Review: "The Peanuts Movie" gives me newfound hope for Humanity and Hollywood alike

The Peanuts Movie is such an anomaly for Hollywood animated family films, in so many ways, that the more I think about it, the more pleasantly flabbergasted I am that it ever got produced. Here is a major family tentpole, in the year 2015, that lacks even a single pop-culture reference or scatological joke, with nary a celebrity voice in sight, and which eschews any semblance of a high-concept narrative in favor of an exceedingly gentle story about disappointment and optimism. It does not look like any mainstream CGI movie ever made, with a delightfully stylized visual approach that boldly refuses to conform, and it is not winking, cynical, coy, or anything other than whole-heartedly earnest about the world of Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts. Seeing Hollywood be this reverent of source material this old and beloved is one thing; seeing it be this reverent of Peanuts, a franchise that is so manifestly opposed to nearly all that defines modern family filmmaking, is sort of startling.

Continue reading after the jump...

In fact, even by the standards of Schulz’s comic strip and original TV specials and films, The Peanuts Movie is amazingly low-key. The entire plot centers around whether or not Charlie Brown will muster the courage to strike up a friendship with his crush, the ‘little red-haired girl,’ and while there are sequences of heightened slapstick or imagined adventures, the narrative never becomes anything more complicated than that basic interplay between Charlie Brown and his insecurities. In the grand canon of Peanuts, even Schulz himself could not always be that focused and down-to-earth; I remember Charlie Brown engaged in a summer camp river rafting race, or travelling to spots around the world, in addition to the more iconic (and subdued) stories about finding the perfect Christmas tree or waiting up all night for the Great Pumpkin. This new film could have gone in one of those more high-concept directions and still be true to Peanuts; it could also just as easily have thrown all that out the window and crafted an elaborate origin story, about Charlie Brown meeting Snoopy for the first time, or made the film completely Snoopy-centric and dismissed anything not related to slapstick. They could have cast Justin Timberlake as Charlie Brown and have him start a rock band, or had Charlie Brown and his friends discover a mystical burial ground underneath their school. None of it would have been even remotely out of the question for the way Hollywood tends to treat beloved children’s franchises of yore, and I am certain I cannot be the only one worried, when The Peanuts Movie was announced, that it might have Schulz spinning in his grave the way Dr. Seuss is continually made to do in his.

But instead, director Steve Martino and the team at Blue Sky Studios have decided to build their film around the very essence of the Charlie Brown character: a boy who is not gifted with special powers, does not learn the world literally revolves around him, and does not find himself tasked with saving the day, but is instead confronted with the everyday challenges and disappointments of being a child, and whose heroism comes from always getting back up when the literal or metaphorical football gets pulled out from under him. And the thing I love most about The Peanuts Movie is that, by the end, Martino and company have made that core character trait feel more significant and aspirational than any high-concept narrative ever could. Their love and enthusiasm for the simple pleasures that have always allowed Schulz’s world to endure shine through loud and clear from first frame to last; they sincerely believe in these characters and their world, and above all else, that passion is what elevates this from a simple nostalgia trip to a genuinely touching and impressive achievement of modern animation.

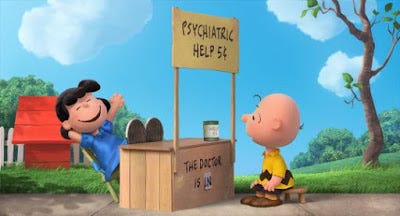

Nostalgia is a part of the equation, of course. Martino and company quote many Peanuts ‘greatest hits’ moments, and for any adult who has been exposed to the original comic-strip and cartoons from a young age, a lot of this is going to feel familiar. Linus still loves his blanket; Lucy still charges five cents for amateur therapy; Charlie Brown still says “Good grief,” still has trouble flying a kite, and is still perpetually unable to kick that football; and Marcie and Peppermint Pattie are still engaged in something resembling a one-sided and mildly manipulative romance. But if this is not the first time I have seen these tropes play out, it will be the first time, I imagine, for the vast majority of the young audience The Peanuts Movie is primarily targeting. And it warms my heart to know that, in 2015, with technology and culture having seemingly eclipsed the franchise’s relevance to young people, these characters can still feel just as sharp, amusing, and original to a child today as they did when I was growing up. I saw this film on a Sunday morning, in its second week of release, and the auditorium was packed with children who could not get enough of it. If that isn’t movie magic, then I don’t know what is.

And the level of execution is so high across the board here that I doubt any fan, no matter their age, will come away feeling like they’ve been served reheated leftovers. The first thing that struck me is just how funny this film is. I saw it at the Alamo Drafthouse, and one of the traditions there is to show a thirty-minute pre-roll of strange clips and rarities relating (sometimes obliquely) to the main attraction. With The Peanuts Movie, though, the Alamo played things entirely straight, opting mainly for clips from the various cartoons, and never going for the most obvious or iconic choice. What blew me away, seeing some of these moments again for the first time in years, others for the first time ever, is just what a sharp and understated sense of humor Charles Schulz had. He was a master at constructing clever bits of slapstick, but also had an enormously keen eye for finding laughs in the simple interactions of children, or by inserting moments of surrealism or absurdity into everyday proceedings. That’s a gift The Peanuts Movie honors completely, and I found myself laughing pretty consistently from start to finish, rarely from big or overt gags, but from the quiet way in which the Peanuts world is inherently laced with humor. The screenplay was co-written by Schulz’s son and grandson, and you can feel that authorial DNA beating behind the heart of every laugh or moment of pathos the film has to offer.

The closest Martino and company come to giving in to modern Hollywood convention is with Snoopy and Woodstock, who could so easily come across as the non-sequitur sidekick characters upon which animated franchises are built (think the Minons of Despicable Me, or Scrat of Blue Sky’s own Ice Age films). Yet even there, things are played with such deftness and intelligence that Snoopy and Woodstock transcend the trends of 2015, and still feel utterly timeless. The film is careful not to let Snoopy enter his own separate side-film entirely, not only by letting him interact with Charlie Brown frequently, but by making Snoopy’s subplot – in which he envisions a fantasy adventure story with the Red Baron and his own new love interest – mirror the themes and turns of Charlie Brown’s story every step of the way. It’s a subtle but smart touch, and it means that whenever the film returns to Snoopy’s doghouse fighter jet, it never feels as if we have left the movie for ten minutes of slapstick pandering.

Perhaps the greatest surprise and pleasure here is the animation style, which faithfully recreates Shulz’s comic strip sketch sensibility in the realm of CGI. It is a difficult aesthetic to describe, with bold colors, simple backgrounds, and highly stylized character models, where hair and facial features look as though they have been drawn with pencil upon 3D figures; but it all looks amazing in motion, and feels like a very effective modern extension of what Schulz created in newspapers nearly 70 years ago. The film isn’t even afraid to take things to further levels of stylization when necessary, moments of hand-drawn sketching or visual abstraction lending the film a wonderful sense of aesthetic playfulness. It simply does not look like any mainstream CGI film I have ever seen, and given just how heavily homogenized CGI animation tends to be, that alone makes The Peanuts Movie worthy of serious praise.

Nor does the film sound like any other modern children’s movie, for Blue Sky has continued the Peanuts tradition of cast non-professional child actors in all the main roles. As always, the casting lends these characters a sense of authenticity and immediacy that is endlessly charming, and which goes such a long way towards letting us sink into the story. In particular, this film’s Charlie Brown voiced by Noah Schnapp, is one of the best, most effective voices Charlie Brown has ever had. One of the things both Schnapp and the writing bring out in the character is his underlying sense of optimism; it is a strange word to use when describing someone who is so often treated like fate’s plaything, constantly disappointed even when his ambitions are modest, but the fact that Charlie Brown perseveres, even when he is perpetually unlucky, is such a major part of what allows Peanuts to endure. The Peanuts Movie heaps on the existential torment in spades, its episodic narrative built upon an increasingly disappointing series of failures, but it also hones in on the optimism, allowing Charlie Brown’s creativity and determination to shine through just as much as his penchant for inefficacy. When Charlie’s spirit is seemingly broken near the end of the movie, it plays as something genuinely heartbreaking, because that discouragement strikes at the core of why we have come to love him as a character.

Of course, Charlie Brown finds out he’s all right in the end, and not since the conclusion to A Charlie Brown Christmas have I felt that particular Peanuts trope play out so beautifully. Martino and company earn the sadness, but they also earn the elation of triumph, even when ‘triumph’ here amounts to nothing more complex than successfully striking up a conversation. Most family films are built around some sort of seemingly universal theme, but when The Peanuts Movie evokes words like ‘discouragement’ and ‘perseverance,’ it means what it says, and it puts in the leg-work to earn the right to teach an important lesson. That this lesson potentially resonates just as powerfully for adults as it does for children, for dyed-in-the-wool Peanuts fans and newcomers alike, is perhaps the highest praise I can muster.

I have not written many film reviews lately, as I am sure you have noticed. A big part of that has come from other commitments – including a major project that I just completed, and hope to be able to talk about here soon – but part of that is also the feeling that, after eleven years spent reviewing movies, I feel myself running out of things to say about the current mainstream movie landscape, the good and the bad alike. There are only so many times, after all, that I can write a review bemoaning the state of what passes for children’s entertainment, or can phrase my frustration with Hollywood for treating kids with such obvious contempt. But in the case of The Peanuts Movie, I was itching to write about the movie from the opening moments, so completely does it buck every trend I have spent over a decade complaining about, and so infectious is its love for a property that remains, after all these years, so fundamentally simple. The Peanuts Movie is not the most groundbreaking or accomplished film of 2015, in animation or live-action, but for the specific ways in which it excels, and for the enormous heart beating beneath its surface, it may just be the most refreshing 90 minutes you’ll spend in a theatre all year.

Follow author Jonathan Lack on Twitter @JonathanLack.