Essay Day - "From Book to Cinema: Adaptation and the Construction of Film Noir in The Postman Always Rings Twice"

It’s Wednesday, which means it’s time for ‘Essay Day’ here at Fade to Lack. As explained here, I have a written a large number of essays during my time at the University of Colorado as a student in film studies, and I thought it time to share the best of those with my readers, so throughout the summer, I’ll be posting a new essay every Wednesday, all focused on film in one form or another, but often incorporating other research and fields of study.

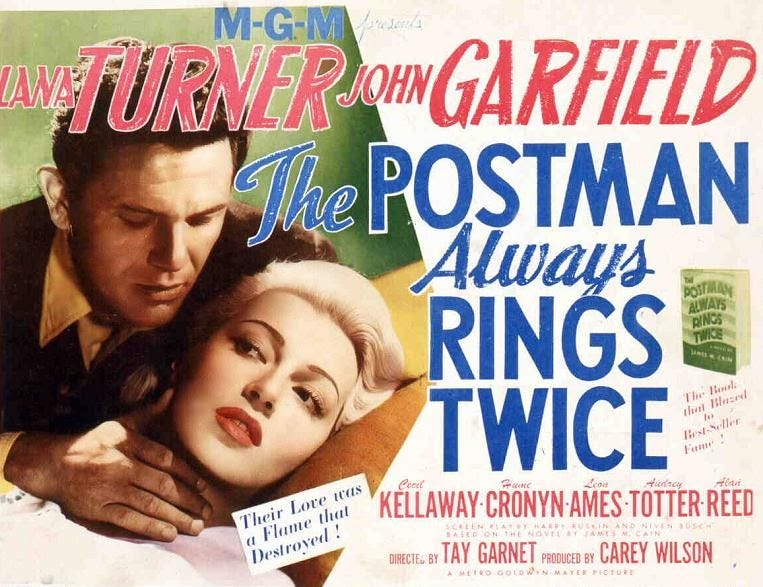

This week’s selection emerges from an interesting, challenging assignment. When I applied to the BA/MA program in Film Studies at the University of Colorado last October (a program in which one earns one’s Graduate degree at the same time as one’s Undergraduate), the biggest part of the application was the ‘October Surprise,’ in which applicants were given a film and a topic on Friday afternoon, and tasked with returning a 10-20 page research paper on the movie Monday morning. It’s quite sadistic in theory, but as I tend to write my major essays in concentrated bursts over a few days, this was actually quite enjoyable, as the film – Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice – encompassed plenty of possible paths for study, and made for a really fascinating research experience. This paper should be fully accessible whether one has seen the film or not, and offers an interesting look at Hollywood cinema during the height of the Production Code era. Enjoy...

Read “From Book to Cinema: Adaptation and the Construction of Film Noir in The Postman Always Rings Twice” after the jump...

A critical and commercial success upon its 1946 release, Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice is considered by “many the definitive postwar noir” (Dixon 16-7). While critical reevaluations from the mid-seventies onward vary wildly in their qualitative assessment of the film, it is undeniable that The Postman came about at the historical epicenter of film noir’s birth and maturation, and that its “quintessential” collection of “noir situations, collections of characters, and plot structures” makes it one of the most foundational and instructive entries in the American noir canon (Mayer and McDonnell 340). Like many early noir features, The Postman is based on a 1930s pulp novel; written by James M. Cain, the work itself marked, alongside several similarly hard-boiled contemporary books, the “beginning of (the) classic period of noir novels in the United States” (Faison 6).

Yet for a variety of reasons – many of them related to Hollywood’s extremely restrictive Production Code – the two noir traditions, literary and cinematic, differ greatly, a truth that is especially evident within The Postman Always Rings Twice. Garnett’s film displays a profound shift in content and ideology from the book upon which it is based, and while this was largely necessitated by the specifics of the Production Code, what makes the film so compelling, as both a historical curiosity and a (mostly) timeless viewing experience, is how it uses those restrictions to its advantage. By embracing the possibilities of adaptation as a means to find new and meaningful ways of expressing and expanding upon the barest narrative elements of its source material, rather than succumbing to mindless sanitization, the film offers a critical case study in understanding how film noir, working within the content limitations of the time, disassembles its literary antecedents and constructs itself anew as a unique and enigmatic cinematic tradition.

The Path From Page to Screen

David Madden calls James M. Cain “...the twenty-minute egg of the hard-boiled school,” and refers to The Postman Always Rings Twice as “the quintessential tough-guy novel...” (1). The ‘tough-guy’ novel evolves from the related traditions of “hard-boiled private detective” literature (which itself “departed from the genteel English novel of detection”) and “proletarian” novels (“derived from European naturalism and American selective realism”), and is distinguished by deeply ingrained pessimism, a stark reflection of the mood of the Great Depression – without making any overt political statements – and non-psychological forms of character development built around action, rather than inner or outer expressions of emotion (Madden 1-2, 12).

The Postman Always Rings Twice is indeed an exemplary model for ‘tough-guy’ literature. At a brisk and breathless 100 pages – which, Madden correctly notes, “may be experienced in one sitting” akin to a movie – the novel recounts the story of Frank Chambers, a drifter who arrives by chance at the Twin Oaks Tavern, where he not only finds new employment, but intense temptation in the form of Cora, beautiful and mysterious wife to tavern owner Nick Papadakis (38). After discovering mutual attraction in one another, Frank, who sees how unhappy Cora is in her relationship with “the Greek” – as Nick is most often called, resulting in a strong, omnipresent undercurrent of racial and ethnic tension that would be abandoned in Garnett’s film version – decides to help Cora kill her husband. After two attempts, Frank and Cora succeed, and are both set free in the aftermath of some complex legal wrangling, only for Cora to die shortly thereafter in a genuine car accident, with Frank sentenced to death for supposedly arranging her ‘murder.’

The book was an immediate success – and sparked a fair bit of controversy with its then-graphic depictions of violence, sexuality, and sadism – and MGM boss Louis B. Mayer bought the rights to the novel the very same year as its publication, in 1934 (Leff and Simmons 133). By the time the American film adaptation finally arrived in 1946, it belonged to a new wave of what would much later be dubbed ‘film noir,’ an “amorphous” and difficult to define film genre (Bould 14, Park 21). The debate over what does and does not constitute film noir – and what form the basic genre parameters, if they exist at all, should even take – is far too complex to touch upon too deeply here, and contrary to popular belief, the genre can in no way be easily summarized as a collection of “hard-boiled detective” films, nor as an assembly of common stylistic traits (Park 21-2). “No group of films, not even a single film encompasses all the characteristics of film noir,” writes William Park (22). Distilling the genre to its simplest and most universal components, we are left with, in Park’s analysis, “a crime, a fallible protagonist, a contemporary setting, and, usually, an investigation by someone or some agency, not necessarily the protagonist” (25-6). This is not a new combination of narrative elements – they can in fact be traced as far back as Oedipus Rex and Hamlet – but the specific ways in which these elements are cinematically realized – from a combination of aesthetic style, narrative structure, and, in my own analysis, treatment of character – makes for a genre that is undeniably “new” (Park 26). The Postman Always Rings Twice is, as previously noted, a perfect case study for this creation of genre, for the book (and the tough-guy tradition it helped create) is built entirely upon these basic components, and the film, though lacking in most of the identifiable aesthetic traits of the noir picture, evolves those narrative characteristics into something thematically and cinematically unique.

Tay Garnett’s film is largely true to the outline of the book, with few major changes made to the literal progression of the plot, but it differs greatly in tone, ideology, and characterization. Tone is the most immediate and obvious difference, and the one that paves the way for the more substantive deviations the film makes as it goes along. Where Cain’s writing style is stark and brisk, often written in harsh, staccato rhythms, Garnett’s film – written by Harry Ruskin and Niven Busch – is, at the outset at least, light and witty. Book and film alike depend heavily on dialogue – it is the main form of narrative momentum and characterization in each – but where the speech of Cain’s characters is largely bruised and repressed, Garnett’s cast trade clever, rapid-fire dialogue not only for function, but for personal amusement. Before and after the murder, stars Lana Turner and John Garfield wield speech like swords, dueling furiously with words to flirt, fight, size the other up, and to share honest displays of compassion, which are few and far between in Cain’s novel.

Perhaps most importantly, where Cain avoided “any discursive pauses that might interfere with the movement of his story,” and stringently avoided “psychological analysis,” Garnett’s film does pause occasionally for small, character-building moments, exchanges (typically between Turner and Garfield) that serve no literal function but are meant to add color and detail to the primary figures (Miller 52, Madden 2). And in so doing, psychological analysis does come to the forefront at times in the film; its characters, Cora in particular, are at once more enigmatic – their motivations less clear and their emotional states complex – and more knowable, because more time is taken to study and understand them.

In broad strokes, these tonal changes – the thematic implications of which we shall study in much greater depth later on – comprise the majority of surface alterations to Cain’s source material. They, along with other deviations, can in part be explained by the strict Hollywood production code of the time – though as we shall eventually see, critically distilling the altered nature of the movie entirely to these then-common creative impositions does the film an immense disservice.

The Postman and the Production Code

Initially imposed in the mid-1930s, and serving as the law of the land until the mid-1950s, the “awesomely repressive” Production Code, authored from strict, draconian Catholic principles and “prohibiting the showing or mentioning of almost everything germane to the situation of normal human adults,” made adapting The Postman Always Rings Twice a dubious proposition for the better part of a decade (Cook 237). The book was published, and the film rights purchased, right around the time the code came into effect, and it was generally understood – even by Cain himself, who admitted in 1946 that he wrote his books knowing they would “have censor trouble” – that any Hollywood adaptation would face serious hurdles (Madden 57). The book was practically a checklist of everything the Production Code forbade. As summarized by Leonard Leff and Jerold Simmons:

It was an understatement to say that The Postman violated the Production Code’s General Principles. The “sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin,” the first Principle read; Frank Chambers ... was an adulterer and a murderer. The second said, “Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented.” Chambers drank and fornicated; like Cora, he lacked moral compunction, and as he faced death asked neither God nor man or woman for forgiveness. “Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed.” In the courtroom charade of the latter half of the novel, Cain introduced two characters, one more cynical than the other: the district attorney and the defense counsel (130).

It was not until the 1944 film adaptation of Cain’s similarly challenging novel, Double Indemnity, that successfully bringing The Postman to the screen became viable. The Double Indemnity film removed some of the most ‘objectionable’ content from Cain’s book, but the core of the story was left intact, thus indicating that The Postman might have a similar shot at being told on film. “Producers called the release of Dobule Indemnity ‘an emancipation for Hollywood writing,’” explain Leff and Simmons, and that very same year, Louis B. Mayer returned to the property he had long considered a lost cause to see if a Production Code-acceptable outline could be created (131, 133). Mayer was intent on maintaining the core of the story, but he promised Production Code Administration president Joseph Breen that Frank and Cora’s “lust would be suggested rather than flagrantly expressed,” and adjusted in his outline many elements of the story to reflect more normative moral values (thus leading to the previously mentioned tonal variations, enhanced character introspection, and further justification and punishment for the central transgression) (Leff and Simmons 133-4).

These changes were enough to make The Postman fit for production, and perhaps the most impressive thing about the film Garnett eventually created is that, though most of its alterations to the source material were necessitated by the needlessly puritan ideology of the Production Code, the film is ultimately just as thoughtful and provocative, if not more so in places, than the novel it is based on (though critics who get hung up on the undeniably compromised ending would typically argue otherwise). It simply builds its drama in different ways, and operates on divergent thematic paths.

Consider the way Garnett handles his protagonists’ sexuality. Though unable to depict any physical contact more extreme than kissing and embracing, there is a strong, palpable atmosphere of sexual tension to their relationship, one that is created almost entirely through dialogue, performance, visual composition, and symbolical association.

These latter two elements are flawlessly combined in Frank and Cora’s first meeting, which must surely stand as the most sexually charged moment in either book or film. Frank is left alone by Nick to monitor a burger grilling in the tavern, when he hears a sound from the other end of the room. He looks to see a lipstick container rolling across the floor, and the camera, assuming Frank’s point of view, pans slowly to reveal the legs of a beautiful woman. She is Cora, looking absolutely stunning in a sultry white outfit, and while she and Frank exchange only a few sparse words, the sexual energy between the two is more than palpable, and is personified by the literal sound of sizzling emanating from the forgotten burger. This burger – left badly burned when Frank hurriedly returns to it after Cora has left – stands throughout the scene as an obvious but effective symbol for lust, while the cinematography, which combines elements of chiaroscuro (one of the only such moments in the film) with soft focus when framing Cora, emphasizes both her beauty and the dangerous nature of the impending relationship. There are many more sexually explicit scenes in the novel, and more even in the remainder of the film, but none that so powerfully use the artistic medium at hand to suggest attraction, nor the peril that might come from acting on it.

More common is the film’s use of dialogue to illustrate the sexual tension between the characters. As mentioned before, the writing is quite often intoxicatingly snappy, filled in the first half with humorous banter that Turner and Garfield work wonders with. And in some of the most deftly controlled moments of writing, the dialogue (and the specific, precisely calculated ways in which Turner and Garfield deliver it) suggests urges of repressed sexual passion as powerfully as any of the actual sex scenes in the novel. For example:

Cora: My husband tells me your name is Frank.

Frank: That’s right.

Cora: Well Frank, around here, you’ll kindly do your reading on your own time.

Frank: Your husband, Nick, told me I was through for the day, and I thought he was the boss around here.

Cora: The best way to get my husband to fire you would be to not do what I tell you to do.

Frank: You haven’t asked me to do anything...yet.

Notice that, even amidst the supposed banality of the exchange, Cora and Frank are subtly testing the limits of one another’s power, each suggesting dominance over, and hinting at wanting something from, the other. The first act is rife with exchanges such as these; the sexual overtones grow less veiled over time, but passion also takes on different contexts. In the second act, discussions of violence are added to Frank and Cora’s banter (“Listen to me Frank, I’m not what you think I am” ... “You couldn’t get me to say yes to a thing like this if I didn’t”), and in the third, all elements of wit and amusement are replaced by a general atmosphere of sorrow and regret, of introspective and strained affection (“Oh but love when fear comes into it”). No matter what, the dialogue, as written and performed, manages to effectively replace the overt sexuality of the novel with understated and pervasive chemistry. Frank and Cora’s doomed romance is expressed in extremely different, censor-friendly ways, but in ways that nevertheless have a strong impact on the viewer.

Garnett and company even manage to effectively translate and adapt the sadomasochistic aspects of Frank and Cora’s affair present in the book. The physical actions cannot, obviously, be depicted in the film – the moment, early on in the novel, when Cora asks Frank to bite her lip when he kisses her, and he winds up drawing blood, is viscerally disturbing even to this day – but Garnett still draws a connection between the lovers’ attraction and their propensity for violence. The third-act episode in which Kennedy, former employee of Cora’s defense attorney, Keats, comes to hold the couple ransom in exchange for the confession he took, makes clear and unmistakable connections between brutality and passion. After months of distance and tension in their relationship – this episode comes after Frank has cheated on Cora with a woman he met at the train station – Frank finds release in beating on Kennedy – it is the most savage thing he does in the entire picture, the blows genuinely shocking in their persistence and weight – and Cora clearly feels empowered holding the man at gunpoint. Violence thus ‘awakens’ the dormant emotions of the lovers in this scene, and leads to the single most passionate, sexually charged kiss in the entire film. Thus, there is something sadistic to this romance in the film as well – albeit without physical violence ever directed at one another – and it speaks to the unique thematic arc of the film’s take on the story, which shall be discussed at greater length in the next section.

Garnett’s film is in fact so adept at depicting passion that “though [the] screenwriters ... had cut much of the anger and feeling out of the novel, Breen predicted that ‘the overall flavor of lust’ would bring the censor boards down on The Postman” (Leff and Simmons 134). That did not come to pass, of course, due in large part to another concession Garnett made to appease not only the Production Code Administration, but MGM itself:

Had director Tay Garnett shot The Postman in the brooding style of film noir – strong on shadows and sparseness – he might well have put the wind back into the Breen sails. But the ambience of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer hardly encouraged Garnett to produce a cold and harsh Postman. Film noir thrived on pinched budgets and intellectual commitment, neither of which characterized MGM ... Garnett knew how The Postman should look to please not only Joseph Breen but Louis Mayer. When the picture entered principal photography in summer 1945, he bathed the sets in light and diffused the fatality of the story. (Leff and Simmons 135)

Indeed, this is one of the largest points of critical contention in discussions of the film. Though there were not, of course, any set conventions for film noir at the time – the term itself not coming into use for years to come – stories that were ‘noirish’ in their narrative construction and ideology obviously called, from the beginning, for “a consistency of vision and effect that compels recognition ... of a pervasive evil infecting the world in which the characters move” (Miller 55). The stylistic traits of the noir – dark environments, heavy employment of shadows, atmospheres of rain and grime – therefore extend naturally from the stories being told, and by being “brighter and glossier” than its noir contemporaries, most “evident in the lighting, which has much more fill and far fewer shadows” than what we typically associate with the genre, The Postman Always Rings Twice is an obvious outlier among noir pictures (Mayer and McDonnell 342).

But using this as proof of qualitative inferiority – as Gabriel Miller does when she accuses the style of “dissipating the impression of fatal passion on which Cain’s story depends” – is a case of historical bias, applying stylistic values we now associate with a genre filmmakers were not conscious of at the time to belittle a film that takes its own path to adapting its material. The film’s cinematography is, in truth, quite good, and if the majority of the film employs standard Hollywood three-point lighting, that only makes the moments that do rely on chiaroscuro or darkness – the aforementioned introduction of Cora, both murder attempts, and the final, emotionally powerful trip to the beach – stand out even more, with greater impact as a result.

Consider also the many thematic contrasts the lighting creates. While it is true that “Turner is always glamorously lit,” that only serves to make her seem more intriguing (Mayer and McDonnell 342). She is, after all, an extremely mysterious figure underneath that surface layer of glamour, and letting that truth be represented by a dynamic visual contrast (one that reflects what Frank sees in and feels about her) rather than directly mirroring her dark side through grim lighting is, to this critic at least, preferable. Garnett was a pragmatic filmmaker, and that his film managed to appease the Production Code Administration, MGM, and its own thematic interests in relatively equal amounts should be celebrated, rather than maligned.

The purpose of adaptation, after all, need not be the note-for-note replication of what the source material did well. The Postman Always Rings Twice strikes its own path out of necessity – there simply was no way, under then-current conditions, to make such replications – but it does so thoughtfully, as we have seen consistently throughout this section. These surface-level changes made out of Production Code requirements often give way to meaningful, provocative, and intriguing alterations to the substance of the story, including a largely wholesale reconfiguring of the plot’s thematic arc.

The Transformation of the Arc, and the Problem of the Ending

One of the most stringent requirements of the Production Code was “that the sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home be upheld at all times,” which creates an obvious problem in the third act of the story, once Nick is dead and Cora and Frank are living, unwed, under the same roof (Cook 237). While Cain waits until near the very end of his novel to have the two characters get married – prompted by Cora’s sudden, unexpected pregnancy – it is likely that, under Production Code restrictions, Garnett’s film did not have such a luxury, and so Frank and Cora get hitched shortly after Nick’s death, upon prompting from their defense attorney, Mr. Keats. There is no pomp or circumstance to the ceremony – just some legal paperwork and a certificate, which Cora dryly notes she will place “right alongside our beer license.”

Even as it assumedly exists in response to the censors, how this scene ultimately got past the PCA is a bit of a mystery. The moment comes when the film is at its most nihilistic: Frank and Cora’s love for one another has dissipated, and the marriage only takes place to appease those who might start asking questions (and to ensure that morally-minded people will not turn away from their business). That Cora equates a marriage certificate with a liquor license – reducing the so-called ‘sanctity’ of the institution to the same level as capitalistic red-tape – is a shockingly pointed bit of social commentary (and probably at least a little bit metatextual in regards to the policies of the PCA), and one of the most crucial thematic beats in the entire film.

Furthermore, the scene tells us everything we need to know about the extremely different thematic and ideological arcs of Cain’s novel and Garnett’s film. When Cain’s Frank agrees to marry Cora, it is out of moral obligation – he still has affection for her, and he wants to do the ‘right thing.’ For Garnett’s Frank, it is merely another concession he makes to a woman he is stuck with, another stop on the road of transgressions the two are committed to taking in their journey to prosperity. The differences are stark, because even as the two works share the same narrative fundamentals, the changes made in the film adaptation – including many, like the marriage, dictated by the Production Code – result in a thematic arc that is, right up until the terrible cop-out of an ending, the ideological inverse of its source material. Cain’s novel traces a journey from nihilism to humanity, while Garnett’s film (ending, again, excluded), moves in the other direction. The opposite ends the two works begin on can be seen from their respective opening moments, with Cain’s prose firmly entrenched in darkness and disillusion from its very first sentence:

They threw me off the hay truck about noon. I had swung on the night before, down at the border, and as soon as I got up there under the canvas, I went to sleep. I needed plenty of that, after three weeks in Tia Juana, and I was still getting it when they pulled off to one side to let the engine cool. Then they saw a foot sticking out and threw me off. I tried some comical stuff, but all I got was a dead pan, so that gag was out. They gave me a cigarette, though, and I hiked down the road to find something to eat. (1)

Notice how little Cain’s Frank seems to care about anything. He describes being “thrown off” a truck with the exact same amount of concern, regret, or investment as he does climbing on to it. For him, these are simply things that happened. They do not faze him, because his engagement in these events is minimal. He tries to make the others let him stay, but the language suggests only a modicum of effort was employed, and when he fails, he simply moves on. Frank’s attitude can properly be described as nihilistic; he sees no meaning in life, and he does not live to find any meaning, but to satisfy base, animalistic urges, like sleep, or food.

In short, Cain’s thoroughly disengaged Frank is a far cry from John Garfield’s Frank, whose first exchange in the film, shared with the then-unnamed District Attorney who drops him off at the Twin Oaks, is almost hilariously antithetical to the opening of Cain’s book:

Frank: Well, so long mister. Thanks for the ride, the three cigarettes, and for not laughing at my theories on life.

Sackett: But you broke off right in the middle of a sentence. Why do you keep looking for new places, new people, new ideas?

Frank: Well, I never liked any job I ever had. Maybe the next one is the one I’ve always been looking for.

Sackett: Not worried about your future?

Frank: Oh, I got plenty of time for that. Besides, maybe my future starts right now.

Not only is the cinematic Frank distinctly un-nihilistic, but outright idealistic, filled with broad, hopeful “theories” on the meaning of life and the fulfilling nature of chance encounters. Thus, we may say that while the book opens from a profoundly nihilistic perspective, the film begins from a place of fervent idealism. Even as both introductions get Frank to the Twin Oaks and to Cora, they approach that destination from entirely different ideological paths.

From there, Cain’s novel, dark though it may be, actually relates an arc that could be described as a humanistic awakening. Frank pursues Cora sexually based purely on animalistic urges – they share no flirtatious dialogue as they do in the film, and the word ‘love’ is used only as a shorthand stand-in for ‘the intoxicating passion of physical contact’ – and those urges are equally responsible for his choice to kill Nick. Unlike in the film, where Frank is prompted by Cora, a la Macbeth, to murder her husband, Frank suggests the idea in the novel upon seeing how miserable Cora is in her relationship (and, we may assume, to remove his rival for her physical affections). Yet after the murder, and upon witnessing first-hand what an utter sham the legal system turns out to be, Frank’s dormant humanity begins to come forth. He feels extreme, painful remorse for the crime he committed (described by Cain in terms we would now recognize as post-traumatic stress), and when he attends the Greek’s funeral, he actually cries, not only out of guilt, but because he actively misses this man who was kind to him. When he and Cora start to explore their relationship again, he realizes he really does care for her, on a level that goes beyond the sexual, and when he has an affair with the woman at the train station, he does so not because he is desperate to “get that blonde out of my system,” as Garfield’s Frank puts it, but because he feels hurt and vulnerable after Cora fails to return his affections.

In essence, Frank has gone from being an animal to being a human, capable of being driven by emotions, rather than urges. This makes the novel’s ending – extremely similar to the film’s, albeit without the saccharine explanation of the title – unexpectedly complex. Is it a final disavowal of nihilism, one that reaffirms order and meaning, however tragic and random, by having Frank and Cora each get what they deserve? Or is it a reassertion of the initial nihilist themes, one that tells us the only way to experience our inner humanity is to sin, and that sin invariably leads to further tragedy? Cain’s intention is probably a little bit of both, summarized by Frank’s own confusion in the final pages, where he cannot fully make sense of what has happened, but still has the capacity to hope that there may be salvation for him and Cora somewhere down the road.

In contrast, Garnett’s Postman opens idealistically, with its characters already existing as humans, and takes a turn for nihilism around the same time Cain’s Postman takes a turn for humanity. Specifically, it is when we start to see Cora’s understandable reasons for wanting to murder her husband that the notion of an unordered, fundamentally misguided universe is introduced into the picture. In contrast to the novel, where Cora is a thinly-sketched character who exists more as plot device for Frank’s arc than as a true standalone creation, Turner’s Cora is arguably the focal point of Garnett’s film as much or more so as Frank. Positioned as our window into this world, we experience through Frank’s eyes Cora’s complex emotional journey, in which Nick is, if not outright abusive, extremely uncaring and insensitive, his increasingly uncouth ways leading her to think of violence as her only way out. She believes she can commit this one transgression and then find happiness (and Frank, because he truly loves her for reasons that extend beyond the sexual, thinks so as well), but once the deed is committed, and she is betrayed by Frank during the trial, and made the legal play-thing of the vain Sackett and Keats, humanity is driven out of her. Her capacity to love goes with it, leaving a scorned Frank feeling just as bitter and pessimistic.

This is the point at which the aforementioned marriage license episode takes place – both characters are now in a state at which they would view marriage as little more than a business consideration – and the ransom encounter with Kennedy can also be seen as another step on the road to dehumanization. Frank is far more brutal and ruthless in his dealings with Kennedy than at any other point in the film, and as mentioned before, the ‘rush’ of violence briefly reignites a spark in Frank and Cora’s physical relationship. For these characters, animalism has now supplanted humanity, and the scenes leading up to the violent climax – which, like in the book, see Frank and Cora struggling to attempt a fresh start – are profoundly complex and thought-provoking in how they depict these two characters fighting to rediscover the humanity they realize has been lost.

It is likely that this fundamental alteration in arc is due, at least in part, to the requirements of the Production Code. An arc like that seen in Cain’s novel, in which violence makes characters discover emotions and become more sympathetic as a result, was downright antithetical to the word of the Code, whose “most labyrinthine structures were reserved for the depiction of crime” (Cook 238). However dark the overall context might be, a scenario in which crime leads to some form of benefit, even peripherally, was unacceptable – and so Garnett’s film had little choice, one would imagine, to adjust its ideology to reflect the dehumanization of violence, making Cora and Frank seem increasingly less sympathetic the more transgressions they commit.

Yet herein lies the fundamental hypocrisy of the Production Code: by making it so that Frank and Cora have to be dehumanized by their actions, the film is, at its best and most provocative, far more disturbing, and even more damning, than the book upon which it is based. The fallout of this reversal in arc, from humanity to nihilism, means that along the way, every social or political institution the film touches – capitalism, law, marriage, love, etc. – is almost savagely disassembled, revealed as platitudes and dismissed as meaningless. The world itself, it can be argued, is portrayed as fundamentally wicked. Most importantly, when Frank and Cora – both of whom are made to be sympathetic and likable at the film’s outset – suffer their fall from grace, it is truly piercing to watch. Rather than feeling as if ‘wholesome’ social values have been reinforced, the film instills even deeper, more hopeless pessimism than the novel; it hurts to watch, and it leaves the viewer doubtful of many moral and physical institutions we take for granted.

That, indeed, is the strength of the film – that from Production Code restrictions, it does not merely sanitize its content, but thoughtfully adjusts and meaningfully alters its messages, presenting a dramatic arc and worldview that is largely unique from its source material, yet no less valid or impactful.

Until, that is, we arrive at the film’s unfortunate ending, in which the tragic irony of Cora’s death and Frank’s execution is inexplicably spun into a hopeful moment of personal redemption.

As if especially designed to appease [the] Production Code Administration ... the closing scene brings in compensating moral values and underlines the fact that both killers are punished for their crimes. The film’s complicated title metaphor is explained in some mumbo-jumbo dialogue from Frank concerning messages from God, and he closes with a plea that the priest pray for him and Cora to be together through eternity. (Mayer and McDonnell 343)

It is certainly, as Gabriel Miller notes, “an incongruous note on which to end,” not so much for how it flies in the face of Cain’s original understated ending (which is primarily what offends Miller and several other prominent critics of the film), but because the scene is a complete and utter betrayal of the film’s own heretofore unique cinematic identity (63). Ending on a firm, glowing reaffirmation of humanity is not, simply put, the arc of this picture. As a story about two people discovering the true, dark depths of the world in which they live – and being gradually subsumed by those depths against their will – the film’s ending is utterly out of place. Even tonally, the scene is a complete embarrassment. With its soft, heavenly lighting and sappy, overbearing violin music blaring in the background as Frank recounts what he has learned, the scene reminds the viewer not of the film they have been watching, but of a very different MGM production: The Wizard of Oz, which The Postman’s final minutes borrow liberally from in structure, cinematography, music, and even language.

“The truth is, you always hear him ring the second

time, even if you’re way out in the backyard.

Father, you were right. It all works out.

I guess God knows more about these things than we do.”

“Oh, but anyway, Toto, we’re home. Home!

And this is my room, and you’re all here.

And I’m not gonna leave here ever, ever again,

because I love you all, and – oh, Auntie Em – there’s no place like home!

Jason Holt, a proponent of neo-noir as a superior and more fully realized version of the genre, argues that in this way, The Postman Always Rings Twice is indicative of many early, compromised noir pictures (38).

By contrast, the endings of classic noirs, an artifice of the Production Code and compliant creative intentions, almost always ring a little off, false, not only to life, but, much worse, to themselves. A most unfortunate illustration is The Postman Always Rings Twice, an otherwise fine noir that ends with Frank explaining, for the audience, that poetic justice has been received! (Holt 38-9)

There is validity to Holt’s point. Certainly, the undermining of the film’s noir merits due to production code considerations is a more meaningful complaint here than it is anywhere else (and a much more substantive complaint than those aimed at the film’s aesthetics). Whether one is offended by the lack of faithfulness to Cain’s book or to the preceding 110 minutes of cinema, The Postman’s ending is unfortunate, an undeniable blemish that cannot be ignored.

Yet in the end, it is ultimately a matter of perspective. Do we damn the entire film for its horribly botched conclusion, as many critics cited here have done? Or do we view it as a minor miracle that, given contemporary Hollywood conditions, the film made it to that regrettable scene relatively unscathed? There are lessons to be learned here, and the majority of them are positive. For the times in which they lived, Garnett and company were handed an immensely challenging project, and rose to the occasion by thoughtfully, perceptively, and even provocatively adjusting their story to say something different, but no less meaningful, than the source material they were barred from staying completely faithful to. With a unique arc, a different visual and linguistic style, and even an alternate view of character, Garnett’s Postman stands on its own, and stands reasonably tall (in truth, the ending stings as much as it does because the film had so far to fall).

Early film noir was not constructed under ideal conditions, but if it had been, would the genre that was ultimately created now be considered so distinctive? The Production Code ensured that straight translations from 1930s ‘tough-guy’ novels to 1940s crime pictures were impossible to produce, and that meant filmmakers like Garnett had to strike out in unique cinematic and thematic directions. Had circumstances been different, we may have seen a series of pictures more uniform in their ideological and visual design – and thus easier to define as a genre – but that would have come at the cost of an identity unique from literary antecedents. Travesties like the last five minutes of The Postman Always Rings Twice may be the price we pay for film noir’s ultimately successful and distinctive birth, and no matter what, the countless things Garnett’s film does right should not be penalized for the one big moment it gets all wrong. For noir especially, cinematic adaptation is a turbulent path, and while such turbulence is fraught with obvious downsides, it can also, as Garnett’s film clearly demonstrates, lead to inspiration.

Bibliography

Bould, Mark. Film Noir: From Berlin to Sin City. London and New York: Wallflower, 2005.

Print.

Cain, James M. “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double

Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Selected Stories. James M. Cain. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003. 1-106. Print.

Cook, David A. A History of Narrative Film. 4th ed. New York and London: W.W. Norton &

Company, 2004. Print.

Dixon, Wheeler Winston. Film Noir and the Cinema of Paranoia. New Brunswick: Rutgers

University Press, 2009. Print.

Faison, Stephen. Existentialism, Film Noir, and Hard-Boiled Fiction. Amherst: Cambria Press,

2008. Print.

Holt, Jason. “A Darker Shade: Realism in Neo-Noir.” The Philosophy of Film Noir. Ed. Mark T.

Conrad. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006. 23-40. Print.

Leff, Leonard J., and Jerold L. Simmons. The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and

the Production Code. 2nd ed. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001. Print.

Madden, David. Cain’s Craft. Metuchen and London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1985. Print.

Mayer, Geoff, and Brian McDonnell. Encyclopedia of Film Noir. Westport: Greenwood Press,

2007. Print.

Miller, Gabriel. Screening the Novel: Rediscovered American Fiction in Film. New York:

Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1980. 46-63. Print.

Park, William. What is Film Noir? Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2011. Print.

Postman Always Rings Twice, The. Dir. Tay Garnett. Perf. Lana Turner and John Garfield.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1946. DVD.

Read All ‘Essay Day’ Entries Here:

#1 – Heart of the Tramp: Charlie Chaplin’s Ethic of Dignity

#2 – Absolute Contingencies: The Double Life of Veronique, Under the Skin, Proteus, and the Wonder of Internalizing Art

#3 - Louis Malle’s Damage, Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, and the Circularity of Transgressive Energy

#4 – Fire Trails on Silver Nights: Representing Wonder and Balance in Three Works by Luis Buñuel, Bruce Springsteen & Steven Millhauser

#5 – Bond on Bond: Quantum of Solace and the Elusive Case of the Bondian Ideal

#6 – Is Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan Documentary Not?

#7 – Realism and Character Study in Agnes Varda’s Cleo From 5 to 7

#8 – Maya Deren in 3D! Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, and Cinematic Visions from the Beyond

#9 – Suffering and Transcendence in Federico Fellini’s La Strada and The Dardenne Brothers’ L’Enfant

#10 – Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back, and the Reflexivity of Direction

Jonathan R. Lack has been writing film and television criticism for ten years, for publications such as The Denver Post’s ‘YourHub’ and the entertainment website We Got This Covered, and is the host of The Weekly Stuff Podcast with Jonathan Lack and Sean Chapman. His first book – Fade to Lack: A Critic’s Journey Through the World of Modern Film – is now available in Paperback and on Kindle. Follow him on Twitter @JonathanLack.