Millennial Anniversary: My 1,000th Published Article – A Countdown of My Ten Favorite Movies

A little over ten years ago, when I was only nine years old, my third grade teacher, Mrs. Heidi Juran, prompted me to apply to write for the Colorado Kids, a Tuesday print inset of The Denver Post written by youth journalists from the state of Colorado. It was the spring of 2002, and in August of that summer, my application was accepted, the first step of a journey that would come to define my life and career over the past decade.

Today, I publish my 1,000th written article. I have long maintained a list keeping count of every article I have ever published, and have double and triple checked over the past week to make sure the count is accurate. You can check the archive for yourself here; there is no mistaking it. You are reading the 1,000th article of my life.

There are many things I feel I should say, many people I should thank or give credit to, but after 1,000 articles, you know who you are. If I have not thanked you in person, I certainly will in the days to come. I did not publish 1,000 articles on my own, and I am eternally grateful to every single person – my family, especially – who helped me get here. If I had known, when I was nine and considering writing for the Colorado Kids, that I would one day be a prolific film critic, accredited journalist of the Denver film press, official member of the Denver Film Critics Society, and recognized critic on aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes all before I turned twenty, I think I would have been overwhelmed with pressure. When I sit back and think about how far this journey has taken me, I feel energized, humbled, and, once again, grateful.

Though I now write for We Got This Covered – which has grown, over the past few months, into one of the top entertainment sites on the web – I wanted to publish my 1,000th article in a space that felt more personal. The old blog, still one of my proudest accomplishments, felt like the right place to celebrate. This post would have been most at home, of course, at the Denver Post’s YourHub, the outlet I feel I still owe the biggest debt of gratitude. I have had the best of both worlds, though, as the main content of this 1,000th article was actually published in my weekly YourHub print column, Fade to Lack, over the past eleven weeks.

Yes, this 1,000th article is an expanded compilation of the eleven-part series I recently published in YourHub, a series that counted down My Top Ten Favorite Films of All-Time. It seems like a fitting topic for the big triple zero.

After the jump, the nature and significance of this countdown project will be explained in greater depth. For now, I will just say that what you are about to read is the basis for Part 1 of my upcoming book, Fade To Lack, which I am announcing for the very first time will be published in print and digital forms later this year.

I hope you enjoy this 1,000th article. I thank you for following and supporting me over the previous 999. And I look forward to what the next 1,000, or even 10,000, may bring.

Read about My Top Ten Favorite Films after the jump…

Introduction

“What’s your favorite movie?”

This is a question I am asked an awful lot.

It is an occupational hazard, I suppose. When one makes a career out of expressing opinions about film, one is bound to receive the ‘ultimate’ question again and again. The irony of the situation is that, precisely because of how many movies I watch, it’s a ridiculously difficult query to answer.

Part of why I have devoted my life to studying this medium is that I adore the thrill of discovering new cinematic experiences. Even when so many films released these days are of poor quality, manufactured on studio assembly lines instead of realized with true artistic passion, I will gladly visit any theatre and watch just about any movie on the off chance that I will find something truly special. If one loves film, there are few greater feelings.

As such, I am always discovering new favorites. If the latest theatrical releases are disappointing, there are always vast unexplored worlds of classics, both widely acclaimed and long underrated, to seek out on home video. My journey through cinema continues every day, and so long as it is ongoing, naming my ‘favorite’ movie, or making a list of the best I have seen, invariably seems like a fool’s errand.

Yet it is, as I said, an occupational hazard. Readers, friends, and colleagues sometimes wish to hear about the best films I have seen, and I must have an answer prepared. Because it is a difficult request, my approach to responding has evolved over time. Sometimes, I believe it means naming the film I most enjoy watching. That, of course, is too broad a field, for I enjoy watching more movies than I can count.

Other times, I wonder if it is best to single out the works I feel stand about all others in a critical sense. This too seems like the wrong approach. Film is too subjective an art form for most viewers, including myself, to start claiming certain movies are among the best ever made. I simply have not seen enough movies to say something so audacious. Even if I continue doing this for the rest of my life, I doubt I ever will.

In recent times, I have found the best approach is to hone in on the word ‘favorite,’ and go where my heart leads me. Favorite, after all, is an easy word to break down. When I think of ‘favorite,’ I envision the films that matter most to me. The movies that matter most to me tend to be the ones that had or continue to have the greatest emotional, intellectual, or aesthetic impact. That impact can, in turn, be measured by considering how each title shaped my tastes, perspective, and love of cinema.

Simply put, my ‘favorite’ films are the ‘movies that made me love movies.’ This is a parameter I can easily grasp, and more importantly, it is one that proves meaningful when I start to consider its deeper implications. Giving examples of the films that shaped my tastes says a great deal about who I am as a viewer, and what I look for in any movie.

Using this guideline, I was finally able to make a ranked list of my ten favorite movies, the first time I have made such a list I felt satisfied with. I have chosen to open this book by sharing the list because I feel it is the most honest introduction I can provide to who I am, both as a film enthusiast and a writer.

The titles descend from number ten to number one, and each is accompanied by a short analytical essay, originally published as a weekly series in The Denver Post during the summer of 2012. After the countdown, an alphabetical list of twenty extra titles considered is provided, for an ultimate collection of my thirty favorite films.

We begin with a film many, myself included, believe to be the greatest children’s movie of all time. Enjoy…

#10 – My Neighbor Totoro

1988; Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

As a student of film, I consider Japanese animation master Hayao Miyazaki my Sensei; no critical appraisal of the medium’s outer limits can be performed without examining his work, and for American audiences used to the rigidity of Hollywood structure, his films are as revelatory as they are rapturous.

The 1988 children’s classic “My Neighbor Totoro” stands near the top of Miyazaki-san’s canon. It is a profoundly simple film, one devoid of plot, antagonists, or contrivances. It depicts fantastical occurrences, but grounds them in some of the purest emotional truths any film has ever offered.

I believe, in fact, that no other film has so powerfully depicted the way children deal with grief. Ten-year-old protagonist Satsuki and her little sister Mei have moved to the Japanese countryside with their father to be closer to their hospitalized mother, and though little is spoken or directly addressed about how the children feel, it is clear her absence weighs on them. There are moments, particularly in the final act, when the sisters’ complex emotions boil over; Mei pouts and cries because she is simply too young to process the enormity of death, and Satsuki breaks down from the pressure of having to play the mature maternal role in her family so fast.

For any viewers who have lost at a young age, Miyazaki-san’s observations are painfully sharp, and I have never made it through the film without shedding a tear. Yet “Totoro” is primarily known as a lighthearted, delightful film, and it is, indeed, the gentler moments where the film’s true brilliance lies.

How could this not be the case, when a character as wonderful as Totoro enters the children’s lives? Totoro is the large, soft, bear-like forest spirit of the title, and he appears when the girls need him most. In the film’s most iconic sequence, he comes to stand with them while they wait for their father at the bus stop, and amuses them by making music with an umbrella.

Miyazaki-san delicately paces Totoro’s appearances for maximum impact; animated with an unrestrained sense of whimsy, each of Totoro’s scenes stand among the most magical moments the medium has ever offered.

Yet even at its most fanciful, “Totoro” is never thematically lightweight. It is Miyazaki-san’s belief, I think, that there are always wonders worth appreciating in this world, wonders so beautiful and healing that none of our problems, no matter how dire, can block out their light. Totoro allows the children a reprieve from their grief by showing them the simple splendors of their own backyard. Miyazaki-san has stated that, in his interpretation, the girls never encounter Totoro again, because they no longer need him. I agree. Through Totoro, their eyes have been opened, and they will never again be closed. Totoro’s role is fulfilled.

Miyazaki imbues a little of himself into all his characters, but in this way, Totoro may be the greatest distilment of his own personality and accomplishments. Through his art, he opens our eyes to spectacles we could never fathom otherwise. Once seen, they can never be forgotten.

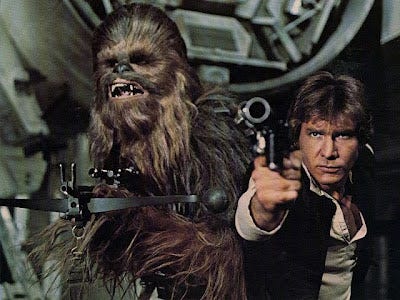

#9 – Star Wars

1977; Dir. George Lucas

In the history of cinema, there are few films we may call ‘perfect,’ and the original “Star Wars” is one of them. It succeeds spectacularly by every critical standard used to judge filmmaking, and back in 1977, it created a few more standards all future sci-fi, adventure, and blockbuster films would be beholden to.

From the moment we enter this galaxy far, far away, it feels like a wholly realized, three-dimensional creation, a world far different from our own yet no less palpable. Within this world, George Lucas tells a story as old as time – a boy leaving home to embark on his journey to manhood – with such energy and flawless execution that the basic hero’s journey is made new again. Each member of the vast cast of characters is just as interesting and endearing as the next, and they all play an essential part in the ongoing conflict. Not a single element is out of line; there are no extraneous scenes, no unnecessary characters or subplots, no poor directorial choices, no misplaced musical cues, etc. etc. This is a wonderful story told to perfection, and it holds up just as well today as it did thirty-four years ago.

That last bit is one of the most amazing things about the film. The story it tells really is just the basic hero’s journey, and after the film broke all box office records in 1977, the formula was popularized and repeated hundreds of times. Yet few – if any – films tell that story better than “Star Wars,” and even fewer movies boast such a fascinating, engaging setting. That is why “Star Wars” stands the test of time, and that is why it remains entertaining no matter how many times it is revisited.

As indicated by the phrase “Episode IV,” George Lucas opens the film by dropping viewers into the middle of a longstanding conflict, and he never once pauses for formal exposition, except perhaps when Ben Kenobi tells Luke about the Jedi Order. The audience is expected to learn the intricacies of this universe through immersion, and that’s what makes things so exciting right off the bat. We want to discover why Princess Leia is so desperate to hide stolen plans inside this strange little droid; we’re desperate to learn about this mysterious empire Darth Vader represents and the opposing rebellion; as soon as Obi-Wan utters the word ‘Jedi,’ we crave more information, and when given glimpses of new locations throughout the universe, from the Mos Eisley Cantina to the Rebel base on the moon of Yavin, we want to spend more time exploring this fantastic universe.

Could there possibly be a better set of characters to take us on this journey? We can all relate to Luke Skywalker, frustrated teenage farm boy desiring more out of life; we would all like the sort of father/mentor figure he finds in old Ben Kenobi; and there are few who would deny a loyal best friend like Chewbacca. There’s Han Solo, the dashing, rebellious rogue who doesn’t care about anything but money, yet clearly has a heart of gold, and Princess Leia, a strong-willed and determined young woman who blasts away every fragment of the typical ‘damsel-in-distress’ archetype. Darth Vader, meanwhile, may be greatest screen villain of all-time, and whose heart isn’t warmed by the antics of R2-D2 and C-3PO?

All the performances are fantastic, though none may be quite so memorable as Alec Guinness, who probably does more than any other actor to give this story a sense of weight, mysticism, and significance.

Every character has an arc, and each arc is fulfilled in a spectacularly satisfying way. I have seen “Star Wars” dozens of times, and I still can’t decide which moment is more fulfilling: Luke putting away his targeting computer to take control of the force and his destiny, or Han coming back to save him at the last minute. There is perhaps no greater indicator of how well Lucas develops these characters than the moment when R2-D2 returns from battle broken and charred, and like C-3PO, we find ourselves hoping against hope that our little robot buddy will be all right.

It is said that music too can be an integral and unforgettable character, but the concept has never held quite as much sway as it does in “Star Wars.” John Williams gifted Lucas with what may be the single best score in the history of a cinema, a bold work of art that stands on its own as a powerful symphony. Williams’ mastery and deployment of themes and motifs is at its absolute height here, and the in-between moments, the less iconic bits of score, are just as beautiful and thrilling.

When Luke taps into the force, Ben tells him he’s taken his “first step into a larger world.” For many cinephiles, “Star Wars” was that first step. It opens one’s imagination to the vast possibilities of filmmaking, and my appreciation of the medium would be incomplete without it.

#8 – Raiders of the Lost Ark

1981; Dir. Steven Spielberg

The previous title featured Harrison Ford. My next pick shall feature Harrison Ford. This film features Harrison Ford at his most iconic.

The repetition is no coincidence. Were I forced to decide, Ford is probably my all-time favorite actor, precisely because of how crucial these three films, each defined by his incredibly appealing work, are to the development of my critical cinematic sensibilities.

Dr. Indiana Jones is, of course, Ford’s most iconic and endearing character, and for good reason. He combines the swagger of Han Solo and the world-weariness of Rick Deckard with an old-fashioned, enthusiastic lust for adventure. Where Ford’s other characters are reluctant heroes, Dr. Jones hunts for action, and he does so for the pursuit of knowledge. If there is intellectual or physical treasure to be gained, he’ll risk whatever the world throws at him, from massive rolling boulders to pits of venomous snakes, all to benefit his beloved museum.

Jones’ high-minded motivations make him unique among action heroes, but it is Ford’s command of the role that places the character in the pantheon. Ford is one of history’s few true ‘movie stars,’ the sort of performer so confident, magnetic, and boundlessly engaging that we will watch him play variations on the same type over and over again.

But Dr. Jones is special. More than any other part across his entire career, one can sense Ford simply having fun in this role, fun that translates in volumes to the audience. Indy isn’t just a character on screen. He’s an icon, a warm role model, even a friend, all because Ford’s performance is so inviting and enveloping.

The movie around him is, of course, practically perfect, and Steven Spielberg deserves similarly limitless praise for his directorial achievements. Has any other film ever combined so many divergent tones so flawlessly, all in the name of having incredible amounts of fun? Spielberg plays with horror, swashbuckling, intrigue, suspense, action, humor, and sweeping romance, sometimes all within the same scene. His command over each tone is such that, though “Raiders” is referential towards movie serials of the forties, the film exists as a glorious island unto itself, a singular experience that plays unlike any adventure before or after it, including subsequent installments in the Indy franchise.

No director can or will ever manage to surpass the incredible action sequences Spielberg crafted here. The set-pieces function like songs in a musical: Giant, expressive, expertly staged outpourings of plot, emotion, and passion. Each is brilliant in conception and execution, and each grows substantially more complex and awe-inspiring as the film moves along. Spielberg is relentless in driving us to the edge of our seat and holding us there until we start developing dangerous heart murmurs.

Yet as vast and epic an experience as “Raiders” is, the film lingers because, like the best of Spielberg’s work, it is also intimate on an intensely human level. Apart from Indy himself, there are plenty of other wonderful characters to enjoy, and the film always follows up its most intense moments with heartfelt, effective character work.

“Raiders of the Lost Ark” is truly an embarrassment of riches, a blindingly entertaining combination of everything the cinematic medium has to offer. It is Ford’s finest hour and Spielberg’s greatest movie, and I am baffled by those who argue otherwise.

#7 – Blade Runner

1982; Dir. Ridley Scott

Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner” is not so much a movie as it is an experience, one that is immersive and enveloping. The world Scott creates is unlike any other ever captured on film, the deepest and most fascinating sci-fi landscape I have encountered.

Brought to life with unparalleled visual mastery, Scott’s realization of a dark, tormented future is impossibly elaborate, rich with detail and expertly, flawlessly designed at every single turn. Yet for all the work Scott and his crew put into crafting this world, they refuse to act as ‘tour guides.’ With little formal exposition and minimal use of dialogue, they expect us to navigate this world ourselves as the story moves along.

That brave employment of subtlety is what lends the film much of its power. My mind wanders while watching “Blade Runner,” pondering everything from the meaning of small, visual details to deeper truths about the characters and their motivations. I think especially hard about the bleak history of the film’s world, and what it possibly says about our increasingly dark present. “Blade Runner” is an entirely different movie each time I revisit it, always a little more captivating than the time before.

Certain elements always remain constant. Harrison Ford’s performance is a staggering work of delicacy and restraint, of quiet emotions and deep-seated pain. Ford abandons his typical, ‘lovable rogue’ persona to sink entirely into the role of Rick Deckard, disappearing into this profoundly broken character so thoroughly it seems they are one and the same.

He is surrounded by plenty of equally wonderful performances, many of them given by actors who never again rose to such heights. Rutger Hauer, in particular, is simply transcendent as troubled android Roy Batty, giving one of the single most fascinating performances ever captured in a science-fiction film. And as Rachel, a ‘replicant’ who has lived for years believing herself human, Sean Young delivers some of the most painful, emotionally honest work I have ever seen.

Vangelis’ beautifully experimental, landmark score is one of my favorites. His calm, hypnotic compositions are as important to the fabric of “Blade Runner” as any other element, and serve as a perfect aural distillation of the film’s remarkable visuals.

Finally, the film’s musings on the nature of humanity, which speak a little differently to each viewer I converse with, always lend the work its strong, beating heart. Many films have discussed the human spirit through the prism of robotic creations, but with a deft, thoughtful hand and boldly evocative implications about the malleable nature of memory, “Blade Runner” says more in minutes than many sci-fi works say in hours.

The film is also notable for its myriad of releases and alternate cuts. The original theatrical version included several elements added without Scott’s approval, including an overbearing narration reluctantly recorded by Ford. These elements rob the film of subtlety, its greatest narrative and thematic asset, and dilute the film’s impact. Scott’s ‘Director’s Cut’ – first assembled without his oversight in 1991, then perfected with the 2007 ‘Final Cut’ – represents the original vision, and is considered by most to be the definite version of the story.

However one sees it, though, “Blade Runner” is remarkable. It pushes towards filmmaking’s outer limits before prodding just a little bit farther, and is an experience all cinephiles must immerse themselves in at one point or another.

#6 – Harry Potter and the

Prisoner of Azkaban

2004; Dir. Alfonso Cuarón

Words cannot describe what J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels mean to me. I read the first book when I was seven, and grew up consuming them feverishly as they were released. Rowling opened my mind to the scope of imagination, the impact of the written word, and the incredible power strong, relatable fictional characters can have on one’s emotional development. I have said it before, and I shall say it again: I would not be the man I am today without Harry Potter. You would not, for starters, be reading these words were it not for Rowling, for it was her work that inspired me to write.

The film adaptations, of course, are one of the major reasons I fell in love with film, and if they never existed, I doubt I would have devoted my life to studying the medium. Alfonso Cuarón’s landmark classic “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” stands high atop its peers not just as the shining pinnacle of this series, but of cinematic adaptation in general.

Cuarón did what Christopher Columbus never could in the first two movies, and what succeeding directors would scramble madly to imitate: He captured all the magic and wonder of Rowling’s Potter on film, visually and emotionally realizing the awe-inspiring creative power of Rowling’s words better than anyone – including Rowling herself – could ever imagine.

Cuarón was not afraid to change and compress the narrative, to alter characters, cut major events, and rework every single scene for maximum cinematic power. This is what any director must do when adapting a sprawling work, of course. What works on page rarely translates to screen without substantial reworking, and the crux of Cuarón’s genius is that, by modifying the story in often radical ways, he comes closer to the spirit of Rowling’s work than any filmmaker before or after.

The film features the single most gorgeous, captivating visual palette I have ever witnessed, one that absolutely floors me with its subtle, immaculately composed beauty. Within each cool-colored frame lies a treasure trove of detail, of magic both quiet and overt, of a bustling, busy, lived-in world falling ever closer towards darkness. With copious assistance from what is, to my mind, the second-best score of John Williams’ illustrious career, the scope Cuarón suggests here is at times overwhelming, just as it should be.

Yet it pales in comparison to the emotional scale Cuarón and his cast achieve. “Prisoner of Azkaban” is Rowling’s best novel for its piercing exploration of the pain familial love – or, more precisely, its absence – can cause us, and Cuarón zeroes in even closer to this central theme. Harry’s life is defined by the love he lacks as much as it is by the affection surrounding him, and “Prisoner of Azkaban” is the turning point, the moment when he becomes conscious of this turmoil and realizes he will have to live with it – not in spite of it – for the rest of his days.

The weight of this story is immense, and thanks to a flawless script, series-best work from Daniel Radcliffe, and achingly tender performances from newcomers David Thewlis and Gary Oldman, the story’s emotions translate even better than they did on page. “Prisoner of Azkaban” is not just one of my favorite films because I love Harry Potter in general, but because of how close this story strays to my own heart, and because of the remarkable execution with which it is realized.

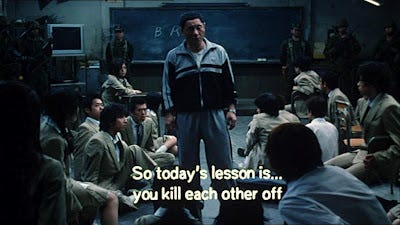

#5 – Battle Royale

2000; Dir. Kinji Fukasaku

Kinji Fukasaku’s landmark action-drama “Battle Royale” finds incredible beauty in one of the darkest premises imaginable: In a dystopian, alternate-history Japan, the tyrannical government demonstrates its control by randomly selecting a class of 42 high school students, aged fifteen, to compete in a battle to the death, where participants must kill one another until only one survives.

Based on Koushun Takami’s 1999 novel, what makes the film adaptation a powerful and profound artistic statement is the highly personal connection Fukasaku had to the material. In his ‘Director’s Statement’ on the film, the filmmaker wrote:

“I immediately identified with the 9th graders in the novel, Battle Royale. I was fifteen when World War II came to an end. By then, my class had been drafted and was working in a munitions factory. In July 1945, we were caught up in artillery fire … We survived by diving for cover under our friends. After the attacks, my class had to dispose of the corpses. It was the first time in my life I’d seen so many dead bodies. As I lifted severed arms and legs, I had a fundamental awakening … everything we’d been taught in school about how Japan was fighting the war to win world peace, was a pack of lies. Adults could not be trusted. The emotions I experienced then – an irrational hatred for the unseen forces that drove us into those circumstances, a poisonous hostility towards adults, and a gentle sentimentality for my friends – were a starting point for everything since. This is why, when I hear reports about recent outbreaks of teenage violence and crimes, I cannot easily judge or dismiss them. This is the point of departure for all my films. Lots of people die in my films. They die terrible deaths. But I make them this way because I don’t believe anyone would ever love or trust the films I make, any other way. “Battle Royale,” my 60th film, returns irrevocably to my own adolescence…”

One can see the themes Fukasaku speaks of all over the movie. They are ingrained into each kill, all the flashbacks, and many of the character interactions, particularly anything involving the administrator of the program, Kitano. When one strips away all the graphic violence, explosions, and set pieces, “Battle Royale” is nothing more than a tale about a group of kids who have been fundamentally let down by the adults in their lives, and must forge independent, resilient identities if they are to survive in such a harsh world. Fukasaku may illustrate these themes in grand strokes, but the film is never anything less than intensely personal, and that is what makes it resonate so strongly.

The core thematic element of Takami’s novel – youth culture pushed to the brink – is also explored. Friendship, love, rivalry, pettiness, and all other fundamentals of teenage society remain, but are heightened, changed, and played with over the course of the battle. An unrequited attraction becomes attempted rape and brutal retribution; past acts of bullying become fuel for murder; the strength of friendship turns into the overwhelming weight of distrust.

These inversions are fascinating – and frightening – to behold, perhaps no more so than in the character Mitsuko, a beautiful outsider who becomes an unstoppable force of nature for the very qualities that left her isolated back in school. For all the students, salvation and madness lie only inches apart, demonstrated most powerfully in the terrifying lighthouse sequence, where a simple mistake leads five best friends to kill each other in a matter of minutes.

“Battle Royale” is a spectacularly violent film, of course, but it’s never exploitative; the gore must be there to illustrate everything I discussed above. As Fukasaku said in his statement, “I make them this way because I don’t believe anyone would ever love or trust the films I make, any other way.” He is absolutely correct. This is a bleak story, and to cushion it by toning down the bloodshed would only reduce its impact. The horror must be absolute for us to truly feel the darkness; only then does the light shine through as powerfully as possible.

For even in this shade, there are moments of unsurpassed beauty in “Battle Royale,” particularly when focusing on the core trio of Shuya, Noriko, and Shogo. The friendship, love, and loyalty these characters develop is as heartwarming as it is heartbreaking – Shuya gives an impassioned speech to Noriko about the need to risk his life that makes me cry every time – precisely because such warmth exists in a world gone so very, very wrong.

Fukasaku’s command of tone, theme, and character is matched only by his authority of pacing and intensity. “Battle Royale” is a relentless experience, with brilliantly designed, interconnecting fights and set pieces that build in force as the film barrels along at a gripping, non-stop pace. Even if it had no thematic concerns whatsoever, “Battle Royale” would still be notable as a top-notch action thriller. It is a masterpiece because Fukasaku finds a way to layer character development and subtext on top of the mayhem at every turn.

Yet the film’s most singular and impressive feat is the beautiful performances Fukasaku coaxes out of his vast, young cast. The actors were almost exclusively fifteen or younger, but their work is uniformly flawless, realistic and emotionally palpable from start to finish. These characters feel like real people, not manufactured creations, and that, more than anything else, is what gives the film such tremendous weight.

Tatsuya Fujiwara absolutely commands the screen as Shuya (and has gone on to lead a successful career in the years since), Taro Yamamoto gives a brilliant ‘man-with-no-name” performance as Shogo, Kou Shibasaki’s complex and nuanced portrayal of Mitsuko is utterly captivating, and Chiaki Kuriyama is so breathtaking in her lone scene as Chigusa that Quentin Tarantino cast her as Gogo Yabara in “Kill Bill.” The rest of the ensemble is not far behind. I have no qualms in saying that this is the best adolescent acting ever captured on film, especially considering the size of the cast.

But to my mind, the best character is Kitano, the class’s previous teacher who has returned to administrate the brutal death program. Played flawlessly by legendary Japanese actor/filmmaker ‘Beat’ Takeshi, Kitano is, to my mind, one of the greatest screen presences in movie history. He can be wildly funny and tremendously scary, but no matter what, there is always a profound sadness underlying his actions, and this is the key to interpreting the film. He truly regrets where society has gone, and though he, like the tyrannical government, would like to simply blame the youth, he ultimately realizes it is more complex than that. His class is merely a mirror, and he is a reflection, and once he comprehends the truth of what he sees, he decides this world is one he would rather not live in.

I have already devoted more words than usual to this great film, and could go on for many more. Masamichi Amano’s gorgeous score – as crucial in relating the story and messages as the script, visuals, or performances – probably deserves a few long essays on its own. “Battle Royale” forever changed how I look at cinema and analyze art, and it continues to impact me on profound levels.

#4 – Princess Mononoke

1997; Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

In Hayao Miyazaki’s “Princess Mononoke,” protagonist Ashitaka is sent forth from his village with a mission to “see with eyes unclouded.” He has been cursed by a spirit rotting of anger, and to heal himself, he will journey the land as a neutral third party, observing with clarity the problems of his world, attaining insight and, in the process, hopefully stumbling upon the cure to his own ailment.

“Seeing with eyes unclouded” is what Miyazaki-san does in all his films, but never so powerfully as in “Mononoke,” where he discusses the infinite complexities of a convoluted world without judgment. Here, he touches upon nearly every theme that has ever interested him – the futility of war, mankind’s relationship with nature, the frailties of the human condition, etc. – with an impossibly deft hand and a staggeringly vast scope.

“Princess Mononoke” is the one true ‘epic’ in animation history, the most ambitious work ever realized through cartoon images. It is a long film, with a complex and multifaceted story; the action takes place on a vast visual landscape, and the emotions it tackles are even broader; the cast of characters is enormous, and nearly all are important; and Joe Hisaishi’s relentlessly gorgeous score is one of the most complex, moving, and sweeping in film history.

Watching “Mononoke” is akin to taking a great journey. It is not an easy experience, nor is it always an uplifting one. But each difficulty leads to increasingly meaningful rewards, and by the end, one’s view of the world shall be considerably richer.

On an immediate level, Miyazaki-san discusses issues of hatred and violence in environmental terms, and displays a profound maturation of his own insight. The sins we commit against our earth, he contends, are never excusable, but they can be understood and overcome if we have the strength to examine our own desires, weaknesses, and the points at which they intersect.

Such ideas are explored through the conflict between a small mining town and the massive surrounding forest. The residents Ashitaka meets are good people, but they take too much from the forest, where local spirits grow restless. These creatures ask for nothing more than room to live, which is the same thing the humans that take from them desire. Neither party’s wishes are unreasonable, yet finding a suitable way to share this world seems impossible. The resulting pressure leads both sides to anger, then to destruction. Terrible acts are executed, and hatred grows stronger every day. Ashitaka, trying desperately to maintain clear eyes and an open heart, is caught in the middle, as is the viewer.

The film’s other central character is San, the “Princess Mononoke” of the title. Do not confuse San’s role with that of the typical ‘Disney Princess.’ Miyazaki-san employs the terminology not to suggest royalty, but the concept of inheritance. Raised by wolves in the forest of the Gods, San is the Princess of nature itself, the inheritor and chosen protector of a much larger world. Ashitaka, a Prince in his homeland, is her counterpart for humanity.

Together, they are the children who shall take on the sins of this broken world, a world that is constantly changing, a world where each generation must learn from the past and work tirelessly to make life a little better for those who come next.

This is the challenge Ashitaka and San choose to confront, hand-in-hand, at the film’s conclusion. It is also, I believe, the central notion behind Miyazaki-san’s entire career. Though he has produced nothing but beloved, classic films, it is unlikely he shall ever make one as powerful and personal as “Princess Mononoke.”

#3 – The Godfather

1972; Dir. Francis Ford Coppola

“The Godfather” is a movie so timeless that many of us inherit it. The film has always been one of my Dad’s favorite movies, and when he first showed it to me, it became one of my favorite movies. The more we watch it together, the more we appreciate it, for we have each other to share it with. Our divide in age makes no difference. It affects us with equal power.

We are both, of course, part of the film’s immediate demographic: Male and American. Though “The Godfather” is not insensitive towards its female characters, it is made from a staunchly male perspective. Though I suspect people of any nationality could enjoy the film for any number of reasons, it is at its core a distinctly American story. Its laser focus is not a detriment, but a fundamental strength. As Roger Ebert likes to say, “movies made for everybody are really made for nobody.” “The Godfather” is made for a specific audience, with a thoroughly authoritative voice, and its greatness extends naturally from there.

Men undoubtedly identify with the film on countless levels, most clearly for its stark portrayal of father and son. We may not all be fathers, but we are all sons, and we are familiar with the sense of compassion and responsibility one feels towards one’s father. Those with children know what it is to be a parent, to desire something greater for one’s children than the life one has lived. And the cycle continues. Even if we have never been part of the Italian mafia, the relationship Michael and Vito Corleone share is so well observed, so emotionally resonant and thematically stimulating, that we empathize on instinctual levels.

“The Godfather” is indeed a family story, and draws much of its staggering entertainment power from the cavalcade of fascinating personalities and performances on display. But in telling the story of one complex, corrupt American family, Coppola achieves something far greater: He tells the definitive story of the ever-elusive American dream.

America was founded on principles of freedom, prosperity, and opportunity, and these are the truths Vito – a good and honest man living a paradoxically wicked life – has lived by to provide for his family. For him, the American dream means sacrificing certain personal opportunities to create a foundation for one’s children, to ensure the next generation can live a life better than their forefathers experienced. This is the allegorical thesis “The Godfather” explores, and as a tale of an immigrant family, it is perfectly positioned to do so.

Despite his career triumphs, Michael’s story is one of immense tragedy. Vito’s actions, intended to give Michael greater opportunity, instead forged a path where his most gifted son would be forever linked to a life of crime, a life much harsher and less forgiving than the one Vito began.

“We’ll get there, Pop. We’ll get there,” says Michael when Vito confesses he always wanted more for his son. It is the film’s most powerful, heartbreaking scene, for Vito is defeated, and Michael’s words are platitudes. The American dream does not function the way he or his father intended. Most likely, it never will.

This is a story that resonates intensely with viewers of this country. It could only be told in America, by a uniquely American filmmaker, about an American immigrant family, and it is so expertly and honestly illustrated that it shall touch anyone who can relate to its themes or characters. It stands, therefore, among the greatest of all American films, and shall always be one of my very favorite movies.

#2 – Back to the Future

1985; Dir. Robert Zemeckis

Robert Zemeckis’ “Back to the Future” is a movie I love so much that I can barely speak about it coherently. The film simply makes me giddy, and no matter how many times I see it – and I have probably watched this one more times than any other movie – my passion for the story, characters, and jokes only grows.

How do I even begin to describe my affinity for a film I adored long before I began writing about movies? Was it Michael J. Fox who initially drew me in, whose wonderful performance made Marty McFly one of history’s most endearing screen protagonists? Or is Christopher Lloyd’s deliriously entertaining Doc Brown the real hook? Characters do not come any more memorable than Doc. Was it their sincere and honest friendship, so unlikely yet so incredibly heartwarming, that originally compelled my attention?

No. Doc and Marty, as magnificently engaging as they may be, only scratch the surface of what “Back to the Future” has to offer. For characters, one cannot forget George McFly, played with such warm, goofy eccentricity by Crispin Glover. Or consider Lea Thompson’s effortlessly comedic work as Lorraine. Her character is at the heart of the film’s silliest scenes, yet Thompson grounds each and every one in something resembling reality, and earns major laughs every time.

Alan Silvestri’s impossibly rousing score is a character in and of itself, as is Hill Valley, a community Zemeckis sells as a believable, lived-in town in not one but two completely separate time periods. The humor is pitch-perfect at every turn, but even though the film is primarily lighthearted, Zemeckis’ direction is so sharp, his staging of set pieces so precise and creative, that he can create endless tension whenever he wants.

And as time travel stories go, “Back to the Future” is a cut above the rest. As someone whose favorite sci-fi concept is time travel, I do not say so lightly. What sets the film apart is that Zemeckis and co-writer Bob Gale saw the fun inherent in the set-up, rather than the darkness most sci-fi stories favor, and they mine that amusement for all it is worth. How strange would it be to meet one’s parents as teenagers? What if your mother actively had the hots for you? Would these experiences break you down, or would they provide invaluable insight into your own life, insight you could use to forge a better future?

“Back to the Future” is a wildly optimistic movie, and absolutely sincere in its joy from start to finish. That glee is infectious; the film’s charms are impossible not to get swept up in. It can be easy for critics, including me, to forget that the primary purpose of film, like most art forms, is to entertain. And I have never encountered a film as wildly, rapturously, joyously entertaining as “Back to the Future.” For that reason, among many others I shall never have enough time or energy to enumerate, it is my second-favorite film of all time.

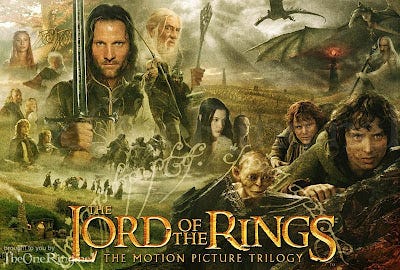

#1 – The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

2001, 2002, 2003; Dir. Peter Jackson

I began this countdown of my all-time favorite films with one specific criterion: This would not be a critical ranking of the ‘best films I have ever seen,’ but a celebration of the “movies that made me fall in love with movies.”

With that in mind, there has only ever been one viable option for the number one spot. Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy is the cinematic experience that ignited my love for the medium, and combined, they are, without question, my favorite films of all time.

Is it a bit of a cheat to put three movies in the number one spot? Perhaps, but then again, Jackson and his collaborators also ‘cheated,’ in a sense, when they decided the best way to adapt J.R.R. Tolkien’s sprawling epic was to do so over the course of three movies, shooting everything at once and doling the finished product out to audiences over the most exciting three-year period in modern movie history. No one had ever attempted anything like it before. Until Jackson recently decided to produce “The Hobbit” as a trilogy, no one has tried it since.

“The Lord of the Rings” was an incredibly audacious project, and ever since the release of “The Fellowship of the Ring,” the trilogy has inspired proportional levels of disbelief. I vividly remember watching “Fellowship” in theatres for the first time, alongside my father in December 2001, and finding it impossible to accept that I was watching a mere movie. How could the magic Jackson and company captured be confined to celluloid? These were not actors prancing around in costumes on manufactured sets. This was Frodo, the real Frodo, and the real Sam, and the very real, altogether wonderful Gandalf, standing tall amongst the rest of a tremendously palpable Fellowship, venturing through a Middle Earth so tangible and authentic one could practically smell the grass, and feel each gust of wind, and mourn deeply for every single loss.

In that theatre, on that night, watching that movie at the age of nine, my life was forever changed. This was the power of film. These are the places the medium could take us, if the director’s vision was strong and the cast and crew’s dedication absolute. I had never seen anything remotely like “The Fellowship of the Ring.” Eleven years and hundreds of movie reviews later, I still never have.

Excepting “The Two Towers” and “The Return of the King,” of course. Part of Jackson’s genius in crafting these films was his ability to make each installment a cohesive, satisfying experience, even as each remained part of a greater whole. He never left us wanting, but inspired an aching desire for more, a subtle but important distinction. Each film works spectacularly on its own, with separate climaxes and emotional arcs that resonate powerfully even in a vacuum.

But it wasn’t until “Return of the King” was released, and one could finally watch the trilogy in succession, that the project’s true brilliance could be understood. No one had ever used film to tell a story this sweeping before. No one had ever taken twelve whole hours (in the definitive Extended Editions, at least) to develop a vast ensemble of characters, or to tell the story of a nation facing destruction, or to relate deeply thoughtful themes about the horrific nature of war and the uplifting power of friendship. “The Lord of the Rings” did it all. As an emotional cinematic experience, especially during the overwhelmingly powerful climax, it is unsurpassed, for no other film has ever spent this much time so expertly drawing us in to its world.

Nor has any composer ever had reign to compose such a masterpiece as Howard Shore’s awe-inspiring multi-part score. It is unquestionably the greatest score in film history, one that functions as completely as a stand-alone symphony as it does accompanying the movies. Shore crafted more themes than I can count, each of them as beautiful as the last, and never rested on his laurels. Each subsequent chapter expanded masterfully on the elements of its predecessor, resulting in the impossibly rich array of sonic poetry that defines the final hour of “The Return of the King.”

“The Lord of the Rings” is a narrative triumph, of course, because Tolkien’s book is a masterpiece, and Jackson adapted it smartly and efficiently at every turn. As a character piece, though – and this is where the films excel most impressively – Jackson’s adaptation consistently exceeds the author’s original work. Where Tolkien’s characters were relatively static, Jackson’s are complex and malleable, susceptible to the same weaknesses we all fall pray to, capable of the same meaningful growth and development humans are wont to experience.

As a result, none of these characters feel distant. Their flaws make them immediately accessible, their triumphs transform them into heroes, and their complex personalities make them endearing. Discussing each of them in any sort of detail would be a fool’s errand, requiring several articles of excessive length. I shall simply say that Gandalf is my favorite screen character of all time, with Ian McKellan giving the warmest, most amazing performance I have ever seen. Aragorn, the utterly unique, impossibly compelling action hero, is a close second.

If I had never met these characters, and never followed them on a journey through cinema’s most gorgeous and imaginative landscape, I doubt my relationship with film would be as significant as it is today. “The Lord of the Rings” changed my life. It inspired me, and every time I revisit the trilogy, that inspiration is reignited. They are my favorite films of all time, and I do not imagine that changing any time soon.

Runners-Up: Twenty Additional Favorites

Note: Presented alphabetically, these twenty titles (or, in some cases, groups of titles) are the ones I felt pained to leave out of the Top Ten, and bring my list of favorites up to Thirty, which seems like a nice round number at which to cap things. Enjoy.

Black Swan

2010; Dir. Darren Aronofsky

Blazing Saddles

1974; Dir. Mel Brooks

The Darjeeling Limited

2007; Dir. Wes Anderson

The Dark Knight

2008; Dir. Christopher Nolan

Death Note and Death Note: The Last Name

2006; Dir. Shusuke Kaneko

Die Hard

1988; Dir. John McTiernan

Fantasia

1940; By Walt Disney and Leopold Stokowski

Inception

2010; Dir. Christopher Nolan

It’s a Wonderful Life

1946; Dir. Frank Capra

Kingdom of Heaven

2005; Dir. Ridley Scott

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl

2003; Dir. Gore Verbanski

The Collected Works of Pixar Animation Studios

1995 – 2010; Dir. John Lasseter, et al.

The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town

2010: Dir. Thom Zimny

Rocky

1976; Dir. John G. Avildsen

Seven Samurai

1954; Dir. Akira Kurosawa

Spider-Man 2

2004; Dir. Sam Raimi

Spirited Away

2001; Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

The Collected Works of Quentin Tarantino

1992 – 2009; Dir. Quentin Tarantino

Whisper of the Heart

1995; Dir. Yoshifumi Kondo

The Wizard of Oz

1939; Dir. Victor Fleming

Thank you once again for following me over 1,000 published articles. You, the reader, are the reason I can continue to do what I love, and I will always be thankful for having the opportunity to write and to share 1,000 of these. Let us make the next thousand even better.