only have two possible reactions: To recoil in terror, or laugh at the absurdity. And when combined with the weird horny energy Hooper brings to the project (or, at least, finds himself unable to contain) and the underlying ‘children’s-book-made-a-wish-on-a-cursed-monkey’s-paw’ insanity of the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, laughter feels like the most natural reaction. In a big, crowded theater, that laughter is infectious, and it only grows as it bounces off everyone else.

Hooper and co-writer Lee Hall have attempted to wrangle Webber’s feline revue of a stage-show into something slightly more focused as a two-hour film via the Francesca Hayward character, an abandoned cat taken in by the Jellicles who serves as an audience proxy (much of what would have been direct address to the audience on stage gets redirected towards her character). But, wisely, they haven’t done much more to sand it down than that – this is still, essentially, a series of character-based vignettes as a procession of cat characters comes out, does a song and dance, and then exits stage right. The plot is as thin as it gets, and while the film may have earned more traditional critical respect if it tried to make a more obvious cinematic structure out of the stage show’s pieces, it wouldn’t be anywhere near as much fun. Because it’s in that loose, openly performative style that room is left open for the audience to have fun, and it’s where the film’s strange magic comes through. At my screening, those familiar with the show cheered every time a new favorite character appeared for their big number, and the energy was positively infectious to those, like myself, who were experiencing all this for the first time. Nearly every number is a crowd-pleaser is one form or another, and some, like “The Rum Tum Tugger” or “Skimbleshanks The Railway Cat,” absolutely brought the house down. “Mr. Mistofelees,” a climactic song sequence where the magician cat tries to summon his full power, is such a full-bodied moment of theatrical participation that it’s a wonder Hooper didn’t just layer in sing-a-long subtitles for the chorus. We were all doing it by the end, and when Mr. Mistofelees’ magic finally pulls through, the applause would have been fit for a rock star entering an arena.

It seems clear to me this is no accident on the part of the filmmakers. One need look no further for proof than to the very conspicuous pause Hooper leaves at the conclusion of every musical number for audience applause. We were rowdy, and clapped hard at the climax of every song, and I cannot recall missing any dialogue, because the space is just there for the audience to fill. More importantly, the sequences are, by and large, worth the vocal adoration, whether because they are such gloriously unhinged spectacles of lunatic imagination – see “The Old Gumbie Cat,” whose terrifying mice people and grotesque anthropomorphized beetles that get bit in half by a furry Rebel Wilson will be the source of countless future night terrors – or, more frequently, because they’re displays of damn good Broadway-caliber choreography that are captured and edited, if not always expertly, then certainly with passion and gusto.

The trailers for Cats featured the name of choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler, Tony Award-winning choreographer of Hamilton, as a major selling point, and it’s no empty promise. Good, solid, imaginative musical choreography is by and large a lost art in Hollywood movie musicals, and Cats is at its best a refreshing throwback to a time when bodies moving in finely-planned patterns on a big cinematic canvas was a principal attraction of going to see a musical. That those bodies are covered in weird CGI fur doesn’t detract from the quality work the entire ensemble is doing and, if I’m being honest, adds a whole layer of surreality that only makes it more memorable. When Cats is fully cooking – and it really is, in places, like the utter bacchanal that is “The Rum Tum Tugger,” or the tap dance-fueled glee that permeates “Skimbleshanks” – it’s cooking with gasoline, and the slightly dazed fun every weird cat person appears to be having on screen translates in full force to the audience.

A major part of why Cats “works” – in the weird, specific, participatory way that it can be said to work – is because the cast is, almost to a person, so fully committed to whatever the hell is going on. With the exception of James Corden and Rebel Wilson, sticking to shtick that wasn’t particularly charming or funny when introduced to us on the other end of the decade, everyone shows up ready to play, from musicians like Derulo and Swift to dancers like Steven McRae (Skimbleshanks) to actors like Laurie Davidson (Mistoffelees). Idris Elba knows exactly what he is doing here, committing to his sexy, villainous energy with wild abandon, and Jennifer Hudson dutifully treats her big solo like she’s out of a completely different, far more respectable movie, one where she’s swinging for the fences in a big for Oscar glory. And Francesca Hayward is an inspired find, her ballet background put to good use throughout in a winning, nimble performance that could have been far more thankless in lesser hands.

Still, there are two old pros here who rise above the rest of the litter, and it’s astonishing just how completely Ian McKellan and Judi Dench come ready to play. These are two all-time great, world-class performers, professionals who wouldn’t know how to phone in a performance if one asked it of them, and the most out-of-body moments for me in the entire film were watching these two tackle some of the film’s silliest material with the exact level of commitment they’d bring to Shakespeare. McKellan’s big moment as Gus the Theatre Cat is truly lovely; it’s a genuinely touching, surprisingly affecting number, and by the end, there’s no joke to be made, no hint of irony in one’s enjoyment of the moment (well, maybe some irony – it is Sir Ian McKellan in a raggedy CGI cat suit, and he does lap milk from a saucer before coming on stage).

Dench, meanwhile, gets to wrap the whole film up by breaking the fourth wall and singing directly to the audience about how to greet a cat, a call-and-response number that includes the lyric “A cat is not a dog,” and goes to places of such glorious poetic absurdity that had I not known better, I would assume its source was Shel Silverstein and not T.S. Elliot. And like McKellan, she is fully committed, her innate warmth and dignity coming across so strongly that I must admit, dear reader, that this was the moment I lost it. When she invited us all to sing along with her that a cat is not, indeed, a dog, I collapsed into a fit of giggles so intense I nearly fell out of my seat.

Tom Hooper is, I think we can agree by now, a mostly dull and uninspired director, one whose small bag of bland tricks would be acceptable if unremarkable on television but has proven consistently disappointing on film. The biggest surprise of Cats, in all honesty, is that it feels like he’s actually having fun, mostly tossing out his limited playbook and letting the zaniness of the material come forth. When a moment calls for big, raucous energy, he delivers big, raucous energy, almost like it’s out of his control. And maybe that’s the key, because at its ‘best,’ Cats doesn’t feel like anyone is in control. It feels like a giant, unwieldy studio picture of some deeply bizarre material that no one figured out how to wrangle into something clear or manageable, and, well, that’s probably exactly what it is. Sometimes, projects go south, accidents happen, and before you know it, you’ve covered Taylor Swift in CGI cat fur and asked her to sparkle glittery catnip all over Dame Judi Dench. Even a great director would probably get lost in the shuffle. Tom Hooper isn’t a great director, and the sheer surreal insanity of the final product probably came about as a result of him getting well and truly lost amidst the madness.

The absolute worst, least enjoyable moments of Cats, in fact,are those when Hooper seems to find his footing for a second, attempting to reign it all in and make the material sober – those moments, like Hudson’s performance of “Memories,”or Hayward’s rendition of the Taylor Swift-penned “Beautiful Ghosts,” that are meant to be taken ‘seriously.’ The filmmaking here is just hopelessly inept. As he did throughout Les Miserables, Hooper directs his actors to plant on a mark, stick to it like super glue, and proceeds to film the entire thing in an uncomfortably intimate medium close up that is not in any way conducive to musical filmmaking. When those moments arrive, you can just feel the air go out of the film, the audience deflated alongside it. There is no energy, no inspiration, no sense of passion. Hudson brings enough to just barely salvage “Memories,” and a gleeful-enough audience can certainly fill in at the margins, but the point still stands: The moments when Hooper most clearly exerts directorial control are the ones in which the film is most devoid of life.

Thankfully, those moments are few and far between. Cats is insane, and it prompts a joyously lunatic reaction from an audience primed to receive it. Is the film good? Is it bad? I don’t know how I would answer that, and frankly, I don’t care. It is utterly singular, and I am entirely sure that no film able to facilitate an audience experience as celebratory as the one I enjoyed is without merit. Cats is not a movie you should watch alone at home. It’s not the kind of film you should casually rent on a lazy Saturday to see what all the fuss is about. It is a movie that absolutely must be experienced with others, ideally in a big group with a loud sound system, and it’s one that will, I predict, inspire a good deal of ongoing devotion for whom this becomes a recurring social event. Good movies and bad movies alike are a dime a dozen; we are inundated with prime examples of both. A movie like Cats, though, that isn’t so much a qualitatively coherent film as it is a delirious hallucination, best enjoyed as a collective trip? Those only come across once in a great long while. When they do, they’re magical.