Indiana Jones and the Internet’s Punching Bag - Revisiting Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

Part 4 of our week-long journey through the Indiana Jones series

Ahead of tomorrow’s release of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, I am spending the week writing about each of the first 4 films in the series, with one review going up every weekday at Noon, leading to my review of the new film on Friday. On Monday, I wrote about Raiders of the Lost Ark; on Tuesday, I covered Temple of Doom; and yesterday I dived into Last Crusade. Today, we’re finishing up the Spielberg-directed entries with 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Enjoy…

Here’s the thing about Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull: As much time as the Internet hive-mind has spent dog-piling on this movie as one of the greatest cinematic disasters of all time, that consensus was mostly manufactured after the fact by chronically-online types looking for fresh meat after picking over the carcasses of the Star Wars prequels. Upon its arrival in 2008, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was well-received. Not rapturously so; nobody insisted it was the best film in the series, but neither was there this immediate sense it was obviously the worst. It has a solid 77% on Rotten Tomatoes, if you want a sense of the critical consensus; Roger Ebert gave it three-and-a-half stars, half a star short of his maximum. Temple of Doom is a much better and more interesting film, I think, but it was absolutely more critically divisive, and prompted more debate amongst audiences – the PG-13 didn’t invent itself! – upon its release in 1984 than Crystal Skull did in 2008. Crystal Skull also grossed nearly $800 million worldwide at a time when that was still a very rare thing for movies to do; it was the year’s second-biggest success behind The Dark Knight, and it grossed $200 million more than Iron Man, the start of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which released the same month.

I definitely liked it at the time. I was regularly writing movie reviews at this point, and I saw Crystal Skullopening day with Sean Chapman, my future Weekly Stuff Podcast co-host (one of the only times we’ve gone to the movies together). The theater was packed and I distinctly remember people having a good time. My review was pretty positive. Here’s some of what I wrote back then, at the tender age of 15:

“My big worry about the movie was that, even if it was a good film by its own rights, it wouldn’t feel like an Indiana Jones adventure. The easiest way to sum up my praise for the film is that it is 100 percent an Indiana Jones film. At times, it felt like I had plucked a DVD I never knew existed out of my Indy DVD box-set, and was projecting it on the big screen. The plot, the action, the acting, the directing, and the music all reek of Indiana Jones, and it simply rocks … “Crystal Skull” is the most enjoyable experience I’ve had at the movies all year. The joy of seeing my favorite hero back on the big screen is just phenomenal … [It] ties the entire series together, filling in gaps between movies and bringing a close to some relationships. It makes for a great finale to the series, though if they make a fifth, I won’t object … Indiana Jones has trekked many miles, and the ones trekked in Crystal Skull are as fun as any that have been traversed before.”

So yes, it is a fiction, fueled by 15 years of memes and the relentless cynicism of online film spaces, that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was this widely reviled bomb that turned off audiences and killed the franchise dead. People liked this movie, even if many now have been tricked into thinking there’s nothing of value here, without going back and revisiting it for themselves. I hadn’t done that in a long time – I’ve seen the first three films multiple times in the past decade, but haven’t revisited Crystal Skull since it hit home video – and it was definitely the sequel I was most interested to revisit for this project. My thoughts are fairly settled on the previous films; Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is a movie so buried in the avalanche of memes and internet potshots that I honestly didn’t have much of a sense of my own opinion on it anymore.

After giving it another watch, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is a movie I find immensely frustrating, but not because it’s some fundamentally inept disaster tripping on rakes for two solid hours. Far from it. What disappoints me here is that it’s a movie with true pockets of greatness and a lot of deeply interesting ideas, and most of its potential melts away into dull action and awkward CGI soup in the film’s mostly lifeless second half. By the end, it is the least of the Spielberg-directed Indiana Jones sequels; but at the start, it may well be the best of them.

The first 20 minutes of this film are outstanding, full stop, without qualification. Spielberg is energized, engaged, and has a core set of big ideas that are more ambitious than anything in Last Crusade, and more thematically coherent than anything in Temple of Doom. The opening fade from the classic Paramount logo into the groundhog’s mound signals a playfulness that continues throughout this opening stretch, and as soon as “Hound Dog” kicks in on the soundtrack, you can feel Spielberg and company are invigorated by the 1950s period setting; the vehicular teasing between the hippies and the Army is a more exciting car chase than anything the film does later in the jungle. Indy himself is re-introduced with a spectacularly staged piece of showmanship – hat first, before he’s tossed to the ground from the back of a truck, stumbling to his feet and donning the hat in silhouette before turning into frame and grumbling “Russians!” – and the opening set piece in the warehouse from the end of Raiders, now revealed to be Area 51, is just delightful. It starts out as a solidly tense slow-burn, with Indy and his Soviet captors searching the labyrinth of boxes, and when the action breaks out, it’s spectacular. More than that, though, it’s smart and sly, taking one of the most iconic images of the original film and opening it up into a big arena for Indy to make a meal of, smashing cars through boxes and whipping and running his way across the rafters. It’s briefly nostalgic, and then it’s irreverent – we remember this space from the end credits of Raiders, but Indy’s never been here before, and he’s just scrambling to stay alive.

But that’s just an appetizer to the main event, which is Indy escaping to the fake town just as an A-bomb test goes off. This too is a scene concerned with iconography, in multiple directions: It’s Spielberg wielding the most famous shape of his career – the outline of Indiana Jones – against the carefully constructed image of 1950s American suburbia, of planned neighborhoods, white picket fences, and the American Dream put up for sale. All of it is, very literally, fake – an iconic fictional character running around an imitation town full of mannequins, all of which is about to be destroyed by the horribly real iconography of The Bomb.

The greatest disservice the Internet has done to Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is to reduce Indy surviving the bomb by hiding in a fridge to a crazy ‘jump the shark’ moment, instead of engaging with the actual text of the film, where it is the crucial gesture in an elaborate and sophisticated satire. The movie is not subtle that this is, ultimately, something of a joke: there’s a close-up of the words “Lead-Lined” on the fridge as Indy clambers in, and it’s revealed with absolute precision comic timing. But it also solidifies the entire sequence’s fascination with the fundamental fictions undergirding this entire era of American life. No, a fridge would not, in reality, protect Indiana Jones from a nuclear bomb; neither would ‘duck and cover,’ but that didn’t stop the American government from placating its citizens with those instructions during the Cold War. It’s the culmination of an incredibly sharp series of escalating gags, starting with Indy’s confusing, surreal encounter with the plastic ephemera of this constructed American dream, only a matter of degrees more uncanny than the real thing, which was also, of course, a fiction, one predicated on violence and exclusion. And as Indy hides in the lead-lined fridge, that violence comes back upon this plastic paradise tenfold, all of it vaporized in little more than an instant, the milquetoast smiles of the mannequins melting into abject horror. The “nuclear family” made manifest, in more ways than one.

When Indy lands and crawls out of the fridge, there are only two things left in this desolate environment: The mushroom cloud and the famous shape of Indiana Jones himself – the icon set against the ultimate image of destruction. The fictions we tell ourselves to sleep at night are unable to die, even as we simultaneously construct the very real instruments of our doom. That frame is one of the greatest images of Spielberg’s career; perhaps one of the greatest of any American film in my lifetime. It’s a sequence that merits discussion alongside the infamous “Part 8” episode of Twin Peaks: The Return, where David Lynch similarly revisits the horrible iconography of The Bomb in the latter days of his career, and approaches it through the resuscitation of his own most iconic creation, which is Twin Peaks itself. This isn’t the Indiana Jones franchise jumping the shark, but Spielberg getting more use out of this character than he had since 1981, doing something truly novel and interesting and even subversive with him. It is this movie’s lease on life.

And for a little while after the bomb goes off, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull intimates it might have enough ideas of substance on its mind to carry that energy through for the rest of the film. I like the intimations of backstory for what Indy has been up to since Last Crusade, serving heroically in the War, and how he gets swept up in the Red Scare all the same, harassed by the FBI and kicked out of his beloved University. Afterwards, Ford and Jim Broadbent, playing a new character who fills the same function as Marcus Brody, reflect on the times. “I barely recognize this country anymore,” Broadbent says. “The government’s got us seeing communists in our soup. When the hysteria reaches Academia I guess it’s time to call it a career.” Indy sits at his desk and looks at portraits of his dad and Brody, who, like their performers Sean Connery and Denholm Elliot, passed away in the time since Last Crusade. “Brutal couple of years,” he remarks. Broadbent nods along. “We seem to have reached the age where life stops giving us things and starts taking them away.” It’s a beautiful turn of phrase – and in sum, this moody little exchange took me aback. It is all much more historically engaged and politically pointed than I remembered from this film, moving on from the Nazi set-dressing of Last Crusade to the Cold War and actually feeling like it has something to say, the paranoia of the era dovetailing with Ford’s and Indy’s visible age, and the notion of feeling the world gradually slip through one’s fingers.

What really hurts about Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is that this is the movie’s last great scene; it certainly has its moments later on, and I don’t think it ever becomes abjectly horrible in the way 15 years of Internet histrionics would have you believe, but it gradually becomes less and less connected to the many compelling ideas it plants in these opening scenes. And that’s not because the movie is, ultimately, about aliens – when we actually get to the eponymous Crystal Skull, and see how this movie frames extraterrestrial life, there’s meat on those bones. The Skull itself is a terrific, evocative prop, and the hints of psychokinetic powers connected to both it and the film’s chief antagonist, Cate Blanchett’s Irina Spalko, is weird and off-kilter in exactly the right way. I want to see the Indiana Jones movie where the looming destruction of the Atomic Bomb hangs over a paranoid Cold War-era America, and an Indiana Jones on the run from the Red Scare gets embroiled in a quest about psychic, interdimensional space beings whose approach to amassing and sharing knowledge both dwarfs the scale of our problems and shines a light on how we might, in a better world, solve them. I think Indiana Jones is capable of something like that, and I know Steven Spielberg could direct the hell out of it.

The problem is that all involved chickened out.

The behind-the-scenes wrangling on Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is well documented, and the fact is that while Spielberg and Ford were content to let the character lie dormant throughout the 90s, George Lucas spent years chipping away at multiple drafts of a screenplay that would bring Indiana Jones into the 1950s, and send him on an adventure inspired by sci-fi B-movies of the era, complete with honest-to-god space aliens. He put it on ice when the Star Wars prequels went into production, but dusted it off in the 2000s when Spielberg and Ford were more amenable to returning. I think Lucas’ general idea was right on the money. The only reason to do more Indiana Jones is if you have a truly new direction for the character, and Lucas’ pitch both honored the real-world passage of time and made use of the possibilities opened by shifting the story to the 1950s. Raiders of the Lost Ark was inspired by adventure film serials; why not have a sequel that drew from a different, but equally pulpy, vein of American pop culture ephemera?

The problem is that Ford and especially Spielberg were uncomfortable with the aliens. Spielberg, in particular, didn’t want to retread ground he’d already covered in films like Close Encounters or E.T., and he and Ford favored a more traditional Indiana Jones story. The film went through countless drafts as they tried to find some kind of middle ground approach, and while Lucas finally won out in some ways – the finished film is set in the 50s, has Soviet antagonists instead of Nazis, and technically does have aliens – the identity crisis is readily apparent in the body of the film. Every time Kingdom of the Crystal Skull broaches its most outlandish (and, not coincidentally, most ambitious) ideas, it does so with a notable timidity; Irina Spalko has psychic powers, but we don’t call them that, and we only see her briefly call upon them twice, to seemingly no avail. There are aliens, but we cut away very fast from the carcass stolen from Area 51 when we finally see it, and the movie stops dead in its tracks twice for John Hurt to turn to the audience and explain these aren’t actually space aliens, but interdimensional beings (they come from the “space between spaces,” you see – Spielberg wouldn’t do the movie unless Lucas relented on this point).

If you think space aliens are utterly anathema to the spirit of Indiana Jones, I’m not going to argue with you; I disagree – this series has engaged in fantasy every bit as ‘out there,’ if not moreso, than the idea of extraterrestrial life, and its pulp serial roots dovetail very naturally with the 50s sci-fi B-movies Lucas wanted to pull from – but to each their own. What I will point out is that, as it stands, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is neither fish nor fowl. If you don’t want aliens in Indiana Jones, they’re technically here, and the briefness and timidity with which they’re approached makes their presence all the more jarring. If you, like me, wanted something new from this franchise, and are on board with it steering into sci-fi as the next frontier of its pulpy adventures, what this film settles on feels mostly half-assed.

The rhythm Kingdom of the Crystal Skull ultimately settles into is a pretty simple imitation of Last Crusade, which was itself a dumbed-down imitation of Raiders. Indy hears about a MacGuffin a colleague was obsessed with, and goes adventuring through tombs and getting into big elaborate chases going after it. Some of it is executed well – I like the exploration of Francisco de Orellana’s tomb, which is a fantastic set, and the uncovering of the skull itself – some of it is executed terribly – more on that in a bit – but the only parts that truly stand out are those brief instants when the movie threatens to be about psychokinesis or space aliens, and you perk up in your seat, either hoping or dreading that the movie will leap off the deep end. It doesn’t, and the end result is a very milquetoast version of the Indiana Jones formula that probably won’t offend any honest viewer, but won’t excite or inspire them either. “Same old, same old,” Indy grumbles when he and his companions find themselves held at gunpoint again; he might as well be watching from the audience.

The big new idea the film actually invests in is Mutt Williams, the son Indy never knew he had, and I don’t think it’s a bad idea on paper. Thematically, Indy learning he has a son, and a new relationship to foster, is a good rejoinder to the “life stops giving” idea expressed at the outset, and having a newcomer on this adventure makes for a potentially effective audience surrogate figure, either for new viewers who weren’t there in the 80s, or to allow older viewers a chance to see Indy anew.

The problem is he’s played by Shia LaBeouf.

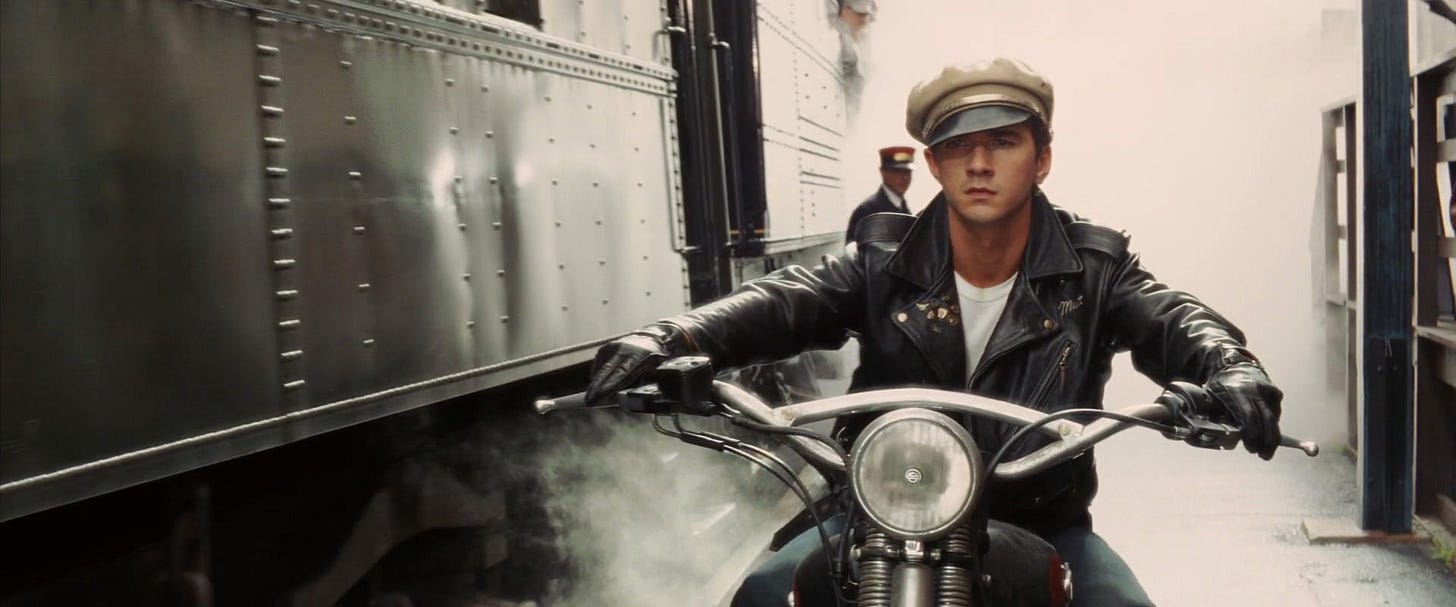

I don’t quite know how to accurately describe the kneejerk feeling of cringe that lands when Shia motorcycles into this movie, a living, breathing anachronism in every way. Some actors, like Harrison Ford, can be plopped in just about any period, historical or fictional – WWII, the old West, a dystopian future, outer space, etc. – and remain believable and compelling. Shia LaBeouf is not one of those actors. He is too of his moment, too obviously a creature of the mid-2000s in the way he speaks and holds himself; watching the film in 2023, that quality is compounded by the knowledge that his stardom was short-lived and that he flamed out spectacularly in every possible way – professionally, personally, and morally. For reasons both within and without this movie’s control, its most prominent co-star is an actor who will forever be locked to one specific moment in time – that brief period in the mid-to-late aughts when Spielberg, inexplicably obsessed with this kid, got him cast in this and Transformers and several other big productions – and never comes close to blending into the movie around him. He makes this film feel more painfully dated than any analogue special effect in the first three films ever could.

Harrison Ford is actually really effective in this one, moreso than I remembered, charismatic and funny and engaged from start to finish, but even taking Shia out of the picture, the supporting cast around him is awfully thin. There’s nothing wrong with Ray Winstone in principle, but what he’s doing here is just a ridiculously broad caricature, a cockney n’er-do-well we never believe, for a second, could actually have been one of Indy’s closest and most trusted allies. Karen Allen returns as Marion, which is a great idea in the abstract, but the script gives her almost literally nothing to do; she’s along for the ride, but as baggage, not as a character. Allen obviously hasn’t lost a step – her smile when we first see her is infectious, a dead ringer for the energy she brought to Raiders, and she’s constantly sparking little bits of joy in the background – but her most substantive scene is a big argument with Indy about what a coward he was when he got cold feet before their wedding. At the end, they get married anyway, without any on-screen reconciliation, and no conversation about Indy being kept out of his son’s life for 20 years. It’s weird.

I do enjoy Cate Blanchett here. She knows exactly what she’s doing – a ridiculous accent, weird bob-cut hair, and crazy telekinetic powers, all approached with absolute gusto. But Blanchett is the rare actor with the kind of inherent gravitas to keep one foot in the film’s reality, and make it all seem plausible within this particular pulpy register. She’s great, and absolutely in line with Ronald Lacey in Raiders or Julian Glover in Last Crusade.

The film’s big central set-piece, a chase in the Amazon, is the nadir of the franchise so far, and it’s mostly a failure of special effects and visual design. The comparable sequences in the other films – the truck chase in Raiders, the tank chase in Last Crusade – happen outside on location in tangible spaces, where the stunt work feels live, real, and even a little dangerous. When Indy goes out the windshield and under the truck in Raiders, it’s remarkable in part because it’s a real truck moving on a real road, with a real stunt person doing it all before our eyes. Here, we have the actors on real vehicles on partial sets mostly filled in with CGI, and a lot of very iffy compositing that makes the actors feel fundamentally disconnected from the spaces they’re in. The choreography itself is a repetitive shadow of the dynamics of those earlier chases, but even in its more inspired moments, the effects simply don’t pan out. Janusz Kaminski was Spielberg’s regular DP at this point, where Douglas Slocombe had shot the older Indy films, and his style of cooler colors and overexposed highlights does not mix well with the effects; the colors, which are somehow both undersaturated and overbaked, make even the physical elements of the scene look fake. This is genuinely one of the worst-looking scenes of Spielberg’s career, the most uncomfortable he’s ever felt with special effects. Compare this to the mine cart chase in Temple of Doom, which is just nonstop virtuosity, while also being a primarily studio-bound, effects-driven sequence, his comfort with using plates, optical printing, mattes, and other tricks making for a supremely confident sequence. This feels like a filmmaker out of his depth, which is probably the only time I’ve ever written those words about Steven Spielberg.

And yes, Mutt swinging through the jungle on vines like a monkey is stupid, though honestly, I think my real problem there isn’t the idea or even the effects, but the Shia LaBeouf of it all. He also gets into a swordfight with Cate Blanchett while suspended across two cars, and that’s another moment that has a germ of a good set-piece in it, but the problem is the same one that killed whole swaths of the Transformers films, which is that Shia always looks and acts like a putz, and certainly never a believable action hero. Thank God Harrison Ford takes the hat back at the end when Shia briefly picks it up – I can’t imagine an actor less worthy of taking the mantle.

What is so disappointing about this film, ultimately, is how disengaged its second half is from the ideas of its first, divorcing itself from the particulars of its period setting, failing to follow through on themes suggested early on, and being persistently afraid to embrace the most interesting parts of itself. As rough as much of the VFX work is, I really do love the image near the end of the flying saucer coming up out of the Mayan ruins, with Indy down in the corner of the frame, a giant crater left in its wake that gets filled in by the rushing falls. It’s an incredible image, and a neat counterpoint to the Atomic Bomb on the other end of the film. Destruction and creation, and creation within destruction, with Indiana Jones as audience to all of it. I like the way it rhymes. I wish I could love it, as I might if this film really followed through on itself.

But again, for whatever flaws Kingdom of the Crystal Skull has – and they are numerous – it at least opens with an ambition and vision I find admirable, even if that only lasts about 20 minutes. A low bar, perhaps, but the Indiana Jones sequels are a weird set of films. Temple of Doom has the best filmmaking and set pieces, Last Crusade is the most all-around competent and palatable, and Crystal Skull has the most untapped potential. I don’t know how you grade them against each other. Temple of Doom is the most compelling and interesting, I think, not only for its craftsmanship, but for all the unresolved (and maybe unresolvable) emotions and contradictions swirling around in its angry, bitter heart. It is a film that demands to be grappled with, that grabs you by the collar and forces a reaction, while Last Crusade is content to simply entertain, and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull fizzles out. Ultimately, this isn’t so much a coherent franchise as one titanic masterpiece standing tall on an island of its own, followed by a series of increasingly wayward attempts to touch the sun one more time.

Will Dial of Destiny finally be the one that does it? Probably not, but I’m going to find out anyway. Come back tomorrow for my thoughts on the franchise’s latest attempt to strap on wax wings and go flying towards the stars.

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our sister series about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Explore our archives and subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all podcasting platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com