Review: “Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack” and the Allure of the Asteroid

Movie of the Week #15 is doing something extremely wicked

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a weekly column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week. This column is usually for paid subscribers, but since there were 5 weeks in October, this one is free for everyone. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

Part 1: Char 360

To quote Charli XCX: “I think about it all the time.”

Only by ‘it,’ I don’t mean the pressures of balancing prospective parenthood with a successful pop career; I instead mean the asteroid, Axis Zeon, from the seminal 1988 anime classic Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack.

I really do think about it all the time: The plan devised by roguish anti-hero Char Aznable to crash a massive asteroid into Earth’s surface, destroying the existing population and power structures, forcing humanity to become a spacefaring ‘Newtype’ civilization, and creating the conditions for Earth to renew itself on a long-term ecological scale, free of mankind’s pestilential influence.

Char (aka The Red Comet, aka Casval Rem Deikun, aka Quattro Bajeena, aka Edouard Mass) is not only the breakout character of Mobile Suit Gundam’s first decade, but arguably its central figure. Introduced as a swashbuckling antagonist with a shit-eating grin, he turns out to be something of a tragic, Hamlet-esque protagonist by the end of the original series, before returning as a conflicted hero and reluctant leader in the sequel series Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam. Leadership and heroism don’t rest easy on his shoulders, and he ends Zeta Gundam defeated in more ways than one. Here, in Char’s Counterattack, he returns with an apocalyptic zeal, shocking in both its devastating ambition and in how darkly seductive it is to the audience. Our ‘true’ hero, Amuro Ray, the original boy in the eponymous Gundam, is here too, and he valiantly resists Char’s efforts. We want him to succeed, want to see him stop Char and save the Earth…but not as fulsomely as we might expect. After having followed both men, and thoroughly explored the world around them, through three full TV series, we arrive here at the climax unable to fully support the protagonist or wholly damn the antagonist. This world is, indeed, broken: we have seen its holistic lack of leadership, its tendency towards unspeakable violence, its penchant for turning children into soldiers. The central philosophical gesture of the Gundam mythos, the ‘Newtype’ – a utopian expansion of human consciousness – has been weaponized time and again towards increasingly appalling ends. We cannot abandon Amuro or root against his success, because to do so would be to damn ourselves as human beings; and yet, neither can we look at Char and definitively declare that his literally scorched-earth solution is wrong.

Maybe you see where I’m going with this. Why, since I fell head over heels for all things Gundam in 2019, I have never been able to stop thinking about the dilemma of Char’s Counterattack. Why our world, through these last five years, has made it so hard to get this movie out of my head. I think about it all the time.

The question writer/director Yoshiyuki Tomino poses in this film, and the starkness with which he poses it, makes Char’s Counterattack both endlessly rewatchable and infinitely permutable. The film is a virtuosic symphony of sound and fury, raged over a philosophical question that seems to define the times in which we live: Is the broken, unjust civilization we find ourselves saddled with worth working to improve, or would it be better to just drop the asteroid, wipe everything back to zero, and let Earth try again, with or without us, in another epoch or two? Char and Amuro both have their answers, and the brilliance of Char’s Counterattack is that each of them is wrong. They both die, and in their collision and mutual self-destruction, something greater, more profound, and more unknowable is born: a vision of a force transcending the binary of ‘hope’ and ‘hopelessness’ in which we find ourselves perpetually mired.

The story of Tomino’s career is one of these divergent impulses warring for supremacy within his work. The man who would let it all burn made 1993’s Mobile Suit Victory Gundam, living up to his ‘Kill ‘em All Tomino’ moniker (and then some) with a series that paints a bleak portrait of a civilization deep in the throes of entropic collapse, where ‘victory’ is, at best, a stay of execution. It is suffocatingly dark, and profoundly affecting. That despair gives way, ultimately, to thinking on a vast cosmic timetable, as seen in 1999’s Turn A Gundam. Here, he envisions a world that has rebooted from zero, as Char Aznable once envisioned. In some ways, it is a better and more hopeful world, a vindication of that instinct to let the broken burn and give the future a chance to flourish. In other ways, it is a rejection of Char’s logic, as Tomino here acknowledges that some problems are cyclical and immutable, and therefore intransigent, embedded in the human condition and not the specific permutations of our societies and structures. In his most recent work, 2014’s Reconguista in G, Tomino leaves it to the youth with an old man’s message: that if one travels enough, and experiences enough, and learns enough, maybe a better world can be built on the backs of the fools who came before – and brick by brick, generation by generation, we will continue building on. Neither Amuro Ray nor Char Aznable lived to be old men, of course; they were never party to that kind of wisdom.

In this way, Char’s Counterattack is, in some sense, the apex of Tomino’s career, and a load-bearing pillar of the entire Gundam project itself. With masterful, immersive kineticism, it lays out these two young man’s impulses that war inside anyone old enough to see that we’re fucked, but not old enough to have come to peace with our individual inability to un-fuck things. It captures, in haunting and visceral fashion, that horrible push-and-pull between maintaining faith that humanity can, in Amuro’s words, “learn and grow,” and feeling, as Char expresses, that mankind must “atone for their sins against nature and Earth.” Do we stay the course, or do we invite the asteroid? What could we have done differently to never reach this fork in the road? Is there another path to take, one we as individuals cannot comprehend?

Char’s Counterattack is constructed on incredibly potent moments and images that uncannily encapsulate the evils of our times. Take, for instance, Char buying the tool to destroy the Earth with literal briefcases full of gold. He meets in secret with a bunch of Earth’s politicians in a lavish board room, and bribes them all into giving him the power to manifest Armageddon. Apply this image to any scenario where politicians take cold hard cash in exchange for letting bad actors kill their constituents, like the fossil fuel industry buying themselves leeway to supercharge global warming, or the NRA and gun lobby buying increasingly permissive gun laws to create more mass shootings to fuel more gun sales, or polluters supporting politicians who, through their laws and judicial appointments, grant access to poison our water and air. It is almost too on the nose, which is to say, it is uncomfortably honest. I am writing this piece days after Jeff Bezos, the second-richest man on Earth, unilaterally scuttled The Washington Post’s endorsement of Kamala Harris, mere hours before his company Blue Origin met to negotiate with Donald Trump. Like Adenauer Paraya and the corrupt, feckless ministers of Earth, Bezos saw the asteroid coming, and instead of leveraging his power to try stopping it, he engaged in anticipatory obedience, getting his while the getting was still good.

At least Char Aznable has the wherewithal to know he is doing evil. No self-serving editorials whitewashing the villainy for him. “Amuro,” he says, looking out the window through the sunglasses he uses to shield his inner life from the world. “I’m doing something extremely wicked.”

At least Char Aznable believes his wickedness will create greater good in the long run. Given how easy it was for him to procure the world-destroying asteroid from the government tasked with protecting that world, it’s hard to say he’s completely off base.

Nor can we easily dismiss Char’s frustration with Amuro, the most gifted Newtype this world has yet seen, who is still ‘just’ a pilot, taking orders and fighting to defend the system that would sell its own apocalypse. Amuro is a better soldier, a truer Newtype, and a more emotionally stable person than Char could ever be, and Char knows it all too well; he still bears the scar from their last meeting in Gundam ’79, right in that same ‘third eye’ spot on his forehead where Amuro’s ‘Newtype flashes’ originate. Char detests that, between the two of them, it is he who is out there trying to change the world; that should be Amuro’s job, and it should be left to Char to go fly around in his slick red mobile suits, serving himself on the battlefield where he was always most comfortable. Neither man’s gifts are being optimally employed.

But extremism has a way of rendering cautious even those who could be great heroes. Amuro steadfastly stops the world from becoming emphatically worse, and there is real heroism in that, real lives saved and real atrocities averted; but there would likely be a much greater heroism in Amuro answering Char’s radical solution with a politics of his own, a movement that neither accepts the wholesale destruction of the system nor its continued, untenable stagnation. Amuro Ray is not a coward; we understand how he came to be this way, if we have watched the series up until now, and seen the ways he was thrust into the center of things because every other adult failed him. And yet, there is a tragedy in his story, in the arc of a boy who became bold and heroic in some ways, even as he remained small and insular in others.

I cannot help but see part of America’s tragedy reflected in Amuro, where the accelerating fascism of the Right has not made the defenders of democracy bold enough to full-throatedly counteract their evil. We too are trying to prevent the world from becoming emphatically worse, even as we fail to present the countervailing vision necessary to stem the tide of extremism. I do not look at Kamala Harris’ altogether competent – but something less than rousing – campaign and feel bafflement over how we got here, how we ceded so much ground on immigration or democratic reform; I lived through these last nine years and understand the context. But there is still a tragedy in that. The most important election in our lifetimes wasn’t 2024 – the moment we decide whether to invite the asteroid or repel it – but 2016, when we set ourselves on this path; I am not now and was not then a ‘Bernie Bro’ (not because I disagree with his politics, but because I detest cults of personality), but history will always wonder if Sanders or a candidate like him – someone who did have an alternative view of radical change, rooted in building rather than destroying – could have stamped Trump out at that first pass, and steered America down a different path of reform. Just as one wonders, watching Char’s Counterattack, if any of this would be happening if there had been someone else to stand up in Amuro’s place in the One-Year War and its aftermath. Would we need the Axis Flash in a world where Amuro Ray never had to get in that Gundam?

Maybe this reading of contemporary American politics through the lens of a 1980s Japanese cartoon about giant fighting robots strikes you as silly. But the purpose of fiction is to present ideas in the shapes of stories that help us give shape to the world around us; we go to fiction not just for entertainment or escape, but to try understanding through narrative what is incomprehensible in formless mess of everyday life. And the narrative shape of Char’s Counterattack is nothing less than a perfect prism, capturing and refracting the light we shine upon it, taking on new visages every time one comes back to it.

I sometimes hear from fellow Gundam fans the sentiment that Char’s Counterattack ‘should’ have been a TV series or multi-part OVA, to give the story and characters more room to breathe. I vehemently disagree. Put aside for a moment the fact that extreme narrative compression is a hallmark of Yoshiyuki Tomino’s style, and that a longer version of Char’s Counterattack wouldn’t necessary be a slower version; it simply isn’t the way he works. What’s more important is that there is, inherently, a focusing effect at work when one produces a story as a movie, as a bounded two-hour experience that begins and ends with the intention of being viewed in one sitting. The ‘shape’ of Char’s Counterattack matters, and that shape is inherently cinematic. It is a concentrated two-hour journey we get swept up and lost in, that begins more or less mid-stream and ends on something of an ellipsis, with the tension ratcheted up exponentially in between. There is a sprawl to the film in the size of its cast and the amount of on-screen action and mayhem, but there is also a crystal-clear spine undergirding and focusing it all. The power of the asteroid as metaphor works because it is articulated in the shape of a movie, where that central question – To Armageddon or Not To Armageddon – is the gravitational center around which every plot point and character interaction orbits. A TV or OVA version of Char’s Counterattack would necessarily require additional spines and other digressions; often these things can be vital and wonderful, as Tomino’s extensive TV work attests. But Char’s Counterattack works because of the intensely focused punch it delivers, and that punch is inherently cinematic in structure and in scale.

I certainly did not appreciate all this on first viewing. It is not uncommon, I think, to watch Char’s Counterattack once and find it a little awkwardly paced, or to be taken aback by the abruptness of the ending. But then it worms its way into your brain; you think about it all the time, as it begins to affect the way one sees the world, starts coalescing into a prism through which one understands things. And eventually you watch the film again, and again, and, if you’re me, a few more times for good measure, and you realize this invasion of your subconscious is no accident.

The movie is the way it is because it is actively capturing the essence of ‘conflict.’ It is cinematically dialectic – a collision of thesis and antithesis – in a way Sergei Eisenstein might not immediately recognize (Char’s Counterattack is not propagandistic) but would surely appreciate, because it is built to agitate. The way the film lacks a conventional beginning or ending, starting mid-action and concluding mid-action, is part of this; every scene in between is also suspended between similar poles of ongoing chains of causality. Everyone is always moving and always reacting. It is hard to catch a breath. I encountered the film first in 2019, right before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and while today I can eloquently tell you how the film helps me understand my own push-and-pull between nihilism and hope the period that followed instilled in all of us, my reaction at the time was more primal. There is something about the form of Char’s Counterattack, about the symphonic chaos of Tomino’s direction, that resonated so powerfully with the lived experience of those years. In compressing what would in anyone else’s hands be a movie two or three times as long into two hours, Tomino’s work captures that feeling of permanently reacting, and fighting, and fleeing, and trying to incorporate new information, without ever finding a firm resolution. The film is suspended on the eternal knife’s edge of conflict, of thesis and antithesis, of hope and despair, of attack and counterattack. The ‘ending,’ such as it is, isn’t so much a conclusion or denouement as it is a visualization of dialectic collision: not resolution, but release, and in that release, creation.

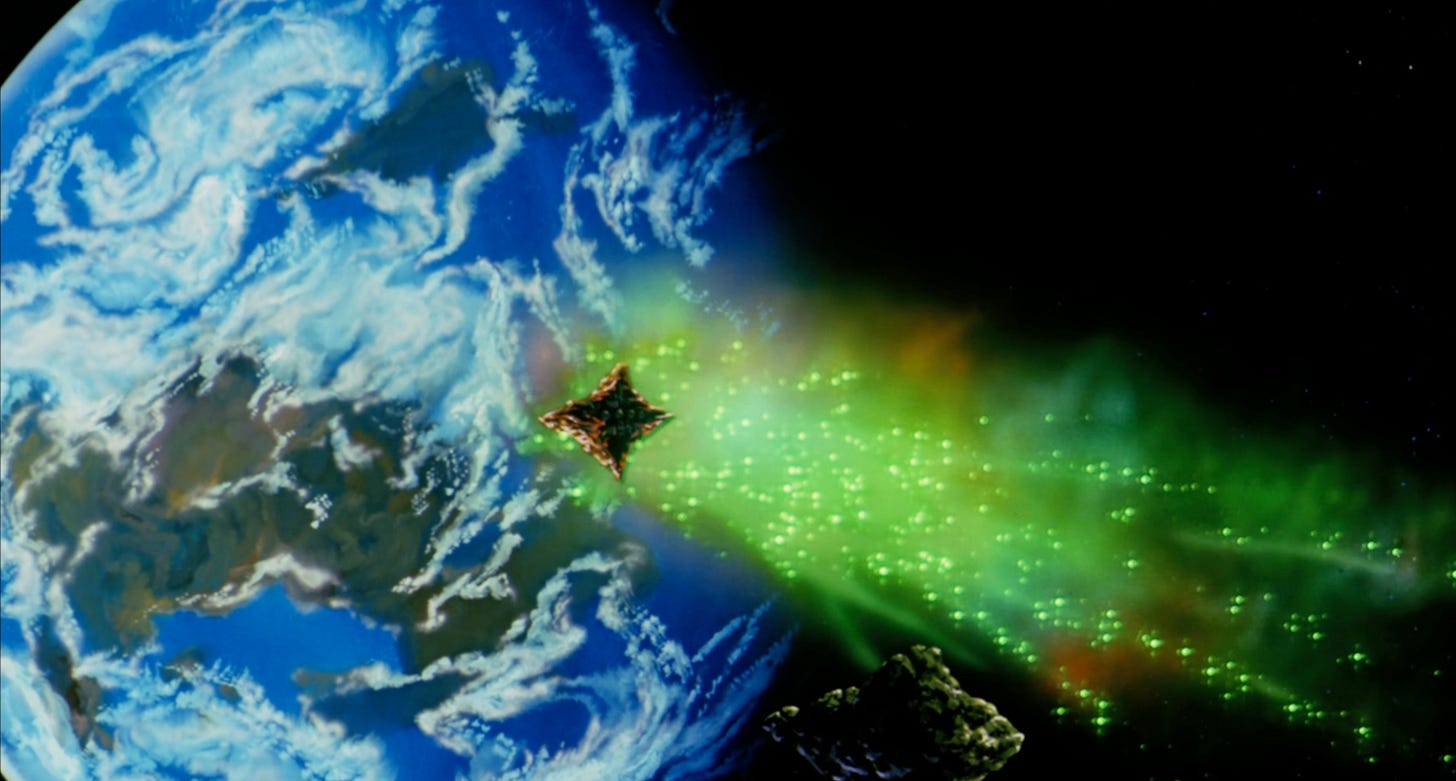

This is, of course, how life works: We live for the most part amid change and collision, and ‘endings’ are largely phantasmagoric. There is only one true ‘resolution’ for human beings, and none of us will be conscious of it when it comes. Amuro and Char aren’t aware of their ending when it arrives either, of course: they are literally consumed by larger forces, shapeless and unknowable, that exist beyond the confines of individual comprehension. This force takes the form of that eerie green light, channeled through the T-shaped psychoframe, engulfing their mobile suits and, eventually, the planet. It is the light of the will to live.

The enormity of the ‘Axis Flash’ climax seems to come suddenly, but the mechanics of it all do make sense, if one follows the path of the psychoframe across the movie. No one is going to get all that on a first viewing, though, and that is by design. No individual character comprehends it either; that little device passes through so many hands, lead to Char and Amuro at the moment their conflict reaches its unresolvable climax by so many permutations of individual choices and reactions to those choices and reactions to those reactions (including its role in the tragic Hathaway/Quess/Chan episode). The path it traces operates at the register of society and fate, vaster forces than any one person can control. No one will ever understand the Axis Flash, really, except to conclude it represents the will of enough living people to go on living – to assert that neither Amuro’s answer or Char’s answer is enough to cure what ails us – that we survive to struggle with these questions another day.

I don’t think Tomino himself could quite have explained the potency of what he came up with in 1988. It is a purely visual and emotive expression of the idea he would hone with greater intentionality in Turn A Gundam and Reconguista in G: that there is a collective will we all play a part in, and the sooner we suppress our ego enough to become aware of that, the sooner we can go about un-fucking things, never in their totality, but in small ways best we can, brick by brick, day by day.

As much as Char’s Counterattack is fundamentally dialectical, I do think its sympathies, and its admiration, ultimately lie with Amuro. Yes, there are surely ways he could have used his Newtype powers and experience to help steer the world towards a place where Char would never have gotten this far; as the better man, maybe he even could have helped redeem Char, if he had the wherewithal to try. But Amuro is, at least, willing to risk it all to stop the asteroid, to actualize the faith he has in mankind in a desperate attempt to repel Armageddon with a single mobile suit. And, it turns out, enough other people are willing to do that too, are willing to push against the seemingly unstoppable mass of solid falling rock – to fight back against the immutable fact of gravity that weighs down their individual souls – that something sparks, and the power of mass consciousness – the heart of the Newtype theory Zeon Zum Deikun once put forth – is unleashed to momentarily reverse gravity and entropy.

That’s how it always happens though, isn’t it? That’s what hope is. That’s what we have to trust in, every time we are audacious enough to think we can make the world better: That enough of us won’t give into the allure of the asteroid, won’t accept the gravity that weighs us down, that together we will be granted the opportunity to try again tomorrow. That’s the rub in this whole dilemma, ultimately: If one accepts the asteroid, one also embraces a state of powerlessness, stakes our existence on a sense that the world is well and truly lost and cannot ever be repaired. Merely pushing the asteroid back is not enough; of course it isn’t enough. But if it is not repelled, nothing else can be done. Human consciousness must rebel against the asteroid, if it is to persist, because the logic of the asteroid is inherently inhuman. Even if human beings are bad; even if the Earth would be better off without us; even if rejecting that logic is selfish in the grander scheme of ecology and the cosmos. It is, in the end, the only way we can live.

Part 2: Char 365

My brother has watched a good chunk of Gundam, at my urging – it’s hard to know me and not become acquainted with the series to at least some degree – but while I think he understands why I love it, and I think he could tell you all the reasons Char Aznable is such a dynamic and iconic character – the design, Shuichi Ikeda’s performance, all those awesome red mobile suits, etc. – he’s never quite understood the degree of my obsession with the character. When the original Mobile Suit Gundam film trilogy played in American theaters for the first time this last month, he accompanied me to the first film, and raised an eyebrow when I cheered at Char’s first appearance. It’s not an illogical response, I suppose: Char is introduced to us as a villain who tries, over and over again, to kill a ship full of children, whose brief flirtation with actual heroism in Zeta Gundam is admittedly cancelled out rather severely by his aspirations towards mass murder on a scale hitherto undreamt of in human history in Char’s Counterattack. Char Aznable is, by any conventional or reasonable definition – and by his role in the story through most of his time in Gundam – a bad guy.

And yet. I love Char Aznable. If I have a Mount Rushmore of fictional characters, he’s on it, right up there next to Son Gokū or Bilbo Baggins or whichever other morally and spiritually ‘pure’ figures might appear there. And I don’t just love Char because he’s the coolest-looking motherfucker in the history of anime; or because Shuichi Ikeda consistently gives one of the all-time great performances – vocal or otherwise – in the history of moving image media; or because all of Char’s mobile suits are all cool as shit and painted striking shades of red (and the one that isn’t is literally solid gold). It’s not even just because Char Aznable is positively Shakespearean in his complexity, Hamlet if his vengeful ideations took the form of years-long subterfuge and half a dozen identity shifts; he is, truly, one of the most dynamic and compelling characters of the 20th century, in any medium.

No, even putting all that together doesn’t quite describe it. I love Char Aznable because he is, to use a crude turn of phrase, a messy bitch. The world’s coolest cucumber on the outside, a roiling sea of grief and anger and insecurity on the inside. A person with real ideals and beliefs and a sense, however warped, of honor and loyalty, who often sacrifices all of that on the altar of selfishness, pride, and ego. He is an Important Person living in a time of maximal historical impact, and he finds himself buffeted by the winds of the times as much as he moves them himself. He is talented, charming, beautiful, and gifted: everything a hero should be. And yet he continually finds that the only way to make sense of the world is to be its villain.

Char Aznable is small, in a way men who do great evil usually are. Behind his bluster, regalia, and commanding voice, his singular elocution declaring a desire to renew mankind in space, he is ultimately self-serving. I think Char is sincere in his assessment of the world and its politics, and that he truly believes his plan to crash the asteroid and force a migration off earth is for the greater good; I also think that if that plan didn’t give him an opportunity to get in a big red mobile suit, play soldier, and fight Amuro Ray again, he never would have gone through with it. So much of Char’s Counterattack is devoted to watching characters talk about Char Aznable, trying to figure him out; even Char himself engages in this. But the ultimate truth of Char is actually disarmingly simple. His final words – “Lalah Sune was a woman who may have become a mother to me” – are the Rosetta Stone to unlocking his deepest interiority: A boy who lost his family, grew up filled with anger and sadness, never learned to emotionally regulate, and found himself most at home in the cockpit of a mobile suit, buried beneath masks and uniforms, imposing on the world the same chaos he feels in his heart. Amuro is flummoxed when he hears these words from his rival; Char always seemed so big. But Char Aznable is, ultimately, so small – as are most of us, by simple virtue of being human.

Yet in his smallness, Char is also towering, because in that complex, petty, messy mixture that forms his personality and actions, he feels in some ways like a note-perfect portrait of what it feels like to live in the world today. I watch Char Aznable and I root for him to be his best self, even as I simultaneously understand why he so rarely is. In some sense, Char is all of us: Our best and our worst, warring for internal supremacy, capable of seeing mankind’s evils with clear eyes, yet ultimately self-destructing in attempting to make sense of it. Char Aznable is the fictional character I have spent the most time thinking about these last five years, and that will very probably be true for the next five. Because one way or another, as we live every day watching our systems and societies and faith in each other curdle and erode, we are all reflected and refracted in the shape of Char Aznable.

What I guess I’m really trying to say here is this: Char is Brat.

She’s just that girl who is a little messy, and likes to party, and maybe says some dumb things sometimes. Who feels herself but maybe also has a breakdown. But she parties through it, is very honest, very blunt. A little bit volatile. Like, does dumb things. But it’s brat. You’re brat. That’s brat.

NEXT WEEK: We kick of November with another anime adventure, and this time it’s a triple feature with Takeshi Koike’s LUPIN THE IIIRD trilogy, consisting of Jigen’s Gravestone, Goemon’s Blood Spray, and Fujiko’s Lie. Take a look at everything else coming to MOVIE OF THE WEEK this month!

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Beautiful