Essay Day – "Aggression and the Modern Pathology in Polanski’s 'Knife in the Water' and Kieslowski’s 'A Short Film About Killing'"

It’s Wednesday, which means it’s time for the penultimate ‘Essay Day’ here at Fade to Lack. As explained here, I have written a large number of essays during my time at the University of Colorado as a student in film studies, and I thought it time to share the best of those with my readers, so throughout the summer, I have been posting a new essay every Wednesday, all focused on film in one form or another, but often incorporating other research and fields of study. This is the second to last installment, and the series will be concluding next week.

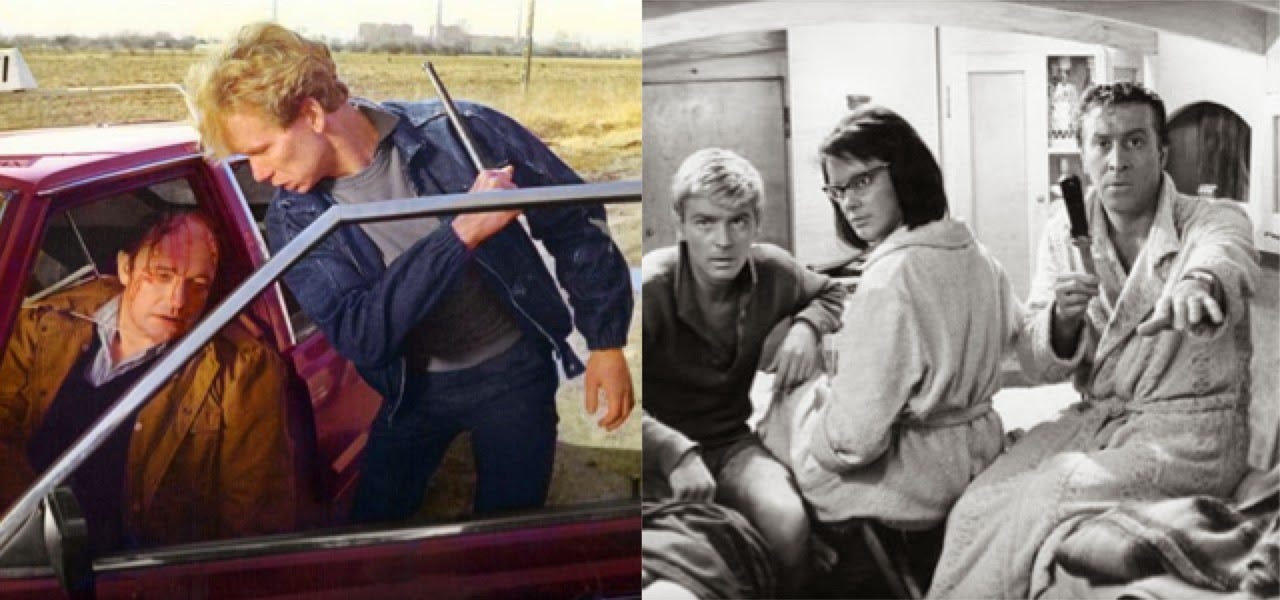

This week’s piece was one of the several in this series never written with publication in mind, as it was penned for an in-class exam in just one hour. But I find the films discussed here very interesting, and the ideas explored worth sharing, so I felt the essay would be of interest to readers. The course was called ‘Cinema and the Poetics of Transgression,’ exploring issues of transgressive behavior in a variety of foreign feature films, and the essay prompt was to use two films viewed in class – specifically, Roman Polanski’s 1962 film Knife in the Water and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s 1988 film A Short Film About Killing – and discuss how aggression is represented and explored in each. As this was written for an exam in a classroom setting, there is less of the usual shorthand plot synopsis for those who have not seen the films, so you may wish to seek them out before reading. Otherwise, enjoy...

Read “Aggression and the Modern Pathology in Polanski’s Knife in the Water and Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Killing” after the jump...

Like all human emotions, aggression is as elusive as it is pervasive. Impossible to fully understand, and rooted in a variety of similarly enigmatic human urges and flaws, aggression is something we are at once familiar with and intellectually detached from, a notion that is at the heart of both Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Killing. While both films try, in part, to understand the sources and contexts of aggression in intellectual, ordered ways, they are ultimately studies of the mysterious emotional state that is aggression itself, of the universal human struggles and shortcomings that drive us to feel aggressive, and of the instinctual, senseless forms violence takes when stemming from such dense and complicated emotional issues.

In analyzing the sources of aggression, both films tackle their subject from two directions: First, as a study of the modern, societal concerns that lead to aggression (the sources of a modern pathology, one might say), and second, as an exploration of the basic, more universal human instincts and traumas that lead one down an aggressive path. On the former, both films are intensely aware of the society in which these characters exist. That society is depicted clearly in A Short Film About Killing, as the film’s first half follows each of the three main characters – Jacek, Piotr, and Waldemar – as they go through a relatively normal day in and around the city in which they live, while society is a much less immediate force in Knife in the Water, which takes place entirely removed from cities, social centers, and even other people.

Nevertheless, the influence of the modern society Andrzej, Christine, and the Hitchhiker – the film’s only three characters, confined on a boat together for most of the run time – come from is felt throughout, most notably in the concept of materiality. Upper-class, middle-aged Andrzej clings tightly to his yacht, his pride and joy and central symbol of bourgeois decadence and power, while the Hitchhiker, although assumedly hailing from a ‘lower’ social class, is similarly attached to the knife of the film’s title. The obsession over materiality and material pride – a modern, socially-ingrained pathological issue – is a major part of what brings the characters to blows later on, and is of course fundamental to their aggressive instincts. The same can be said of Jacek, the killer, and Waldemar, the cab driver (and victim) in A Short Film About Killing. Waldemar is as in love with his cab as Andrzej is with his boat, and even prioritizes it above other people, as witnessed in the scene in which he denies service to a couple so he can continue cleaning and fawning over his vehicle (an obviously aggressive action, which stems, again, from material pride). While the film leaves Jacek’s motives for killing Waldemar at least partially ambiguous, the fact that Jacek, after murdering the man, takes the beloved car – and believes it will impress and endear him to the young woman he fancies – is again indicative of a modern aggressive pathology stemming from modern materialistic obsession.

The other obvious societal contribution to the characters’ aggression is repression – a clear-cut case of bourgeois repression for Andrzej, and a more general lack of emotional communication skills for characters like the Hitchhiker and Jacek. All these characters have aggressive instincts and urges, but because of their own emotional repression, finding a healthy outlet in which to explore them is impossible. As Jacek’s wanderings in the first half of Killing clearly show, he is searching for, and is continually unable to find, an outlet for his violent feelings in a society which ignores or has no place for emotionally turbulent behavior. We can assume he has been ‘searching’ in this way for a long while, in this and other cities and social centers, and that at the time we meet him, this aggression has been repressed, unable to be healthily explored or treated, for some time. Similarly, Andrzej is also a very troubled person, someone who we can fairly assume is unhappy or unfulfilled in life, and whose aggressive urges he channels into his sailboat, into his material goods, and into showing off for other people. Finally, the Hitchhiker, by removing himself from society, is a fairly laid-back, healthy person when we meet him; by freeing himself from social strata, he has largely purged himself of aggression. Coming back into contact with a context of social repression – personified by Andrzej and, to a lesser extent, Christine – brings out aggression that had been dormant.

In these ways, we see that society and socially ingrained aggressions are, in both cases, partially responsible for the creation and perpetuation of the modern pathology that leads to the films’ aggressive consummations. But social analytics only take us so far, and do not clearly explain all aspects of aggression. A less intellectual, less clearly ordered approach must also be taken to understanding this complex human emotion, and that is what Polanski and Kieslowski give us in exploring, respectively, the sexual urges that propel Andrzej’s and the Hitchhiker’s aggression, and the traumatic anguish that fuels Jacek’s own isolation and anti-social behavior.

On the first point, the sexual ‘contest’ between Andrzej and the Hitchhiker over Christine is clearly the most significant source of aggression in the film. It is also one of the ideas that, as much time as the film spends exploring and depicting it, is hardest to nail down or explain in a reasoned, ordered fashion. Why does Andrzej need to feel so threatened by the Hitchhiker as to become outright aggressive? There are explanations, of course – the Hitchhiker’s youth and virility, Andrzej’s materialistic possessive behavior towards his wife, etc. – but none of them completely summarize the issue. There is something highly emotional, and highly animalistic, about Andrzej’s feeling of sexual threat, and it is something we cannot completely understand. The same goes for the Hitchhiker on the other side of the equation. Why does he feel he needs to compete for this woman? Such an urge obviously exists outside of social boundaries – she is married (a social contract), so if society were the only factor here, he would theoretically be able to repress his urges – or of reason, but he competes with Andrzej nevertheless. Oftentimes – during the games they play, or during their time on deck together – it does not even seem the Hitchhiker is fully conscious of this sexual competition. Yet he engages in it nevertheless, as does Andrzej, and we may conclude that sexuality – a universal human urge that exists with or without society and social pressures – and, in turn, other universal human emotions are as fundamental towards aggressive states as the aforementioned social factors.

We may say a similar thing for Jacek, though Kieslowski is even more interested in the non-definable emotional issues that contribute to transgression than Polanski is. We learn, at the end of the film, that there was trauma in Jacek’s past involving his sister, but Kieslowski does not tell us exactly how this trauma affected Jacek, nor how the trauma contributed to his violent actions. We may make assumptions, watching how Jacek moves through the world and commits murder, that trauma – which, like sexuality, is a universal human struggle that does not need society to exist – has as much or more to do with his anti-social actions as the ‘modern pathology’ of society and social repression does. Again, there is an indefinable emotional element to Jacek’s aggressive tendencies, and that tells us something about how aggression is, in and of itself, indefinable.

Both filmmakers pinpoint isolation as the core context in which aggressive states perpetuate and are acted upon. Polanski’s isolation is literal, as his three main characters – the only three characters – spend the film alone on a ship, in the middle of a lake, disconnected from the world around them (even if they continue to be marked by it). It is only in this geographical isolation that Andrzej and the Hitchhiker allow their aggression to come out in full, and it is telling that once Andrzej returns to land, and becomes ‘un-isolated,’ he comes to his senses and feels moral shame for his aggressive actions. Kieslowski’s isolation is more figurative, though it is certainly important to note that Jacek commits his murder in a very remote area (and that the State, in carrying out Jacek’s execution, performers its own murder in a hidden, isolated room). Kieslowski is more concerned with emotional isolation, studying, for much of the film’s first-half, how closed off Jacek seems to be from the world around him, how he cannot communicate with others and resorts to violence and aggression in a variety of cases (scattering the pigeons, kicking the man in the bathroom, etc.). Isolation can, therefore, exist as an emotional state as well as a geographical one, and both films argue that it is when people find themselves in isolated states that their internal aggression comes forth.

This leads us to the depiction of violence, which both films illustrate to be simultaneously instinctual and senseless. The major moment of violence in Knife in the Water is the on-deck scuffle between Andrzej and the Hitchhiker, in which a film’s worth of tension erupts in a brief but senseless physical struggle between the two, ending with Andrzej sending the Hitchhiker (who has said, erroneously as it turns out, that he cannot swim) falling into the water. The struggle is shot and edited in a hectic, jumbled sort of way, with faster cuts and less coherent angles than the rest of the film, creating a disorienting state for the viewer. This reflects the underlying emotions of the scene. Neither men’s actions make any amount of literal sense, nor do they seem to be deeply thought out or pre-planned. They each act on instinct, their actions revealing those instincts to be aggressive, and as there is no real ‘reason’ or ‘logic’ to their tussle, the word ‘senseless’ also applies.

Jacek’s murder of Waldemar, meanwhile, is a bit more pre-meditated, as Jacek waits for the cab driver to take him far into the countryside, and even knows how he plans to murder the man, but there is still a similar sense of disorientated, instinctual fervor to the murder. This feeling only increases as the scene moves along, and Jacek is forced to improvise to complete his crime, while Kieslowski’s cinematography – heavy on sickeningly greenish/yellow filters, and emphasizing empty space and desolation where possible – helps to suggest a conflicted and confused internal state. And there is, of course, no sense whatsoever to what he does – it is a thoroughly pointless crime, whether Jacek then steals the car or not.

In the end, both films depict violence as a sort of heated and senseless emotional state, a fervor or reverie that cannot fully be understood, and that exists because instincts take over when isolation permeates one’s internal and external settings. This is reflective of both films’ attitude towards aggression itself. Rather than something that can be coldly, academically studied, boiled down to a simple set of ideas and social problems, Knife in the Water and A Short Film About Killing go deeper, exploring aggression as an emotion and recognizing that, as with all human feelings and urges, we can only begin to ‘understand’ aggression once we accept, recognize, and take seriously its most perplexing and unknowable qualities.

Read All ‘Essay Day’ Entries Here:

#1 – Heart of the Tramp: Charlie Chaplin’s Ethic of Dignity

#2 – Absolute Contingencies: The Double Life of Veronique, Under the Skin, Proteus, and the Wonder of Internalizing Art

#3 - Louis Malle’s Damage, Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, and the Circularity of Transgressive Energy

#4 – Fire Trails on Silver Nights: Representing Wonder and Balance in Three Works by Luis Buñuel, Bruce Springsteen & Steven Millhauser

#5 – Bond on Bond: Quantum of Solace and the Elusive Case of the Bondian Ideal

#6 – Is Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan Documentary Not?

#7 – Realism and Character Study in Agnes Varda’s Cleo From 5 to 7

#8 – Maya Deren in 3D! Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, and Cinematic Visions from the Beyond

#9 – Suffering and Transcendence in Federico Fellini’s La Strada and The Dardenne Brothers’ L’Enfant

#10 – Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back, and the Reflexivity of Direction

#11 – From Book to Cinema: Adaptation and the Construction of Film Noir in The Postman Always Rings Twice

#12 – Hana-bi, Battle Royale, and a Theory of Transgressive Transcendence

Jonathan R. Lack has been writing film and television criticism for ten years, for publications such as The Denver Post’s ‘YourHub’ and the entertainment website We Got This Covered, and is the host of The Weekly Stuff Podcast with Jonathan Lack and Sean Chapman. His first book – Fade to Lack: A Critic’s Journey Through the World of Modern Film – is now available in Paperback and on Kindle. Follow him on Twitter @JonathanLack.