Essay Day - "Fire Trails on Silver Nights: Representing Wonder and Balance in Three Works by Luis Buñuel, Bruce Springsteen & Steven Millhauser"

It’s Wednesday, which means it’s time for ‘Essay Day’ here at Fade to Lack. As explained here, I have written a large number of essays during my time at the University of Colorado as a student in film studies, and I thought it time to share the best of those with my readers, so throughout the summer, I’ll be posting a new essay every Wednesday, all focused on film in one form or another, but often incorporating other research and fields of study.

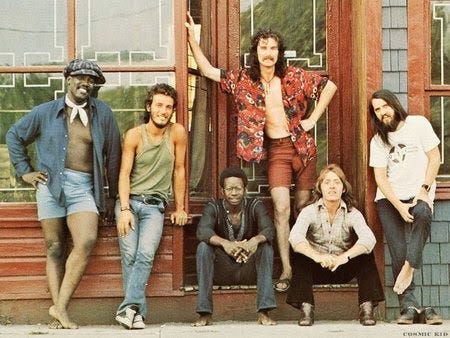

This week’s selection was written for a Graduate seminar on “Magic, Wonder, & Cinema,” taught in the Spring of 2014. The class dealt with representations of wonder in film and in writing, and the assignment of this essay was to take two specific works shown/read in class – Stephen Millhauser’s short story “The Barnum Museum” and Luis Buñuel’s feature film The Exterminating Angel – and, picking a third work in any artistic medium that explored similar themes, write about how wonder is explored or represented in all three works. I chose Bruce Springsteen’s 1973 album The Wild, The Innocent, & The E-Street Shuffle as my third work, because...well, you know me, and this is what resulted. It is one of my favorite essays in this series.

Read “Fire Trails on Silver Nights” after the jump...

Among the festive rooms and halls of the Barnum Museum ... we come now and then to a different kind of room. In it we may find old paint cans and oilcans, a green-stained gardening glove in a battered pail, a rusty bicycle against one wall ... These rooms appear to be errors or oversights, perhaps proper rooms awaiting renovation and slowly filling with the discarded possessions of museum personnel, but in time we come to see in them a deeper meaning. The Barnum Museum is a realm of wonders, but do we not need a rest from wonder? The plain rooms scattered through the museum release us from the oppression of astonishment ... These everyday images, when we come upon them suddenly among the marvels of the Barnum Museum, startle us with their strangeness before settling to rest. In this sense the plain rooms do not interrupt the halls of wonder; they themselves are those halls. (Millhauser, 84-5)

In this most important and provocative excerpt from The Barnum Museum, Steven Millhauser asks whether it is possible for the wondrous to become mundane, for us to be so inundated with wonder that its power over us is lost. Wonder dwindles, R.W. Hepburn reminds us, when “its object becomes assimilated and commonplace” – or as Millhauser puts it, when astonishment becomes oppressive (Hepburn 132; Millhauser 84). To be sustainably meaningful, wonder must have some observable or experiential benchmark against which we gauge it, and by suggesting that this benchmark lies in the mundane, Millhauser assigns inherent critical value to that which we perceive as unimportant. The ordinary has a place in the experience of the extraordinary, and visa versa – one cannot exist without the other, suggesting that a life spent solely amidst the wondrous, without experiencing the mundane, would quickly grow unfulfilling, as would a life consumed by mundanity without thought to the wondrous.

This dilemma is central to The Barnum Museum, whose unidentified narrator is sure of his obsession with the place, and sure of its personal significance to him, but ultimately uncertain as to whether or not this wonder can sustain him – whether it is “enough,” or merely “almost enough” (91). So too does this issue arise in Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, in which a collection of bourgeoisie, so conditioned to their opulence and social rituals that life for them is rigidly mundane, are exposed to a situation of dark and inscrutable wonder, one that shall either recalibrate or destroy their imbalanced lives. Balance – between wonder and mundanity, stagnation and momentum – exists most clearly for the characters of Bruce Springsteen’s The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle, who appreciate the wonder of the spaces of their youth – the New Jersey Boardwalk and its many encompassing marvels – but also insist on moving forward, changing, continuing, fighting, struggling for something new – because letting one’s existence become stale, whether in a context of wonder or a context of mundanity (which can eventually blur as interchangeable), ultimately robs that existence of wonder, and, in turn, the drive to truly live.

For Millhauser, Springsteen, and Buñuel, wonder is illustrated and characterized similarly. Millhauser’s prose, from the very first sentence, is positively dense with detail, rich in imagery and almost overwhelmingly opulent in its evocation of the museum’s grand interior.

The Romanesque and Gothic entranceways, the paired sphinxes and griffins, the gilded onion domes, the corbeled turrets and mansarded towers, the octagonal cupolas, the crestings and crenellations, all these compose an elusive design that seems calculated to lead the eye restlessly from point to point without permitting it to take in the whole. (73)

With prose as elegantly lavish as this, it takes no great feat of imagination for the reader to put himself or herself in the shoes of Millhauser’s narrator; Millhauser’s complex, rhythmic, descriptively weaving sentences do this for us. Bruce Springsteen employs a similar strategy on The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle1, offering up a barrage of mind-bogglingly dense, vividly imaginative lyrics in each and every song. Rolling Stone critic Ken Emerson famously described Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, as sounding “like ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ played at 78,” with each “five-minute track bursting with more words than this review.” The description is equally valid for The Wild & The Innocent, Springsteen’s second effort, but one of Springsteen’s major innovations here – and one which is important to consider when analyzing how he aesthetically illustrates wonder – is how fantastically alive, varied, and musically illustrative the as-yet unnamed E Street Band sounds underneath this thick lyrical poetry. Consider this verse from the opening track, “The E Street Shuffle:”

Sparks fly on E Street when the boy prophets walk it handsome and hot

All the little girls’ souls go weak when the man-child gives them a double shot

Them schoolboy pops pull out all the stops on a Friday night

The teenage tramps in skintight pants do the E Street dance and everything’s all right

Well the kids down there are either dancing or hooked up in a scuffle

Dressed in snakeskin suits packed with Detroit muscle

They’re doin’ the E Street Shuffle

If the lyrics themselves aren’t enough to make the listener viscerally feel the place, scenario, and character types Springsteen describes, the music – a killer rhythm section (consisting of Gary Tallent’s bass, Vini Lopez’s drums, and Clarence Clemons’ cool, smooth saxophone) giving pulse to the dancing, as Springsteen himself boogies across the strings of his guitar with mad improvisational fervor – is more than enough to place one’s imagination right in the heart of a rollicking, impromptu New Jersey Boardwalk street dance party. Like visiting Millhauser’s Museum, it is a situation that, if experienced, would be wondrous for a number of reasons, but our aesthetic experience of the evocation is awe-inspiring in and of itself. Millhauser uses his tools – words and their specific arrangement – to fill us with awe, to stimulate the effects of being in such an inconceivably magnificent place, just as Springsteen employs his – words and music, in perfect harmony with one another – to make us feel the wonder he sings about. Describing wonder is one thing. Doing so while simultaneously igniting the senses of the reader or listener is another, and it is essential in creating a palpable aesthetic foundation for further exploration of wonder to expand upon.

Luis Buñuel was no stranger to this idea either, and a similar effect is leveled in the visual opulence and compositional precision of The Exterminating Angel, the imagery for which was clearly so foundationally crucial that Buñuel’s original screenplay is filled with long, detailed descriptions like this:

Inside the mansion, this small room connects via a large glass door to the large drawing room. Inset in the wall to the left we see an immense cabinet with three sections, each one with a door. Each panel is splendidly wrought with bas-reliefs representing amorous pastoral scenes. They frame the doors, made of solid oak with twisting columns; on top of the frames are delicately carved leaf patterns, complex and intertwining. This great cabinet extends from floor to ceiling, from one end of the wall to the other. (Buñuel 9)

Buñuel spends another full paragraph describing this incredible cabinet and its function in the action, and though it does not appear in the finished film – the waiter who sets the table at the film’s start was to withdraw the candelabras from the depths of this cabinet – the verbal imagery speaks volumes about the visual thought put into each and every shot, and recalls the density of language in Millhauser and Springsteen. Words, however, are not Buñuel’s primary form of communication – this is a film, and when translated to screen, we are given a succession of images simply bursting with detail, captured in deep-focus, extending around the edges of the frame and deep into the background. Chandeliers, fancy chairs, gorgeous lamps, lavish drapes, painted vases, lovely paintings, and so much more litter every carefully composed image of this endlessly elaborate mansion. Like Springsteen and Millhauser, Buñuel aesthetically represents wonder through descriptive volume – there is no one image or object to wonder at, but many – and as with those artists, it is the immersive and immediate way in which he arranges and represents this extravagance which makes the viewer truly feel the degree of wonder in the setting (and which invariably draws our attention to how utterly desensitized the bourgeois characters seem to the opulent wonder around them).

Thus, for all three artists, the aesthetics of wonder are inherently tied to a certain volume of sensory input, and the way that sensory input is conveyed – through words, sound, or imagery – is crucial to creating a certain context in which wonder can exist. That context evolves over time in all three works, growing increasingly dark in The Barnum Museum (and giving way to more and more philosophical musings on the meaning of the place), increasingly surreal and indescribable in The Wild & The Innocent (until the final track, “New York City Serenade,” kicks off with a 90-second piano solo and continues into another long instrumental interlude before introducing lyrics that are highly visual but impossible to pin precise meaning to), and increasingly non-visual in The Exterminating Angel (as the plight of the trapped bourgeois continues, the amount of wonder one can perceive with one’s eyes continually gives way to the unknowable forces that compel these people to stay in the music room). But no matter how the context evolves, the level of audience immersion does not; Millhauser, Springsteen, and Buñuel show as much or more than they tell, and in experiencing the art, we become a critical part of the representations and explorations of wonder on display.

This seems fitting, as one of the two key conditions of wonder identified in all three works is a strong communal element. Millhauser opens The Barnum Museum by specifying that the place exists in “the heart of our city,” creating an immediate sense of community and indicating the Museum’s centrality to that community. He almost always uses the plural pronouns “we” or “our” in lieu of the singular “I” or “my,” even though the story is narrated from a specific, individual perspective, and while the narrator offers his own thoughts on things, he is also perceptive to the experiences of others, such as in the account of Museum-lover Hannah Goodwin (82). The Museum (and, by extension, the wonder it represents) is never experienced individually, but always as a communal venture.

For Springsteen, community is everything. It is a theme that extends across every album of his career – June Skinner Sawyers identifies the darkness of his seminal 1982 masterpiece Nebraska as arising from “a lack of community,” exploring “what happens to these characters ... when their entire social network disappears” – and The Wild & The Innocent is the record that solidifies Springsteen’s belief in the power of human relationships (33). No character exists in isolation on The Wild & The Innocent; from the street kids of “E Street Shuffle” to the tight-knit freak-show community in “Wild Billy’s Circus Story,” to the singer of “Rosalita,” who needs Rosie by his side if they are ever to bust out of their hometown status quo, Springsteen’s characters are defined by the friends they have, the lovers they long for, and the relationships they need to be empowered. Wonder is not – cannot – be experienced in isolation on a Springsteen record, especially not The Wild & The Innocent. Our communities have our back when a piece of us goes missing (“Kitty’s Back”), individuals can help to save us when we cannot save ourselves (‘Puerto Rican Jane’ to ‘Spanish Johnny’ on “Incident on 57th Street”), and a new, wondrous atmosphere is best appreciated with another by our side (“4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)”).

Community is, in some ways, more of a curse than a gift in The Exterminating Angel, but here too do we see people experiencing wonder in groups. Not just when it comes to the central set of trapped bourgeois characters, either – the plight of those trapped in the music room attracts many people from the outside to come wait and observe at the gates. Like moths to a flame, they are drawn instinctually to wonder (which, of course, is part of Buñuel’s social criticism). These interludes to the outside world are reminiscent of the passage in The Barnum Museum where Millhauser asserts “It is probable that at some moment between birth and death, every inhabitant of our city will enter the Barnum Museum,” and that at one point, the entire “city will be deserted” (80). If such a massive, attention-grabbing center of wonder exists, all shall inevitably flock to it, the wonder becoming an essential, all-encompassing communal experience. The point being, in all three works, that wonder never touches us individually – we live in and among communities, and what affects us on such a profound level is bound to affect others. Springsteen’s characters are rather well-adjusted to this truth (writing from a perspective of warm nostalgia, he had yet to introduce true darkness into his work), Millhauser’s a little more disunited and argumentative (note the many apparent controversies over the Museum the narrator informs us of), and Buñuel’s positively allergic to have to live with and depend upon one another for extended periods of time (infighting, suicides, and suggestions of ritual sacrifice stem rather horrifyingly organically from the situation). Whether the utopian nostalgia of The Wild & The Innocent is realistically feasible is a topic for another day, but for the first of several times in the course of this analysis, we see that Springsteen’s point-of-view is the most ideal. Embracing wonder together, and striving to experience and celebrate it with others, leads to happiness far more successfully than fighting back at wonder individually or in factions.

Concepts of community lie also in the connection to the circus, which recurs, overtly or subliminally, in all three works. Springsteen offers “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” – a light, tuba- and accordion-driven romp through a travelling circus, describing the backstage and in-show personalities of the many various performers – right in the middle of the album as an extended illustration of what an isolated community looks like, and for a record so highly preoccupied with the wonder of urban life and adolescent experience, using a circus as this example seems fitting. Again, there is an obvious idealization to this community – people help each other out, like when the “strong man Sampson lifts the midget Little Tiny Tim way up on his shoulders” to escort Tim back to his trailer – which speaks to the importance Springsteen places on finding like-minded people to share the world with, something the circus, in its perfect form, offers to outcasts and freaks.

In that way, The Barnum Museum is a sort of circus in and of itself, attracting outcasts (like the eerily obsessed “eremites”), grieving people trying to make sense of the world (the aforementioned Hannah Goodwin), and individuals like the narrator and his companions, who frequent the Museum because it helps them make sense of the world outside (88, 82, 89-90). P.T. Barnum’s real-life connection to the circus aside, Millhauser’s vision of the Barnum Museum is, functionally, a circus, filled with so many attractions that one does not know where to look, and which brings people together who otherwise might not have a place in the world. Buñuel too hints at a symbolic circus, bringing the term to mind when we learn the Nobile mansion is filled with lambs and even a small, highly trained bear, creatures that raise association with the circus (petting zoos and trained animal performers), and underline an implicit connection between literal circuses (organized shows of prepackaged wonder performed for the public) and bourgeois social gatherings (the same thing, in essence). When one factors in the religious dimension of the film (more on that in a bit), the implications of a possible circus connection in Buñuel’s social critique become all the more damning (needless to say, the circus association is much darker here than it is in Springsteen or Millhauser).

The second key condition or context of wonder, as explored in these three works, is that of entrapment. We see this play out most obviously in The Exterminating Angel, where Buñuel’s characters are, for mysterious and inexplicable reasons, trapped in the mansion’s music room, unable to pass an invisible barrier over the threshold. It is a scenario difficult to understand, until one looks at a more immediately accessible work like The Barnum Museum or The Wild & The Innocent and understands how profoundly applicable such an idea is to our daily lives. Just as Buñuel’s characters are trapped by wonder (or, at least, by some ‘wondrous’ or unknowable force), so are the characters of The Barnum Museum and The Wild & The Innocent.

“We know nothing except that we must,” says the narrator of his compulsion to “return and return again to the Barnum Museum” (90). With the Museum, life makes sense, and without the Museum, “we would experience a terrible sense of diminishment,” one that cannot be explained (90-1). While the story is written from the point-of-view of someone for whom the Museum’s wonder is still fresh, still powerful and engaging, one imagines – especially in the more melancholy or ambiguous moments of the piece, such as the ‘enough, almost enough’ concluding sentiment – that this inability to stay away from the Museum may ultimately prove harmful. Hannah Goodwin, we know, was lost to the Museum’s depths, obsessed with visiting and revisiting to the detriment of her social life, while the eremites, who refuse to leave the Museum’s walls, have been utterly cast out from society (82-3, 88-9). Given the previously identified significance of relationships and community, is this at all a desirable fate? Are the social divisions being made because of the Barnum Museum acceptable fallout, or the first signs of a deeper, irreparably damaging social schism? If the narrator cannot break out of his rhythms, visiting and revisiting the Museum constantly, will he too fall into these traps, and lose something important along the way? Going back to the primary question of this analysis, can the wonder of the Barnum Museum be sustained in perpetuity, or is a life spent chasing wonder in one place doomed to become stagnant?

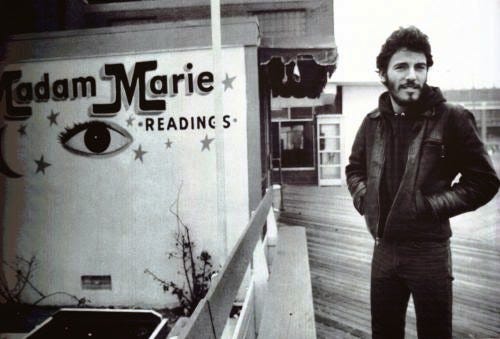

Wonder, paradoxically, is an inherently stagnating force. It entrances us, pulls us in, comforts us, bewilders us, and forces us to go back for more, because a sensation of wonder is a sensation worth chasing. But in that constant return to wonder’s point of origin, do we not run the risk of being desensitized, codified into playing the role of wonderer, without necessarily finding the ability to perform the crucial act of wondering? Such is the issue at the heart of The Wild & The Innocent, for although Springsteen’s nostalgic New Jersey is utopian and idealized in many ways, his characters exist at a pivotal crossroads, and none more so than the protagonist of “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy).” We meet the singer on his last night in town, before he blows away for somewhere new in the morning, and as such:

...The song describes a twilight of paradise. The arcades are dusty, the local fortune teller, Madam Marie, has been closed down by the police ... and the singer’s been dumped by the waitress he was seeing. This very personal post-lapsarian postcard develops the essence of a dead-end shore town decades removed from its heyday. (Kirkpatrick 23)

Indeed, while the singer has nothing but fond memories of his life on the boardwalk, he is acutely aware, at this point in his life, that they are nothing more than memories, and continued efforts to recapture the same sense of wonder this place once gave him will be self-defeating. The song is beautifully, inspirationally romantic, but measuredly so – the singer addresses a girl named Sandy, who Kirkpatrick identifies as a likely “metaphor for the Asbury Park shore,” and while he loves her in a way he never loved “all those silly New York virgins,” he has to let this be their last night together (Kirkpatrick 23; Springsteen, The Wild...). He wants it to mean something, and he wants it to be real, but he also tells her upfront that “I may never see you again.”

Bursting with the romance of purest nostalgia – a person’s love for the place that made them who they are – but also with the melancholy of moving on and letting go, “Sandy” is the most important track on The Wild & The Innocent, and, indeed, the critical piece of this entire analysis. For by choosing to appreciate the wonder of the past while actively pursuing a new and different status quo, the singer avoids the stagnation that may well befall the narrator of The Barnum Museum, and which has undoubtedly poisoned the characters of The Exterminating Angel (and some of the other characters on Springsteen’s record, such as Spanish Johnny in Incident on 57th Street, who throws away the good future he has with Puerto Rican Jane for another night trying to recapture the past with the “romantic young boys” he ultimately runs off with).

Buñuel’s characters are introduced to us at a point where wonder seems pretty heavily removed from their thoughts, even though they live amidst the kind of opulence that could fill many dozens of pages of Millhauser prose, or inspire several 20-minute jazz songs by Springsteen. Like many members of the bourgeoisie, they live life out of balance, not quite at ease in their own social structures (observe the awkwardness with which they talk and move amongst each other in the aftermath of the dinner party, and near the beginning of their long entrapment – the host Nobiles, for instance, do not even know how to ask their guests to leave, and turn instead to passive aggression), nor seemingly able to wonder at and appreciate their surroundings the way that Millhauser or Springsteen characters do. Even when wonder is thrust upon them, in the form of their invisible entrapment, these people cling, for a time, to social norms and etiquette, things which act to limit or reign in our capacities for spontaneity and wonderment. On one level, the entrapment seems a simple response to what these characters lack. Seemingly unable to engage with the opulence around them on any recognizable human or emotional level, the group is confined amidst the opulence, only being let free when they return to the evening’s original positions and start interacting more directly with the space and with each other, like they should have done at the start (put another way, they are forced to stagnate, as they do naturally in the outside world, until a breaking point is reached). But Buñuel, of course, has more complex intentions than just that, the surface narrative giving way to a searing metanarrative about religion, wonder, and the way we trap ourselves and stagnate in pursuit or ignorance of that which fulfills us.

There is an obvious metanarrative at work in The Barnum Museum as well. Multiple ones, actually, depending on which angle one approaches the short story from. Millhauser’s description of the Barnum Museum closely mirrors the experience of cinephilia, encapsulating the breadth of attractions, variety of ways in which people can engage, universal appeal, blockbuster spectacles (the “Chamber of False Things”), social debates (intended for children or a wider audience, the role of sexuality, etc.), cathartic qualities (the Hannah Goodwin story), debate over escapism versus substance, and inexplicably powerful sway that cinema has over those who are under its spell (73-4, 90, 80, 80-1, 78, 86, 82-3, 89-90, 90-1). Further exploration of the ‘Barnum Museum as cinephilia’ metanarrative is certainly deserving of individual analysis, but for our purposes, the parallel religious metanarrative is even more potent, for much of what can be read in the story as a metaphor for the experience of loving and engaging with art can also be viewed, in a slightly darker context, as a story about evangelization and religious entrapment.

For instance, while the story of Hannah Goodwin can be read in any number of ways – it is the universal scenario of a young person experiencing loss and retreating to a place that offers comfort – the idea of a person turning to God after a major trauma is such a widespread notion that it cannot be ignored. Is the Barnum Museum a sort of church for Hannah Goodwin, offering her wonder as a salve for grief, but only so long as she return, and keep returning, over and over again? The notion of religious doubt is hinted at shortly thereafter, when the narrator ponders the “times when we do not enjoy the Barnum Museum,” times which, because of the rage and confusion they cause, “only bind us to it in yet another way” (84). Like a religious person who experiences doubt or uncertainty, faith brings them back. The mysterious “museum researchers” who “work behind closed doors” seem eerily analogous to the notion of God – a tinkerer behind the scenes, who is known but never witnessed – the eremites are reminiscent of religious fanatics, and most importantly, the narrator’s defense of the Museum as something more than mere escapism – a defense against “those who do not understand us well” – recalls common arguments raised by those of deep faith, who claim the wonder of God affects and empowers them in all circumstances, not just when they are sad or vulnerable (86, 88-9, 89-90). But, again, there is a darkness to this story and an ambivalence to the note it ends on that suggests the wonder the Museum provides – or, in this metanarrative, the wonder the Church provides – is not perfectly sustaining, but instead in danger of stagnation.

Enter Luis Buñuel, who, as a surrealist and a man who lived under an oppressive religious regime in Spain, was heavily critical of religion in many of his films, The Exterminating Angel included. As Gwynne Edwards notes, “...freedom of all kinds lay at the heart of surrealist beliefs,” while Christianity, “based in part on the dictates of the commandments that ‘though shall not,’ was seen by the surrealists to be essentially restrictive of the freedom they worshipped...” (112). Buñuel was particularly disturbed by the Church’s intrusion into schools in his home country, where freedom of thought was limited from a young age, and given his strong belief in the importance of mystery and chance in life, something religion does not necessarily provide room for, Buñuel’s critical view of the church was a natural extension of how he viewed the world (Edwards 116, 118-9). The surrealists targeted the bourgeoisie for the “conventional values” they embraced, and with religion being foremost among those values, it is no surprise that “The close liaison between the Church and those sympathetic to the Right, particularly the bourgeoisie, is almost as much a focal point in Buñuel’s films as his emphasis on the bourgeoisie itself” (Edwards 112, 120).

If we then consider the music room the bourgeois characters are trapped in as analogous to a church, just as the Barnum Museum might be, the criticism becomes clear: Religion, like the Barnum Museum, or like the opulent bourgeois house, is something that offers us wonder, but not necessarily answers or true substance. Like the Barnum Museum, a church is something the devout keep returning to, over and over again, seeking hope, salvation, and meaning, but if it is not real, or if it is not enough (even if it is “almost enough,” as the Barnum Museum is), then in that place one shall stagnate, as one stagnates in any place, no matter what wonders are offered, if enough time is spent there without seeing and experiencing the rest the world has to offer. In this way, the Barnum Museum, the bourgeois house, and the metaphorical church are all limiting spaces, places that do offer meaningful wonder for those who are drawn in, but which shall ultimately constrain our capacity to engage with the world (including other wonders) if we rely on them exclusively.

One of the core dangers identified here, especially considering Buñuel’s belief in the importance of free thought, is that giving oneself up to one of these limiting spaces, including the church, reduces one’s ability to think freely. When one relies on someone or someplace else to provide one with wonder and with meaning, making that meaning on one’s own inevitably becomes difficult, as proven by the sheer amount of time it takes the bourgeois characters trapped in the music room to have a breakthrough. And even after this discovery is made, and the characters free themselves from their invisible prison, they immediately deny themselves free will once more, going to a literal church for worship, where the scenario of entrapment begins again, as it always has, and as it always will, so long as such people allow themselves to be entrapped.

Which, once more, leads us back to Bruce Springsteen and the characters of The Wild & The Innocent, who find wonder in a space without necessarily being limited by it. Interestingly, in an alternate version of “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)” Springsteen occasionally performs in concert (as early as 1975), the verse in which the singer confesses to being dumped by his waitress girlfriend is replaced with this far more inscrutable and provocative set of lyrics:

Sandy, the angels have lost their desire for us

I spoke to them just last night, and they said they won’t set themselves on fire for us

anymore

But every summer when the weather gets hot they ride that crazy road down from

heaven, on their Harley’s they come and they go

You see ‘em dressed like stars, in all them cheap little seashore bars, and parked with

their babies down on the Kokomo ... (Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, Hammersmith ...)

While the “Angels” are obviously meant to invoke imagery of biker gangs, it is impossible to ignore the equally apparent religious dimension here, especially when considering the implications of Buñuel and Millhauser. Much of “Sandy” is the singer’s self-justification for leaving the boardwalk life behind, and realizing that the “Angels” aren’t going to be there for him forever – that they will exist on this Boardwalk, just as the Boardwalk will continue to exist, but not in a capacity to assist the singer – is a pretty stern wake-up call to individuality. Springsteen allows room for religion and religious imagery here, while also recognizing that a life lived entirely dependent on religion – on the “Angels” – is bound to be a stagnating one. There will come a point when relying on one place or one set of ideas – one wonder – is no longer enough, and that moment has arrived for the singer, just as it should probably soon arrive for the narrator of The Barnum Museum, and as it should have arrived for the bourgeoisie of The Exterminating Angel long ago. Unlike those stories, The Wild & The Innocent is not a tale of stagnation. It is one of celebrating past wonders, making plans to experience new ones, and, in the final two tracks (“Rosalita” and “New York City Serenade”), busting the doors off one’s status quo and finding a new source of wonder for the next phase of one’s life (thus, “New York City Serenade” mirrors Side 1 opener “The E Street Shuffle” as a vivid description of place – and it is fitting that this new, unfamiliar place is described in much more surreal, lilting language). Unsurprisingly, Springsteen’s vision, with community, individuality, and wonder all working in harmony with one another, seems the healthiest of the three.

In contemplating the wisdom of The Wild & The Innocent, I am reminded of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The cave, where men are from birth kept watching shadows on a wall, is like the Barnum Museum, or the opulent bourgeois home – a space of abundant wonder, where one is accustomed to experience strange and fantastic imagery day in and day out, and which must, by sheer virtue of its repetition and invariance, lead to unfulfilling lives. To those inside, “the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images,” and while venturing outside and experiencing a whole world of new wonders would initially make those simple shadows preferable, making the effort to adapt oneself to these wonders would mean so much more in the end (“Plato...”). As Socrates explains:

... Whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort; and, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right, parent of light and of the lord of light in this visible world, and the immediate source of reason and truth in the intellectual; and that this is the power upon which he who would act rationally, either in public or private life must have his eye fixed. (“Plato...”)

Or, put another way:

Hold on tight, stay up all night ‘cause Rosie I’m comin’ on strong

By the time we meet the morning light I will hold you in my arms

I know a pretty little place in Southern California down San Diego way

There’s a little cafè where they play guitars all night and all day

You can hear them in the back room strummin’

So hold tight baby ‘cause don’t you know daddy’s comin’... (Springsteen, The Wild...)

Endnotes

1 - Before venturing any further, it is probably best to nail down a good abbreviation for this untenably long album title now, lest this paper balloon to several dozen pages from simple repetition of the name. Fans (on message boards, in online comments, etc.) typically abbreviate the title as WIESS, but given the crudity of such an acronym, I shall stick with calling it The Wild & The Innocent, which is what Springsteen himself typically calls the album when referring to it in concert (see Live 02-05-2014 Perth and Live 02-26-2014 Brisbane for examples). Elegant, catchy, Boss-approved, and stops us from confusing the album title with the name of the record’s first track, “The E Street Shuffle.”

Bibliography

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band. Hammersmith Odeon Live ’75. Columbia, 2006. MP3.

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band. Live 02-05-2014 Perth. Live Nation, 2014. MP3

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band. Live 02-26-2014 Brisbane. Live Nation, 2014. MP3

Buñuel, Luis. The Exterminating Angel. Trans. Chase Madar. Los Angeles: Green Integer, 2003.

Print.

Edwards, Gwynne. A Companion to Luis Buñuel. Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2005. 112-42. Print.

Emerson, Ken. “Bruce Springsteen: The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle.” Rolling

Stone. Rolling Stone, 31 Jan. 1974. Web. 13 March 2014.

Exterminating Angel, The. Dir. Luis Buñuel. 1962. The Criterion Collection, 2009. DVD.

Hepburn, R.W. “Wonder.” ‘Wonder’ and Other Essays. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,

1984. 131-54. Print.

Kirkpatrick, Rob. The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen. Westport: Praeger Publishers,

2007. 19-30. Print.

Millhauser, Steven. “The Barnum Museum.” The Barnum Museum. New York: Poseidon Press,

1990. 73-92. Print.

“Plato. The Allegory of the Cave.” The History Guide: Lectures on Modern European

Intellectual History. Steven Kreis, 2000. Web. 14 March 2014.

Sawyers, June Skinner. “Endlessly Seeking: Bruce Springsteen and Walker Percy’s Quest for

Possibility among the Ordinary.” Reading the Boss: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Works of Bruce Springsteen. Ed. Roxanne Harde and Irwin Streight. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010. 23-39. Print.

Springsteen, Bruce. The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle. Columbia, 1973. CD.

Read All 'Essay Day' Entries Here:

#1 – Heart of the Tramp: Charlie Chaplin’s Ethic of Dignity

#2 – Absolute Contingencies: The Double Life of Veronique, Under the Skin, Proteus, and the Wonder of Internalizing Art

#3 - Louis Malle’s Damage, Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, and the Circularity of Transgressive Energy

Jonathan R. Lack has been writing film and television criticism for ten years, for publications such as The Denver Post’s ‘YourHub’ and the entertainment website We Got This Covered, and is the host of The Weekly Stuff Podcast with Jonathan Lack and Sean Chapman. His first book – Fade to Lack: A Critic’s Journey Through the World of Modern Film – is now available in Paperback and on Kindle. Follow him on Twitter @JonathanLack.