Indiana Jones and the Nightmare Factory – Revisiting Temple of Doom

Part 2 of our week-long journey through the Indiana Jones series

Ahead of the release of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny this Friday, I am going to spend the week writing about each of the first 4 films in the series, with one review going up every weekday at Noon, leading to my review of the new film on Friday. Yesterday, I wrote about Raiders of the Lost Ark, and today, we’re continuing with 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Enjoy…

If Raiders of the Lost Ark can be tough to write about because of how many avenues of brilliance it offers to unpack, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is a challenge because its own pockets of virtuosity – and there are many – exist alongside so much ugliness, misery, awkward narrative construction, and outright racism. There is both bitter, resentful fury simmering under this movie’s surface, ready to lash out at a moment’s notice, and joyous acts of inspired creation; it can turn on a dime, and the whiplash is frequently shocking.

The film, like each of the Indiana Jones movies, has a reputation that precedes it, of course. A shockingly dark sequel so violent that it, along with the Spielberg-produced Gremlins from the same year, prompted the invention of the PG-13 rating. A movie that takes such a sharp tonal left-turn from its beloved predecessor that it practically ensures it will be a love-it-or-hate-it proposition, and that even creative leads on the film disagree on. Spielberg has spoken poorly of it, and both he and George Lucas have attributed its darkness to tumult in their respective personal lives, something you can definitely feel in the finished product. Still, the film casts a long pop culture shadow, many of its images having proven, for better or worse, indelible, and certain scenes having been strip-mined for parts; the outstanding mine-cart chase near the end, the preeminent theme-park-ride-as-action-sequence, was borrowed wholesale by Resident Evil 4, in both its original 2005 version and this year’s remake, which incorporated even more ‘mechanics’ from Temple of Doom.

I have ping-ponged throughout my life between loving Temple of Doom’s audacity and finding its grim brutality overbearing and off-putting. This is, essentially, a horror film, particularly in its second half, where we see hearts ripped out of chests and scores of children forced into back-breaking labor. It is a walking nightmare – haunting, striking, and undeniably effective, but debatably effective as an Indiana Jones sequel. I doubt very much anyone walked out of Raiders of the Lost Ark imagining a follow-up where Indy is force-fed blood from a decayed human skull, tortured via a voodoo doll held over flames, and brutally struck over and over with his own whip. On the one hand, I genuinely like the idea of a sequel giving the audience something other than they expect or think they want. A Raiders sequel eschewing the adventure-movie shape of its predecessor and instead going for outright horror is not a bad idea, and Spielberg brings the receipts when it comes to scares. Yet the film is so relentless in its bleakness, bordering on nihilistic, and without the sense of clarity in character or theme you would need to truly pull this off. It often feels miserable for misery’s sake, Lucas and Spielberg offloading the misery of their own lives to the audience via this film, which increasingly feels like an act of cinematic self-flagellation as it moves on, a strange act of penance.

That so much of the film’s horror is built on abject racism doesn’t help, and should not go unremarked upon. The film’s use of India is awash in gross oriental tropes: the leering way it looks at poverty, at food, at the harshness of nature; its mysticism-laden representation of local customs and peoples, who are defined entirely through difference and mystery; the touristy way it appreciates elephants and wildlife and palaces; the positioning of Indiana Jones as a very literal white savior, falling from the sky to save wretched villagers from a dark ancient religion; and most strikingly, the disgusting humor built around a wholly constructed, fictional ‘savagery.’ The infamous dinner scene at the palace, where Indy, Willie, and Short Round are served snakes (stuffed with more snakes), beetles, and chilled Monkey’s brains, is a vile and abhorrent display of bigotry, a horror/comedy scene predicated on the supposedly repulsive customs of dark-sinned foreigners, which this movie has entirely made up. There is no excusing it. Willie Scott’s intonations of “you’re not one of them!” to a possessed Indy as he menaces her down in the temple make the point all too clear: this is a statement of racial hierarchy more than a call to Indy’s fundamental nature, which Willie, barely having met the man, would know nothing about. He is white, and therefore he should not be participating in this savage, violent ritual – only the bad, scary brown people would torment a white lady like this. The set-piece that ensues is one of brown bodies trying to burn a white woman alive, with the heroic white man and his Asian servant boy trying to protect her skin from the fire. It is a grotesque spectacle straight out of 1933’s Kong Kong, but made half a century later.

Of course, it does not help that Willie Scott herself is one of our protagonists, and that even when she is not being threatened with fire, she is constantly embodying every racist impulse a white person could display while trapsing through another culture, while also being herself a wildly sexist anachronism. Willie is the worst version of the vain, damsel-in-distress bimbo gold digger character, complaining about hang nails when lives are on the line, and perfuming elephants when she finds their smell unpleasant. She is the opposite, in every way, of Marion Ravenwood from Raiders of the Lost Ark: not Indiana Jones’ equal, not a partner to respect and learn from, but his contrast, weak and cowardly and selfish and intolerant, existing to make Indy look better by comparison, but never to propel him to become better. To be fairer than the film perhaps deserves, the intent is obviously to have Willie act as a comic foil, a joke, but it doesn’t work – the character as written and directed is so over-the-top that it ultimately feels like an earnest, unironic deployment of so many awful stereotypes. I don’t think any of this is actress Kate Capshaw’s fault – who could have made this work? – and she herself has shown plenty of self-awareness about the part’s limitations in the years since. She and Spielberg met on this film and later married, a union that’s lasted for over thirty years, so at least some personal good came out of it.

The best part of the movie, perhaps the most lasting piece of the film’s strange legacy, is surely Short Round, Indy’s child sidekick, played by now-Oscar winner Ke Huy Quan (isn’t that fun to write?) in his feature debut. And even then, this aspect of the film is complicated. Short Round, from the name on down, is a stereotype, a caricature, the kind of restrictive, racially-determinative role that eventually drove Quan away from acting for decades, when he found this was the only kind of thing Hollywood wanted from him. But it is also a beautiful, passionate piece of child acting, infectiously joyful and palpably human. Spielberg directed E.T. between Raiders and Temple of Doom, and he knows better than most filmmakers how to give children the space to be expressive and authentic on screen, even in a role like this which is heightened and sensationalized. Quan and Harrison Ford form a truly lovely acting duet here, and while Ford spends several chunks of the film on autopilot, he is fully engaged when acting opposite Quan; their chemistry is human and moving, and their relationship is the film’s single true vein of warmth. The character as written is symptomatic of some of the film’s worst tendencies, but on screen, he is the film’s heart and soul. In the depths of the film’s impossibly dark second half, Short Round isn’t just Indiana Jones’ redeemer, waking him up from the spell: he’s the closest the film comes to actually redeeming itself.

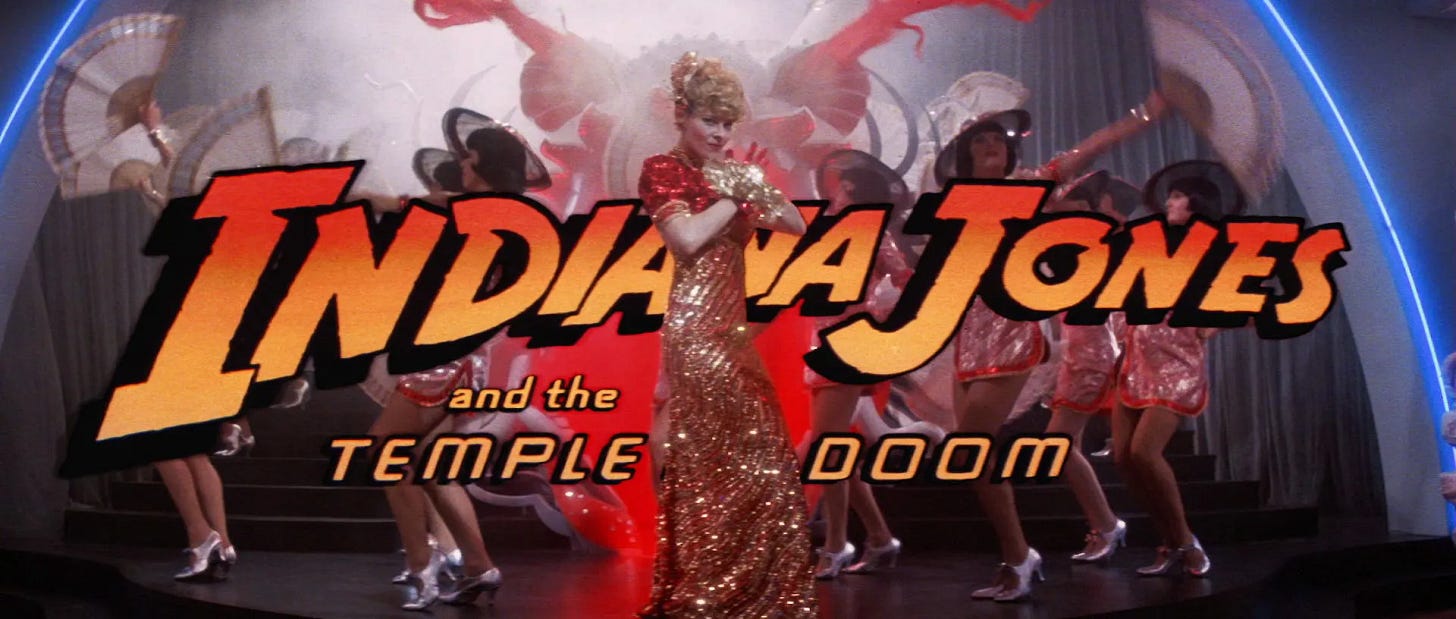

Temple of Doom does, of course, start out quite strong. The Paramount logo match-fades into the carving of a mountain on a gong, and a whip pan brings us over to the stage where Capshaw dances out of the mouth of a dragon to sing “Anything Goes,” her body covering up part of the film’s title as it appears. It is a playful, lithe, grand piece of showmanship to kick things off. That Spielberg was destined to eventually direct one of the most technically accomplished movie musicals of all time – 2021’s West Side Story – was written in the stars from the moment he put this together. When we cut into the imagined Busby Berkely space for a full-on 40s revue-style group tap dance, you can practically hear the director cackling. There is real joy at work here, and it fully extends into the opening action set-piece at Club Obi-Wan, which is damn near as good as anything in Raiders, every bit as confident in its genre bonafides and stylistic throwbacks. The costumes and production design – which are consistently the star of the show this time around – are just extraordinary, and once the action kicks off, it is so fluidly choreographed and imaginatively put together, all scored to a big orchestral arrangement of “Anything Goes,” Indy and the gangsters now joining together for a big choreographed musical number of their own. There are so many clever elements at play, like the antidote Indy is chasing throughout the sequence, paired with Willy going after the diamond, while around them is so much playful excess, like the shower of balloons impeding their progress, or Indy hiding from Tommy-gun fire by running behind the rolling gong. It’s an action set piece put together with the timing and enthusiasm of musical theater, and it’s one of the best scenes of Spielberg’s career (though even here we get a sense of the mean, brutal streak the film will have – Indy impaling one of Lao Che’s men with a fiery meat skewer is a graphic, grisly portent of things to come).

The good times keep rolling throughout this opening stretch, with the introduction of Short Round, the car chase through Shanghai, and the action on the plane, culminating in a ridiculous climax – Indy and company survive a drop from the plane all the way to the ground with just an inflatable raft – that makes all the consternation over ‘nuking the Fridge’ in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull feel extremely silly. Really, Temple of Doom is on fire through these first twenty minutes; the problems set in once we arrive in India, and it becomes clear nothing in this excellent opening section has anything to do with the movie to follow.

The plotting here is just so much more scattershot than the impeccably tight clockwork craftsmanship of Raiders. In the first film, once Indy is airborne, we already know the shape of this movie and the goal of the journey; the character is highly motivated and will remain so until the end. Here, Indy is lost and aimless, a victim of fate who stumbles into the plot, the entire story predicated on random encounter and happenstance. There is the thinly-developed motivation of the impoverished village Indy is asked to help by investigating Pankot Palace, but the script confuses itself by introducing the secondary motivation of “fortune and glory” after Indy has already met with and empathized with these people, robbing this film of the tension, active in Raiders, that maybe Indy will give into his baser impulses and do the wrong, selfish thing in the end. Even then, once Indy arrives in Pankot, there is no proactiveness on his part; he stumbles into the eponymous Temple during a nighttime argument with Willie after foiling an assassin. Temple of Doom lacks the teachable, elegant three-act structuring of the first film; its structure is episodic and almost (but not quite) dreamlike, eventually coalescing into the full-on nightmare that is the film’s brutal second half. Of course, in this way, it is entirely possible that Temple of Doom is in fact more faithful to the movie serial roots of the series than Raiders was; these kinds of multi-part cliffhanger-driven adventures were much less cohesive than Raiders of the Lost Ark, and also, frequently, a lot more racist. On both counts, Temple of Doom might be the ‘truer’ throwback.

Speaking of the nighttime antics that lead to the accidental discovery of the temple, I was struck this time by just how flaccid the screwball comedy back-and-forth between Indy and Willie is, all their supposed ‘sexual tension’ delivered through terrible innuendo-driven dialogue. If it works, it’s only because Harrison Ford was at peak hotness, and has a smoldering sexuality undiminished by time. I often use a clip from this film in one of my classes, and last time I did so, I turned the lights back up to notice a group of girls in the back of the room having a laugh about how ludicrously hot Ford is here; I had difficulty getting class back on track after that – one must be careful about unleashing this much raw movie star charisma in a classroom. In any case, the biggest problem is that Ford and Capshaw have no shred of chemistry here; that this film came smack in the middle of a decade where Ford had all kinds of fiery, smoldering chemistry with co-stars, from Carrie Fisher to Sean Young, makes it stand out all the more.

The Temple of Doom itself is, of course, an all-time great movie set, an absolute coup of color and texture and lighting. Here is a reference only dyed-in-the-wool Colorado natives will get, but the set feels like the nightmare a child would have after visiting Black Bart’s Cave at Casa Bonita at slightly too young an age; it is at once fake and chintzy, but also terrifying and tactile. And it is the locus point of much of the film’s ugliness. The horrific ritual Indy and company witness there is one of the most memorable, effective, genuinely terrifying spectacles ever staged on film. It is so brutal and over the top – a man’s still-beating heart ripped from his chest before he is lowered into flames and burned alive before our eyes – and it is all staged with masterful showmanship. It is a nasty, harsh push into the miserable suffering that characterizes the film’s second half, sensational and unforgettable, and also profoundly racist, a spectacle of (invented, imagined) oriental savagery. It is an arresting piece of filmmaking – but to what end, and at whose expense? That is the question, and one Temple of Doom has no good answer for.

There is no easy, pithy way to summarize one’s reaction to this film. Raiders of the Lost Ark was and is one of the greatest films of all time.Temple of Doom is not, but it may be one of the most memorable, for reasons both very good and very, very bad. It is audacious and ambitious, a sequel you could not possibly accuse of ‘playing it safe,’ but that audacity and ambition is comingled with clumsiness and cruelty. It introduced us to an actor in Ke Huy Quan who, in his recent return to acting, has become beloved and celebrated anew, but it also shows off all the reasons why Hollywood drove him behind the camera and away from the limelight for so many years. The film showcases Spielberg and Lucas at their best and at their worst, and necessarily complicates the easy auteur narratives we tell ourselves; good directors can, of course, go wrong, and they can go wrong while still being skillful filmmakers, just as a movie can be both brilliantly made and offensively ignorant. People are complex, and so are films; few more so than Temple of Doom.

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our sister series about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Explore our archives and subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all podcasting platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com