Miyazaki Madness, Part 15: "The Boy and the Heron" sees the return of a master

The best film of 2023, and the end of our series

On Thursdays, I’m publishing reviews of classic movies, including pieces that have never appeared online before taken from my book 200 Reviews, available now in Paperback or on Kindle (which you should really consider buying, because it’s an awesome collection!). In this series, we’ve been examining the filmography of my all-time favorite movie director, Hayao Miyazaki! And today, we wrap back around to his most recent film, and the one that directly prompted this series in the first place, The Boy and the Heron. This is the same review I published six months ago, but for the sake of completion, I thought we should include it here to round off the series. Enjoy…

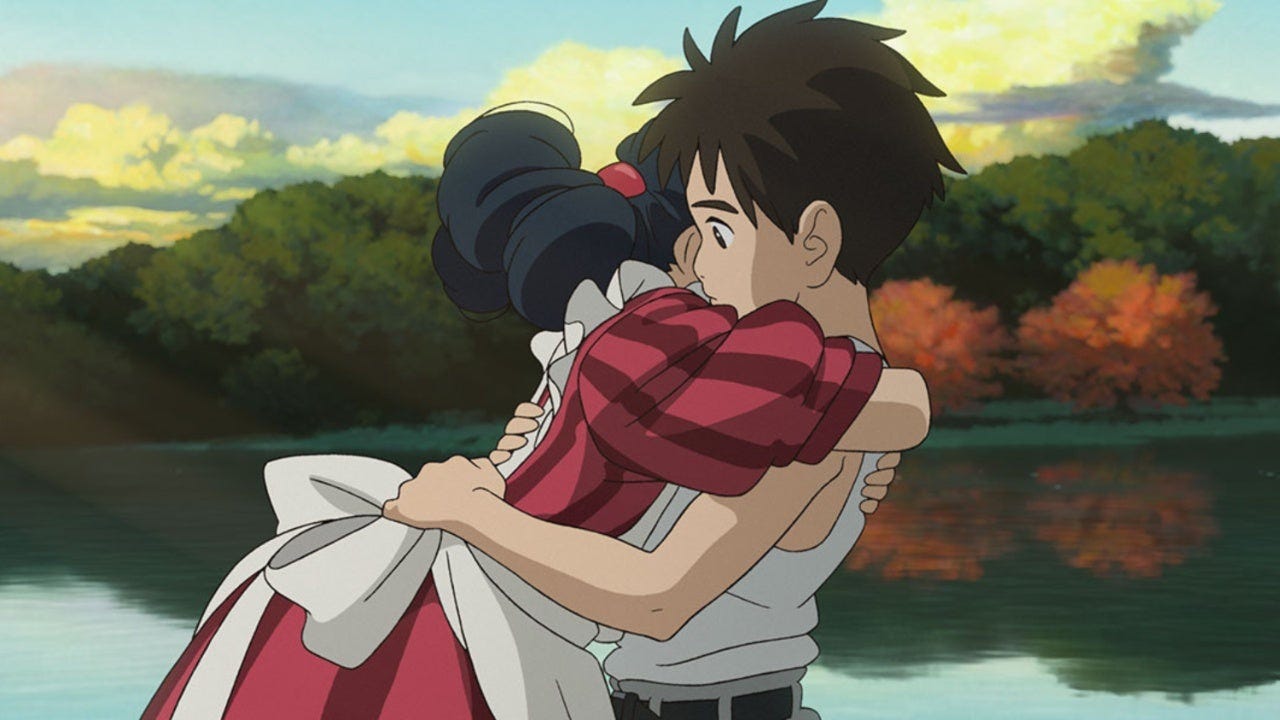

The Boy and the Heron

2023, Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Originally published December 7th, 2023

For the last six weeks or so, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about death. I don’t know why. Thoughts, images, and fears have come unbidden into my mind when it is otherwise still and empty, keeping me awake at night and making me anxious during the day. Where do we go when it’s all over? What does it feel like? What is on the other side? If there is nothing more, what is that like, and what does it mean for our existence here? Where were we before we were born? If life is temporary, a brief spark of light amidst an infinite ocean of darkness, what is its purpose? How does one live when these fears gnaw at us so greedily?

I think Hayao Miyazaki has been contemplating these questions too, and he has had many more decades to do so. The Boy and the Heron, his first film in ten years, is about many different things, but it is at its core a fable about death – about what we leave behind, about the worlds we live in and the ones we create, what lessons we want to leave to those we love and what we hope for them when we are gone, and what those who survive have to feel and work through and push past as they discover how they will wield the light they have been passed. It is a message from a grandfather to a grandson, from someone nearing the end to someone still close to the beginning. Its plot is oblique and its sense of internal resolution or denouement either minimal or nonexistent; the storyteller trusts the listener to fill those pieces in for themselves. In Japanese, the film’s original title – Kimitachi wa dō ikiru ka – is a question: How Do You Live? The film itself should be seen the same way: a provocation to further thought, to reflection, a torch passed from filmmaker to viewer. Where and how we shall cast its light is up to us.

The Japanese title is borrowed from Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel, a classic of Japanese children’s literature that is one of Miyazaki’s lifelong favorites. It’s easy to see why; reading it feels like uncovering the rosetta stone for his entire way of thinking. Yoshino’s How Do You Live? Is a book about growing up and learning, and learning how to learn, and how to think critically and holistically, and in so doing how to live among others; its underlying themes would be broadly applicable to every movie Miyazaki has ever made, and its fundamental gentleness of tone and spirit, of not just seeing the world through a child’s eyes but celebrating and encouraging that perspective of discovery and self-formation, is Miyazaki’s North Star as a storyteller. Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? is not at all a narrative adaptation of Yoshino’s book, though the protagonist reads it in one important scene. The film is instead something of a reaction to Yoshino’s work, an adventurous meditation on the many lessons the book imparted to the filmmaker, and how they have informed his work, and how he has internalized them eighty years later. Where Yoshino’s How Do You Live? is straightforward and clear, a story told plainly with its lessons imparted directly, sometimes through epistolary letters from the protagonist’s Uncle, Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? is challenging and opaque, a story resistant to familiar narrative shapes, its lessons ambiguous and its ideas open ended.

This is, without question, the strangest film Hayao Miyazaki has ever made, and perhaps the oddest in the entire Studio Ghibli filmography. I think it will throw many people for a loop, myself included; its rhythms are not those we have come to expect from Miyazaki, who has resolutely been something of a classicist across his career. His mentor and partner Isao Takahata was the one who experimented with narrative and form, in boundary-pushing works like My Neighbors the Yamadas or The Tale of the Princess Kaguya; Miyazaki told stories, clear and vibrant and obviously his own, evolving and honing his style over time as any artist does, but never breaking and remaking it like Takahata so often did. Takahata died in 2018, and I wondered sometimes, while watching The Boy and the Heron, if some of his spirit rubbed off on Miyazaki after he passed on; there is an adventurous approach to storytelling here, a willingness to break and bend the narrative shapes we expect of Miyazaki, that took me aback – and moved me greatly.

The film’s protagonist, Mahito, is Miyazaki’s most stoic hero; in the film’s opening scene, he loses his mother to one of America’s fire-bombing campaigns in Tokyo during the war. The sequence is visualized as a nightmarish haze of bending, shimmering lines, every character and background element made unstable and porous, the world exploding around them and from within; it is the most jarring stylistic rupture in Miyazaki’s entire filmography, standing in stark contrast to the patient, slow-burn rendering of the Great Kantō Earthquake in The Wind Rises. That event was outside Miyazaki’s living memory; the firebombings, he has said and written about, are his earliest recollections. That they are sketched here as a cry from the depths of the unconscious, a traumatic roar billowing under the surface waiting always to lash out, is striking. Of course, Miyazaki is part of the last generation alive on earth who remembers these events, and there is a tremendous pathos and tenderness to the early scenes simply depicting life amidst the war, the mundanity and the tragedy, the tools of animation here utilized to crystallize memories that will, before long, be lost to mortality and time.

This is Mahito’s starting point, and the film’s, beginning from a place of real and remembered and immense pain, collective and historic. It remains there throughout, but just under the surface, for Mahito keeps it all buttoned up tightly. His face is still and his movements precise, but we can still feel it all roiling underneath. Exactly once does he let that trauma overtake him, in what is I think the most shocking, impactful, and graphic moment of violence in Miyazaki’s filmography. Emotional scars become physical, and live on Mahito’s otherwise placid visage for the rest of the film.

Emotion is thus sublimated throughout much of the picture – but emotional logic abounds. The Boy and the Heron is the most Miyazaki has ever fired from the hip, has imagined straight onto the canvas as though pictorially transcribing a dream; narrative and geographic and diegetic coherence is prioritized far, far beneath the whims of the imagination. Miyazaki’s features have sometimes had moments of breakage, where the reality we have been watching slips away and we enter a poetic land where logic gives way to lyricism; I think of the plane graveyard in Porco Rosso, a line of lost pilots stretching on to infinity; or the journey to the Sixth Station in Spirited Away, where Chihiro takes a train across an eerie and unending ocean; or the mountainside cottage where a young Howl is visited by a star in Howl’s Moving Castle, a place that seems to exist in a dimension all its own. Moments like these can only be read symbolically, emotionally; we react to them like we do a piece of music, and Miyazaki certainly leans hard on composer Joe Hisaishi to bring these dreamscapes to life. If I were to try describing The Boy and the Heron in relation to Miyazaki’s canon, I would say it feels like one of these moments stretched out to feature length, its main character entering a series of these haunting, sublime expanses and journeying there for the whole of the run-time.

As singular as the film feels to watch, there are pieces of every other movie Miyazaki has ever made tucked away in here. The aforementioned plane graveyard from Porco Rosso is echoed here in a procession of sailboats stretching across an endless ocean like the one from Spirited Away; a Parakeet King swashbuckles in a high tower like Lupin and the Count in The Castle of Cagliostro; Mahito strings and fires his bow, sometimes with the arrow itself taking over, akin to Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke; when he enters the other world, he passes through a dark stone tunnel, as Chihiro does in Spirited Away. Echoes of Miyazaki’s career abound, defamiliarized through a film that moves in such a different fashion than those earlier works. The Boy and the Heron is something of a career summation, in the sense that it feels like we have stepped into the director’s subconscious, are exploring the corridors of his imagination, sometimes glimpsing familiar sights, often seeing strange new combinations.

And what images these dreams are made of! It is entirely possible The Boy and the Heron is the single most lavish animated film ever mounted, a proclamation that will only seem hyperbolic until you see these images unravel for yourself. The sheer number of frames of animation drawn for every character and on-screen element is staggering, the fluidity and ferocity of every movement genuinely astonishing. That it took seven years to animate is unsurprising when watching the finished product; producer Toshio Suzuki has said he believes it may be the most expensive film ever made in Japan, and the grandeur and complexity of the imagery gives me no reason to doubt him. There are so many backgrounds and settings, so many bold deployments of color and motion. Water and blood alike explode in globs of visceral tactility. Viewers who take particular pleasure in Ghibli’s iconic depictions of food and eating – like the bacon and eggs in Howl’s Moving Castle or ramen with ham in Ponyo – will be treated to what I feel comfortable calling the most luxuriously drawn depiction of toast with butter and jam in the history of the cinema. Perhaps most of all, the Heron of the title – at least when he is in bird form – is a marvel of physicality and momentum; and he is, in fact, just one bird among many lovingly animated with an overwhelming surfeit of detail. There are no flying machines in this movie, though individual pieces of unmade airplanes are seen; instead, there are organic flying creatures galore, of all shapes and sizes. Birds abound, as though they are the natural inhabitants of Miyazaki’s imagination; even their droppings are animated with precision.

Miyazaki’s longest-serving collaborators are increasingly few, as time takes its toll; this is, for instance, his first film without the great Michiyo Yasuda in charge of color design, as she passed away in 2016. The legendary Kazuo Oga’s name appears among the list of background artists, though, and longtime Ghibli regulars fill the senior ranks, like Yōji Takeshige on Art Direction and Atsushi Okui as Director of Photography (in animation, the person responsible for compositing all the disparate layers into cohesive images – Okui is a master at this). And of course, there is Miyazaki’s stalwart, essential partner Joe Hisaishi composing the music. This is not his most rousing or attention-grabbing score, yet I feel he and Miyazaki have never been more perfectly in tune with one another, the composer’s gentle and plaintive piano work quietly tapping into those powerful emotions simmering beneath the surface, reflecting the way they always seem about to boil over. It is a remarkable marriage of music and imagery, though one should expect nothing less from this team.

I do not know how to properly express just how extraordinary it is a film like The Boy and the Heron even exists. A purely auteurist vision, boldly and brazenly and defiantly singular. The non-Miyazaki movie I thought most about while watching, weirdly enough, was David Lynch’s Inland Empire – also a film where its inimitable director gave himself over most fully to experimentation and surrealism, let the distinctions between fantasy and reality, dream and awakening, become porous to the point of invisible, crafting an odyssey towards an unspecified destination. The Boy and the Heron is more cogently narrativized than Lynch’s film, and much less aesthetically challenging (Lynch’s movie is infamously low-fi, where Miyazaki’s is epochal in its production values). But I found myself musing on similarities in the slow burn confidence of the director’s artistic exploration here, the storyteller trusting, at this well-developed point in his career, that his audience will be along for the ride, will follow and have faith in the journey even when it isn’t clear where we’re going. That supreme air of confidence pervades The Boy and the Heron; even when the story is at its most oblique, there is an overwhelming sense that a master is telling it.

Still, this is without question one of the strangest films that has ever enjoyed a wide theatrical release in the United States, foreign or otherwise. It is amazing it exists at all, let alone on the scale it does, and I am overjoyed that American distributor GKids is giving this the push it deserves (the subtitles are masterfully done, moved around the lower third to obscure the animation as little as possible from shot to shot; I have not yet seen the English dub, but by all accounts it is respectful and accomplished in its own right). I’m very curious to see what wider reactions the film will prompt here, given how unconventional it is even by Miyazaki’s own standards. The sold-out opening night crowd I saw it with was very much engaged, but I heard some frustrated mutterings as the credits – set to an absurdly gorgeous song by Kenshi Yonezu – began to play.

For my part, I have only just begun to grapple with this film, and I have no idea if the thoughts presented in this review are even coherent. Hayao Miyazaki has been my favorite director since I was young, the one who inspires me and my work the most; any film he makes would be a lot for me to take in, but The Boy and the Heron is challenging and thought-provoking on an entirely different level. I am in awe of it, and I suspect it is a film I’ll keep chewing on for the rest of my life. If Miyazaki still has more films in him before his life comes to a close, God only knows what heights they will reach for.

NEXT WEEK: A new series begins…

All Miyazaki Madness Pieces:

If you liked this review, I have 200 more for you – read my new book, 200 Reviews, in Paperback and on Kindle: https://a.co/d/bivNN0e

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our podcast about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com