Celebrating "Jurassic Park" for its 30th Anniversary on National Cinema Day

Clever girl indeed

Today was ‘National Cinema Day,’ and I observed by taking in a 30th anniversary screening of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park in 3D at my local multiplex. As always, this movie astounds me. I last wrote about the film ten years ago for the 20th anniversary, when the 3D version was first released to theaters, and I went back to that piece – originally published April 4th, 2013 for We Got This Covered – and rewrote and expanded upon it here, in an attempt to better do this great movie justice. Enjoy.

When it comes to edge-of-your-seat, deliriously entertaining adventure filmmaking, nobody does it better than Steven Spielberg, and Jurassic Park, just as wonderful today as it was in 1993, is one of the greatest testaments to this undeniable truth.

Like most children of the nineties, I was infatuated with Jurassic Park as a child. I was too young to witness its groundbreaking theatrical success, but I discovered the movie on VHS, and watched it over and over, always eager to revisit Isla Nublar for an adventure with tyrannosaurs, velociraptors, and all of the park’s other incredible inhabitants. The DVD was one of the earliest movie discs I owned, and in addition to watching the film religiously in this new format, I also devoured the special features repeatedly, entranced by the fascinating production stories of how Spielberg and company made such astonishing movie magic.

Revisiting the film today, that magic has not diminished in the slightest. From the moment the opening titles appeared, I felt like a child again, as completely enveloped by the wonder, horror, and non-stop exhilaration Jurassic Park provides as ever before. Yet viewing the film with an adult’s eyes does add new, invaluable layers to the experience, for I find it utterly mesmerizing to see all the ways Spielberg so precisely plays his audience like a fiddle. The sheer overwhelming craftsmanship of this film is as awe-inspiring to me as any of the dinosaurs on screen. No other director, alive or dead, is as good at pacing adventure films for maximum tension, awe, and satisfaction, and while I sometimes feel the instinct between viewings to rank Jurassic Park a few rungs down the ladder beneath Raiders of the Lost Ark or Jaws, I am always disabused of that notion when going back to it, because this is just as tremendous a proof point of Spielberg’s fundamental talent for speaking the language of cinema.

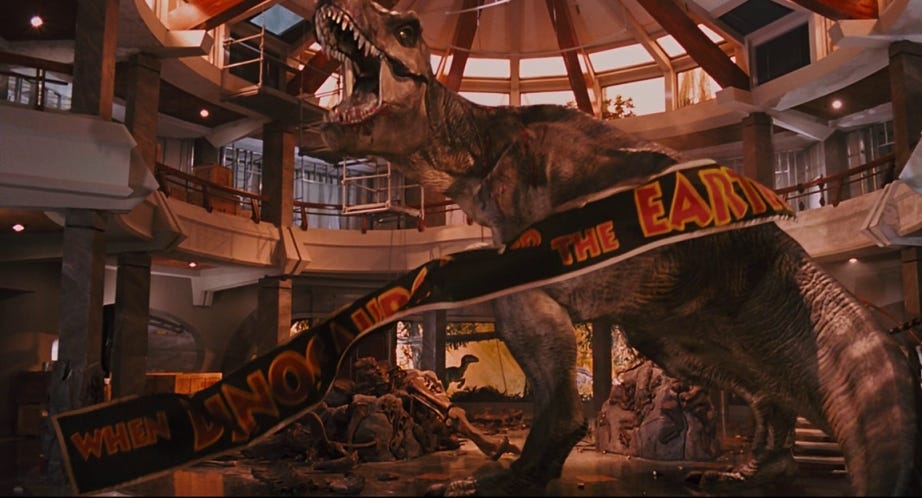

There is a giddy, borderline-sadistic quality to the way Spielberg doles out action in Jurassic Park, meticulously putting the pieces in place over the first hour – which is a slower-burn than I remembered, and all the more satisfying for it – so that when it all comes together during the iconic T-Rex reveal – still among the greatest of all cinematic set pieces – the audience is already perched perilously far along the edges of their seats. When the action does start coming, it is relentlessly intense and wildly go-for-broke, completely shameless in its attempts to excite, terrify, and thrill. This is a film I know inside and out, beat for beat, yet every time I watch it anew – especially when screened theatrically – I find myself as fully engaged as if it were the first time, leaning forward in my seat, feeling my breath slow at the tensest moment, laughing hard at the handful of perfectly executed jokes, and full-on gasping when Spielberg goes for the jugular (that moment where the velociraptor jumps at the camera as Lex jumps away at the last second gets me every time).

The human element of Jurassic Park does not approach works like E.T. or Close Encounters of the Third Kind in terms of dramatic depth, but the script is actually pretty intricate in its crisscrossing array of character arcs and motivations, which, while often fairly simple – Alan Grant thinks he doesn’t like kids and now has to protect them; John Hammond wants the wonder of Jurassic Park without acknowledging the danger, and has to get his priorities straight – are nevertheless effective in giving the adventure a sense of real human weight.

The sheer number of great characters here is easy to take for granted, but it's truly one of Spielberg's deepest ensembles, and absolutely crucial to the film’s success. Jeff Goldblum and Richard Attenborough have the two most iconic parts, and the latter in particular is the performance and characterization most important to the film’s wondrous sense of tone, but the bench here is so ridiculously deep. Sam Neill is not your average action movie leading man, and that’s exactly what works about Alan Grant – he’s a scholar and a teacher, a natural educator who connects with the children he’s paired with in the film’s second half through their mutual wonder of the natural world. Laura Dern is giving a full-on movie star performance here, radiantly charismatic and funny (“dinosaurs eat man, woman inherits the earth” still gets a big laugh in the theater, 30 years on), and the chemistry she and Neill have is something special. They’re a romantic couple, but not a ‘movie’ couple; they’re quietly comfortable with one another, and she playfully pushes him outside of his comfort zone, and he’s never threatened by Ian Malcolm’s awkward and obvious flirting. They’re actual partners, in multiple senses of the word, and the lived-in nature of that relationship does a lot to ground the reality of the film around them.

And yet I’m still just scratching the surface; the young Ariana Richards and Joseph Mazzello round out the main characters, and prove once again Spielberg’s talents for casting and directing kids, but on the periphery you’ve also got an absurdly fun Samuel L. Jackson, delivering every single line with a cigarette in his mouth; Wayne Knight at the peak of his dirtbag comedy powers; Bob Peck as warden Muldoon, telling us about raptors testing the fences and rewarding one of them with a heartfelt “clever girl” when his time comes; and B.D. Wong as the eerily grinning face of scientific overreach. The bench of talent and the sheer vibrancy of every characterization here is immense. There's a lot of cross-cutting between groups of characters in the second hour, and part of why it works so well is that Spielberg can cut to any corner of the movie and land on a great character played by an amazing actor.

The thing I love most about Jurassic Park is how deftly it situates itself at the intersection of horror and wonder. Something all the sequels to this film get wrong – especially the detestable Jurassic World trilogy, but also Joe Johnston’s Jurassic Park 3 and Spielberg’s own The Lost World – is that they tonally and structurally position themselves as monster movies, like King Kong or Godzilla, films about fantastical creatures threatening and enacting widespread destruction. But that’s not what the original Jurassic Park is. For every moment of terror, there is an equal and opposing moment of grace, of beauty and awe at the natural world and these creatures plucked out of time. Most of the dinosaurs in the film aren’t threatening at all, and there is just as much time devoted to empathizing with these creatures – like Ellie treating the sick triceratops, or Alan and the kids watching the brachiosaurus feed – as there is to running from them. The T-rex is terrifying, but it isn’t personified as evil or malicious, and it even gets the big iconic hero moment at the end. The raptors are the closest the film comes to creating outright ‘monsters,’ but even then, what’s terrifying is their intelligence and cunning, and there’s an entire character – Muldoon – who exists to pay them grudging respect. The reason the special effects – created using every available trick in the book, from CGI to animatronics, by the legendary power trio of Stan Winston, Phil Tippett, and Dennis Muren – are still so miraculous is that even if you go into the film wanting to pay attention to them, you quickly forget any of this is trickery. It all just feels real, immediate and tactile and seamless, and that’s a testament not only to the quality of the effects, but the careful and purposeful deployment of them, of the choices made in direction and cinematography and editing and performances to make it all feel like a naturalistic whole.

The beautiful John Williams score is actually fairly minimal through much of the movie, and it’s used much more in scenes devoted to appreciating the dinosaurs – like the initial encounter with the brachiosaurus – than it is in scenes of tension and horror, where the score drops out entirely. Spielberg deploys Williams less to help juice the action, a la Raiders of the Lost Ark, then to sell empathy and wonder with these non-human creatures, a la E.T. – and I think that’s absolutely crucial to understanding what a special and singular achievement this film really is.

Every single component of Jurassic Park is finely tuned and precisely calculated to produce maximum enjoyment, to deliver an all-encompassing entertainment powerhouse, and one of the greatest joys of seeing it whenever it comes back to theaters is the ability to watch the film with a crowd. Seeing Spielberg’s machinations pay off in the communal reactions an audience shares, be it a large group of people or a small one, is profoundly impressive, even having seen the film theatrically two or three times now. The film remains the best dinosaur adventure film there ever can or will be, and even thirty years after its initial release, it’s one of the single most entertaining and immaculately crafted films to play in theaters this year.

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our sister series about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Explore our archives and subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all podcasting platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com