Meditations of a Celestial Being: Belated Thoughts on Terrence Malick’s "Knight of Cups"

It was less than a year after the release of Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life that we began to learn about the production of the film that would eventually become Knight of Cups. I feel like the film was out there, discussed and speculated upon, for more or less the entire time I was in college, as Malick’s subsequent film, To the Wonder, came and went, and as our knowledge of this project and Malick’s next feature, now titled Weightless, were gradually untangled. Near the end of 2014, in advance of the film’s unveiling at Berlinale, a trailer made its way online. I rewatched it again today, and I contend now, as I did then, that it is one of the more intoxicating, exciting movie trailers I have seen in years. Though I can sometimes feel like a Malick agnostic, my interest in and love for his works ebbing and flowing, this was a film I wanted to make a priority, based on everything we had seen so far.

And then a strange thing happened. The film came and went, from Berlinale to an international release to quietly, a year later in early 2016, an extremely limited theatrical bow in the United States. Few talked about it. Critics mostly scratched their heads or dismissed it. And while Malick’s films have never and will never set the box office on fire, from what I can tell the film grossed less and was seen by a smaller audience than any of the director’s previous features. The film was in theatres so briefly here in Denver that I missed it entirely, to my great regret, and had to wait for the eventual home video release to finally obtain it – and longer still until I found myself in the headspace to sit down and watch it.

What a curious situation. That a director of Malick’s stature, a filmmaker whose early promise and decades-long disappearance made his 21st century films major events in the arthouse and critical communities – think of the sheer size of the discussion surrounding The Thin Red Line, The New World, or The Tree of Life – should have a new film released to such a collective global shrug. And only five years after winning the Palme d’Or, no less. The situation is probably not unprecedented, but it certainly is unexpected.

Continue reading after the jump...

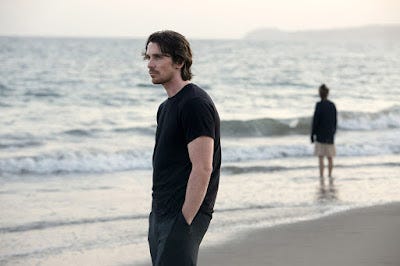

The reasons are not necessarily hard to grasp. Knight of Cups is Malick’s most experimental and enigmatic work by far, eschewing narrative entirely and presenting what seems on the surface like familiar subject matter – the loneliness and existential confusion felt by an actor (Christian Bale) in LA – in more or less the least inviting way possible. I feel like I could comfortably show my family and friends films like Badlands, The New World, or The Tree of Life, and while the films may play differently than the mainstream works they are used to, I am sure they would get something meaningful out of the experience. Knight of Cups, on the other hand, has so few lines of diegetic dialogue – lines spoken by actors on screen and in frame, rather than inner monologue and voiceover – that I’m fairly sure I could count every one of them on both hands and still have a few fingers to spare. The film is ostensibly structured as a series of ‘chapters,’ each one named for a Tarot card and built around a relationship or encounter Bale’s character has, but the pace and structure of the film is at once much looser and far more rigorous than that description suggests. Knight of Cups is not a mainstream film. It may not even be a narrative feature, playing much more like one of Stan Brakhage’s lengthier avant-garde epics (albeit with sound). The number of viewers on Earth who could comfortably sit through the entire film is probably quite small, a fraction even of Malick’s usual audience. Widespread acclaim and attention was never in the cards.

For my part, while I do not necessarily think this is a ‘major’ work of Malick’s, it is not one I can easily dismiss or toss aside, as many (if not most) have already done. When the credits rolled, and I stood up off the couch to walk away from it, I felt chemically altered, the photography by the great Emmanuel Lubezki deeply affecting the way I saw and felt the world around me, the way my body felt in relation to all external stimuli. Particularly in his collaborations with Malick, watching Lubezki’s cinematography is like stepping into another being’s pair of eyes, for a time that is in reality finite but feels as though it exists without beginning or end. The experience is powerful. Infectious even. I got very thirsty watching the film, and wanted to pause it to go get a drink of water many times, but never did. I could not bring myself to. Similarly, I felt myself become self-aware of the experience several times, feeling the urge to laugh at lines and moments that can, in all honesty, come across as self-parody for the director (the number of time Brian Dennehy, playing the father of the Bale character, is made to dramatically whisper “My son…”). But again, I never did. All these familiar instincts fell away, in one way or another, because I was under the film’s spell, inside of the film’s vision, invited along its path of meditation and prayer, and deep down, I did not want to leave until it let me.

How does one review a film like this? How does one judge it? How does one interpret it? Are any of these actions truly necessary? Perhaps that question alone is what makes an experience like Knight of Cups revelatory – and, for some, frustrating, a blow to one’s purpose and ego. It largely eschews the need for verbalization, let alone categorization and qualitative analysis. It exists, like a large and enveloping painting, with no clear beginning and no real end, and the experience of being within its grasp is the thing that actually matters. I find that refreshing. The older I get, and the more films I see, the more I value that kind of experience. I do not know if Knight of Cups is ‘great,’ and that is not what I am here to tell you. But I do know that it is special, and in its own weird, wonderful way, it is valuable.

I mentioned before the sensation of entering another pair of eyes. It is one I am always intensely aware of in Malick and Lubezki’s collaborations. To Malick fans, it was no wonder that Lubezki was able to pull off the awe-inspiring one-shot trickery of Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Birdman, for while he has always been able to capture the colors and contours and textures of the world with a uniquely sensitive eye, it is in his works with Malick that Lubezki has revealed his full talent for moving the camera in ways that are powerfully sensual and experiential, small motions of the frame itself speaking as loudly as the images captured therein. It is an aesthetic voice that, while rooted in Malick’s earlier features, was truly introduced in The New World – Malick and Lubezki’s first collaboration – honed in The Tree of Life, and now permutated upon in To the Wonder and Knight of Cups. At this point, it has developed into an utterly unique way of capturing the world. Malick and Lubezki’s images are of and are in constant movement, with balletic editing and framing that looks at nothing in particular and everything to the horizon, perfectly content to miss an actor’s face in favor of something less concrete and distinct. It is clearly a point-of-view that is being fashioned, captured by Lubezki behind the lens and assembled by Malick at the editing station. But whose point-of-view is it exactly? These images are arranged, in tandem with the dense and beguiling sound mix, as fragments of memory or thought. But of whose memories and thoughts?

These questions become more relevant with each film Malick makes, and I found it of particular interest in Knight of Cups. Is it a meditation, perhaps? The film exists as a state of internal narrative where thought, memory, insight, and seemingly random bits of nothingness pass through, in circles of clarity and non-clarity, distinction and void, focus and wandering. Is it the meditation of Christian Bale’s character, a series of feelings and memories worked through long after the fact? Perhaps, but I tend to favor other interpretations, for Bale is mostly playing an arbiter here, and while his character is our earthly anchor to these images, the common factor that ties all these stray sounds and experiences together, I am not sure if it is even really his story. It strikes me as the meditation of a celestial being, a God or an angel or a spirit passing through our world, roughly focused on the Bale figure but interested more in some enigmatic, ungraspable component of the human condition.

Viewing the film as the internal monologue of a celestial being also helps to explain the sense of exhaustion that settles in while watching the film, the sense of aesthetic overload that quickly becomes overwhelming, and makes the film feel far longer than its relatively svelte two-hour runtime (I do not say this as a criticism, though the pace will undoubtedly be the source of defeat for many a viewer). Each of the film’s many overlapping sequences plays like a little film in and of itself, barreling through snippets of larger scenes and events, the audio consisting of snatches of dialogue from bigger conversations, with narration and monologue and sounds from who-knows-where cascading on top. The film is very musical in that way, like movements in a symphony – albeit aesthetically dense in a way only an audiovisual medium like this can be. It is exhausting in just how much there is to process at any given moment, in the sheer amount each scene suggests of a larger world and of the lives of the many characters contained therein. Malick races through these moments without much care for the particulars, and with instead a rough, emerging patchwork view of the whole that moves in seemingly aimless circles.

It is my instinct to argue that this celestial meditation finds form the further along it goes, that thematic conclusions and meaningful revelations come into focus the more time one spends with the film. Yet I fear that were I to make that argument, the mere act of doing so might defeat my initial thesis, for if I try to explain in words what I got out of the film’s final stretch – from when Natalie Portman shows up through the end credits – I doubt I would be able to say anything of great meaning. The simplest observations – that this is a film about detachment, depression, aimlessness, and excess in all its forms – absolutely come into sharper focus the more one watches. But when the time comes, do I have deeper things to say about those ideas?

Certainly, those final movements of the film produced in me the kind of reverie Malick’s works are known to create in the hearts of his viewers. Perhaps this is, in part, because the director moves closer to his home field the further Knight of Cups moves towards its end. Malick is a director who observes nature, whose stories and characters exist within larger natural frameworks where people are no more important than a ray of sunshine or a blade of grass. Here, however, Malick trains his camera on manmade structures, on the cityscapes and transit planes in which we spend most of our earthly time, and which is, in and of itself, unnatural (and in writing that, I may have stumbled across the thesis of the film, for Knight of Cups is at its core a movie about observing the manmade world and the many anxieties an absence of nature produces). Buildings, elevators, skyscrapers, apartments, human structures of all kinds – Malick has flirted with them before (as in the Sean Penn scenes in The Tree of Life), but never immersed himself inside them as he does here. It is, for students of his work, off-putting. If the film leaves one cold, I think part of that is intentional; Malick has set his action within a framework he finds to be inherently suffocating. To me, trying to apply and extend the director’s now-typical approach to human drama within these manmade structures makes for a compelling and thought-provoking experiment.

But to return to my larger point, when Natalie Portman enters the picture, and Bale’s character seems to find a higher plane of meaning and happiness within her arms (however fleeting it may be), the action moves outside of Los Angeles – to the coast, to the sea, to the desert, to the plains, to the kinds of places in which Malick typically finds profundity. And indeed, some of the photography here is breathtaking. It is no coincidence that as Lubezki’s seascapes make us gasp in awe, Bale is finally allowed to smile. To Malick, natural wonder and personal fulfillment go hand in hand.

Equally powerful are some of Malick’s cuts. In one scene, Bale and Portman wander through an American-made Japanese garden, where the caretaker extols the virtues of monastic life, and suggests living within the moment, for it has all one needs to understand and be happy. And as he speaks these words, we fall under the spell, and Lubezki’s photography of this beautiful garden seems to prove the caretaker’s point. These gorgeous plants, with the blue sky above them, are positively bursting with poignancy. But then the caretaker’s voice fades, and the film cuts hard – violently, even – to a view of a large-scale model of a city transit system, with miniature cars zooming about here and there, as we have seen them do up close earlier in the picture. Bale and Portman are now in a museum looking down upon it. From one man-made microcosm (the Japanese garden) we cut to another; equal aesthetic significance is given to both. Bale and Portman are merely passing through them each, as tourists, as detached observers, wandering through exhibits with no apparent preference for either. Whether we curate and cultivate nature, or miniaturize our own complex structures to see their chaotic inner workings in macrocosm, we are, Malick appears to be suggesting, performing a similar function of compartmentalization and detachment. The cut is breathtaking. It says and suggests so much. It is the whole of the film contained in an instant.

At this point, with Malick producing works faster and faster, and with each successive feature seemingly speaking to a smaller and smaller portion of his audience, I think it entirely possible we may never see another film from him as widely hyped or embraced as The Tree of Life. And after watching Knight of Cups, I am perfectly at peace with that. One of the problems with film criticism – and one I have certainly been guilty of at times – is our desire for everything to be an ‘event,’ for a great director to only produce major works and for our expectations of their artistry to be matched or surpassed every time. This is foolhardy. Filmmakers are artists, and we do not hold such strict standards to other forms of art. Think of a painter, who may produce many works over his or her life, and how silly it would be if we tried to deify every one of their paintings. Some will be worthy of that level of broad audience scrutiny. Others will demand something quieter. And that’s okay; important, even.

As for Knight of Cups, I feel no need to rank this film, to glorify or denigrate it. My only goal is to avoid dismissing it at all costs. I am glad I finally caught up with it, thankful I finally cleared an evening to sit and drink it in. I am grateful I have the opportunity to observe and invest in a work of art such as this, enigmatic and elliptical as it may be. It is beautiful. It is powerful. It is deeply felt and evocatively crafted, even if those feelings and evocations can be difficult to translate. It would not even surprise me much if Malick personally considers this one of his more important works, sees it in some way as a ‘Rosetta Stone’ to unlocking his other features. Certainly, watching it now adds layers to his existing filmography for me, just as it helps me move forward to tomorrow with further clarity and purpose. We cannot fairly ask more of an auteur, nor of his art.

Knight of Cups is now available on DVD, Blu-ray, and digital download from Broadgreen Entertainment.

Follow author Jonathan Lack on Twitter @JonathanLack.