My 12 Favorite Films, and Where to Stream Them (Part 2 of 2)

Revisiting my personal cinematic canon for 2020, and for shut-in season

This is Part 2 of my 12 Favorite Films piece; turns out Substack has a limit on how long these posts can be, so I had to cut it in half! Both should have arrived in your inbox around the same time, so make sure to take a look at Part 1, with the first 6 films, before moving on to Part 2, with the final 6 films. Enjoy!

Sansho the Bailiff

(Japan, 1954; Dir. Kenji Mizoguchi)

Why is it on the list? Because Sansho the Bailiff left me a shaking, emotionally scarred puddle in my Freshman Intro to Film class – I was probably the only one of the 100+ students who liked it, and yes, the rest of them thought the kid crying in the front row at this old Japanese movie was a weirdo – and I haven’t been able to get it out of my head since. A parable about mercy, suffering, loss, and morality built on the bones of an ancient folktale, Sansho the Bailiff tells the story of a noble family torn apart in feudal Japan, with the mother sold in prostitution and the children into slavery under the cruel eye of the title character.

It is a story about doing what is right and living with compassion no matter the severity and challenges of one’s circumstances, and it is, perhaps, the most effective piece of emotional devastation I have yet encountered on film. Mizoguchi, alongside Kurosawa and Ozu, is one of the undisputed masters of Japan’s cinematic Golden Age, and while there is plenty of debate over which of his immeasurably rich late-period works is his masterpiece, Sansho, for me, stands tall above the rest. It’s all there in that jaw-dropping final scene, when mother and son are finally reunited, and the weight of the film’s carefully constructed emotional house of cards comes crashing down upon the viewer. It destroyed me when I was a Freshman in college, and I frankly only find it more affecting as the years go by.

Availability: Currently streaming on The Criterion Channel. Also available for digital rental or purchase on iTunes and Amazon.

A Scene at the Sea

(Japan, 1991; Dir. Takeshi Kitano)

Why is it on the list? Because Takeshi Kitano – oddball multi-hyphenate actor/auteur extraordinaire – is one of my very favorite filmmakers; because last time I did this exercise I picked his wonderful breakout masterwork Hana-bi (1997); and because this time, I thought I would try to one-up myself on esoterica and pick a film that is well and truly unknown and uncelebrated, and which is so entirely unavailable in the United States that you will have to pony up for an imported Blu-ray from Japan or the United Kingdom if you want to see the film in anything resembling decent quality.

But really, it’s because in my heart of hearts, this unsung, almost entirely unknown and under-distributed out-of-character early work by Kitano is a deep and abiding personal favorite of mine. A Scene at the Sea – or, as its poetic Japanese title translates to, That Summer, the Quietest Ocean… – was Kitano’s third film as a director, and the first in which he did not appear on screen (under his acting pseudonym Beat Takeshi). It is a remarkably simple story about a deaf garbage collector who decides to learn how to surf, with the help of his stalwart, also deaf girlfriend. It is about perseverance, and young love, and obsession, and it is also one of the great films about community, as the group of mocking nay-sayers who doubt our protagonist eventually become his friends and cheerleaders. It is a quiet film, mostly bereft of dialogue, with the sounds of the ocean and a truly magnificent, synesthetic score by the great Joe Hisaishi – in the first of several great collaborations with Kitano – forming the majority of the film’s soundtrack. It is a film of spaces and pauses and soft visual poetry. Like many Kitano films, its premise sound better suited for a short film; but then, you would not get the depth of feeling or of detail, the beautiful sense of time passing, or the gradual, glacial shifts in character and mood that define his work at its best. As seen in his most famous Yakuza and Yakuza-adjacent works like Violent Cop (1989),Sonatine (1993), and Hana-bi, there is no filmmaker as singularly capable as Takeshi Kitano of combining gritty crime violence and transcendent meditations on the human condition. A Scene at the Sea, though, is exclusively the latter, fully revealing what a gentle, thoughtful, melancholy heart beats beneath this strange director’s extraordinary work.

Availability: There is none. Not digitally, not for streaming, and not legally in the United States or, frankly, most of the world. This is one that, to the best of my knowledge, is only legally available on physical media. If you’re in North America, your best bet is to import the Blu-ray from Amazon Japan; it has English subtitles (not that you really need them for this film), and we share a Blu-ray region with Japan, so you won’t need a region-free player. The film is also available on Blu-ray in the UK, again with English subtitles, though it’s Region B, so if you live outside Europe you’ll need a region-free player. I might normally end with a joke here about just pirating the movie instead, but frankly it’s so obscure I don’t know if that’s even possible. Just buy the disc – shipping from Japan is amazingly fast and the country has relatively few cases of Coronavirus – and trust me that it’s worth it.

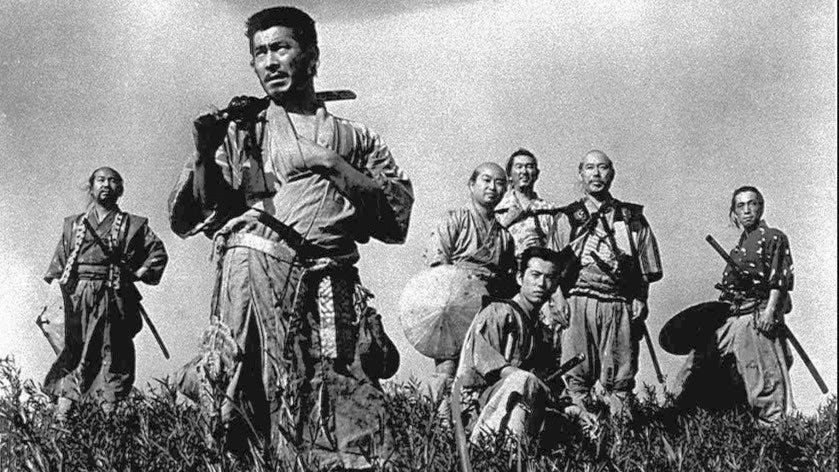

Seven Samurai

(Japan, 1954; Dir. Akira Kurosawa)

Why is it on the list? Because Kurosawa is The Master, and Seven Samurai is his masterpiece. You will never feel 3.5 hours fly by faster, and you will never be so simultaneously moved, thrilled, and roused. If you somehow haven’t seen it, I know for a fact you now have the time. Get on it.

Availability: Currently streaming on The Criterion Channel. Also available for digital rental or purchase on iTunes, Amazon, YouTube, and Vudu.

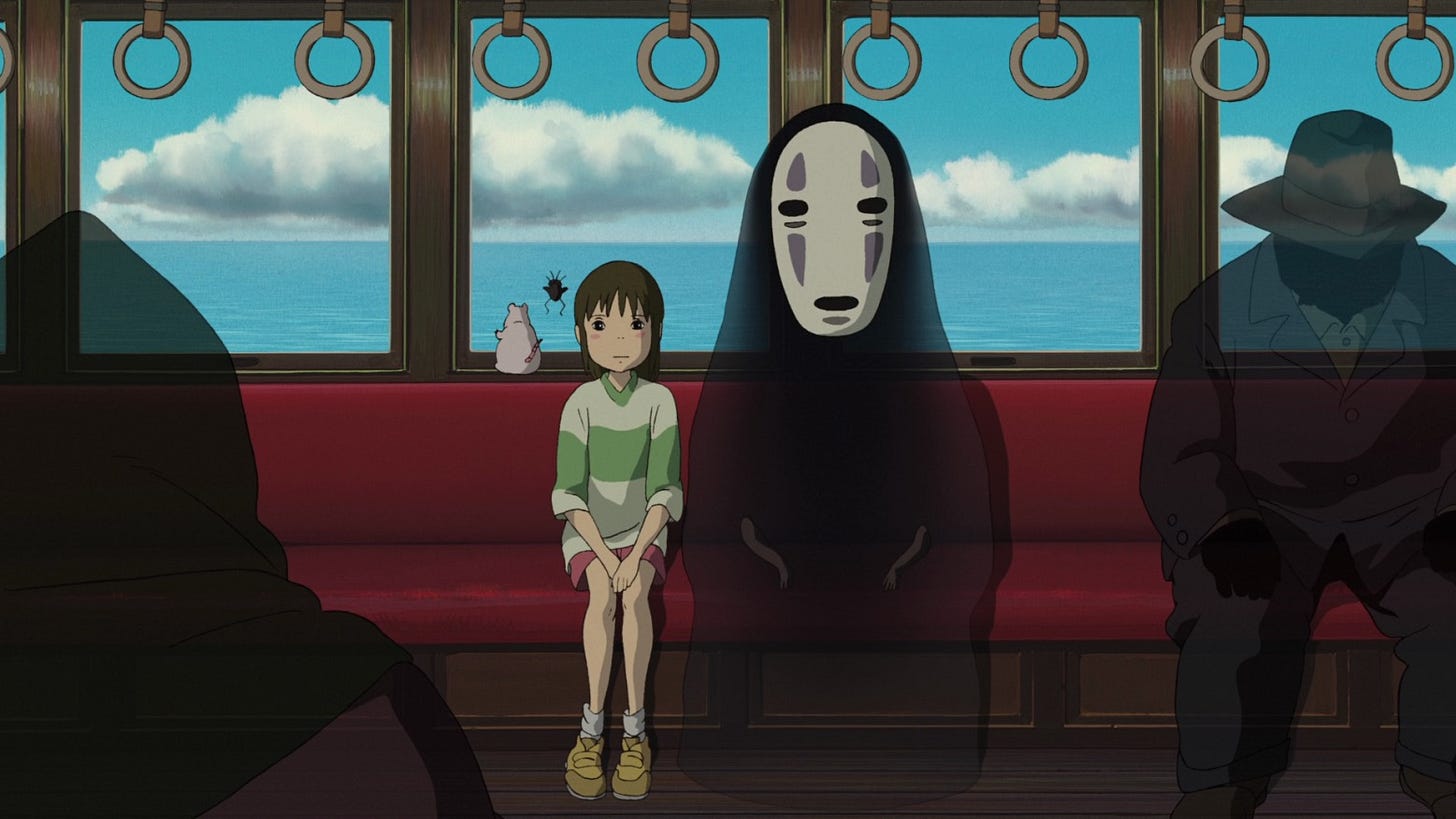

Spirited Away

(Japan, 2001; Dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Why is it on the list? Because of this scene:

I could tell you more. I have in the past, on the podcast and elsewhere. I’ve even given guest lectures at the University of Colorado on this film multiple times. But those 3 minutes happen to be my single favorite sequence in the history of cinema, and I am not going to pretend I can come up with a better testament to why I love this film so dearly. Hayao Miyazaki is, of course, a hero to me. I love every single one of his films passionately, and I could just as easily put Laputa (1986) or Porco Rosso (1992) or Princess Mononoke (1997) or Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) on this list and be satisfied with the choice, because I love those films as much as anything else.

But they don’t have that scene. That beautiful, quiet, melancholy, contemplative scene, scored to the best 3 minutes of music in Joe Hisaishi’s incredible, singular career. Spirited Away has that scene. There are many reasons why the film belongs on this list, but that scene towers above them all.

Availability: Available for digital purchase on iTunes, Amazon, YouTube, and Vudu. It will also be streaming as part of the Studio Ghibli collection on HBO Max when the service launches in May 2020. In all cases, you can either watch the film in its original Japanese with English subtitles, or dubbed into English. I am typically a purist about these things, but Spirited Away happens to have one of the best English dubs ever produced, and I feel fully confident recommending it in either form.

A Touch of Zen

(Taiwan, 1971; Dir. King Hu)

Why is it on the list? Because every time I watch a film by King Hu, I find myself thinking, “is this the most preternaturally gifted filmmaker I have ever had the privilege to watch work?” Hu’s small but dense filmography has only recently become available in the West in good quality, after a series of restorations undertaken by the Taiwanese Film Institute have made their way to Blu-ray in the UK and US, and they are by far the greatest cinematic revelation I have had in recent years. A pioneer of the Wuxia film – a term which comes from the Chinese literary genre about martial artists in ancient times – Hu, who started in Hong Kong but primarily worked in Taiwan, was a huge influence on later Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and Chinese filmmakers, from Tsui Hark to Ang Lee, and while his innovations have been widely borrowed and built upon, none of his successors are a substitute for the genuine article. In films like Come Drink With Me (1966), Dragon Inn (1967), and The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), Hu combined vivid, archetypal characters – including a number of strong female leads, a Wuxia literary tradition that hasn’t always been mirrored on film – wry humor, a rigorous development of space and never-ending masterclass in blocking, outstanding action choreography, and the boldest, most perception-altering use of editing in narrative filmmaking since the days of Soviet montage masters like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov. Legend of the Mountain (1979), a nearly uncategorizable three-plus-hour mind trip that can best be described as Chinese gothic horror, contains a sequence that I would count as the greatest, most creative, and most arresting piece of narrative film editing since Man With a Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929).

A Touch of Zen is Hu’s masterpiece, and it contains all these qualities and more. So singularly ambitious that it was originally released in two parts – with filming for the second installment still underway as the first arrived in theaters – the three-hour compiled version that survives today is a winding, unpredictable martial arts epic of uncommon patience – it takes over an hour for anyone to draw swords – and even more striking spiritual depth. It begins as the story of a small-town scholar and the mysterious, disguised noblewoman who seeks refuge in his seemingly haunted village, and ends as nothing less than a Buddhist parable about enlightenment. Along the way, Hu sketches incredible characters and delivers sequence after sequence of virtuoso masterwork, from the scholar’s initial, frightening journey through a haunted estate, to a mid-film set-piece in a bamboo forest so electric every Wuxia filmmaker since – including Hark, Lee, and Zhang Yimou – has paid homage to it, to the trippiest and most jaw-dropping finale in the history of martial arts filmmaking. To me, A Touch of Zen is unquestionably one of the greatest achievements in the history of cinema; that it is also one of my favorites almost feels like an afterthought.

Availability: Currently streaming on The Criterion Channel. Also available for digital rental or purchase on iTunes, Amazon, YouTube, and Vudu.

The Tree of Life

(United States, 2011; Dir. Terrence Malick)

Why is it on the list? Because there is no film I had a more fraught or bizarre path to falling in love with, and no film that has taught me more about how to open one’s mind and heart to the complexities and surprises of this medium. The first time I saw it, in theatres in the summer of 2011, I hated it. I wrote:

“For all its so-called “meaning,” for all the style and craft and ‘grace’ on display, it merely numbed me for over two hours, and left me completely cold afterwards. This is an example not of style overwhelming substance, but of style beating substance into submission and then running a long, long victory lap.”

It was as dismissive a review as I had ever written or published. But as the months went by, and I thought I was done with The Tree of Life, it became clear that The Tree of Life was not done with me. This film I had found pretentious and overwrought kept entering my thoughts, and when we learned my father’s cancer had returned later that year, the one movie I felt I needed to watch to help understand the world and my feelings was, for reasons I could not understand, The Tree of Life. So I rented it on my PlayStation 3, screening it on my little 26-inch monitor while sitting on my dorm room bed, and by the end, the movie had left me a weeping, frayed nerve. I had fallen in love with it. In the piece I published afterwards, I wrote:

“The beauty on display often cannot be explained. The images are edited together in a stream-of-consciousness style, and when one tries to break down their order or meaning logically, one comes up empty handed. It is an experience of pure emotion, and if you let yourself go, you will be swept up in the beauty, comprehending the story and message on an instinctual, ethereal level. “The Tree of Life” doesn’t just feature the most controlled, precise, and visually powerful images of 2011, but uses the cinematic medium to its fullest advantage.”

Clearly, this was quite the turn. I had never had this kind of experience with a movie before, rejecting it at first and falling in love with it later. It is something that has happened to me many times in the years since. I learned to listen to that inner voice, that voice that told me when I wasn’t yet done with a film, even when – especially when – I had disliked or dismissed it on first viewing. It was learning to trust that voice, to give films another try when something I could not put my finger on pulled me towards them, that led me to fall in love with Terrence Malick’s entire body of work, and which led me back, as all roads inevitably would, to The Tree of Life, again and again, confirming that experience was not just a fluke, but a life-changing experience. This is, indeed, one of my very favorite movies. I can watch it in whole or in parts and feel like I am having a cleansing spiritual experience, one that centers and stabilizes me, and in which the film always feels like a slightly different entity than the one I encountered before. Not all movies make themselves easy to love; having to work for it – or, more precisely, to work with it – sometimes makes the love all the more profound.

Availability: Available for digital rental or purchase on iTunes, Amazon, YouTube, and Vudu. The DVD and Blu-ray sets released by The Criterion Collection additionally contain an Extended Version with an additional 50 minutes of footage, bringing the run time to over 3 hours. This version is only available on that physical edition, but I prefer the Theatrical Cut and consider it the definitive version of the film. The extended cut is a compelling curiosity, but should be seen only after digesting the original version.

So those are my favorites! Tell me about yours in the comments, and let me know if you give any of these a try.