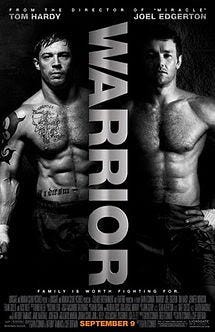

Early Review: "Warrior" is a unique, blindingly brilliant fighting drama

Film Rating: A

In the opening sequence of Gavin O’Connor’s mixed martial arts drama “Warrior,” former boxer Paddy Conlon (Nick Nolte) is found driving through the streets of his native Pittsburgh, listening to Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” on tape. The audiobook resurfaces as a key motif throughout the film, gradually revealing itself as a commentary on the lives of our protagonists, Paddy and his sons Brendan and Tommy. Like Captain Ahab, all have experienced significant trauma in their pasts and have a goal in mind to reclaim their destinies. The men of the Conlon family are single-mindedly obsessed with achieving their goals despite knowing full well the kinds of emotional and physical pain they will receive in the process – and even after experiencing the deepest fathoms of this pain, they continue to move forward.

“Warrior” embraces that pain on every level, delivering heart-wrenching, honest performances, uncompromisingly brutal fight choreography, and a story more interested in critiquing and dissecting the art of the fight than embracing it as a means to inspire the audience. It plays by genre conventions while knocking them down flat, and for every punch it dishes out to the characters, it sends another equally brutal one straight through the viewers’ heart, on and off the ring. Simply put, “Warrior” is one of the most unique, raw, and emotionally devastating sports dramas I’ve ever seen, and of the best films to hit theatres this year. Continue reading after the jump...

The Conlon family has a rich and troubled backstory that O’Connor wisely never feels compelled to directly explain to the audience; instead, we pick it up through the characters’ naturalistic interactions. Father Paddy’s alcoholism tore his family apart many years ago; sons Brendan (Joel Edgerton) and Tommy (Tom Hardy) haven’t seen each other or their father much in the last decade and a half, if at all, but circumstances compel them to reunite. Tommy seeks out his father not for reconciliation, but to be his new trainer; a former Marine and a talented fighter in high-school, Tommy is intent on participating in a dangerous, high-stakes mixed-martial-arts competition, ‘Sparta,’ where the winner will walk away with five million dollars. As the film’s most closeted character, Tommy’s motivations aren’t immediately clear, but Paddy’s are simple: 1000 days sober and full of remorse, Paddy is enthusiastic for any chance to do right by his son.

As for Brendan, he’s led the most successful and healthy life; he has a wonderful wife, Tess (Jennifer Morrison), two beautiful daughters, and a career teaching high-school physics. But even Brendan’s landed on hard-times; even though he and his wife work extra jobs, they can’t pay the increasingly high rates on their mortgage, and are three months away from foreclosure. Before becoming a teacher, Brendan had minor success as a fighter in the UFC, and in the midst of his financial troubles, sees fighting as the best way to provide for his family.

As I said above, all three men in the Conlon family enter into things knowing that pain will be involved. For Brendan, that pain is quite literal; not only is he getting savagely beaten to provide for his family, but he has to subject his loving wife to the sight of his battered face and the constant threat of more serious injuries. Tommy is tougher, but he also has more to lose: he deserted the Marines, and while I won’t spoil what he needs $5 million for, it’s motivation enough for him to risk imprisonment; Tommy is certainly smart enough to know that the media attention he’ll get during the tournament will inevitably lead to his discovery by the authorities. Paddy isn’t going to get beaten up or thrown in jail, but he knows his kids detest him, and if he wishes to set things right, he’ll have to relive the darkest parts of his past and stare down the lifelong pain and disappointment he planted in his children.

Even in the best case scenario, none of these men are going to walk away from the fighting unscathed, both emotionally and physically. Personally, I was most strongly affected by the emotional beat-downs the film doles out, so thoughtful and precise is the material. The history of the Conlon family is simply heartbreaking to learn about, and I love how the backstory is parsed gradually throughout the picture, coming across only in moments when it feels natural for the characters to discuss their pasts. Even then, the audience is asked to piece a lot of things together, and as we do so, we learn about these wonderful, scarred characters and their broken relationships. Nick Nolte’s performance gives the family drama its heart, constantly leaving the viewer breathless or on the verge of tears; he packs a lifetime of pain and regret into every bit of dialogue or facial expression. We sympathize for this man while understanding why his sons rightfully hate him.

That’s not to say Joel Edgerton or Tom Hardy get lost in Nolte’s shadow. Of all the characters, it takes the longest for us to really understand Tommy, but Hardy presents this damaged, tortured soul as a fully realized, three-dimensional creation from moment one. The script leaves most of Tommy’s characterization in Hardy’s hands, and if he wasn’t up to the task, the entire film would fall apart; instead, we are mystified by Tommy’s struggles, and we root for him just as strongly as his brother, who is clearly the more conventional hero. In a film like “Warrior,” though, conventional still means compelling, and even though Edgerton’s Brendan is the most stable of the three leads, I was most enthralled by his performance. There’s something fascinating about a man surrounded by so much love, from his wife and his kids, who is still in so much pain, and Edgerton hits this role out of the park, completing a trio of three brilliant, heart-wrenching lead performances that define what “Warrior” is all about.

Brendan’s story highlights an additional avenue of emotionally charged content: his relationship with his wife and the struggles of working-class Americans. The first act presents a very powerful, naturalistic portrait of a family in tough economic times, and once Brendan decides to solve their financial woes by fighting, we get a brilliant take on the old sports-movie cliché of the worried wife. Tess understandably doesn’t want her husband fighting, and though she’s swayed a bit too easily in the last act, overall, “Warrior” does an outstanding job turning this cliché into something complex and emotionally palpable, thanks in no small part to Jennifer Morrison’s wonderful performance. I’ve always appreciated her work, but here, she demonstrates that she is far more talented than past roles on TV shows like “House, M.D.” have suggested.

Tess’ fears about Brendan’s fighting are treated seriously, and this leads us to one of the film’s most poignant and effective arguments: that fighting is dirty business. We’re accustomed to sports dramas uplifting or inspiring us, but “Warrior” isn’t interested in any of that. Fighting is a symbol of the lives the Conlon brothers have tried to leave behind, but desperate times have led them back into the ring as a last resort. While there is some catharsis in Tommy and Brendan’s fighting, for the most part, they are here because life has given them no other options, and the beat-downs they dish out and receive are not something to be proud of. Indeed, the way these men use and abuse their bodies for money drew parallels in my mind to prostitution. The difference between prostitution and fighting, of course, is that fighting-based sports are celebrated in our media, and “Warrior” even uses the genre convention of ESPN narrators to highlight what an exploitative, overpowering, and uncomfortable nature the media adds to these fights. No matter what your opinion on MMA going into the movie, I’m sure you will be shaken on your way out.

I said earlier that the emotional material engaged me more than the physical, but that’s only by virtue of the story; on a technical level, these fights are amazing feats of choreography – realistic, brutal, and unflinching. Masanobu Takayanagi’s cinematography captures it all marvelously, using the wide 2.35:1 frame in a very unconventional way; rather than using that extra widescreen space for breathing room, as is more common, he crowds each frame to the point of discomfort. It’s compellingly raw and engaging during simple shots such as conversations, but the full brilliance of the technique really comes to the forefront during the fights, where the framing forces the viewer to confront the brutality of each match in a visceral manner.

I’ve discussed the film’s physical and emotional aspects separately, but “Warrior” only succeeds because it combines the two beautifully, sending the viewer into each match with a clear understanding of the cast’s motivations. That gives real weight to each fight; a few of the early brawls go on too long, but for the most part, the fights are seamlessly integrated into the drama, essential components of the story. It all culminates in the climactic brawl, where Tommy and Brendan go head to head for the championship. This is “Warrior” at its most original, a sports drama where there is no clear hero in the final confrontation; Brendan and Tommy both have earned their way to this match, and as the viewer, we have no idea who to root for. It’s unsettling, but brilliant, and the drama in this final match is as compelling as any conversation found in the rest of the film. O’Connor took a huge risk resolving the story with almost no dialogue in the ring, but that risk pays off in spades; I won’t spoil the ending, but it involves two sentences and the most emotionally charged pat on the back I’ve ever seen, one that will drive you to tears unless your heart is made of stone.

One thing I will say is that the ending doesn’t resolve everything with a nice pretty bow on top; only one character really comes out of the story in a better place than where they started, and they still took a massive beating to get there. I respect the film immensely for this; the typical Hollywood ending would be blindingly uplifting, but “Warrior” strives for something more special: a fulfilling ending.

Then again, your interpretation of the film may vary wildly from mine. That’s true of all movies, of course, but I feel it’s especially important to note here. “Warrior” is so rich and dense and brutal and beautiful that any two viewers will inevitably walk away with at least a slightly different impression, which is the mark of a great movie. And make no mistake, “Warrior” is great. All the leads deserve recognition come Oscar time, as does the film itself; it’s one of the year’s best, and I strongly urge readers to give it a chance when it hits screens this Friday.