Review: Robert Altman's "Popeye" is playful, sweet, and utterly singular

Movie of the Week #34

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie, with writing of mine that’s never been published online before.

Last week, in my “Animation and Identification” class at CU Boulder, I showed my students Robert Altman’s Popeye (1980). I considered it one of the bigger ‘risks’ on my syllabus, because it is, objectively, a weird movie, one that was not well-received in its day, and which has only recently started receiving a concerted rehabilitation effort. I figured my students would either love it or hate it, but of course, there’s only ever one way to find out. What I was sure about was that I had found the proper context in which to introduce the film: as part of a larger conversation on live-action remakes of animated material, a trend that is both impossible to ignore and, for the most part, absolutely soul-crushing. And Popeye is the right film to show for this topic both because it has been historically ignored, at least by the mainstream, and because it is the exact opposite of soul-crushing. Whether one winds up on Altman’s wavelength or not, you could never accuse Popeye of lacking a soul.

Thankfully, that screening went over like gangbusters – one of those magical evenings where everybody was laughing in all the right places, and I felt myself seeing more of the film than I’d ever glimpsed before because of all the good energy being exchanged between screen and audience. It’s one thing to show students a well-established classic and have them nod along approvingly; what’s really magical is sharing a film most of them didn’t know existed – “Robin Williams was in a Popeye movie? WHAT?” – and seeing them fall in love with it. I felt slightly self-conscious earlier in the week when I realized that the first Robert Altman movie I’d decided to teach as an actual Ph.D. was Popeye (in the same room where I’d once been introduced to the director through Nashville, no less); after hearing the students talk about the film, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

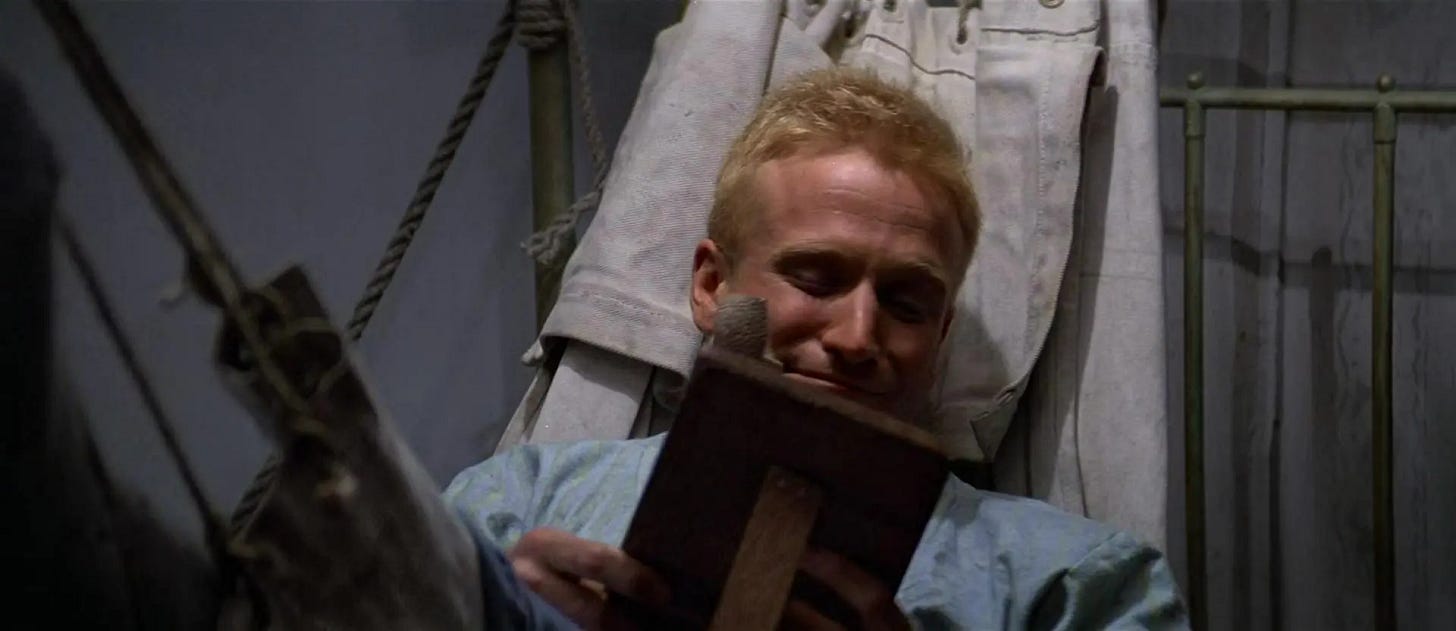

Popeye and I go way back, even though I’d never seen the film in full until Shelly Duvall passed away last year, and I put it on in her honor. I have extremely vivid memories of catching snippets of the film on HBO as a kid, on the big tube TV in our basement living room. I know I had seen the scene where Popeye and Olive Oyl discover Swee’pea in the basket, and I think I had seen Popeye’s “I Yam What I Yam” number. I had no idea the film existed before stumbling on it while channel surfing, and having my own moment of thinking “Robin Williams was in a Popeye movie? WHAT?” The film struck me, just seeing random scenes out of context, for how wholeheartedly it went about trying to be a live-action cartoon. I wasn’t even that familiar with the Fleischer shorts at that point, and I could still tell how singular the film was in play-acting cartoon logic on live-action sets. The way Williams held himself, hunched over, mumbling around that toy pipe, waving around those big forearm prosthetics; the way Duvall exaggerated her already wiry height to comic proportions, and pitched her voice in a way you would never hear out of a real flesh-and-blood woman. The slight irreality of the detailed, intricate sets, at once gritty and lived-in and cartoonish and impossible. The whole movie felt like a paradox. “Why didn’t I know about this?” I remember thinking to myself. “Why are there no other movies like this one?”

Maybe it took me so long to get back around to seeing the film in full for precisely that reason: because there really aren’t any movies quite like Popeye, and if you aren’t trying to actively remember it exists, it’s easy to chalk up as a crazy fever-dream. This is as strange and singular a film as has ever come out of a major Hollywood studio. As common as live-action adaptations of cartoons are today, it’s hard to understand how little most of these movies actually do to engage with the cartoon essence of their source material until one watches something like Popeye, which animates itself so earnestly and creatively. Altman is clearly fascinated by the challenge of recreating cartoon logic through live-action cinematic grammar. There is a playful ingenuity throughout in the way the film uses the tools of live-action cinema – mise-en-scene, bodily performance, simple special effects, and precise framing and editing – to recreate cartoon-style gags (see Popeye jumping in the ring, his boxing gear magically appearing in between the cuts, or the way the character turns into a literal rag-doll when hit or thrown to approximate the rubbery qualities of Fleischer’s animation). Altman is equally informed by the visual storytelling language of E.C. Seger’s original comic strips. The moment where Bluto literally “sees red” looking at Popeye, Olive, and Swee’pea – an effect achieved not with a red camera filter, but by painting every inch of the set red and costuming Williams, Duvall, and the baby in red clothing – is quite literally a comic-strip come to life, a joke predicated on creating and then undermining expectations in the same way a creative alternation of panels achieves.

If Altman’s Popeye has any real analogues, they’re probably Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (1990), Raja Gosnell’s James-Gunn-penned Scooby Doo (2002), and, from a totally different era and place, Tsuboshima Takashi’s Lupin the Third: Strange Psychokinetic Strategy (1974, which we reviewed on Japanimation Station). All are adaptations of comics and/or cartoons, and all are distinguished from the modern crop of Disney live-action remakes or Netflix recreations of animated TV shows by their complete disinterest in ‘realism.’ As Emily Stepp convincingly argues in this piece I assigned my students last week, those remakes all share a mission of ‘upgrading’ the original work; they play on nostalgia, even as they also denigrate much of what was beloved about their source material in an attempt to ‘improve upon’ or ‘modernize’ it. The small crop of adaptations Popeye belongs to are the exact opposite: they come from a place of deep and obvious love not only for their specific source material, but for the medium of comics and cartoons in general. They aren’t trying to bend the world of cartoons to the harsh logic of live-action cinema, but forcing the live-action world to play by the rules of cartoons – and that is no small difference. There is a special pleasure in films like this, that remind me of when I was a child on the school playground play-acting my favorite cartoons with friends. Imagination leads, and the result feels interactive, with everybody – filmmaker and audience alike – agreeing to set aside certain expectations and let a sense of childlike whimsy guide them. It’s a bit surreal, but deeply joyful.

Part and parcel to that affect is Altman’s deployment of tone. ‘Playful’ may be the single best word to describe Popeye, but if there’s a runner-up, it’s probably ‘sweet,’ and/or ‘earnest.’ There is no hint of irony anywhere inside this film. It never adopts a ‘winking’ affectation, and it never thinks itself above the material; nor does it feel the need to ‘outsmart’ or crassly modernize Popeye and friends to justify its existence to the most cynical members of the audience. It is a profoundly silly movie that loves being silly, just as much as it authentically loves these characters. And from that love flows very real and resonant pathos: In the Swee’pea plotline, the Popeye/Olive Oyl romance, and Popeye’s search for his long-lost Paps, there is an earnest belief in the hearts of these characters, a passionately developed theme about the simple power of finding that special person who needs you, whether as a caretaker, a partner, or a parent. Robin Williams isn’t just the right person to play Popeye because he can do the voice and contort his body to look the part: it’s because he’s so naturally funny that he can get away with being completely, profoundly, disarmingly sincere in his interactions with Swee’pea – that he can call himself Swee’pea’s mother and not play it at all as a joke, but as a self-affirmation of newfound purpose. It is funny, of course, but it’s the kind of laugh that feels warm inside; it isn’t funny that Popeye sees himself this way, it’s funny that Popeye doesn’t have a care in the world for how anyone else sees him when he’s got this baby to take care of.

It goes without saying that Altman’s Popeye is gorgeous to look at. If there is one constant in reactions to the film over the years, it’s that the creative team went above and beyond in building out the town of Sweethaven as thoroughly as they did. I truly think it’s one of the great feats of cinematic production design I’ve ever seen, a fully-realized, wholly tactile world. Every exterior, every interior, every bit of set dressing all feels bespoke and of a piece, the kind of filmic environment you want to walk into the screen and explore. Altman approaches his mise-en-scene here with every bit as much formal rigor as he did McCabe and Mrs. Miller, a film to which Popeye bears more than a few structural similarities. Altman explores exterior and interior space with such exacting attention that we do not so much visit his worlds as we fully inhabit them, firmly rooted in a specific time and place – even if that time and place are, in this case, thoroughly imaginative. I had a Professor at CU Boulder – the one who introduced me to Altman – who said that the three hours spent watching Nashville truly felt like spending five full days in the city. He didn’t say this critically (as in, ‘the film is so slow it feels 120 hours long’), but with a sense of awe, as in ‘there is something in the unquantifiable artistic alchemy of this thing that bends space and time in on itself and makes you feel as though you’ve been on a very real journey that belies the mundane reality of sitting in a theater for 160 minutes.’ I think he was exactly right about that, and I would borrow his line to apply to Popeye, too. Even though Sweethaven isn’t technically real (although you can visit the set, now called ‘Popeye Village,’ still standing in Malta as a tourist attraction), two hours in a dark room screening Altman’s Popeye does feel like one’s spent a week vacationing on this strange island of cartoons come to life.

And it really bears underlining how much Popeye is a Robert Altman movie through and through, warts and all. It’s full of densely layered, overlapping sound that is sometimes hard to parse; is captured in widescreen with lots of reframing, including many zooms in and out; and continually returns to busy ensemble set pieces, like the dinner at the Oyl household or the scene at the ‘horse’ races, where a million things are going on at once, our attention is constantly buffeted by the sheer amount of action, and yet instead of feeling aimless or out-of-control, there is a finely orchestrated quality to the chaos, a sense of a great artisan pulling the strings to masterfully puppeteer the ensemble and their mise-en-scene. This is key to how Altman achieved such a singular sense of immersion: his films are so richly populated, so dense and full of life, that you come out of every scene just on the edge of exhausted, in a space that feels more like exhilaration. Altman’s affect also matches the attitude of the Fleischer cartoons, in that Popeye mumbling over the action, or he and Olive speaking past each other simultaneously, is a feature of those classic shorts, one it’s hard to imagine another director – past, present, or future – being quite as well-suited to recreate (other than maybe Paul Thomas Anderson, who famously used the Popeye song “He Needs Me” in Punch Drunk Love, and whose inimitable Inherent Vice strikes me, thinking about it now, as something of a spiritual descendent).

Of course, Altman got lucky that at the moment he made Popeye, the two most perfect possible actors for the assignment were alive, available, and at the correct ages to play the lead roles. I cannot imagine anyone but Robin Williams pulling this character off, and it’s even harder to conceive of anyone other than Shelley Duvall making a live-action Olive Oyl work so perfectly. I adore them both here. I love Williams’ constant mumbling over the movie, the convincingly rubbery way he moves his legs, his full-throated commitment to the part – and also that indescribable sweetness and humanity he brought to every role he ever played. Duvall, meanwhile, makes this ridiculous lanky cartoon damsel come to life in ways that are both consistently funny and heartfelt, with the “He Needs Me” number threading that needle to astonishing effect. This film and The Shining came out about six months apart, and while Duvall’s work in both wasn’t fully appreciated at the time – and still isn’t, by certain assholes on the internet intent on willfully misinterpreting her work in Kubrick’s film – I’d contend it’s one of the strongest one-two punches you’ll find from any performer in her generation. God, what an actor!

Speaking of the Harry Nillson songs, I love those too. They’re weird and sometimes sort of mumbled and lyrically bare, but they fit the movie, and they create a real sense of character and place, and sometimes they come together in really dynamite pieces of filmmaking, like “He Needs Me,” or Popeye’s big “I Am What I Am” number. And I don’t think I can properly express in words the joy sparked by seeing Nillson build a song around Wimpy’s iconic, silly catchphrase, “I will gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.” Just typing it out, the melody bounces through my head. The choice to do this as a musical pays dividends, foregrounding the film’s sweetness and playfulness from the very beginning.

Is the film perfect? Of course not. The whole thing is fairly episodic and meandering, though I don’t see that specifically as a problem. It’s based on a series of cartoons and comic strips, after all – a narrative form based on short bursts of gag-driven action – and most of Altman’s movies are sort of loose and meandering, or at least feel that way in the moment, and that’s generally seen as a feature, not a bug. What Popeye lacks is a moment like the end of Nashville, where Altman pulls the strings taut and every second you’ve spent in this world drills down to a single impactful punch; or, if not that, a stylistic shift a la the climax to McCabe and Mrs. Miller, where a loud, sonically dense movie becomes very quiet and aurally precise for its last 20 minutes. I’m not sure either of those approaches would work for Popeye – this movie would not be improved with Wimpy getting assassinated just before the credits rolled – but the last 20 minutes are fairly slack; there are a lot of shots held longer than feels natural, with a lot of extra ADR (in a movie that’s already heavily dubbed) papering over the lack of close-ups and coverage, a byproduct of Altman essentially running out of money and being ordered to return to America before finishing the climax. Whatever the reason, it feels like there’s a final gear missing, one last mode the movie needed to shift into at the end to fully articulate itself, and it never quite gets there.

Then again, there is something ludicrously charming about a movie that goes out on Popeye fist-fighting an octopus puppet, singing a song, and winking at the camera in the corner of the screen, such that my film-analyst brain can only be so critical. It’s simple, it’s fun, it’s lovely – it’s Popeye. There is no other movie in existence remotely like this one. Like Popeye himself, it’s undeniably odd and misshapen, moving and talking entirely to its own patterns and rhythms; but as with the eponymous sailor, how can you not love something that is so thoroughly one-of-a-kind? It yam what it yam, and I love what it yam.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.