Review: "A Nightmare on Elm Street" still feels revelatory at 40

Movie of the Week #11 makes us afraid to go to sleep

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week for paid subscribers. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

This might be a surprise for readers or podcast listeners who have only gotten to know me in recent years, but I never watched horror movies much as a kid, or even as a young adult. My parents did not like (or really even approve of) them, so they just weren’t part of my media diet growing up, outside of a few standouts like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining that slipped through the cracks (and which have been retconned as ‘psychological thrillers’ or some other such nonsense by a popular culture uncomfortable with the idea of horror movies being good or valuable). I was fascinated by horror from the outside looking in, though, enjoying YouTube series like James Rolfe’s annual Monster Madness series, or feverishly reading the Wikipedia summary for each new Saw movie in morbid fascination. But it wasn’t until I was living on my own that I felt comfortably fully indulging in the breadth of the genre, and one of my main ‘free time’ projects in recent years has been availing myself of all the horror films I didn’t see growing up. One of the best things about becoming a horror fan is that once you find yourself enjoying the genre, you’ll never run out of things to watch, either in the endless backlog, or in theaters (if you like going out to movies, horror is the only genre you can always count on having something in theaters, week in and week out).

All that being said, it still took an inexcusably long time for me to get around to Wes Craven’s titanic classic A Nightmare on Elm Street. I saw it for the first time this August, and the one benefit of waiting so long is that I got to see it in a theater, on the big screen, as part of a series of 1984 films celebrating their 40th anniversaries (1984 was a big year – we already did Prince’s Purple Rain in this Movie of the Week series, and we’ll be discussing a few more from that year in the coming months). Suffice it to say, it was an incredible experience. I found myself vibing intensely on this movie’s wavelength from the word go; even knowing its outsized legacy and loving reputation, I was shocked at just how fresh, fun, and genuinely unsettling the film was. There are some classics that have been so thoroughly digested by popular culture that by the time you, as an individual, finally get around to seeing them, they feel picked clean; A Nightmare on Elm Street is not one of them. It stands firmly outside of time and above its own decades of cultural influence, and it just plays, fulfilling the basic shape of the slasher genre that had already exploded by 1984, but animating it with a singular imagination, soul, and playfulness. It is unusually well-acted, particularly by Robert Englund and Heather Langenkamp, and its scares come from tapping into truly potent evocations of abuse, generational trauma, and the universally understood vulnerability of dream states.

I loved it all so much that by the film’s end, I was genuinely shaking with enthusiasm; when you come out of the absurdly great climax sequence, only to gradually realize we are still (or perhaps always have been) watching a dream, with Nancy going off in the Freddy-colored car and Marge getting pulled back into the house by Freddy’s bladed gloves, only for the film to smash cut to credits with a catchy, celebratory 80s rock song (“Nightmare” by 213), I wanted to stand up and cheer. It’s the kind of mic drop conclusion that feels like Craven is stunting on everyone watching, and by that point, he has more than thoroughly earned it. I was so incredibly jazzed by the whole thing, feeling more like I’d stepped out of a great concert than a movie theater, that there was no way I could have written anything resembling a coherent review that evening; and I know that because my reaction, posted a few minutes later to Letterboxd, was pure incoherent excitement:

FUCK YEAH THIS MOVIE ROCKS SO HARD OH MY GOD.

I LOVE IT.

Actually makes me think way less of Nolan’s INCEPTION because this is a 1000x smarter and more effective use of dreams as a cinematic device, on 1/1000th of the budget. Pure wit and ingenuity. So so so so good. God. Damn.

So yes. I am, officially, a Nightmare on Elm Street fan. I want to sing its praises in a little more depth today, picking up on two ideas I gestured at in that brief Letterboxd freak-out: The comparison to Inception (and other movies about dreams), and the sheer ingenuity of the filmmaking.

On the former, Inception and A Nightmare on Elm Street are obviously different films in different genres aiming for very different effects, and it isn’t an even comparison in either direction. But I think the appeal of dreams in film – a relationship that stretches back to the dawn of cinema, a medium born around the same time Sigmund Freud was founding psychoanalysis, thus cementing a persistent link between them – is that dreams are this bizarre phantasmagoric thing that happen to us when we are immobile and vulnerable, a series of images projected towards us that are wholly unpredictable and, at times, deeply revealing of uncomfortable parts of ourselves. The films that really pull off the ‘feeling’ of a dream – not just the uncanny atmosphere, but also the way dreams challenge and illuminate us in ways the waking world cannot – feel like magic tricks to me, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to the collected works of David Lynch. I am fascinated by movies about dreaming, that use the cinematic medium to recreate this strange yet universal experience we only have a limited scientific understanding of; it’s part of why I eventually fell in love with horror as a genre, because its invocation of the uncanny and willingness to engage with un-reality makes it more capable of tapping into the sensations of dreaming. Heck, the only feature film script I’ve ever written to completion was, in fact, about dreams; it’s a big topic to me.

And that’s why, the older I’ve gotten, the more Nolan’s Inception – which I loved at the time – has felt more and more like a bit of a missed opportunity to me. It’s an extremely fun movie, to be clear, one made with overwhelming craftsmanship, but it treats dreams more like The Matrix treats the titular simulation, or how an isekai anime like Sword Art Online treats a video game world. Nolan’s ‘dreams’ are not liminal spaces of subconscious surprise, but highly controlled, programmatic play-spaces constructed with clockwork precision. A Nightmare on Elm Street is the exact opposite, and the film works as phenomenally well as it does because it understands the core appeal of cinematic dreaming – and, just as crucially, the core horror: that a real dream is something we can never claim ‘mastery’ over, that encroaches upon us in a state of passivity and confronts us with fundamental vulnerabilities. There is something supernatural going on here, of course, with Freddy crawling through these teenagers’ dreams and taking their lives, but that, to me, is a very natural extension of the fear we all live with when we go to sleep at night: that anything can come at us when we’ve lowered the defenses of our own minds, and that, even more terrifyingly, it all comes from within. We cannot escape what we dream about any more than we can escape ourselves.

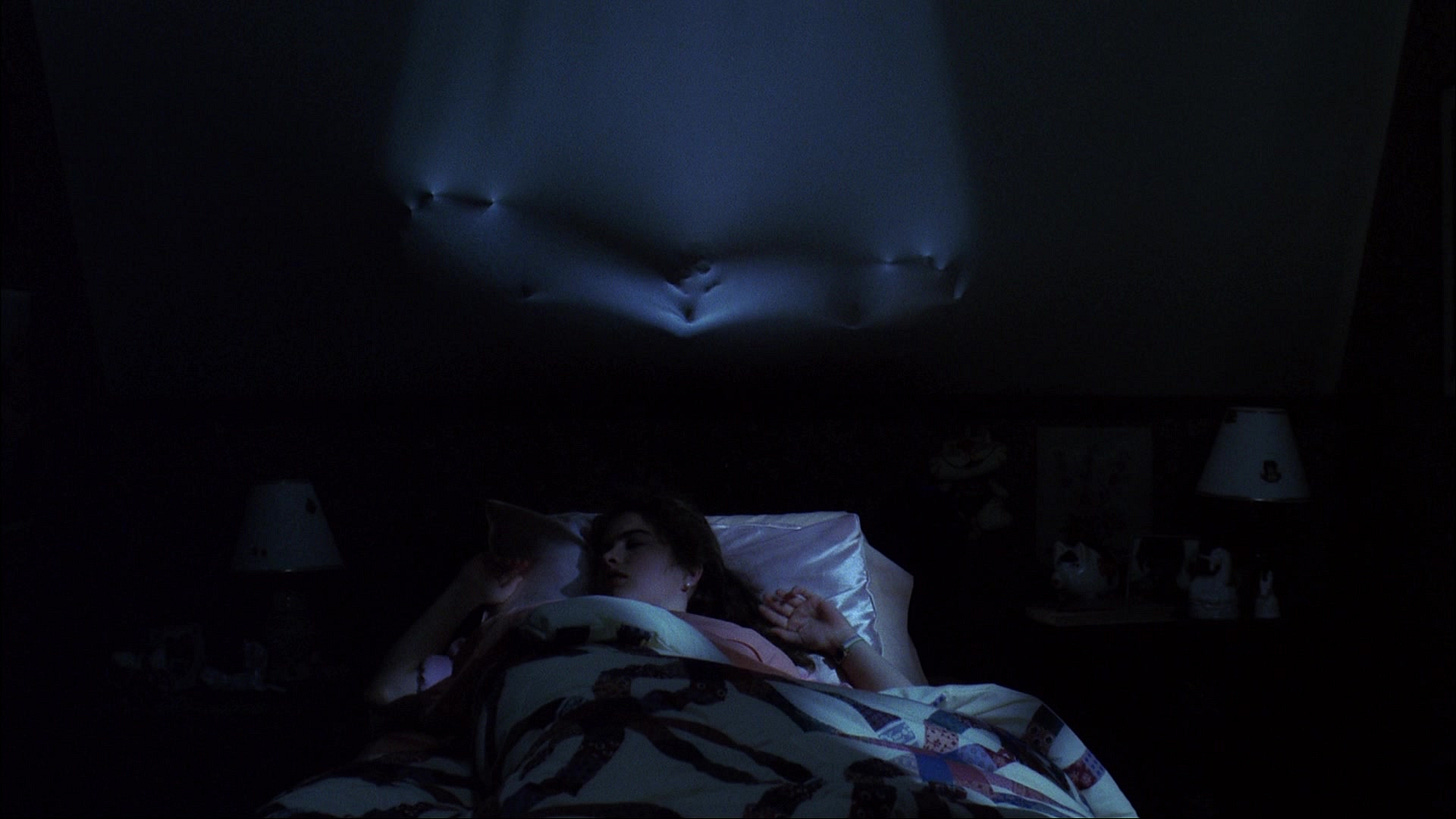

The single most important thing Craven does, to me – and again in total contrast to Inception, which spends most of its first half meticulously explaining how its world works – is that he never lays out the rules, never establishes for us a clear visual or narrative signifier of what constitutes a ‘dream’ versus ‘reality.’ Because dreams, of course, do not have rules, at least not ones we understand; the most common way we come to know we are dreaming is when we wake up, and realize the dream has ended. A Nightmare on Elm Street very rarely signals to us that we’re entering a dream; they simply begin, as part of the overall flow of images, and gradually the uncanny elements add up until we know we’re inside someone’s sleeping mind. There is an instability to the diegesis here, an eerie fluidity to the film language that not only successfully captures the sensations of dreaming, but heightens the horror and Craven’s thematic implications by refusing to draw a clear line in the sand between what is ‘real’ and what is ‘not.’

For instance, through cultural osmosis – by which I primarily mean the Simpsons “Treehouse of Horror” segment with Groundskeeper Willie as Freddy Krueger – I knew the plot of A Nightmare on Elm Street and of Freddy’s backstory, and I just assumed there would be a flashback, at some point in the film, to the parents banding together to burn Freddy alive. But there isn’t; unlike in that aforementioned Simpsons parody, we never see Freddy Kruger in life, and we never get any kind of visual depiction of what happened to him. That entire backstory is exposited through the mouth of Ronee Blakley in an extremely eerie, off-kilter sequence in the Thompson family basement, that is played with the exact same affect as many of the film’s dream sequences. And I’m not at all convinced Craven wants us to take that explanation as gospel; especially considering how much of the film’s final, dream-filled act takes place in that house, in and around that basement space, it can just as easily be read as Nancy’s unconscious mind grasping for rationalizations about this demon haunting her dreams, with an explanation given in the form of her unstable mother (which also gives her a reason to understand her mother’s instability). Whatever the literal ‘reality’ of Freddy within the world of the film’s diegesis, the character is, quite literally, a dream-like symbol, a nightmare amalgamation of fears over child predation. He isn’t ‘real,’ but inherently heightened and symbolic, a shared cultural anxiety given shape by the unconscious mind; nothing about him should be easily decipherable through the lens of ‘reality.’

Part of why the film’s ending works so well is that it offers a seemingly sensible solution to the problem of Freddy – ignore the fear, and the fear goes away – before pulling out the rug and underlining how pat and naïve that way of thinking is; if fears and anxieties could simply be ignored through conscious force of will, there would be no such thing as ‘nightmares.’ Freddy’s essence extending beyond a single body to take the form of a car at the same moment it grabs hold of Marge is the entire film in microcosm: Our deepest, darkest fears grabbing at us when we least expect them. The movie is tough to shake not because we need to fear Freddy Kruger, specifically, will come stab us in our dreams, but because it so vividly illustrates how, when our mind latches on to something that scares or unsettles us, there is nowhere to run, no way out and no escape. Internal fears haunt us more than external threats ever could.

The magic trick of A Nightmare on Elm Street is that by the end, you’re not sure what if anything in the movie happened in any discernible plane of reality, but you also don’t care – It’s all so thrillingly and constructed and disorienting, so good at situating us in a dreamy affect, that the film leaves us both shaken and exhilarated. And that’s where the aforementioned ingenuity of the filmmaking comes in. One of my favorite things about horror movies in general is that, since they’re a genre more accessible to filmmakers with low budgets, they often have to rely on the basic ‘blocking and tackling’ of film craft – shot choice, editing, mise-en-scene, performance, etc. – over visual effects or expensive displays of scale. And Nightmare is an absolute masterclass in working with and around limitations. There are some great gore effects – Freddy’s make-up is particularly remarkable – but most of what we’re looking at is pretty down-to-earth, the dreams taking place in the same mundane spaces as waking life, very little of it looking like special or heightened sets constructed for a movie. That alone adds to the atmosphere – part of why the dreams feel so effectively uncanny is that their settings rarely give them away as dreams – but it also means that most scares have to be produced through the basics of blocking, shooting, and editing, which are consistently exemplary. Even the film’s most memorable and impressive special effect – Freddy reaching out through the wall at a sleeping Nancy – is technically fairly simple: it’s a fake wall built out of spandex, that effects artist Jim Doyle reaches through, as Freddy, with the camera and lighting situated just right to make it look eerily plausible. All the film’s big ‘effects’ are like that, fairly simple magic tricks like a false bottom in a bathtub or red-dyed water pouring down into an inverted set to look like a geyser of blood; even the most elaborate or conceptual images emerge from very mundane locales through smart acts of cinematic problem-solving, and it's exemplary of what can make low-budget horror, at its best, so fiendishly exciting.

Robert Englund gets – and deserves – a lot of praise here, and in the film’s many sequels, as Freddy, and I’m not sure I have much to add to that conversation beyond saying that yes, he’s brilliant, just heightened enough to feel like the product of a sleeping mind, yet grounded enough to be genuinely menacing. But I knew going in that he would be great. It was the young ensemble’s performances that really surprised me, especially Heather Langenkamp as Nancy. She is in every scene, if not damn near every frame, and her subjectivity is the movie’s core point-of-view. She is unusually active in ways horror leads often aren’t (it’s hard for me to immediately think of a lead in a slasher film who moves the plot as aggressively as she does, since slasher heroines are frequently stuck in a reactive posture), and it means the movie’s success really weighs on her shoulders. The film is outstanding in no small part because she is: there’s a real vulnerability and a real strength to the way she plays the character, with those two qualities getting increasingly entangled as she becomes more desperate and reckless the further the film goes. There’s something really immediate and harrowing to her work in the final act, and it helps that both she and a young Johnny Depp read authentically as kids here, not twenty-something adults pretending to still be in high school.

Ronee Blakley is also fantastic as Nancy’s mother Marge, and it’s a performance that strikes me as a sort of relative of what Shelley Duvall does in The Shining. Blakley is playing an alcoholic, where Duvall was playing an abused spouse, but both are inhabiting these women ‘trapped’ in harrowing prisons of American domesticity in such uncomfortably authentic ways that you’ll often see both become targets of criticisms within these otherwise universally praised, classic films. Blakley plays Marge as wounded and coiled, distant such that we understand why Nancy is so independent, but with a palpable sense of humanity beneath it all, and sometimes even humor. That moment at the end, where Marge and Nancy come outside into the sunlight, and Blakeley declares “You know baby, I’m gonna stop drinking. I just don’t feel like it anymore” got a huge laugh out of me; it tells us, just as strongly as the Freddy-colored convertible does, that this is still a dream. The moment and its delivery is very Lynch-ian in its sunny, cheerful absurdity, but also underlines how heavy the material this film is dealing with is, because it so forwardly rejects the ludicrous narrative-ized notion that a battle with Freddy would spontaneously cure this woman’s alcoholism.

After all, A Nightmare on Elm Street is, it must be underlined, an aggressively and wickedly smart film. Craven was an academic before he was a filmmaker – he had a Master’s in Philosophy and Writing from Johns Hopkins, and was a Professor of humanities when he started making short films – and you can feel that background at work throughout this film. It’s obvious in the fierce intelligence underlying the film’s entire understanding and deployment of dreaming; like David Lynch, Craven is a filmmaker who approaches dream-states having done his homework on psychoanalysis and the subsequent decades of clinical and philosophical theory, and who brings more than a passing fascination with eastern spirituality to the table. But you can also sense the academic in Craven in little writerly tics, like the way everyone in this world says ‘Mother’ or ‘Father’ and never ‘mom or dad,’ or how Marge tells Nancy she looks “peaked,” clearly pronounced in two syllables, at the end, instead of ‘sick’ or ‘pale.’ It’s not Quentin Tarantino dialogue where there’s an obvious and intended affect to everything, but just enough of a clear unifying voice – and a voice that’s just a little bit dissonant from how we might expected the characters to sound – that it injects a little extra ‘uncanny’ into the experience, and enhances the illusion that we are in a dream, are in the unconscious sleep-state of a single individual.

It is a misconception by those unfamiliar with the genre that horror movies must necessarily be ‘scary’ to be effective. I think it’s more complicated than that: they can make us laugh, or can disgust us, or offer a really thick, palpable atmosphere, or make us lean forward in our seats with creative, engaging filmmaking. What defines ‘horror’ as a genre, to me, is its root in those kinds of big, embodied reactions, where the film envelops and affects us in some meaningful way, whether that ‘embodiment’ comes from the uncanny, the funny, or, yes, the frightening; and if they can provide some provocative ideas along the way, all the better. The thing that makes A Nightmare on Elm Street a truly great horror movie – one of the great horror movies, a canonical yardstick through which the genre can be defined and judged – is that it does all these things and more. It is the complete package: legitimately scary, and deeply unsettling, in how it uses film language and our understanding of conventional diegesis to question the reality of what we're watching. But it is also incredibly atmospheric, and oftentimes quite funny, and it is a deeply teachable exemplar of film form that is also quite smart and pointed in its provocations. It’s the kind of movie I can easily point to and say “that is why I love horror,” because it does at least a little bit of everything I respond to in the genre. That’s why it endures, 40 years on, above and apart from the series it spawned or the imitators that came in its wake; and if humans are still around to watch horror in another 40 years, I suspect Nightmare will be viewed by them the same way we look at the Universal monster movies of the 20s and 30s, as critical bedrocks of a still-evolving genre.

NEXT WEEK: We look at another horror film celebrating an anniversary, albeit a very different one: Zack Snyder’s 2004 remake of DAWN OF THE DEAD, turning 20 this year.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.