Essay Day - "Hana-bi, Battle Royale, and a Theory of Transgressive Transcendence"

It’s Wednesday, which means it’s time for ‘Essay Day’ here at Fade to Lack. As explained here, I have written a large number of essays during my time at the University of Colorado as a student in film studies, and I thought it time to share the best of those with my readers, so throughout the summer, I’ll be posting a new essay every Wednesday, all focused on film in one form or another, but often incorporating other research and fields of study.

This week’s piece was written for a class on “Cinema and the Poetics of Transcendence” in the Spring of 2013. As the name implies, the course explored films dealing with themes of transcendence, and the assignment for this final paper was to pick two films not discussed in class dealing with the topic and write an analytical essay about them. I was interested in a common theme throughout the course of violent, dark acts appearing in the films we watched, despite the uplifting connotation of the term ‘transcendence,’ and thus picked two movies that deal very directly with violence and absolution – Takeshi Kitano’s Hana-bi and Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale. Both, incidentally, probably hold a spot in my top ten favorite films of all time, so these are movies I love deeply, and this essay was therefore an important one to me. Enjoy...

Read “Hana-bi, Battle Royale, and a Theory of Transgressive Transcendence” after the jump...

Is it possible to attain transcendence through hardship? Can trauma force us towards moments of profound realization that alter the courses of our lives, or raise our minds to higher levels of consciousness? Can an encounter with the darkness and evil of our world lend us a greater understanding of love and friendship? Do acts of moral transgression lead us to deeper truths about the nature of humanity, or of our own personal identities?

These are the questions directors Takeshi Kitano and Kinji Fukasaku ask in their respective films Hana-bi and Battle Royale1, each work presenting a path to transcendence wherein one may only truly transcend – understanding the world both for what it is and for what it can be – after a severe trauma opens one’s eyes to the worst human life has to offer. The characters of these films take very different courses to achieve transcendence, but transgression is a key element of everyone’s arcs.

In Hana-bi, Takeshi Kitano argues, through a dual-protagonist structure, that those seeking transcendence must perform moral transgressions, in order that they might understand, synthesize, and ultimately surpass both the violent and gentle qualities of the human spirit to find a higher, more spiritually fulfilling state of being. In Battle Royale, Kinji Fukasaku illustrates one of the most horrific circumstances imaginable to explore whether or not innocence can survive in an inherently violent world, and ponders, through a richly developed ensemble and the employment of dream sequences, how humans – both young and old – may find transcendence if this is not the case. In each film, an acceptance of both the world and the human condition for what they truly are – violent, sad, and utterly flawed, though not without room for beauty and redemption – is essential in charting a course towards transcendence. The films themselves may be called ‘transcendent,’ for in their unflinching dramatizations of such dark and disturbing material, Kitano and Fukasaku create not an impression of hopelessness, but a miraculous and inspirational image of the grace that lies beyond human suffering.

The Fire and the Flower2

When Hana-bi was first brought to the United States in 1998, it was released under the title “Fireworks.” Disregarding the content of the film itself, this is a logical translation, for the objects we call ‘fireworks’ are identical to what the Japanese call ‘hana-bi(花火)3.’ Yet in relation to the basic thematic framework the film’s original title represents, this is a wholly inaccurate and ignorant adaptation, for a crucial cultural and linguistic element is lost in translation. In Japan, these objects are named, rather poetically, for a combination of “fire(火)” and “flower(花).”

And so it goes for Hana-bi the film, which is, at its core, an exploration of how ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ work at odds and in harmony within the complex labyrinth that is the human spirit. As noted Kitano critic Casio Abe puts it: “The title ... seems to imply not the opposition of “flower” (life) with “fire” (death), but rather a mutually inclusive relationship (239-40).”

Indeed, the ‘fire’ and the ‘flower’ represent many related concepts in Hana-bi, with ‘life’ and ‘death’ being the broadest and most immediate parallels that can be drawn. The film targets many more specific associations, such as an early jump cut that moves from Detective Nishi (Beat Takeshi4) lighting his cigarette to the firing of a gun – the shot that will paralyze Detective Horibe (Ren Osugi). ‘Fire’ and ‘violence’ are therefore immediately, inextricably linked in the mind of the viewer, and from this point on, we shall view all further acts of violence as stemming from a place of ‘fire.’ Similarly, a sequence where Detective Horibe stops by a flower shop depicts flowers as providing a doorway to profound emotional revelations. The flowers create a spark for Horibe’s artistic drive, as he begins envisioning the paintings he shall eventually create while looking at them, and is visibly overwhelmed by the beauty they have to offer. In this moment, flowers are synonymous with emotion and beauty, as they shall be throughout the film.

We can find further allegorical parallels between ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ by assigning one of these two words to each of the detectives. Nishi’s penchant for violence (he physically hurts others in brutal, grisly outbursts throughout), connection to the urban city setting (his most notable actions in the film’s first half occur in a mall, a junk yard, and a bank), general detachment from ‘life,’ and marriage to a dying woman all firmly establish him as the film’s central manifestation of ‘fire.’ Through his actions, we see that ‘fire’ not only symbolizes ‘death’ and ‘violence,’ but also non-natural settings and transgressive impulses. Meanwhile, Horibe’s more overt expression of emotion (both men are repressed, but Horibe is quicker to talk about his feelings, and Ren Osugi plays him as easier to physically read than Nishi), passion for art, and connection to natural settings (past his point of paralysis, he will mostly be seen at the beach) cements him as the embodiment of ‘flower.’

The actions the two men take are often shown as contrasts – Nishi chooses to die alongside his wife while Horibe goes on living, Horibe is abandoned by his family while Nishi becomes closer to his wife, etc. – but as Abe notes, it is more valuable to look at the ways ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ are connected, and the places at which they blur. There is an omnipresent sense of unison between the two elements, emanating down from the title, in which they are linked, on to every other element of the film.

Take, for instance, the paintings littered throughout the film. Drawn by Kitano himself (who took up pointillism following his motorcycle crash, just as Detective Horibe does in the film), these works of art are seen in nearly every interior setting and among a variety of contexts. When Nishi brutalizes a yakuza gangster with chopsticks in a sushi bar, a painting hangs on the wall, and when he later robs the bank, there is a painting of sunflowers in the background. A close examination of the film reveals, in fact, that every instance of violence (fire) is accompanied by a representation of ‘flower,’ whether through Kitano’s paintings or, in the second-half, by framing the violence against natural landscapes like the beach.

Kitano’s implication is that ‘violence’ and ‘nature’ are in a constant state of coexistence – that violence is natural and that nature is violent. Because Detectives Nishi and Horibe inhabit the dual spaces of ‘fire’ and ‘flower,’ and are compared and contrasted with one another both literally (two bodies sharing screen space) and figuratively (paintings similar to Horibe’s dogging Nishi, Nishi’s gifts of art supplies and embroidered charms emboldening Horibe), their link is equally inseparable. Indeed, Nishi and Horibe are arguably one spirit separated into two semi-distinct halves, operating on different trajectories from different starting points but existing within the same unified space of ‘hana-bi.’

The movement towards transcendence the film exhibits, then, is one of escaping the singular spaces of ‘fire’ or ‘flower’ to reach a personal synthesis between the two, as the title implies. This transcendental journey stems from a profound sense of ‘paralysis’ that makes the characters feel ‘trapped.’ For Detective Horibe, this paralysis is literal; after being shot at a stakeout, he loses use of his legs, and feels further disconnected from the world when his wife and daughter abandon him. Detective Nishi is already paralyzed, in a sense, by his own inability to connect with the world around him – he is silent and detached at nearly all times – and by his grief.

Before the film opens, he and his wife have already lost a young child, and we learn early on that his wife is dying of cancer with no chance of survival. The vengeful retaliation he takes against Horibe’s shooter – killing the man and proceeding to empty his gun barrel into the corpse – loses Nishi his badge, further compounding his spiritual paralysis.

For Takeshi Kitano, this theme of paralysis is deeply personal. In 1994, he was involved in a horrible motorcycle accident “in which he avoided sudden death by a margin of a few seconds,” and saw the right half of his face paralyzed (Abe 200). Hana-bi would be the first time he performed in a film following this incident, meaning that his own paralysis would, by necessity, now be part of the fabric of his work. If Nishi and Horibe are indeed two dissociated halves of one larger spirit, they are split from Kitano himself. He may only perform as Nishi, but he is Horibe as well, and the separation is necessary to illustrate the transcendental value he sees in both life and in death.

Both Nishi and Horibe will ultimately synthesize their ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ halves, and thus transcend to become ‘whole,’ but they shall take different paths to do so, and create their final synthesis through extremely different resolutions. Horibe is the first to locate his path. After being paralyzed, he makes constant trips to the beach5 and spends most of his time among nature, unconsciously retreating to places within his own safe, personal realm of ‘flower.’ He quickly begins to ponder painting as an outlet for his emotions, and thus sets himself on a course of healing, and towards transcendence.

Nishi’s road is much more complex and serpentine. Like Horibe, his ‘paralysis’ sends him retreating to his personal space; being ‘fire,’ though, this makes Nishi violent. Both men are searching, in part, for means of communication, as words cannot describe the pain and isolation they feel, but while Horibe’s artistic outlet is healthy, Nishi’s use of brutality to express himself is much more damaging. As a result, Nishi only traps himself further – in depression, in yakuza debt, and in distance from his dying wife.

Nishi, it becomes clear, must make a movement away from ‘fire,’ which is brash and isolating, to the realm of ‘flower,’ where he can find healthier means of communication and make his life more fulfilling. He will achieve this, for the most part, in taking his wife out of the city (a place associated with ‘fire’) and vacationing with her in beautiful landscapes around Japan, places of ‘flower’-like purity. Once this move from ‘fire’ to ‘flower’ is complete, Nishi does indeed transcend his own paralysis. He begins to laugh more. He smiles. He and his wife enjoy one another’s company immensely, and while they do not talk – speech is inadequate in almost all situations throughout the film – they communicate through shared laughter, usually born from silly mistakes (the firework failing to go off, Nishi cheating at the psychic card game they play, a car passing by as they attempt to take a time-delay picture together, etc.).

But for this movement from ‘fire’ to ‘flower’ to occur, Nishi must commit a moral transgression, and here is where we see the most provocative complexities of Kitano’s message begin to take shape. Before leaving town, Nishi must accrue funds, not just for the trip, but to pay off his wife’s medical bills and to settle his debt with the yakuza. Otherwise, he and his wife cannot leave town cleanly. Thus, Nishi decides to rob a bank6. He does not hurt anyone, but this total betrayal of his former ethics and occupation – symbolized by his use of a police uniform and fake police car to perform the heist – is nevertheless a major transgression.

Yet as presented in the film, the transgression is necessary to break through the wall that separates ‘fire’ and ‘flower.’ Or at least, this is our (and Nishi’s) understanding of how the movement from one realm to another works at this moment in time. The thematic point Kitano aims for is more complex than mere nihilism or cynicism, for after Nishi makes a seemingly ‘complete’ transformation – fleeing to nature, growing infinitely closer to his wife, and gaining a measure of true, unsullied happiness – his past transgressions come back to haunt him. The yakuza, angry at Nishi for the arrogance and violence he showed them, chooses to come after Nishi even after he has paid them off, and when they find him in the ‘natural’ setting he now inhabits, Nishi returns to his violent ‘fire’ instincts.

At one point, he even hurts an innocent, albeit belligerent, man who approaches his wife. “Hey, it’s no use giving water to dead flowers!” the man says, seeing the woman doing just this at the beach. He continues to pester her, until Nishi savagely beats the man to the ground and holds his head under water. Nishi does not necessarily do this on his wife’s behalf – she is strong enough not to be shaken by this – but because giving water (a life force) to a dead flower (his wife, Horibe, and of course himself – all close to death or ‘paralyzed’) is the current purpose of his life, and he cannot abide by someone placing doubt upon his transcendence.

But doubt is indeed in place. Nishi commits violence in nature. He profoundly blurs the lines between ‘fire’ and ‘flower,’ lines he, and the audience, thought he had surpassed. Thus, a realization is forged: That ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ are not separate realms one can move between, but separate concepts that exist within one extremely complex and demanding world. In the end, Hana-bi illustrates the very same realm its title suggests, one where ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ are often found atop one another, violence and nature coexist, vicious men have natural, emotional impulses, and sensitive men have violent, transgressive urges.

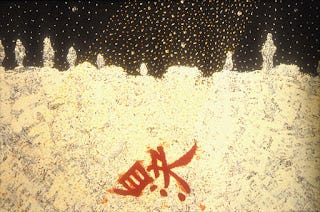

For Horibe, too, commits a transgression only to find that it alone will not lead him to transcendence. He attempts to kill himself, an act of violence that seems more in line with Nishi’s attitude, but when this fails, and he redoubles his efforts towards painting, he too silently accepts that the world is more complex than he had estimated. The final major art piece he creates is a visual expression of what he now feels. It is a snowy, nighttime landscape, with kanji for “snow(雪)” and “light(光)” acting as snowflakes, all falling atop a massive kanji for “suicide(自殺).” The elements of ‘fire’ and ‘flower’ are omnipresent in this image, but the split between them is not clear cut or simple. ‘Snow’ and ‘light’ are both natural, but can have dark or violent edges to them, and they are depicted as leading towards suicide.

At this point in the film, the connection between Horibe and Nishi is practically psychic, for this painting – Horibe’s final action, an ironic declaration that he will go on living and creating – is the artistic equal to Nishi’s final action: Committing double suicide with his wife on the beach.

Before the final two gun shots, while Nishi and his wife play with a young girl and her kite by the ocean, Detective Nakamura, a younger officer sent to apprehend Nishi after learning of the older man’s violent eradication of the yakuza forces, remarks that he “would never be able to live like that.” Perhaps he refers to this mixture of violence and nature that Nishi exhibits; of being a murderer but enjoying play at the ocean with his wife. Indeed, such a fused dichotomy is difficult for a young man to comprehend, just as Nishi and Horibe saw the world as more fragmented at the film’s outset. Nakamura too is an incarnation of Takeshi Kitano, one who has not come to see and appreciate how connected the ‘fire’ and the ‘flower’ truly are. He will, though, just as Nishi has. Nishi’s true transcendence comes in discovering this dichotomy, internalizing it, and, in his final moments, using violence – a transgressive action – to gracefully exit this world with the woman he loves while staring out upon an image of infinite beauty.

The title, Hana-bi, refers most strongly to this last scene, where, in the middle of beautiful, eternal, never-ending nature – the ocean, in its purest form – Nishi will use ‘fire’ (violence) to become one with these surroundings, and to do the same for his wife. He ‘transcends,’ eternally, not from ‘fire’ to ‘flower,’ but to ‘hana-bi,’ the same motion Horibe makes in learning from a near-death experience to craft a painting that obliquely summarizes this journey. In the end, they are each ‘hana-bi,’ one in life, and one in death, transcendent both individually and together.

The Greatest Battle – A Loss of Innocence7

Casio Abe describes Hana-bi as having a strong “tendency towards plurality,” referring to its dual-protagonist structure and the blurring of thematic lines between them, along with the employment of flashbacks and montage editing (237). Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale is no less pluralistic in its construction. It features a vast ensemble, also employs flashbacks and montage, and its use of space – cutting between many individual spots on the island to create a holistic view of the area and circumstances, and connecting characters within these isolated spaces through complex, rigorously placed action sequences – is itself pluralistic.

Yet Hana-bi, as we have seen, displayed a strong ‘foreword movement’ towards transcendence in the midst of its plurality (or, perhaps, because of it), and Battle Royale operates the same way. It retains the same ‘transcendental momentum,’ propelling itself forward at all times towards a heightening of consciousness and amplification of spiritual strength. This momentum comes, as it did in Hana-bi, from the profound awareness the characters gain of the true nature of the world in which they live.

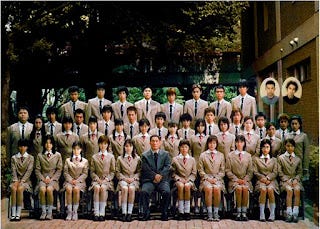

It is a harsh world, as personified by the film’s central premise: That of a horrific government program, established in a dystopian alternate-history Japan, where a class of 42 high school students, aged fifteen, is selected every year to compete in a battle to the death where only one adolescent may survive. Fukasaku felt a highly personal connection to this material, for during World War II, while in middle school, he survived a bombardment and was forced to dispose of the bodies; “It left a great impression on me,” he said (Fukasaku, “Living Through War,” 582-3). In a ‘Director’s Statement’ released alongside Battle Royale8, Fukasaku revealed that the dead were his classmates, all drafted to work in a munitions factory, and that the emotions he developed there – including a “poisonous hostility for adults” – are “the point of departure for all my films,” and that “Battle Royale ... returns irrevocably to my own adolescence (Fukasaku, “Director’s Statement,” 1).” Sociopolitical ideas Fukasaku would develop as an adult in Japan’s postwar period also feed into his fascination with the Battle Royale story, for “defeat in World War II brought with it an era Fukasaku sees as quasi-democratic and full of uncomfortable contradictions. On the one hand, the individual was liberated from a great many traditional constraints; on the other, the stage was left free for an ugly anarchy as new forms of egotism and nationalism asserted themselves (McDonald 21).”

Does this not sound like the foundation for Battle Royale, a nightmare scenario where the unwilling participants are, in a sense, ‘free’ to indulge their basest instincts, but only within the abusive boundaries of a deeply broken, fearful, and insecure government? The film is not strictly allegorical to any one period or event, but as a heightened evocation of what Fukasaku sees as modern life – a way of living that is brutal, competitive, and unfair, and where it is often impossible to rely on others – the film is built on provocative insight into not only Japanese society, but universal flaws in modern culture worldwide. Fukasaku tells this story not to create violence for the sake of violence, but to comment on how one might live in and transcend above the world we inhabit, and to ruminate on the generational issues that haunted him all his life.

What becomes immediately apparent, as the program gets underway, is that innocence cannot survive in this world. One of the first deaths is a double suicide, committed by teenage lovers Sakura and Kazuhiko. “I’ll never play this game,” Sakura says, a sentiment her boyfriend shares. They desire to maintain their innocence, but under these circumstances, they cannot do so while living, and therefore choose to die by jumping off a cliff. The film then cuts to another student, Megumi, who looks very ‘innocent’ as she examines pictures of her crush, classmate Shinji Mimura, while hiding. Mitsuko, a girl who becomes a primary force of death throughout the film, finds Megumi, and plays on her innocence to kill her by surprise. “That’s not my scene,” Mitsuko explains as she slits Megumi’s throat, referring to two other students who hung themselves a short ways away.

A rejection of innocence is thus equated with transgressive actions, and a maintaining of innocence leads directly to death. The message is cynical, but clear: That to live in this world, innocence must be shed. The film’s protagonist, Shuya Nanahara, learns this the hard way when he is forced to fight back against Oki, a boy who brandishes an axe at Noriko, the girl Shuya has sworn to protect. Doing so means killing Oki, and even though it happens by mistake, Shuya must now come to terms with the fact that he is no longer ‘innocent.’ As the film progresses, and Shuya and Noriko join with Shogo Kawada, a slightly older boy who has previously survived the program and therefore understands that violent transgressions are essential to continue living, this displacement of innocence comes in to sharper and sharper focus, and the lines between characters no longer contrast ‘innocence’ with ‘non-innocence.’ As Fukasaku puts it, “The movie thematically breaks it down into two sides: those who instigate violence, and those who have violence instigated against them (Fukasaku, “Living Through War,” 585).” At a certain point, neither side is innocent, and both commit transgressions to survive. What then distinguishes Shuya and company from characters like Mitsuko is whether or not they actively seek out opportunities for transgression.

Yet as in Hana-bi, those who transgress with a larger purpose in mind (like Shuya fighting to protect Noriko) are not uniformly lost to violence and despair, but often encounter moments of true, pure transcendence. Battle Royale is, in fact, littered with such moments. To ‘transcend’ simply means to “rise above or go beyond the limits of,” meaning that any time a character finds something beyond the utter darkness of the death program, transcendence has occurred (“Transcend,” Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

Shuya, Noriko, and Shogo find such transcendence in each other’s company through the simple act of friendship. Being there for someone else in a meaningful way, offering insight into one another’s lives and creating a mutual sense of catharsis and healing, truly is a transcendent action, especially in circumstances as horrific as this.

Classmate Chigusa, meanwhile, will find something similar when she dies in the arms of her best friend Hiroki. The horror of the situation is absolute, but by remaining friends to the end, and being together to experience a moment of deep kinship one last time, Chigusa and Hiroki do find a measure of transcendence, an escape from the terror of the moment that allows them to feel the beauty of life, at least for the briefest of moments. “You look really cool, Hiroki,” Chigusa says after begging God for the strength to say one more thing. “You do too,” Hiroki replies. “You’re the coolest girl in the world.” They each get to say what the other needs to hear, and though one shall move on in life and one in death, each walks away having experienced something so much greater than the petty violence of the Battle Royale.

Such beautiful sequences rise out from the chaos and carnage time and time again, and each has an extreme emotional impact. Fukasaku is as skilled at bringing genuine, heart-wrenching human emotion out of his young actors as he is at staging action and violence, and the impact of one only exists because the impact of the other is equally severe. In any case, while these many moments of individual transcendence form part of the film’s pluralistic structure, they all point towards the film’s larger thematic purpose and endgame, thus contributing to the aforementioned ‘transcendental momentum.’

This momentum comes to a head late in the film, when Shuya, returning to Shogo and Noriko after sustaining extreme injuries, falls to the ground, in Noriko’s arms. He has brought a great number of weapons with him, even though he can barely walk, and Noriko, confused, asks him why he has done this. “I’m weak, and useless,” Shuya explains. “But I’ll stay by your side. I’ll protect you. That’s why I brought weapons.” It is one of the most emotionally hard-hitting moments in the film, for it is preceded by a flashback where Shuya recalls how his father, who committed suicide a year earlier, was never truly present the way Shuya needed him to be. Shuya resolves to not be like his father, to overcome where those who came before him faltered, and to never succumb to the terrors adults are now putting he and his friends through.

In many ways, Shuya’s words and actions here epitomize Battle Royale. He has lost his innocence, and been forced to commit transgressions, but he now accepts and internalizes these harsh truths, and is willing to fight and transgress again if need be, because if he does not, he will be no better than his father, or the adults who instituted this program. Shuya’s revelation is one of the keys to finding transcendence in the film: That one cannot reject or run from the dark realities of the world as it exists, but must learn to live within its boundaries, even if those boundaries are difficult or barbaric. Things like love and friendship can exist, and their beauty and radiance are what allow us to overcome what is bad in this world, but one must live to experience them, and living does not mean running from the truth. It means confronting the darkness wherever it exists, and pushing on through with a goal in one’s heart. Shuya now has this. There are long ways left to go, but he has at least begun to transcend the limits of this world.

This is also the point at which themes of generational conflict take center stage. A severe misunderstanding between the old and young is central to Battle Royale, partially because the film reflects Fukasaku’s own wartime trauma. Despite this, Fukasaku does not make the adults a one-sided, villainous entity. Kitano, the administrator of the program (played by Beat Takeshi9), is a bad man, certainly, for the many transgressions he commits, but he does not commit evil just for the sake of committing evil. He, like the children, is legitimately confused about the state of the world. In one of the film’s first scenes, we see that, when he was their teacher, the class took a group ditch day in defiance, and one of the students even stabs Kitano in the leg for no clear reason. Even Kitano’s own daughter hates him.

Kitano’s confusion leads him to the Battle Royale program, where he, like Beat Takeshi’s character in Hana-bi, commits terrible transgressions in the hopes that he may find a measure of transcendence. He is searching, as we learn during the film’s climatic stand off, for evidence of innocence surviving through trauma – a spark of purity among the youths he so despises. He believes this evidence exists inside Noriko Nakagawa, the one student who showed him kindness. “The only one worth dying with would be you, Nakagawa,” Kitano tells her after unveiling a painting (created, like the ones in Hana-bi, by Kitano himself) that places Noriko above graphic illustrations of carnage, as if she is a divine, transcendent deity. “If I had to choose one of you, it would have to be you, Nakagawa.” He has assigned her the role of the ‘innocent’ – indeed, she is the only survivor at this point who has not killed – and theorizes that if Noriko can survive this conflict with her innocence in tact, then maybe there is hope that this broken world can find transcendence.

He is willing to stake his life on it. As Noriko holds a gun trained on him, Kitano urges her to fire, knowing that if she does, his thesis will be proven wrong. “Go ahead, shoot. You can do it. Nakagawa, you can do it.” But Shuya, who knows as well as Kitano that Noriko’s innocence is worth protecting, fires instead, and through this final transgression, thus completes his transcendence. He is not innocent, but he has the means to defend innocence, as he just has, and maybe, just maybe, the world can change if he and Noriko go on living, complementing each other as they have all along, gradually rising higher and higher above the horror they have seen.

Yet the greatest and most significant piece of transcendence in Battle Royale does not come here, but in the very last scene of the film10. It is a dream sequence, one Noriko glimpsed herself earlier on, but it belongs to no particular character. In it, Noriko and Kitano walk along a riverside in the city, and Noriko tells Kitano a secret: “The knife that stabbed you, to tell you the truth, I keep it in my desk at home. When I picked it up, I wasn’t sure what to do with it. But now, for some reason, I really treasure it. That’s our secret. Just between us.”

Kitano is visibly wounded and confused by this revelation. Not only does this seem to betray the friendship he thought he shared with Noriko, but it undermines her innocence, for she ‘treasures’ something violent. Now he cannot place is faith in an ethereal notion of ‘innocence.’ The golden standard he spent the film searching for is a falsehood, and this leaves him with no choice but to start a dialogue.

“Tell me, Nakagawa,” he says. “In this moment, what should an adult say to a kid?”

This simple yet profound note is where Fukasaku leaves us, not just in this film, but in the entirety of his long career (this would be his last film). The final scene urges adults to begin a meaningful conversation with the youth, to reach across the generation gap, discover what each side holds truly meaningful, and find a way to finally understand one another. These limits that shackle us from each other must be transcended, because otherwise, our fear will lead us to terrors like the Battle Royale.

It is significant that this conclusion is shown as a dream, for while the pluralistic nature of Battle Royale quite clearly leads to this major transcendental revelation – it is built upon so many individual character and thematic elements that come before – it is a moment of transcendence too large for any one character to experience. It creates a new transcendental momentum, one that points towards a place of societal healing, and thus exists outside the confines of the film. This momentum, resolving and supplanting the one that propelled the film up to now, shall be carried by the audience out into the real world, lingering long after the final frame has projected. In this way, Battle Royale, like Hana-bi, can be considered a work of true cinematic transcendence.

Onwards!

Life is filled with trauma. There is no denying this fact. Transcendence, as a concept, is meaningless if there is not something to ‘rise above’ in the first place. Because Takeshi Kitano and Kinji Fukasaku both understand this truth, they are capable of making films that connect deeply with the human spirit, and achieve universal relevance in their work by drawing upon their own personal trauma. These are supremely honest works of art, ones that do not sugarcoat reality, but recognize that good and evil, violence and nature, and transgression and transcendence are all inextricably linked, and cannot be ignored. Above all else, these films encourage us to encounter what we find dark or confusing, for only by comprehending that which is bad can we truly appreciate that which is transcendent.

Endnotes

1 – These are the original Japanese titles of both films, and are how they shall be referred to throughout. Battle Royale is an English title (and is presented as such in the film), for the phrase directly derives from the English-language wrestling term. It is often erroneously written out in English as Batoru Rowaiaru, a romanization of the katakana transliteration provided under the film’s title for Japanese audiences unfamiliar with the roman alphabet (バトルロワイアル). This is an inane and incorrect way to write the title, as the title is clearly intended to be written and said in English (not uncommon in contemporary Japanese cinema).

2 - English-language quotes from the film Hana-bi in this section are taken from the 2012 Mongkol Cinema DVD English subtitle track, translated by Jeanette Amano.

3 - All Kanji provided in this section were double-checked and researched through the Denshi Jisho online Japanese dictionary, a very thorough resource on the Japanese writing system for English speakers. See Works Cited page for details.

4 - The performance alias of Takeshi Kitano. “Beat Takeshi” is the name Kitano uses when he acts, whether in his films or someone else’s. It originated during his days as a manzai comedian performing in a two-person act, ‘The Two Beats’ (the other man was ‘Beat’ Kiyoshi). When the duo dissolved, Kitano kept the name, as he was already famous for it. The thesis of Casio Abe’s landmark Kitano text, Beat Takeshi vs. Takeshi Kitano, is that Kitano kept his ‘actor’ and ‘director’ personas separate by name as a critique of television culture and a commentary on the nature of his own body, and of the pliable concept of the ‘body’ in general. This most certainly comes into play in Hana-bi, as it is the first time Kitano appeared on film following his motorcycle crash, and therefore serves, in part, as an exploration of how the ‘Beat Takeshi’ body audiences were familiar with had been transfigured.

5 - A major and essential symbolic element of nearly all Kitano films. Kitano is consistently fascinated by death in all his works, not out of morbidity, but from the sense of quiet enormity death projects when contrasted for life. The ocean, Kitano’s films seem to suggest, contains this same quiet enormity, for it is beyond the scale of human comprehension and exists beyond all human life. It is effectively ‘infinite’ to our infinitesimal gaze, and placing action or characters near the ocean therefore puts them (and the mind of the viewer) in close proximity to a profound sense of how life, death, and everything in between are connected and dwarfed by time and nature. This is clearly essential to Hana-bi as well.

6 – The depiction of which, a stirring sequence built on stillness, silence, and quiet tension, is among the most stunningly confident and controlled pieces of modern filmmaking, and an unforgettable highlight of Kitano’s filmography.

7 - English-language quotes from the film Battle Royale in this section are taken from the 2011 Anchor Bay Blu-Ray English subtitle track; translator not credited.

8 - The statement was initially circulated in the English-speaking world through the various international (and sometimes illicit) DVD releases Battle Royale received, and from what I have gathered over the years, it was included on the original Japanese DVD release (from which most of the Battle Royale bootlegs were copied and then translated), and is sourced from contemporary press notes. The citation I have made in this essay’s bibliography refers to the most easily accessible and often quoted online translation of the statement, kept by the Internet Archive from the early 2000s.

9 - One of the most interesting connections between Hana-bi and Battle Royale is that they both star Beat Takeshi, and that these are arguably his two greatest dramatic performances to date.

10 - Of the 2001 ‘Special Edition,’ that is. After the film’s initial box office success, Fukasaku added several new sequences to the film for a theatrical re-release, almost all of them centered around flashbacks or dreams. The scene discussed here is glimpsed silently and briefly as a dream of Noriko’s in the theatrical cut, and is brought back in full, with sound, to end the Special Edition, after the main action has concluded. This version of the film is the one most prominently known to audiences outside of Japan, as it was the one widely circulated on bootleg releases before official DVD and Blu-Ray sets were issued in the United Kingdom and the United States in 2010 and 2011, respectively, making the theatrical cut easily available for the first time.

Bibliography

Abe, Casio. Beat Takeshi Vs. Takeshi Kitano. Trans. William O. Gardner and Takeo Hori. New

York: Kaya Press, 2004. Print.

Ahlström, Kim, and Jim Breen. Denshi Jisho. Web. 20 April 2013. <www.jisho.org.>

Battle Royale: Special Version. Dir. Kinji Fukasaku. Perf. Tatsuya Fujiwara, Aki Maeda, Taro

Yamamoto, Takeshi Kitano. Toei Company, 2001. Blu-Ray.

Fukasaku, Kinji. “Director’s Statement.” Internet Archive, 20 Dec. 2001. Web. 20 April 2013

Fukasaku, Kinji. “Living Through War: A Conversation With Filmmaker Kinji Fukasaku.”

Trans. Nate Collins. Battle Royale: The Novel. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2009. Print.

Hana-bi. Dir. Takeshi Kitano. Perf. Beat Takeshi, Ren Osugi, Kayoko Kishimoto, Susumu

Terajima. Nippon Herald Films, 1997. DVD.

McDonald, Keiko. “Kinji Fukasaku: An Introduction.” Film Criticism. Volume 8. Issue 1

(1983): Pp. 20-32. Print.

“Transcend.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Inc., n.d. Web. 20 April 2013.

Read All ‘Essay Day’ Entries Here:

#1 – Heart of the Tramp: Charlie Chaplin’s Ethic of Dignity

#2 – Absolute Contingencies: The Double Life of Veronique, Under the Skin, Proteus, and the Wonder of Internalizing Art

#3 - Louis Malle’s Damage, Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, and the Circularity of Transgressive Energy

#4 – Fire Trails on Silver Nights: Representing Wonder and Balance in Three Works by Luis Buñuel, Bruce Springsteen & Steven Millhauser

#5 – Bond on Bond: Quantum of Solace and the Elusive Case of the Bondian Ideal

#6 – Is Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan Documentary Not?

#7 – Realism and Character Study in Agnes Varda’s Cleo From 5 to 7

#8 – Maya Deren in 3D! Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, and Cinematic Visions from the Beyond

#9 – Suffering and Transcendence in Federico Fellini’s La Strada and The Dardenne Brothers’ L’Enfant

#10 – Bob Dylan, Dont Look Back, and the Reflexivity of Direction

#11 – From Book to Cinema: Adaptation and the Construction of Film Noir in The Postman Always Rings Twice

Jonathan R. Lack has been writing film and television criticism for ten years, for publications such as The Denver Post’s ‘YourHub’ and the entertainment website We Got This Covered, and is the host of The Weekly Stuff Podcast with Jonathan Lack and Sean Chapman. His first book – Fade to Lack: A Critic’s Journey Through the World of Modern Film – is now available in Paperback and on Kindle. Follow him on Twitter @JonathanLack.