Review: "Anatomy of a Fall" is brilliant, and more than a binary choice

"Did she do it?" is the absolutely wrong question to ask

Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall is a brilliant movie, and undoubtedly one of 2023’s best. It is written, performed, and photographed with astonishing nuance and precision, taking the shape of what could be an intense legal thriller – a man dies falling from his house, with only his wife around when it happens, leading to her being put on trial for his murder – and instead making something slow and simmering, a film about studying faces and sitting with emotions. Set in France but with a German lead character who speaks English with her family – and, notably, never speaks her mother tongue once from start to finish – the film is largely bilingual, jumping between English and French in complex and provocative ways that are worthy of their own analytical essay.

It is, in sum, an outstanding film that demands a whole lot more to fully unpack than I what I am about to write here (or what any one person could write, I think). There is one overarching thought I want to explore, and it will demand speaking in some spoiler-y detail, so if you have not seen the film and do not want to know any more going in, I’ll have another picture below, and after that point, I’ll continue freely with plot details and observations from deeper into the film. For everyone else, I’ll see you on the other side.

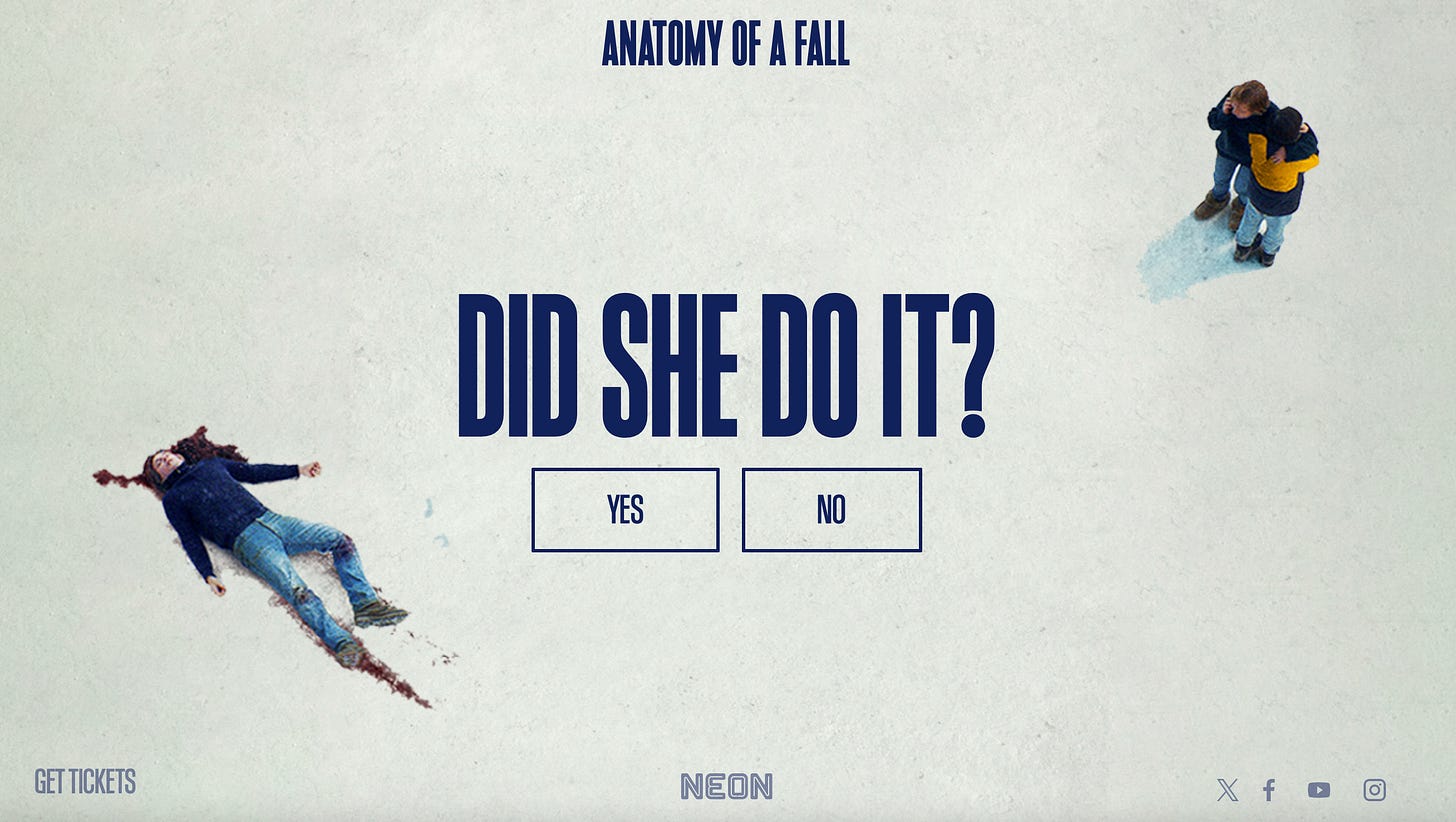

The Neon-distributed release of Anatomy of a Fall playing now in American theaters opens with a card advertising “didshedoit.com.” Going to the link after finishing the film, the page displays a giant binary choice, two buttons for the user to press: YES or NO. Choosing one response then shows the up-to-date results of the poll (currently 34% Yes and 66% No), and gives users space to submit their written reasoning.

This binary “Did she do it?” framing is an absolutely asinine, borderline childish way to frame Triet’s film, and opening the release with this question does a wholesale disservice to the movie that follows. Anatomy of a Fall is about many, many things, but I don’t think it’s ever really, at any point, about whether or not Sandra (Sandra Hüller) actually murdered her husband Samuel. While the film never shows us the incident, I take that much more as an expression of how she and the other characters genuinely do not know what happened to Samuel than as Triet opening the door for audiences to breathlessly speculate about whether or not Sandra did it after the credits roll. The film never presents or frames Sandra as a killer; it presents her and her marriage in the fullness of messy, inarticulate, ambiguous human emotions, and it is just as if not more interested in the shape of the society indicting and questioning this woman as it is in Sandra’s own culpability.

To me, Triet’s film is about two major ideas, represented in the two core characters of Sandra and her 11-year-old son Daniel: First, for Sandra, the film asks how a man can die, and society can put his wife on trial for the crime of being more successful than he was, using that fact as literally the only evidence against her in theorizing his death. Sandra and Samuel are both writers, but Samuel never finished a project, while Sandra continually finished and published successful novels during their marriage; in the opening scene of the film, just before Samuel dies, a woman has come to interview Sandra about her work, and the discussion is interrupted by Samuel playing extremely loud music upstairs, an immature gesture of obvious resentment. The prosecution’s case rests on the idea that it is so unnatural for Sandra to be so much more successful than her husband that she must be in some way deviant, and therefore must be a killer. They contend that she destroyed Samuel’s spirit by being a ‘bad wife,’ by being insufficiently coddling of his fragile male ego, and that this guilt is all that is needed to prove she killed his body as well. That he may have been a bad husband, or they may have been a volatile and imperfect couple, or that there were demons in Samuel’s mind his wife was not responsible for, is impossible for the prosecution to imagine. They are putting Sandra on trial for murder, but what they are really prosecuting is her inability to be a good, quiet, obedient wife. There are countless bits of nuance and ambiguity floating throughout Anatomy of a Fall, but the venom with which the prosecutor tears into Sandra’s perceived imperfections as a wife – which should have no material bearing on whether or not she killed her husband – is not one of them.

(If I have any complaint about the film, in fact, it is the overwhelming and borderline comical weakness of the prosecution’s case. It’s absurdly flimsy, resting only on the vagaries of circumstance and evidentiary material unrelated to the crime, all of which fits the themes of the film, but stresses credulity as a viewer. It is possible this is a cultural difference, of course. In the American judicial system most of what the prosecution presents as evidence would never be admissible, and the prosecutor’s flagrantly combative behavior would be disallowed. I don’t know anything about the French legal system, so it’s possible the film is wholly accurate to a different conception of justice – but from my American vantage point, this doesn’t seem like a case that would ever get prosecuted).

Second, for the son Daniel, the film is about coming to terms with the idea that one of his parents may have been a ‘killer,’ but not the one who is on trial. The only real possibilities are that Sandra killed Samuel, or that Samuel killed himself, the latter being better-supported by the scant evidence and the brunt of what we come to learn about these characters. And of course, that’s also very, very hard for the son to accept. Daniel has to come to terms with the possibility his dad committed suicide, and the film’s final act is largely devoted to following his journey accepting that while he loved his father and his father loved him, that love was not the entirety of who Samuel was – that there were other demons, other dynamics within his dad’s heart and his parents’ relationship, that led to such a dark outcome. And that is aching and brutal and painful, but also very real. There is a profound truth within this film about coming to see one’s parents not as a single loving unit, but a complicated messy intersection between two imperfect individuals; and that truth will be resonant for many of us, I suspect, even if we have not been forced into this revelation by a sudden death and a media circus trial. Daniel’s journey to remembering a key conversation that turns out to be something of a ‘rosetta stone’ for the whole trial is fundamentally the journey of the film – a nearly forgotten memory that turns out to be the most vital piece of evidence, a truth hidden in such plain sight that it could not be seen until acted upon.

This is, as I said, a brilliant film – but it is brilliant not as an ultimately ambiguous Rorschach test asking us whether or not we see Sandra as a killer, the way the idiotic “Did she do it?” framing suggests, but brilliant as a dissection of a marriage and a family unit and all the difficult nuances of human behavior and relationships which create the unstable foundations society wants to project easily digestible cookie-cutter perfection upon. Neon’s stupid website and online poll is only proving Justine Triet’s larger point: The world looks at Sandra and at the case surrounding her and wants to see something neat and binary, a one-word answer to a person and a marriage and a family of real everyday complexity. That is impossible, but the destructive ends of that impulse are very, very real.

If you liked this review, I have 200 more for you – read my new book, 200 Reviews, in Paperback and on Kindle: https://a.co/d/bivNN0e

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our podcast about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all platforms:

https://weeklystuffpodcast.com

I thought she did do it--which is important, give me a break--and that Daniel decided that he couldn't lose both parents. When he is comforting her at the end, it's a little too intimate, almost like the end of Godfather 1 when the family comes to kiss Michael's ring.

hi!the idea of the second picture in your essay is so interesting!may i use it in my film activity in China?looking forward to your replication!