Review: "Battle Royale" turns 25, and is more prescient and powerful than ever

Movie of the Week #33 is one of my all-time favorites

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie, with writing of mine that’s never been published online before.

This week’s choice of BATTLE ROYALE is in honor of the film’s upcoming 25th anniversary screening at CU Boulder’s International Film Series next Wednesday, April 23rd. I will be there in person to introduce the film, so if you’re in or around Boulder, please come see the film with us on the big screen and say hi! As you shall see here, there are few films I hold in higher regard.

Battle Royale

2000, Dir. Kinji Fukasaku

Originally published in the book 200 Reviews, composited from multiple reviews, essays, and original unpublished writing

Kinji Fukasaku’s landmark action-drama Battle Royale finds incredible beauty in one of the darkest premises imaginable: In a dystopian, alternate-history Japan, the tyrannical government demonstrates its control by randomly selecting a class of 42 high school students, aged fifteen, to compete in a battle to the death, where participants must kill one another until only one survives.

Based on Koushun Takami’s 1999 novel, what makes the film adaptation a powerful and profound artistic statement is the highly personal connection Fukasaku had to the material. In his ‘Director’s Statement’ on the film, the filmmaker wrote:

I immediately identified with the 9th graders in the novel, Battle Royale. I was fifteen when World War II came to an end. By then, my class had been drafted and was working in a munitions factory. In July 1945, we were caught up in artillery fire … We survived by diving for cover under our friends. After the attacks, my class had to dispose of the corpses. It was the first time in my life I’d seen so many dead bodies. As I lifted severed arms and legs, I had a fundamental awakening … everything we’d been taught in school about how Japan was fighting the war to win world peace, was a pack of lies. Adults could not be trusted. The emotions I experienced then – an irrational hatred for the unseen forces that drove us into those circumstances, a poisonous hostility towards adults, and a gentle sentimentality for my friends – were a starting point for everything since. This is why, when I hear reports about recent outbreaks of teenage violence and crimes, I cannot easily judge or dismiss them. This is the point of departure for all my films. Lots of people die in my films. They die terrible deaths. But I make them this way because I don’t believe anyone would ever love or trust the films I make, any other way. Battle Royale, my 60th film, returns irrevocably to my own adolescence…

One can see the themes Fukasaku speaks of all over the movie. They are ingrained into each kill, all the flashbacks, and many of the character interactions, particularly anything involving the administrator of the program, Kitano. When one strips away all the graphic violence, explosions, and set pieces, Battle Royale is nothing more than a tale about a group of kids who have been fundamentally let down by the adults in their lives, and must forge independent, resilient identities if they are to survive in such a harsh world. Fukasaku may illustrate these themes in grand strokes, but the film is never anything less than intensely personal, and that is what makes it resonate so strongly.

I first saw Battle Royale right at the age Fukasaku would have wanted: fourteen, just before entering high school. The film was not commercially available in the US back then, but I wanted it desperately. According to ‘the Internet,’ (what seemed like a mystical amalgamation at the time), it was one of the Holy Grails of 21st-century filmmaking, a controversial classic so violent and terrifying it had been ‘banned’ in the US (this wasn’t quite true – movies can’t technically be ‘banned’ in the US because of our first amendment, and Battle Royale simply had never been picked up for distribution by an American company). I had to have it, but it was hard to get, so I started with the English translation of the novel, which had been published by Viz Media in 2003. That only made me want to see the movie more. So I saved up some money and somehow convinced my Mom to help order a bootleg DVD on eBay (in lieu of official distribution, the bootlegs of Battle Royale were actually quite good and easy to find). After a few long weeks of waiting, the disc finally came, and I waited a little longer until my family was out of the house. I eagerly put the disc in the tray, sat down on the couch, and got ready for what I had been assured would be a life-changing experience….

…And you know what? For once, ‘the internet’ was right. After I saw Battle Royale, my existing concepts of the parameters of film were shattered, and I never looked back. My eyes were opened to so many things: how violence can be used not just to thrill, but to educate, to make a point in visceral fashion; that when it takes an active, interpretive mind to find the message in the madness – rather than having it all spoon-fed to you – the results are so much more powerful; that other countries have different styles of acting than America, and contemporary Japanese performances brought emotions to the surface in ways different than I was used to; the role music can play in accentuating themes, feelings, and story points; how much a little tonal creativity and playfulness can amplify the impact of the work; and, of course, that international cinemas can do things and go places that American cinema can’t or won’t. Battle Royale changed everything. I’ve taken it with me on my critical journey through the hundreds of films I’ve reviewed over the years.

First and foremost, Battle Royale is a fully realized artistic statement. That’s not something I would necessarily say about Koushun Takami’s original novel, which says many powerful things without necessarily reaching a singular, unified message. Director Kinji Fukasaku, however, found a very personal connection to the book, and used that to transform the story into his ultimate thesis on one of the animating agitations of his entire life and career: how adults misunderstand and traumatize youth.

This is, of course, the core thematic element of Takami’s novel – youth culture pushed to the brink – and the reason why Fukasaku resonated so strongly with the material. Friendship, love, rivalry, pettiness, and all other fundamentals of teenage society remain, but are heightened, changed, and played with over the course of the battle. An unrequited attraction becomes attempted rape and brutal retribution; past acts of bullying become fuel for murder; the strength of friendship turns into the overwhelming weight of distrust. These inversions are fascinating – and frightening – to behold, perhaps no more so than in the character Mitsuko, a beautiful outsider who becomes an unstoppable force of nature for the very qualities that left her isolated back in school. For all the students, salvation and madness lie only inches apart, demonstrated most powerfully in the terrifying lighthouse sequence, where a simple mistake leads five best friends to kill each other in a matter of minutes.

Battle Royale is a spectacularly violent film, of course, but it’s never exploitative; the gore must be there to illustrate everything I discussed above. As Fukasaku said in his statement, “I make them this way because I don’t believe anyone would ever love or trust the films I make, any other way.” He is absolutely correct. This is a bleak story, and to cushion it by toning down the bloodshed would only reduce its impact. The horror must be absolute for us to truly feel the darkness; only then does the light shine through as powerfully as possible. For even in this shade, there are moments of unsurpassed beauty in Battle Royale, particularly when focusing on the core trio of Shuya, Noriko, and Shogo. The friendship, love, and loyalty these characters develop is as heartwarming as it is heartbreaking – Shuya gives an impassioned speech to Noriko about the need to risk his life that makes me cry every time – precisely because such warmth exists in a world gone so very, very wrong.

Fukasaku’s command of tone, theme, and character is matched only by his authority of pacing and intensity. Battle Royale is a relentless experience, with brilliantly designed, interconnecting fights and set pieces that build in force as the film barrels along at a gripping, non-stop pace. Even if it had no thematic concerns whatsoever, Battle Royale would still be notable as a top-notch action thriller. It is a masterpiece because Fukasaku finds a way to layer character development and subtext on top of the mayhem at every turn.

Yet the film’s most singular and impressive feat is the beautiful performances Fukasaku coaxes out of his vast, young cast. The actors were almost exclusively fifteen or younger, but their work is uniformly flawless, realistic and emotionally palpable from start to finish. These characters feel like real people, not manufactured creations, and that, more than anything else, is what gives the film such tremendous weight. Tatsuya Fujiwara absolutely commands the screen as Shuya (and has gone on to lead a successful career in the years since), Taro Yamamoto gives a brilliant ‘man with no name’ performance as Shogo, Kou Shibasaki’s complex and nuanced portrayal of Mitsuko is utterly captivating, and Chiaki Kuriyama is so breathtaking in her lone scene as Chigusa that Quentin Tarantino cast her as Gogo Yabara in Kill Bill. The rest of the ensemble is not far behind. This is some of the best adolescent acting ever captured on film, especially considering the size of the cast.

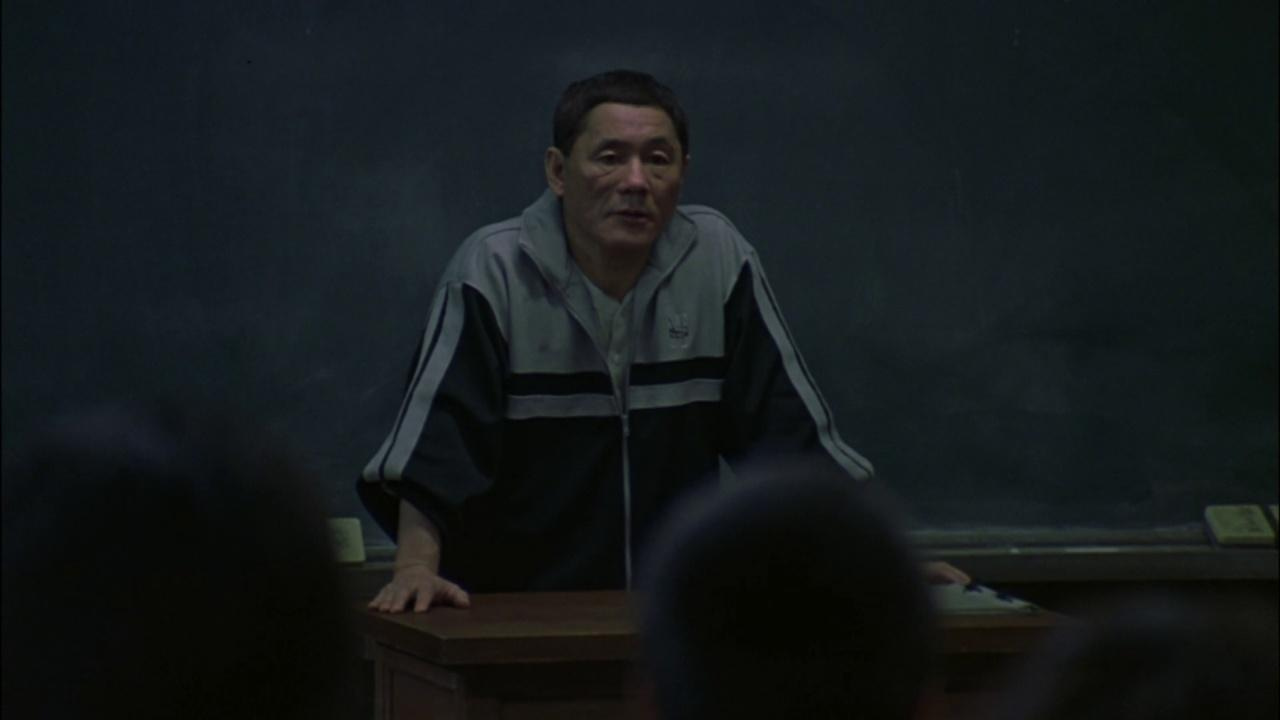

But to my mind, the best character is Kitano, the class’s previous teacher who has returned to administrate the brutal death program. Played flawlessly by legendary Japanese actor/filmmaker ‘Beat’ Takeshi, Kitano is, to my mind, one of the greatest screen presences in movie history. He can be wildly funny and tremendously scary, but no matter what, there is always a profound sadness underlying his actions, and this is the key to interpreting the film. He truly regrets where society has gone, and though he, like the tyrannical government, would like to simply blame the youth, he ultimately realizes it is more complex than that. His class is merely a mirror, and he is a reflection, and once he comprehends the truth of what he sees, he decides this world is one he would rather not live in.

Battle Royale exists in two versions: the original cut released to Japanese theatres in 2000, and a Special Edition extended by eight minutes released one year later. Both are ‘Director’s Cuts,’ in the sense that Fukasaku had complete artistic control over each version, and the extra material added to the Special Edition was actually shot after the film’s release, specifically for the new cut. The Special Edition is the one I saw first (it was the version most widely bootlegged before the film’s first official home video release in the United States in 2012), and I have both nostalgic ties to it and a real love for the scenes it adds, but the Theatrical Cut should not be overlooked. Fukasaku’s original version is a master class in pacing, wasting not one second from start to finish, and delivering a powerfully relentless experience. The Special Edition adds some crucial character details via flashbacks and dream sequences, and while I feel they help flesh out one’s understanding of the ensemble, it sometimes comes at the cost of sacrificing that note-perfect pacing the Theatrical Cut so expertly delivers.

That said, I cannot help but prefer the Special Edition, because it features my favorite moment in the entire film: the concluding dream sequence where Noriko and Kitano walk along a riverside in the city, and Noriko tells Kitano a secret: “The knife that stabbed you, to tell you the truth, I keep it in my desk at home. When I picked it up, I wasn’t sure what to do with it. But now, for some reason, I really treasure it. That’s our secret. Just between us.” Kitano is visibly wounded and confused by this revelation. Not only does this seem to betray the friendship he thought he shared with Noriko, the only student he felt he understood or had any hope for, but it undermines the innocence he thought he saw in her, for she ‘treasures’ something violent. His faith in the idea that the other youth are simply ‘broken,’ and that he can change the world by culling the ‘bad’ ones and protecting the ‘good’ ones, is irrevocably shaken. It leaves him with no choice but to start a dialogue.

“Tell me, Nakagawa,” he says. “In this moment, what should an adult say to a kid?”

The words are repeated in text on screen as the film cuts to credits, and this simple yet profound note is where Fukasaku leaves us, not just in this film, but in the entirety of his long career, as this would be his last film before his death in 2003. The final scene urges adults to begin a meaningful conversation with the youth, to reach across the generation gap, discover what each side holds truly meaningful, and find a way to finally understand one another. These limits that shackle us from each other must be transcended, because otherwise, our fear will lead us to terrors like the Battle Royale, or the wartime conscription that marked Fukasaku as a child.

It is significant that this conclusion is shown as a dream – a dream of no one person in particular, shared by at least two very different characters – because the ensemble nature of Battle Royale means the film is built upon too many individual characters, themes, and ideas for this moment of transcendence to belong to any one person. It creates a new transcendental momentum, one that points towards a place of societal healing, and thus exists outside the confines of the film. This momentum, resolving and supplanting the violence that propelled the film up to now, shall be carried by the audience out into the real world, lingering long after the final frame has projected. I know it did that for me. Battle Royale forever changed how I look at cinema and analyze art, and I continue to carry it with me as I move through the world.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.