Jonathan Lack's Top 10 Films of 2021

2021 was yet another terrible year for the world, but it turned out to be one of the greatest years for cinema in my lifetime. The last time I felt this strongly about a year’s worth of movies was 2014 – and before that, 2007, and 2001. Every six or seven years, it seems, we get one of these remarkable years, a convergence of established masters at the height of their craft and bold new voices establishing lasting legacies, with unexpected pleasures coming at us from all directions.

Except Hollywood. Hollywood’s mainstream wide releases were mostly really bad this year, fueled in part by a near-total creative collapse of the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s increasingly obnoxious project (Shang-Chi was the lone theatrical exception). There are a few notable standouts from the big studios, though none of the wide releases that made it onto my Top 20 did particularly well at the US box office. But as has become increasingly clear in recent years, if you’re just focusing on what Hollywood is pumping into the multiplex, you’re doing it wrong. Cinema is changing, in access and distribution and many other ways, and it doesn’t take that much digging to find gems, especially in a year as wildly rich as 2021.

I loved so many films this year so passionately that in addition to the main Top 10, we’ve got an additional 10 runners-up, bringing us to a nice even Top 20, and then five extra ‘leftovers’ I would have felt bad ignoring, so I guess it’s kind of a Top 25. #20-11 have paragraph-length capsule statements, but for the Top 10, I went all out, penning either a mini-review or a short essay for each. That means this is one of the longest pieces I’ve ever published. But the movies this year deserved it, and since I didn’t get to write many public-facing pieces on film this year, I owed it to myself to spend some time writing about all these works that meant so much to me.

The ground rules here are simple: A “2021 movie” means a film that made its commercial debut in the United States in 2021, theatrically or on streaming. Some of these films will be listed as 2020 if you look them up elsewhere, because of festival or overseas debuts, but this is how they come to count as 2021 for the purposes of this list. I also decided, for the sake of simplicity, to ignore the films that technically got commercial releases in 2021, but counted for the 2020 Oscars (films like Nomadland or Judas and the Black Messiah), because it’s tenuous and unclear where or when to count those, and it feels like they belong to last year’s cultural conversation.

Ok then. Deep breath. Here we go.

(And if you love my voice or just hate reading, you can click on the YouTube video at the top of this page to listen to the audio version of this article, with me reading all this text).

Starting with the leftovers and honorable mentions after the jump…

Part I:

Leftovers

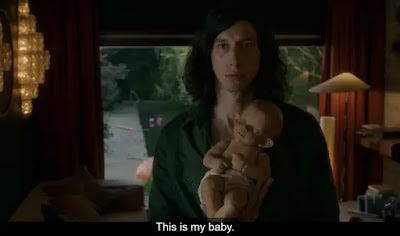

Baby Annette will haunt my dreams forever.

There were five films that finished outside the top 20 for me that I wanted to quickly mention here, in no particular order: Candyman (US, Dir. Nia DaCosta) pulses with raw filmmaking talent and great visual and thematic ideas; Nobody (US, Dir. Ilya Naishuller) turned Bob Odenkirk into a credible action star, in this terrific little shoot-em-up yarn from the writer of John Wick that absolutely belongs on the shelf next to that modern genre classic; Godzilla vs Kong (US, Dir. Adam Wingard) suffers from a few too many obnoxious humans, but absolutely soars when it comes to the monsters, delivering some of the year’s best and most imaginative visual effects; The Last Duel (US, Dir. Ridley Scott) is as well-made as you’d expect from a Ridley Scott period piece, but it’s also significantly smarter and more timely, a medieval ‘Time’s Up’ narrative told in the Rashomon structure, with good work by Matt Damon and Adam Driver, great work by Jodie Comer, and a kind of unforgettably out there turn by Ben Affleck; and finally, Annette (France, Dir. Leos Carax) is a movie I angrily described as a “war crime” back in August, finding myself viscerally rejecting almost everything about it…until I realized I haven’t been able to get the damn thing – or its kinda bad, kinda wonderful songs by Sparks – out of my head for 6 months. Do I actually like it? I have no idea. Have I spent way too much time mulling it over to honestly leave it out of this year-end retrospective? Yes. Yes I have.

Part II:

Honorable Mentions (#20 - #11)

Yes, Titane does in fact feature a woman-on-car sex scene

20. Titane (France, Dir. Julia Ducournau) is a deeply brilliant film I will never, ever be able to watch again. This thoroughly bizarre fable about a female serial killer impregnated by a car (no, not in a car, by a car) and forced to disguise and disfigure her body while on the run may be the most viscerally upsetting and disturbing film I’ve ever watched, triggering actual physical anxiety symptoms in my body I take medication to control. It’s not a film one should watch without taking content warnings seriously. ‘Body horror’ is a trigger for me in general, but Ducournau pushes those buttons harder than I’ve experienced before. Not just because the film is visually explicit (which, to be clear, it frequently is), but because it’s such a wildly skillful piece of filmmaking in making you feel every brutal moment. This is a superior piece of craftsmanship, astonishing at the level of cinematic grammar and enunciation, completely and totally singular in what it is and how it functions – and believe it or not, it’s also pretty damn funny, even if I was mostly too horrified to laugh. Much more than mere provocation, Titane is a powerful cinematic statement about the dark wonder of the body and the wrenching pain of dysmorphia. It deserves to be studied and celebrated – just not by me, because it’s good to know your limits.

19. Malignant (US, Dir. James Wan) is a film I went to see on a whim, having seen only the poster and heard some vaguely positive Twitter chatter, and it wound up being one of my favorite moviegoing experiences of the year. I didn’t find it ‘scary’ for a while – even as it’s effective affective in all sorts of ways – until the exact moment Wan pulls the rope taut, and left my jaw on the floor for the final half hour. This is a horror movie built around an idea so truly, viscerally gnarly that it borders on feeling transgressive, like some of the most messed-up imagery in the original Evid Dead – the kind of stuff you go shoot in a cabin in the woods not just because that’s what the budget allows, but because you wouldn’t be allowed to do it in proximity to polite society. James Wan is a terrifically talented filmmaker, but he’s also got several screws loose; that’s the key to why his work, from the biggest blockbusters (like Furious 7 or Aquaman) to his smaller horror experiments (the original Saw), is so damn memorable. He will always give you something to talk about, and he’ll never take you there on quite the route you’re expecting. In the case of Malignant, seeing it cold was a good choice, because this is a film that plays the audience like a fiddle so masterfully it demands to be studied. It’s one of the best uses of a ‘twist’ I’ve ever seen, playing utterly fair from start to finish while also genuinely knocking you back in your seat, with Wan making particularly interesting use of tone to keep you off kilter. This is the kind of movie I want to see again and again, but only if I can watch it with other people who haven’t seen it, so I can watch their reactions as Wan guides us towards madness.

18. Wrath of Man (US/UK, Dir. Guy Ritchie) finds Guy Ritchie doing what so many filmmakers who board the blockbuster carousel are never able to achieve: Taking the Aladdin money, jumping off the merry-go-round, and making a low-key masterwork out of the spotlight. Wrath of Man is an exquisitely controlled piece of filmmaking in service of a profoundly dark indictment of violent masculinity, a lean, sharp-as-a-razor look into the toxicity, the smallness, the isolating and self-defeating pointlessness of the anger festering inside male egos. There are no heroes, almost no one to sympathize with, and barely any warm bodies by the time the credits roll. The film looks inside the heart of a certain kind of Hollywood masculinity, archetypes you’ve seen elsewhere, sometimes in more celebratory contexts, and it sees a swirling, howling void, stalking and consuming everything in its path. Shout-outs to Jason Statham for the best performance of his career – a degree of sculpted control akin to Beat Takeshi’s work in the 90s, this furiously still surface things bounce off of – and composer Christopher Benstead for one of the most ruthlessly effective musical scores in years. It’s all low strings, menacing and calculated, like Jaws – only instead of an unseen shark in the ocean, the waters are Jason Statham’s face. The music is the blood in the film’s veins – you feel it pumping, beating, through everything.

17. In the Heights (US, Dir. Jon M. Chu) is one of the best movie musicals made in my lifetime, and it’s slightly unfortunate it had the bad luck to release the same year as Spielberg’s West Side Story, one of the greatest movie musicals of all time (more on that later!). If not, I think we’d all be talking more about what Chu and company pulled off here at year’s end, because if this isn’t quite ‘masterpiece’ caliber musical filmmaking, it’s still gorgeously, passionately constructed from top to bottom, pulsing with real electricity and brought to life by performers who can actually do the singing and dancing. Chu imbues every layer with rhythm and musicality, completely in keeping with the rhythm and character of Lin Manuel Miranda’s music, and he keeps surprising you with inspired staging and choreography and editing choices to the very end. The editing is probably a bit quicker in some scenes than I’d prefer, but it mostly works because Chu, unlike the hacks who do most modern movie musicals – *cough*Rob Marshall*cough* – isn’t desperately trying to construct simple prosceniums, but actively creating 360-degree cinematic space in every scene. You’re in the action, not just looking at it, and it makes all the difference in the world. It certainly helps that the talent on display is just off the charts. Anthony Ramos deserves to be one of the biggest stars on the planet after his performance here, but he’s also just the tip of the iceberg. What a difference it makes when you cast actual singers and dancers, versus lazy Hollywood star casting. In 2021, this wasn’t the absolute best movie musicals had to offer, but relative to the state of the genre for several decades now? It really doesn’t get much better than this.

16. What Do We See When We Look At The Sky? (Georgia, Dir. Alexandre Koberidze) is such a strange, beguiling, rambling little movie. Except it’s not really little, because it’s two-and-a-half hours long, and while its basic story is simple enough, its ideas seem to encompass both everything a story can be about, and nothing much in particular. I really wasn’t sure what my feelings were, until the film started wrapping up and I realized I was in love and didn’t want it to end. This is a hard movie to describe, especially in capsule format. It is a simple oral fairy tale set in the present day, about a man and a woman smitten with love at first sight, who wake up the next morning in entirely different bodies and are unable to recognize each other. This story is illustrated obliquely and with many digressions, as much a slice-of-life travelogue for the Georgian city of Kutaisi as it is anything else. It’s extremely playful, frequently whimsical bordering on saccharine, but always deeply sincere. “A picture book for grown-ups” is a phrase that crossed my mind near the end, and I think that’s the best way I can describe it. One of two films on this list shot in 16mm at the 1.66:1 aspect ratio – yes, please, talk dirty to me – this is the kind of movie I think I could find myself growing to love quite intensely, to the point where it may be ranked too low here. Or I may not remember it much at all in a few years. Either way, I’m immensely grateful it exists.

15. No Time to Die (UK/US, Cary Joji Fukunaga) released in the States on my 29th birthday, and it was a better present than I could have hoped to ask for. Daniel Craig, the best James Bond and the one closest to my own heart, gets the send-off his performance deserved, bowing out on a note very nearly as high as the one he came in on with 2006’s Casino Royale. It’s a deeply engaging mystery fueled by fantastic character writing, great performances, and the best direction the nearly 60-year-old franchise has ever seen. Fukunaga fully leaves his stamp with an impressively deft command of tone and a series of set pieces tailored perfectly to Craig’s physicality and specific take on the character, every action sequence a beautiful moment of synthesis between character, performance, and director. The film has an eye for visual iconography every bit as sharp as the celebrated Skyfall, but it’s even smarter and more considered in terms of visual storytelling. And most importantly of all, No Time to Die gives James Bond something he’s never had in any media, under any actor or writer, even Ian Fleming: a real, honest-to-God ending.

14. The Green Knight (US, Dir. David Lowery) proves – if movies as great as 2017’s A Ghost Story hadn’t already – that David Lowery is very much the real deal. This is bold, ambitious, provocative cinema that left me in awe. Lowery’s film is less an adaptation of the medieval poem – Sir Gawain and the Green Knight – than a reaction to it, a critique or deconstruction filtered through a dreamscape built on dream logic, all as poetic in its own cinematic way as the original text, but so defiantly singular in character and content. Dev Patel gets the best role of his career as Gawain, and Andrew Droz Palermo’s cinematography is some of the year’s best, sinister and imaginative as it unfolds like medieval paintings come to life. This is a haunted and haunting movie, dark and suggestive and as hard to shake as a vivid nightmare, and yet also so playful and light on its feet, with an ending that is either very funny or kind of horrifying – or, most likely, a little bit of both.

13. Zack Snyder’s Justice League (US, Dir. Zack Snyder) was the biggest surprise of 2021 for me, so much so that it’s the only movie I published a full written review of this year. I’ll refer you to that piece for my full thoughts, but will just say here that this the greatest and most interesting live-action superhero film in a very long time, one of the few that feels like genuine, full-throated cinema, imperfections and all. A resolutely, even stubbornly auteurist and singular production, an exercise not just in duration, but in wonder, conjuring a sensation that has so often eluded this genre since Richard Donner cracked the code with Superman in 1978. It feels more akin to the silent epics of the 1920s than it does the Marvel assembly line of the 2010s, a real epic about mythical characters wandering through a broken, fallen world, and finding communion in each other as the only way of starting to repair themselves and their surroundings. The Snyder fanboys are still an obnoxious bunch, but the work speaks for itself.

12. The Matrix Resurrections (United States, Dir. Lana Wachowski) is far from perfect, and I wouldn’t have it any other way, because few film artists spoil us with such cornucopias of ideas, insights, feelings, and visuals as the Wachowskis do when they come up to bat. What Lana Wachowski has achieved here, flying solo, is the most finger-on-the-pulse American blockbuster of the 2020s so far, a meta-narrative about what it means to return to old ideas, and a devilishly sharp, pointed barb aimed directly at our brain-dead culture of reboots and IP-driven ‘franchise management.’ It’s an energetic, playful dirge to life in a world that feels like it’s on repeat, where every real idea or moment of inspiration is quickly commodified, defanged, and sold back to us without the soul that first sparked love, all of us moving in circles through a world and media landscape that keeps getting bigger, but feels smaller and more confining every day. And it’s all wrapped together in a soaring romance that, by the end, makes a better world feel so spectacularly possible. Listen to our Weekly Stuff Podcast review here.

11. Mobile Suit Gundam: Hathaway’s Flash (Japan, Dir. Shūkō Murase) is only the first third of a planned trilogy, and it is essentially a 90-minute prelude, with a protagonist who isn’t so much taking action as he is thinking about and preparing to do so. It shouldn’t work so well, at least not on its own terms – and yet it does, a spectacular, smart, soulful production that gets better with each subsequent viewing, and provides one of the most impactful aesthetic experiences the world of Gundam has given us in its 42 years. One image in particular stands out as one of the finest from this or any other year. Listen to our Weekly Suit Gundam review here.

Probably the best image of the year, in animation or live-action

Part III:

The Top 10 Films of 2021

10. Licorice Pizza

(United States, Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

Cooper Hoffman & Alana Haim in Licorice Pizza

Gary and Alana are running. Towards each other, away from each other, nowhere in particular. It is the most memorable recurring visual motif in a film full of them (including long graceful tracking shots and images shot through glass or reflected in mirrors – putting us in the moment and showcasing fractal, hazy identity, respectively), and a synecdoche for what Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest is all about. Two characters, one 15, one 25, running full tilt towards maturity and away from youth, in different directions at different times, attracted to each other because their shared center of gravity is somewhere in the middle.

There’s been a lot of Twitter chatter (mostly, though not entirely, from people who haven’t seen the movie) about the age-inappropriate relationship between the lead characters, and it’s almost all talking past what Anderson is actually doing here. That tension is the animating force of the movie, for one, present and clearly established from the opening lines of dialogue, particularly for 25-year-old Alana, who knows she shouldn’t be hanging around a 15-year-old, but also can’t seem to find any comfort or solid ground anywhere or with anyone else. Movies are, of course, allowed to depict things outside the bounds of acceptable or ‘good’ reality, especially in service of deeper emotional truths. And there’s an awful lot that rings true about how Gary and Alana orbit each other throughout Licorice Pizza. I saw a lot of myself in both of these characters. Gary’s precocious need to fast forward to adulthood and skip everything around him, even as he lacks the actual maturity or empathy to successfully navigate these spaces. The mid-twenties discomfort Alana has in her own skin, unsure of whether to embrace ‘growing up’ or try holding on to youth, and not feeling truly at home in either world. There is agony and ecstasy to it all in equal measure, and it resonates deeply.

That’s due in no small part to the positively stupendous performances Anderson gives his two debut leads space to discover. Cooper Hoffman, son of Philip Seymour, has his dad’s smile, and a similar glint of playful depth in his eyes; Anderson employs both just as surgically as he did with the elder Hoffman, and otherwise encourages Cooper to blaze his own trail. A precocious go-getter who never stops moving, never stops talking, speaks bullshit as often as he does truth, and yet seems entirely genuine in every moment we look at him – this character could so easily rub me the wrong way. Instead I loved him. Alana Haim is a 100% born movie star, a magnetic force of humor and pathos, her work at turns bracingly funny and profoundly heartbreaking, sometimes in the same scene. What she and Hoffman do here barely feels like acting, it’s so raw and expressive and persistently grounded in the moment. I walked out of the film desperately excited for the decades of cinema we’ll hopefully get to enjoy from them both.

Licorice Pizza is a South California memory piece, full of nostalgic signifiers and references to local history and legends. When Quentin Tarantino did something similar in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, it mostly annoyed me. But Anderson is less obsessed with making sure you understand every piece of insider knowledge and trivia, and where Tarantino’s film is rooted firmly in the sensibilities and perspectives of the present – his is a movie told in the past tense – Anderson is vastly more invested in making his film’s pulse beat to the rhythms of its own moment. For all the nostalgia, it’s still intensely present-tense, established from the opening moments as Gary follows Alana around, in Anderson’s signature long tracking shots, which he deploys here more skillfully than ever before. We’re in the moment, with them, and we are from the first time the title appears to the last.

That’s what makes the whole film tic. It’s a series of moments we live in and inhabit alongside the characters. Licorice Pizza is an undeniably (and intentionally) shaggy and loose film, wandering and meandering through episodes that are occasionally riveting, sometimes frustrating to one’s attention, its structure elliptical, always moving but rarely in a straight line. But then again, so is growing up. And there’s a real, vulnerable magic to what the film captures, precisely through its finely crafted shagginess, about maturing on an uncertain timetable.

That’s how it goes with this film. I wasn’t entirely sold on it in the moment, or at least not in every moment. Each time I think about a “problem” I had, I push a little harder and see a bit of wisdom or insight or inspiration that pushes back.

(Well, almost entirely. There’s a joke involving a white man doing a racist Japanese impression that the film, on the one hand, clearly knows is racist – it’s in the mouth of a putz businessman even the kids know is an idiot – but on the other hand fails to contextualize beyond whiteness. A Japanese-American character is there, in both scenes, but denied agency or interiority. It’s a joke built on performative racism, but Anderson has a blind spot about who that racism is being performed by (a white guy), and who it’s being performed for (white characters and a presumed white audience), and there’s an obvious gap in who’s being left out.)

I’m not completely settled on Licorice Pizza yet, though I think that, like a lot of Anderson’s movies, it will probably grow on me and with me in interesting ways. I can tell it’s a film that will continue to live inside my mind. Those performances are just so good. Anderson and Michael Bauman’s cinematography is just so evocative and sensual, every color, every camera movement piercing me in one way or another. The soundtrack, with snippets of original music by Johnny Greenwood (making his first of three appearances on this year’s list), but primarily built on a mixtape of tunes from the time, is pure bliss. There’s a scene scored to the Wings song “Let Me Roll It,” and it’s the best use of Paul McCartney’s post-Beatles catalogue I’ve ever heard in a movie. I once had an idea for a scene in a film I imagined years ago that used that song; I saw the images so vividly when listening to it. Anderson clearly felt the same way. This movie just pulses with so much musicality. Now that Spielberg’s finally taken the plunge and made his musical, Anderson’s clearly the American auteur who needs to try next. You can just tell it’s in his blood.

But now I’m rambling, a bit like the movie itself. I spent a good chunk of the film trying to run away from loving it; but like Alana at the end, I find myself running back. Warts and all, I just can’t deny what it makes me feel.

Licorice Pizza is now playing in select theaters.

9. Spencer

(United Kingdom/United States, Dir. Pablo Larraín)

Kristen Stewart in Spencer

Pablo Larraín’s not-really-a-biopic of Princess Diana announces itself as “a fable from a true tragedy,” and thus describes itself better than I ever could. Larraín takes the raw material of Princess Diana’s torturous real-life relationship to the British royal family, turns it into the story of an imagined weekend illustrating Diana on the cusp of finally cutting all ties to this life, and in so doing crafts one of the great cinematic depictions of depression, anxiety, and abuse, with Kristen Stewart delivering an absolutely towering performance only she could give. Her virtually unparalleled ability among contemporary film performers to wear emotional discomfort through twitchy physicality makes this a fable we feel more than one we watch. The attention her work gives to the way anxiety unconsciously manifests in bodily tics – like hands moving in strange rhythms, fingers clawing at each other because the body has to fight something, somehow – isn’t just powerful, but profoundly resonant to anyone who’s ever found their own body rebelling against itself this same way. It was clearly true before Spencer, and it’s even more obvious afterward: Stewart is simply one of the best actors alive today.

While the entire extended ensemble is very good – particularly Sean Harris as the head chef who seems to know exactly how hard Diana is hurting, and finds himself with few options to help her other than making very fine meals she almost certainly won’t eat – Stewart’s real co-lead is composer Johnny Greenwood, delivering the second-best score of 2021 and appearing for the second of three times on this list. The music is absolutely a character, feeling like the sounds you would get if you somehow laid Stewart’s performance out on a soundtrack – jazzy, discordant, beautiful, prickly, haunting, indescribable. It reminds me of Miles Davis’ legendary score for Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows, not because they’re all that sonically similar, but because it’s the closest analogue I can reach to for a score that feels like it’s somehow emanating from the mise-en-scene, like a ghost escaping from the walls.

The film also has some of the year’s greatest cinematography, shot in rich, grainy 16mm that gives a sort of shimmery, dreamlike haze to everything, framed at the wonderful 1.66:1 ‘European widescreen’ aspect ratio to continually conjure stunning compositions that convey interiority and atmosphere with aplomb. Yes, I’m a nut about aspect ratios – but it’s not incidental (and never is, at least when a movie is shot well). 1.66:1 is such a great shape, like standard ‘flat’ widescreen with a bit of height, or the classical Academy Ratio with a little extra width, and that particular shape is so key to how the movie draws you in and keeps you there, the exacting geometry of every leading line and cavernous height of every room feeling like it’s slowly swallowing you whole. For all the talk about ‘streaming vs theatrical’ in the mainstream space this year, the truth is it’s desperately rare to see a Hollywood wide release nearly as concerned with how to use the shape and size of an honest-to-god Movie Theater screen for maximum effectiveness as Spencer. I look forward to revisiting this film at home, but I think it might lose something when not projected many feet high in total darkness.

One of the great mysteries of movies has always been how they are able to powerfully convey and confer subjectivity, despite mostly showing us the outsides of things. Through such inspired use of all the cinematic tools at its disposal, Spencer is a magnificent case study in this. We look at Diana, yet we also occupy her head. It is magic. Dark, disturbing, enrapturing magic.

Spencer is now available for digital rental on various video platforms, and will be released on Blu-ray on January 11th.

8. West Side Story

(United States, Dir. Steven Spielberg)

Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story is two and a half hours of pure virtuosity, a cinematic masterclass from first shot to last. Spielberg’s never been one to half-ass even his worst films, but there’s a sheer hunger to this one that we haven’t seen from his work in a long time (since The Adventures of Tintin, I’d argue), and he devours this project with the kind of sheer formal skill that can only be honed by age and experience. There is a degree of confidence combined with a raw, undeniable mastery at work here that would be astonishing for any time period of cinematic history, but even moreso today, when the majority of what makes it to the multiplex is lacking in those exact qualities – doubly so when we’re talking about musicals, a genre so touch-and-go throughout the 21st century that it sometimes feels like a dead, forgotten language filmmakers are trying to piece back together from fragments. Spielberg speaks it with absolute fluency. That he, of all directors, could helm one of the greatest Broadway adaptations of all time should come as no surprise – Raiders of the Lost Ark is as well-choreographed as the very best movie musical – and yet the experience is still nothing short of humbling to watch unfold.

Compare this film to In the Heights – another uncommonly great modern movie musical, which I ranked at #17 – and you see how Spielberg is just operating at a higher level. I didn’t dislike the relatively rapid editing in In the Heights as much as some did – it’s at least rhythmic and motivated in the way, say, a bad Rob Marshall musical never is – but it’s clear Jon Chu shot the dancing there with lots of coverage to find the overall rhythms later in the edit. Not so in West Side Story. You can just feel the intentionality behind every shot choice, camera move, and cut here, to the level where this is one of those movies I want to break down shot by shot to study how precisely and fluidly it’s all organized. It feels like Spielberg and company found a novel and interesting way into every single image and sequence in the film; there is a story being told within each shot, a narrative, emotional, and thematic logic to every choice made, a real feeling of a master at work. It is, frankly, startling to see something this immaculately made at an American multiplex released by a major studio in 2021 – it’s not a coincidence this is the year’s highest-ranked wide release on my list.

This is the best visual work Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski have done together in their 30-year partnership. The use of the ‘scope’ widescreen frame is unlike almost anything you see today, every inch employed, the whole frame rich in detail and truly larger than life, but never cluttered or unclear. I am in love with what Kaminski does with light, color, and particularly shadows here – and never just to get a flashy or attention-grabbing image. It’s always to tell the story, to underline character dynamics, drive parallels, illustrate conflict. There is such casual magic at work in frame after frame of this movie. I am in awe of it.

David Newman’s arrangements of Leonard Bernstein’s legendary compositions are breathtaking to behold, especially as performed by the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics, with a truly stupendous, enveloping sound mix to deliver it all. This is the most lushly realized film music I’ve heard in years. And while I’m not crazy about everyone’s singing voice, Jerome Robbins’ iconic dance choreography has always been the centerpiece of this musical, and they absolutely blow the doors off in that department. This is a film awash with movement, and it never settles for just establishing a proscenium and observing theatrically – it captures this movement in an intensely cinematic, immersive 360-degree space.

The lone black mark against Spielberg’s West Side Story is Ansel Elgort as Tony, a subpar actor inexplicably cast in one of the most crucial parts. His voice and physical presence are a notable step below everyone around him, and while I think the script makes smart decisions in fleshing out the character’s backstory and motivations, Elgort translates this too frequently as one-note dourness. He’s not terrible – this is the best work he’s yet done on film – but he’s an unfortunate void of energy and charisma where there should be real passion. And that’s before you factor in the horrific allegations of sexual assault levied against the actor after the film finished shooting, adding an extra layer of unintentional discomfort to the proceedings.

Yet it speaks to what a tremendous production this West Side Story is that the male lead can be such a dud, and so many sparks still fly. Much of that praise must go to the other members of the cast, with at least four names in particular – Rachel Zegler as Maria, Ariana DeBose as Anita, David Alvarez as Bernardo, and Mike Faist as Riff – standing out as such aggressively astonishing star-making performances that one suspects we’ll look back on this film in 20 or 30 years as an absolute Big Bang of cinematic talent (and the one established legend among the cast, Rita Moreno, delivers a true tour-de-force in the reworked role of ‘Doc’).

I was never one of those people opposed to the idea of remaking West Side Story – Robert Wise’s 1961 film is one of the all-time movie musical greats, but the last 60 years have left plenty of space to update this text – yet I am still in awe of how vital and of-the-moment Spielberg’s film feels. Not just in the massively higher degree of authenticity Spielberg invests in here – having the Puerto Rican characters talk in a very natural mix of English and unsubtitled Spanish does wonders – but in how Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner have brought the themes of gentrification and racial hierarchies obscuring class unity to the surface. The outstanding production design places this telling within the bombed-out ruins of late-stage capitalism, making it painfully clear how these characters have so much more in common than what divides them, and yet they have all been abandoned to lead lives of conflict – with each other, with the cops, with the system. The fight and its scars are everywhere. Dance and movement have to become the primary modes of communication, because over and over again, words just aren’t enough. At once a throwback to a different era of movies and of musicals, and a vitally immediate statement of what this medium can still achieve on a broad, populist canvas, West Side Story makes cinema feel truly alive.

West Side Story is now playing in theaters.

7. The Power of the Dog

(New Zealand, Dir. Jane Campion)

It’s hardly surprising that Jane Campion’s first film in over a decade would be a truly great one, but that doesn’t make the experience any less revelatory. This is one of the most delicately and exquisitely crafted character pieces I’ve ever seen, and everything I said about Spielberg’s overwhelming mastery of visual storytelling in West Side Story can be repeated here for Campion, whose eye for illustrating character detail through cinematic language makes The Power of the Dog several semesters of film school in a box. It’s one of those films where, no matter how many movies you’ve seen or how much you think you know, you will find yourself learning new dimensions of cinematic technique and craft from how Campion stages a scene, or chooses a shot, or builds space for an actor. It is a truly towering work, in part because it is so quiet, so delicate, so supremely confident that it never feels the need to announce its brilliance or intentions. It just soars, and you may not realize how far it’s burrowed under your skin until it’s already gone too deep.

This is truly one of the great films about masculinity – specifically, the way masculine expectations, ideals, and myths affect a man’s relationship with his body and his surroundings, and how that can curdle into the deepest poison when a discomfort or disconnect arises. As the cruel, obsessively masculine rancher Phil Burbank, Benedict Cumberbatch easily gives the best performance of his career, an avowed and archetypally perfect ‘man’s man’ cowboy whose precisely crafted body is both a shield from the world and a prison from which he can’t feel his way out. He lashes out and pierces everyone around him, and the more he lacerates, the more we see how many secrets he harbors from both the world and himself, and the increasingly complicated layers of humanity simmering underneath.

Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons, and Kodi Smit-McPhee all move through the film alongside him, waxing and waning in significance based on their proximity to Phil, everyone quietly shining, but Smit-McPhee holding the film’s deepest intentions closest to his chest. Yet the greatest co-star might, as with Spencer, be composer Johnny Greenwood, with his third score of the year and third appearance on this list – truly a banner creative year. All his 2021 scores are quite different from each other, with The Power of the Dog reminding me more of his work on There Will Be Blood, his strings dancing atop and participating in each scene, an active force in the action, like a musical embodiment of the pathology plaguing this setting. Ari Wegner’s extraordinary cinematography lenses New Zealand in place of the American West, and it feels appropriately mythic – not quite New Zealand, not quite America, but a world conjured out of Western books and paintings, with landscape shots that directly evoke the latter. At every level, the visual work here is astonishing, and while I’m glad the Netflix release gives viewers around the world an easy, safe way to access Campion’s work, this is an essential big-screen experience if there ever was one. The film is dense and smart and dripping at every corner with empathy and insight – a movie of profound wisdom and humanity, even as what it presents is consistently painful and difficult.

The Power of the Dog is now streaming on Netflix.

6. The French Dispatch

of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun

(United States, Dir. Wes Anderson)

Bill Murray and Owen Wilson in The French Dispatch

Just when you think you’ve seen everything in Wes Anderson’s bag of tricks, he manages to make you fall in love all over again. After many years of adoring Anderson’s work, 2018’s Isle of Dogs was the first that fell flat for me – surprisingly, considering it combined stop-motion animation, Japanese cinema homages, and most importantly, dogs – while this year’s extraordinary, playful, profoundly human triptych The French Dispatch made me feel like I was discovering my love for this director anew. I think it’s his funniest film to date, equal parts dry and side-splitting, but also one of his warmest and most soulful, a marvelous little Russian nesting doll with a million things on its mind: How stories are told and culture is constructed; the simultaneous folly and wisdom of youth; the joy of storytellers and their idiosyncrasies. All wrapped in a package that is so light on its feet, so self-aware, so full of heart and wit and exquisite, eclectic craft. It is such a lovely gift of a movie.

Styled as the final issue of a venerable New Yorker-style magazine, The French Dispatch takes us through a travelogue, three short stories, and an obituary, all simultaneously playful and wistful. This is one of two films on my list this year that’s a cinematic short story collection, and between these and the Coen Brothers’ 2018 film The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, I must say I love the revival of the form. Not every story in Anderson’s triptych works equally for me – the first, involving Benicio del Toro as a crazed inmate artist and Lea Seydoux as his guard/muse, is my favorite, a delicious send-up to the world of high art that is never anything less than loving, although the third story has my favorite beat of the whole film – but the cumulative effect is more than the sum of its parts.

Purely on the level of linguistic construction, this is probably my favorite script Anderson has yet written; the words have such a poetry and musicality to them, playfully tap-dancing upon the lips of this incredible ensemble, until those moments when they unexpectedly knock you flat. That aforementioned beat in the third story involves one such moment, a quiet exchange between Jeffrey Wright and Stephen Park – as writer Roebuck Wright and police chef Lt. Nescaffier (God, I am in love with the names in this movie) – and it is not just a stunningly beautiful exchange of words laced with wisdom, but one of the most teachably perfect moments of denouement I’ve ever seen in a film. Knowingly so, of course – Anderson frames it as such – but that’s also the point of the movie: How we search for stories, and the meaning they provide in defanging mysteries through narrative structure, because we are all wanderers in this life.

I have little doubt The French Dispatch will play like nails on a chalkboard to the small but vocal contingent for whom Wes Anderson is nothing more than an obsessive, finnicky stylist, but permit me a moment to sing the praises of that style. Because Anderson is someone for whom style has always equaled substance – the best directors often are – and the more he hones, refines, and sharpens that style – the more he sheds the pieces that are no longer quite his own, and embraces those that very much are – the more I feel there is to enjoy and think about and be moved by. He reminds me of Yasujiro Ozu or Robert Bresson in that way, an artist who adds by subtracting until all that’s left is uniquely and ineffably his own. The French Dispatch may be his most aesthetically rich and singular creation. The Academy Ratio – that classical, more square and tall shape of old TVs and movies – has been making quite the comeback over the past decade, a trend I am very much pleased by, but none understand how to employ it quite as instinctually as Anderson. He fills the frame top to bottom and side to side with carefully composed geometric detail, the height of the frame in particular used to full effect. The whole idea of this shape, in its conception, was to be staring up at it, the image towering over you, awash in detail. Anderson and cinematographer Robert Yeoman embrace the possibilities even more than they did on The Grand Budapest Hotel, their first film made in this style. Watching The French Dispatch makes me feel like I’m in an old movie palace, dwarfed by the image, spoiled by frames of such rich color and composition. It’s one of the year’s most essential big-screen experience, inevitably less powerful on a TV, where one cannot get the same sense of breathtaking scale – things that would look “small” on a television are so big here, yet only take up a fraction of that bigger frame. The movie understands the power of its canvas on a chemical level.

Anderson has, at this point, found a large stable of regular collaborators who clearly share a wavelength, from composer Alexandre Desplat – always at his best and freest when composing for Anderson – to the massive ensemble cast, many of them repeat players, who each fit inside this world like it’s a glove made just for them. Wes Anderson isn’t a director likely to surprise us with a sharp stylistic turn against his own grain, but that doesn’t mean his work is out of new pleasures to discover. The French Dispatch is at once his most indulgently auteurist work, and one of his most consistently surprising and moving. Artists are like that, sometimes; the closer they come to finding the center of themselves, the more they have to offer the world.

The French Dispatch is now available on DVD and Blu-ray and for digital rental on various platforms.

5. Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train

(Japan, Dir. Haruo Sotozaki)

Kyojuro Rengoku, preparing to conquer the hearts of 1000 fans

After a year and a month without stepping foot in a movie theater, the American debut of the Kimetsu no Yaiba movie this April – months after it set all-time box-office records upon release in Japan – was my first time back seeing a film on the big screen. To say it was overwhelming would be an understatement – both the shockingly emotional feeling of stepping foot in a multiplex again after so long away, and the movie itself, which was so ludicrously good that when the credits finished, I walked outside, bought another ticket, walked back in, and watched it all over start to finish. Koyoharu Gotouge’s original manga is one of the best Shonen mangas ever created, taking all the well-trod themes and archetypes of the genre and thoughtfully concentrating and reconstituting them until they feel fresher and more powerful than ever before, and the first season of Ufotable’s anime adaptation, aired in 2019, is about as accomplished an example of the form as you’re likely to find, nothing less than groundbreaking in its visual style and consistently making smart, thoughtful choices as a piece of adaptation.

It feels perfectly natural, then, that this film – a direct follow-up to the first season, adapting a short 16-chapter arc from the manga – would be historically great. And yet, what Ufotable have accomplished here still manages to surpass all expectations. Mugen Train is nothing less than the best, most structurally solid, emotionally resonant mainstream pop action masterpiece since George Miller’s Mad Max Fury Road in 2015, and belongs on the shelf alongside not only that film, but similarly transcendent works of cinematic entertainment like Raiders of the Lost Ark and The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Like those films, Mugen Train displays such a masterful command of cinematic three-act structure that it deploys it like a weapon, the shape and pace of its story so surgically effective that even after 5 viewings in under a year, its impact on me has only increased. A technical marvel animated with such wild amounts of imagination and skill that it frequently takes one’s breath away, and featuring the very best musical score I heard in a film all year (a year that came with quite a bit of stiff competition on that front), the real heart of Mugen Train lies in how cleverly and passionately it approaches the source material. It’s less a translation of the manga than it is a critical reaction to it, simultaneously expanding upon the scope and ideas of Gotouge’s original chapters while focusing in with even greater clarity than the author did on the ideas and themes at the heart of the material.

This is one of the great films about a ‘pyrrhic victory,’ the win that feels more like a loss, because of how beautifully the film illustrates the ways our humanity is predicated on transience. Featuring great moments from the entire Season 1 cast – and a particularly powerful vocal performance from lead Natsuki Hanae, whose work as Tanjiro in the closing minutes should send a shiver down the spine of anyone with a pulse – and making an all-time great anime icon of Kyojuro Rengoku, who so easily have been a relatively minor character in the grand sweep of this story, it’s hard to imagine anyone invested in Kimetsu no Yaiba walking away from Mugen Train anything less than ecstatic. But I think this is a movie for more than just the already initiated. It will play most powerfully to those who have seen the preceding 26 anime episodes, but it stands resolutely on its own as a great piece of cinematic art, and I have to believe even viewers who go in cold would be astonished by what they see here. In a world where ‘interconnected storytelling’ is quickly becoming the multiplex’s primary form of expression, Mugen Train puts any fantasy spectacle Hollywood had to offer this year to absolute shame.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train is now available on Blu-ray from Funimation, and streaming on Funimation Premium and Crunchyroll Premium. Listen to our full Weekly Stuff Podcast review and discussion of this film here.

4. Days

(Taiwan, Dir. Tsai Ming-liang)

Lee Kang-sheng and Anong Houngheuangsy in Days

Sometimes, movies fall into your lap exactly when you need them most. Back in August, I spent weeks trying to figure out when and where I could see Tsai Ming-liang’s latest, even pricing out a day trip to Chicago to see it there. This coincided with an increasingly difficult couple of weeks in my personal and family life, and I remember feeling like there was something in Days that I needed to see, something that would help me cope or heal. And then one day, in early September, there it was: American distributor Grasshopper Films had dropped the film on their digital rental platform, and I was able to watch it that night. It was, indeed, a movie I very much needed.

I think this would be true for a lot of people, even those previously unfamiliar with Tsai’s work. There is perhaps no director alive today better equipped to capture on film the feelings of isolation we all collectively confronted these past two years. Tsai is one of the foremost masters of ‘slow cinema’ – durational works where individual shots last many minutes, little in the way of concrete ‘action’ occurs, and you sometimes find your patience tested right up until the moment this slowness leads to revelation – but he is also one of the medium’s great conductors of loneliness. In his decades-long collaboration with actor Lee Kang-sheng, who has appeared in all Tsai’s feature films and many of his shorts, Tsai follows characters detached from the world, from others, from themselves. His works are always built around characters and emotions most filmmakers would ignore or elide, and there is a beautiful, haunting poetry to how he cinematically illustrates feelings of isolation and detachment. His films are often quite sad, but in their sadness, they are also ecstatic, because they are so profoundly human.

Days pushes Tsai’s style into extremis. It is the simplest of his feature works, featuring only two actors and characters: Lee Kang-sheng, as always, playing a version of the character he and Tsai have been developing for thirty years, here named Kang; and Anong Houngheuangsy, a non-actor Tsai discovered by happenstance, playing Non, his first film role. Kang lives alone in a secluded, sprawling house, but descends from the mountains into the city to seek treatment for shoulder and neck pain. Non is, basically, who Houngheuangsy is in real life, as Tsai found him: a Laotian immigrant to Thailand doing odd jobs. In long, still sequence shots, we watch Kang undergo acupuncture treatment and Non wash vegetables in his apartment as he prepares to make dinner. It’s not quite documentary, and it’s not quite fiction (most of the scenes in the film’s first half were captured by Tsai without a clear plan on how or where he’d eventually utilize them). Eventually, their two orbits coincide: Kang schedules a massage, and Non is the one who gives it. The film’s centerpiece is this 20-minute scene, which starts as a full body massage and ends in sex. All of it is deeply sensual, a long unbroken series of images of one man’s hands on another’s body, and eventually both bodies in fuller physical contact. Yet the magic of Tsai’s filmmaking is that the scene that follows – both men clothed, the camera much further back, with minimal if any bodily contact – is somehow infinitely more intimate, raw, and vulnerable. Kang gifts Non a little music box, which plays the melody of Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight. They share a few words, which we aren’t privy to hear. They don’t see each other again. It made me cry.

Days is a masterpiece. Tsai’s command of ‘slow cinema’ is here refined to an impossibly hypnotic, engrossing degree. Time slips away, and we come to live in the moment, inhabiting the images, sitting with the feelings. The cuts from one shot to the next, usually the most ‘invisible’ part of film, become agents of affect. So infrequent, so unbound from rhythm, they shock us, feeling like actual ‘cuts’ to our bodies. The most basic linguistic unit of cinema astonishes anew. And yet, as quiet and as glacial as the film’s movement is, the entire thing is constructed with the intricacy of a fine watch to absolutely demolish the viewer emotionally. Not because Tsai wants to hurt you, but because he wishes to extend the artistic generosity of building a meditative space within which you can think and feel in peace. He guides you, gently, but the images are truly an open canvas on which to project and reflect. No two viewers will see quite the same film, and no one viewer will have quite the same experience if they see this one twice. Tsai has increasingly worked in museum installation spaces over the past decade, and that’s certainly a fitting way to consider his work, but I’d also liken them to a temple. There is something deeply spiritual about Days, like we are connecting with something higher as we take it in, even if that higher presence is just another level of our own heart we realize we’d been ignoring.

I find it difficult to describe this film. That’s ok – a work this rooted in the intangibles of image and time can only be done so much justice in words. I implore you to watch it. Maybe save it for a hard day, and give it a chance; allow yourself to be taken aback by its style, and enraptured by Lee Kang-sheng’s unmoving yet infinitely expressive face. See what images unexpectedly fascinate you, like Houngheuangsy methodically washing lettuce, and look for those moments when the effort of duration slips into a sort of timeless trance. Maybe you, like me, will learn you needed it all more than you could ever express.

Days is now available to rent digitally or pre-order on DVD and Blu-ray from Grasshopper Films.

3. Evangelion 3.0 + 1.0:

Thrice Upon a Time

(Japan, Dir. Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki,

Katsuichi Nakayama, and Mahiro Maeda)

Shinji Ikari contemplates life, the universe, and animation

If I could pick one sentence to describe how most of 2021 felt, it would be this:

“The world is ending.”

Not literally, I guess. The planet’s still spinning. I’m still alive, as are (most of) my loved ones. I still go to work, teach classes, write papers, record podcasts, watch movies, play games, talk to friends. Life goes on. But it all feels so contingent and fragile. The pandemic ravaged our global population and upended social and lifestyle norms for a second straight year, and while we in the US had the benefit of a new President who was, at the very least, not actively psychopathic in his approach to the virus, we’re still fighting this thing on our own more than we should have to – as we also experience ever more frequent climate disasters, navigate an increasingly brittle democracy poised in every way to implode, and grapple with the perennial problems of health care, debt, stagnant wages, and dwindling economic prospects. With every day that passes, it feels more and more obvious that my generation and those younger than me have been abandoned, saddled with broken political systems, untenable debt, threadbare or nonexistent social safety nets, and having to choose every day to focus on the crisis of the pandemic that is right in front of us, or stare down the barrel of the oncoming tides of authoritarianism and apocalypse.

So yeah. The world hasn’t ended yet. But it sure feels like we’re on our way there.

Few films of the 21st century have captured this sensation – of being a young person living amidst an apocalypse you never signed up for – as eloquently and bombastically as Hideaki Anno’s Rebuild of Evangelion saga, a 4-film project begun in 2007 to remake Anno’s seminal 1995 TV anime Neon Genesis Evangelion for a new generation. The first 3 films were released in 2007, 2009, and 2012, before Anno found himself at a creative impasse and went off to direct one of the best films of the 2010s – 2016’s thoroughly remarkable Shin Godzilla – which led to a 9-year gap before the final Evangelion. Those first three entries are each terrific in their own right, gracefully and passionately expanding upon the themes and mythos of the TV series before largely breaking off in their own narrative direction. I have my fair share of problems with the original anime, but the first three Rebuild films did the seemingly impossible task of enhancing everything that resonated so powerfully in that show, while excising or reworking everything that didn’t. I love them, in a way I was never able to love the original.

And yet. This year’s final film, the 2.5-hour-plus epic Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time, exists on an even higher caliber of virtuosity and impact. It is a masterpiece, full stop, an absolute landmark of animation, of digital cinema, of world cinema, of popular avant-garde experimentation, of visual art itself – and a profound work of and for our pseudo-apocalyptic times. It looks straight into the broken heart of that despair and malaise that comes with living amidst the end times, allows those feelings full and undiluted expression, and then sets about imagining a future anyway, one illustrated both in simple acts of communal kindness and in purely abstract, expressionistic chaos, the spectacular sound and fury of a world being reshaped by those left behind to live in it.

The sheer lift of this project is mind-bogglingly monumental. It aims to put a bow on not just 3 other films’ worth of storytelling, but to a larger and even more complicated tale that’s played out over 26 anime episodes, a full feature follow-up (1997’s The End of Evangelion), a manga, and perhaps most importantly, 3 decades of impact, influence, dissemination and discussion in the minds of fans and viewers – all of which are bubbling on or just under the surface throughout this final film. This movie is far less accessible to the Evangelion uninitiated than Mugen Train is to those new to Kimetsu no Yaiba – at a minimum, you need to see the first three films of the Rebuild series, though to fully appreciate everything Anno and company are doing here, the original series and End of Evangelion are also prerequisites – but if you’ve been along for the ride, the result is one of the richest transmedial and cross-temporal media texts of the 21st century. It is an Evangelion movie about the history of Evangelion media, an ending about the idea of endings, an anime about the aesthetic substance, fragility, and boundless potential of animation. “Multivalent” doesn’t begin to describe it. Multiple books could be written about this film with only minimal overlap.

It’s also one of the most spectacular animated productions ever mounted. Hollywood routinely spends $200 million or more on CGI-animated films, and I have never seen one that looks a fraction as expensive as this much-lower-budgeted film does. Vision is truly priceless, and this final Evangelion has that in spades. It is a virtuosic symphony of cinematic construction, ambitious and experimental to degrees we simply have no analogue for in American popular cinema. To watch this film is to sit in awe of its extraordinary craft.

Of course, it all only matters if the film satisfies in its first order creative responsibility – to satisfactorily continue and conclude this new journey through Evangelion – and on that level it is an impossibly rousing success. Compare Thrice Upon a Time to End of Evangelion, which is such a fundamentally bitter and nihilistic movie, and it’s clear how open-hearted, humanistic, and full of love this new film is, without sacrificing one ounce of Evangelion’s avant-garde spirit in its push towards hope. This film does both of the two main things I always wanted from an Evangelion ending – watching protagonist Shinji Ikari come fully into his own personhood, and to finally give him a real, meaningful confrontation with his nefarious father Gendo – and it does both more powerfully than I could have imagined, while also doing right by every other character, old and new. There is not a single figure on screen who is not fully, triumphantly human in this final chapter.

The film is, essentially, comprised of two halves: One a relatively down-to-earth story set in one of humanity’s last remaining settlements, a pastoral haven perpetually on the verge of destruction, where Shinji is given the space to work through his latest and greatest bout of depression, and the viewer reflects on the resilience of humanity and the human spirit, which has no choice, even in the darkest of times, but to live. The second is more bombastic, abstract, and metatextual – as it must be, for this is still Evangelion – but the elegy it sings is so empathetic and big-hearted. Through Shinji, Anno finally lets go of Evangelion – a work born in the fires of his own depression, and which has clearly gnawed at him for almost 30 years – and paints a vision of a future without it. A future without the stories we cling to as balms for our trauma and uncertainty, without the icons we invest in while our fragile present breaks apart around us. Shinji finally grows up. Anno does too. And the viewer sees a world beyond the apocalypse – one no one can create for us but ourselves.

Evangelion 3.0 + 1.0: Thrice Upon a Time is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video, along with the first three films in the series. Listen to our full review of this film and the entire Rebuild of Evangelion tetralogy on the podcast here.

2. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

&

1. Drive My Car

(Japan, Dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Fusako Urabe and Aoba Kawai in Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy

At the start of 2021, I wasn’t familiar with Ryusuke Hamaguchi or his films. At the other end of the year, he is firmly one of my very favorite filmmakers, and I’m obviously not alone. While Hamaguchi had certainly made a splash in some circles before, his one-two punch in 2021 of Wheel and Fortune and Fantasy and Drive My Car made him impossible to ignore. The former was comfortably my favorite film of the year since I saw it in early November, right up until I finally had the chance to see Drive My Car a few weeks ago. The combined five hours I spent watching these two films were without question the most valuable I devoted to consuming and digesting art this year, if not quite a bit longer. Both films are – and I mean this in the best way possible – a form of in-depth movie therapy. I came out of each understanding more about myself, my feelings, my relations to others and the world around me; about cinema and the boundless possibilities it still contains within; about language and the sheer power of simple words spoken honestly; and so much else. Both films put me through an emotional wringer and left me in a cathartic daze – teary-eyed, raw, shaken, and above all else grateful for the understanding Hamaguchi and his art led me towards.

The Japanese title of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, “Gūzen to Sōzō,” translates as “Coincidence and Imagination,” and it is the better title for the film, a triptych of short stories all built upon happenstance and random encounters, each exploring a place of gnawing emptiness inside the characters’ hearts, and revealing exquisite humanity along the way. It is a film built almost entirely around conversation, evocative of short stories or one-act plays, but it is intensely cinematic in the same way My Dinner with Andre is – because those formal qualities of cinema that bring us into these conversations (shot choice and composition, editorial rhythms, carefully patterned sound design, the magic of a well-employed close-up) creates the kind of startling and gripping intimacy only a masterfully made film can offer. The movie is by most standards quite slow, each story starting in a simple and quotidian place before carefully, gradually unfolding its many layers, but it is at each stage intoxicatingly absorbing. Time slips away. What these conversations – and all the countless nuances of acting and filmmaking that bring them to life – reveal are remarkable. Each story was, to me, better and more creatively surprising than the last, but each arrives at a place of arresting and lacerating emotional honesty. The third story, in particular, is probably my single favorite stretch of cinema released this year, its closing minutes coming as close to putting into words what it feels like to live on earth in 2021 as I think it may be possible to do.

“I’m not passionate about anything anymore. I don’t know what to do. Time is slowly killing me.”

Hidetoshi Nishijima and Tōko Miura in Drive My Car

Yet in its totality, the three hours of Drive My Car are an even greater accomplishment. Inspired by the Haruki Murakami short story of the same name, Drive My Car finds Hamaguchi stretching his dramatic legs to let a simple story unfold at its most natural pace, wherein we are continually struck with how complex, fraught, layered, nuanced, and meaningful the tale truly is. A middle-aged theater director and actor, Kafuku, suddenly loses his beloved wife Oto (the Japanese word for sound – and it’s not a coincidence; we’ll continue hearing her voice throughout the movie), shortly after learning she was having an affair, and just before they seemed on the verge of talking about it. Two years later, he accepts a residency in Hiroshima to mount a performance of Chekov’s Uncle Vanya in his own characteristic, multilingual style, where the younger actor who may have been sleeping with his late wife auditions for the play. For liability purposes, Kafuku isn’t allowed to drive his own car – a red Saab 900 – and is given a quiet, young driver, Watari, who may be harboring losses similar to his own.

It may not sound on paper like a story to fill 3 hours – Murakami’s short story only runs 30 pages after all – but it’s as full and engrossing a use of cinematic time as you’ll ever find, fueled by outstanding, deeply watchable performances – particularly by leads Hidetoshi Nishijima (Kafuku) and Tōko Miura (Watari), though every actor who appears is absolutely wonderful – and Hamaguchi’s eclectic thematic interests. I would primarily define this as a film about loss, but it’s also a film about the creative process, about acting and directing and the simultaneous joys and dangers of giving oneself over to art. And it’s a film about language, about the beauty of the spoken or signed word, the mysterious wonder of seeing human beings give tangible form to ideas, even (or especially) when we do not understand the words and gestures used.

Words are of such compelling significance here, and as with Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, Hamaguchi’s script (co-written here with Takamasa Oe – and it’s easily the best screenplay of 2021) is so delicately beautiful. I don’t speak enough Japanese to understand it all fluently without subtitles, but I do know enough to at least pick up on the cadence and style of the writing, and it is a wonder to behold. Hamaguchi’s verbiage in both films is simple and unadorned, almost Hemingway-esque, and when it bowls you over, it does so gently. He directs his actors to speak slowly, not unnaturally so, but enough that we can always hear the words being formed, and savor their construction and flavor. Hamaguchi is a masterful visual artist, an imagistic storyteller as deft and skillful as Spielberg or Campion or any of the other great names on this list, but he is also deeply invested in the power of carefully written words spoken well. A large slice of Drive My Car is built around Kafuku grappling with the strange sway Chekov’s words hold over him, how he is both in love with and afraid of a text like Uncle Vanya, because he knows these words will inevitably reveal something about him when he performs. Something he may not yet know, or has chosen to hide from himself. Hamaguchi’s words operate the same way on the audience. You cannot listen to writing this plainly, sparsely brilliant, fluently or in translation, especially when spoken by such gifted performers, and come away unchanged. The words shine a light on us. As these characters put words to such fraught and complicated truths, we start finding the verbiage for our own.

Drive My Car isn’t quite the ‘4th story’ from Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, but the two films do feel like they belong together, reflecting and refracting upon each other in ways that make both films richer than they are on their own (which is, of course, already richer than most movies). If you’ve noticed a theme among these last few eclectic entries on my list, it’s that the films that touched me most this year are the ones that feel most of and for this turbulent, traumatic moment in time. Collectively, Hamaguchi’s 2021 masterworks are the most meaningful reflections of our challenging emotional reality, because the 4 stories across these 2 films are all, in some way and to some degree, about navigating a world that no longer makes sense. A world that has been rocked and broken and torn out from under a person by losses of various forms. Each story revolves around people who are having to rebuild themselves and their relationship to the world in the wake of that loss, and in each case, they find it is something that can only be done through contact with others, through allowing oneself to live inside those feelings in moments of struggle, with vulnerability and empathy and an openness to both let others in and extend a hand to the person across from you.

Of course, that means these are movies for every moment – movies for humanity and the human condition, because what they confront is the basic question of what it means to be alive, and to go on living.

Like a lot of things, we just feel it all more acutely right now.

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is now playing in select theaters, and available via Virtual Cinema from distributor Film Movement. Drive My Car is now playing in select theaters.

Follow Jonathan Lack on Twitter