Review: Jonathan Glazer's "Under the Skin" is a haunting, unforgettable masterpiece

Few films, if any, have left me as thoroughly shaken as Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin. It is a film that can be reduced to one sentence narratively – Scarlett Johansson plays a mysterious alien in the form of a beautiful woman who prowls the streets of London, seducing and trapping lonely young men, before having an existential crisis and abandoning her mission to further explore her human form – but is so much vaster than any verbal description can suggest, irreducible even to concrete thoughts or interpretations. The film is utterly hypnotic, aesthetically exhilarating and intoxicating to such extreme degrees that time becomes immaterial while watching – at 108 minutes, it feels both eternally long and impossibly short, seeming to last for a mere instant yet with the impact of a cinematic lifetime – and as much as any movie can, it lingers on the brain long after the credits roll, burrowing further and further into one’s psyche the longer one spends away from it. When the film ended, I wanted only to rush back to the box office and buy another ticket, and while that proved impractical at the time, I am positively chomping at the bit to revisit the film at the first opportunity I get. Under the Skin cuts deep and leaves an indelible mark, and while I imagine it will be too formally challenging for most, I believe it is worth a try for anyone interested in what cinema at its most extreme can do to us. The imagery, the ideas, the atmosphere, the deeper implications at play...all of it fascinated me in the moment, and has only rattled around in my head with increasing ferocity in the hours and days since leaving the theatre.

Continue reading after the jump...

There are plenty of stories out there about what it would be like for an alien to enter and experience human culture, but Under the Skin illustrates this notion more thoughtfully and provocatively than any I have ever encountered, in any medium. It’s never about the ‘big’ moments, and there are no grand, climactic displays of misunderstanding or confusion. The film has what is essentially a two-act structure, with the first hour depicting the creature’s mission to abduct lonely men (before we are even sure she is an alien), and that material is so immensely mesmerizing in its quiet, observational reflections. The way Johansson’s character dons a certain ‘face’ when communicating with strangers, versus the cold, analytical gaze she wears in isolation; how she views death as something curious, clinical, and even experimental; how she treats and responds to a true social outcast versus the lonely but socially integrated men she otherwise preys upon; even the way she blinks, in rapid rhythmic flurries, so that we notice, perhaps unconsciously, that this is not a natural action for her. Everything about how she moves through and engages with the world is truly, terrifyingly, captivatingly alien, precisely because the only differences between her and us are so hauntingly subtle and subliminal.

And that’s even before I mention what happens to the men she abducts, something more chilling and disturbing than anything I have ever seen in a horror film, in part because of how resolutely Glazer refuses to give us anything more than a slight wave in the direction of context or answers.

The film’s second act is even more oblique and rich, as Johansson’s character, increasingly fascinated by her own body, goes to the Scottish countryside to further explore the nature of humanity. The film becomes a veritable feast for psychoanalytic theorists, for the alien’s actions are rooted in the awakening of self-image and construction of the ego through the process of seeing and connecting with her own body – in short, a story about ‘mirror stage’ development, through an alien in human form instead of a child. I suspect there are plenty of other ways to read the film, though, especially as the movie grows increasingly open and directionless as it heads towards its powerfully provocative conclusion. The alien’s sudden self-identification throws everything we think we are coming to understand about the film into slow, carefully orchestrated, existential chaos, making it all seem more overwhelming and enthralling in the process. And it lands so hard, with such visceral weight, because her experience is at once both extremely alien and profoundly familiar. We need not reduce the film to psychoanalytic terms to understand how universal the process of reconciling our internal and external selves is to the simple act of existence.

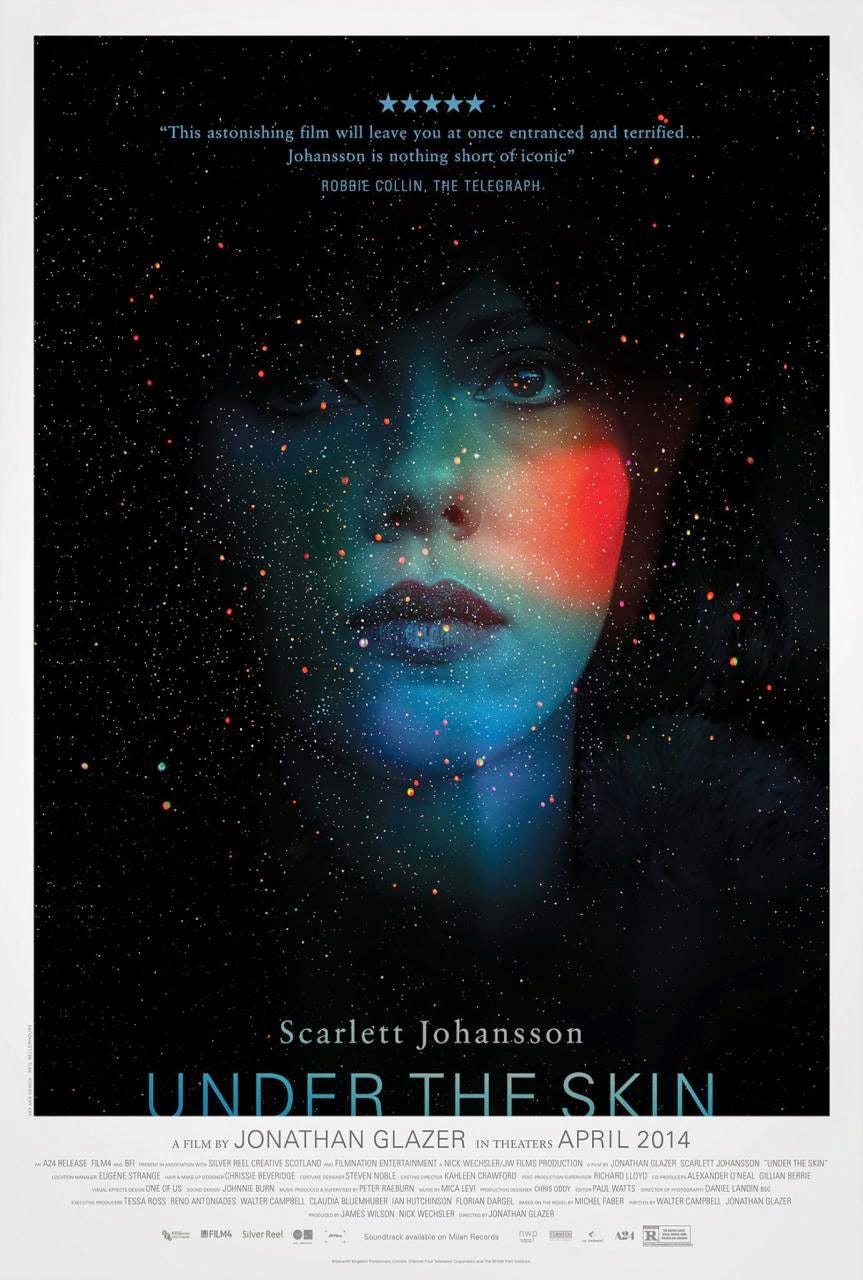

The aesthetics are everything to Under the Skin, every part of what makes it such an infectious, all-consuming experience. I was amazed to learn, watching the credits, that the film is in fact based on a novel by Michael Faber (loosely, as I understand it), because nothing about the movie strikes me as literary in the slightest. This is pure, intensely sensory cinema, the kind of film that cannot be described by its narrative, but only by the ways in which its small number of incidents are aesthetically invoked. Every shot, even seemingly simple ones of Johansson searching the streets in her van, are deeply thoughtful and visually stimulating, but the ‘big’ visual moments – of which there are many, most of them immensely surrealistic or formally daring – are the kinds of cinematic images I imagine will be forever burned into my retinas, unforgettable and deeply piercing. I might even consider the film legitimately avant-garde, because while its form is not necessarily experimental, it is absolutely aesthetically radical, on every level. The sound design, for instance, is positively haunting, often a complete din, with dialogue mixed roughly and even unintelligibly; the thick Scottish accents were essentially indecipherable to me, but I think they might be even to Scottish people thanks to the mix, which seems to intentionally compound the alien-ness of it all. Mica Levi’s musical score is an ambient masterwork, overpowering one’s ears with sinuous, strained strings, like an Orchestra from hell, playing over the most intense visual moments in ways that seem to literally crawl under the viewer’s skin. Combined with the perfectly paced, extremely deliberate editing, a general sense of atmosphere so complete and disorienting is created that all external considerations – time, the physical world, the theatre itself – seem to just slip away, the viewer utterly hypnotized under Glazer’s spell.

Scarlett Johansson is the only major actor or character in the film (most of the men she encounters were played by non-actors), and her work here is just brilliant. I don’t know if one can fully comprehend the degree of inspiration her work represents until one gets to the film’s end and sees the full scope of what her character is, but once one does, it becomes clear that there are many layers at play in her performance. Her work is all about projecting quiet, sublimated existential confusion, with each successive moment building off the last in a characterization that has true, devastating cumulative power. It’s a total performance built around physicality, meaning that she’s relying on so much more than facial expressions or dialogue (of which there is very little), but also the way she holds herself, and the way she moves, and the way she uses her hands and fingers, and the way she interacts with clothing or cars or other objects. Johansson seems to become a better and more compelling actress every time I see her, and Under the Skin is a true revelation. Between this and Captain America: The Winter Soldier, it’s clear she’s just as adept at big, movie-star performances as she is serving as the lynchpin for a potentially avant-garde work like this, and that’s something very few actors are capable of.

It’s taken me three days to wrestle my thoughts on this film into review form, to parse through my thoughts and reconsider every image and idea the film left me with, and I know Under the Skin won’t leave me alone after publishing. This is a film I cannot wait to see again, and one I know I will be writing about in a lot more depth in the weeks and months to come. It is a masterpiece, plain and simple, a bold and beautiful work that will have a permanent place in the annals of film discussion, and while I would, again, caution readers against experiencing the film unless they are clear about what they are in for – I do not toss around the term ‘avant-garde’ lightly – I obviously cannot recommend it enough as a powerful, profound, and truly unforgettable cinematic wonder.

Under the Skin is now playing in Denver at the Landmark Mayan.