Review: Robert Eggers' "Nosferatu" is startling, pervasive, and powerful horror

A grisly and disturbing Christmas present

Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu is a remake of the landmark 1922 German expressionist film of the same name by F.W. Murnau – and a fairly faithful one in many respects – but it is also, as Murnau’s film (illicitly) was, a retelling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which means it belongs to the larger corpus of Dracula adaptations that all share the same basic set of plot points: A young real-estate agent (Jonathan Harker, here called Thomas Hutter) travelling to Transylvania to help a mysterious Count (Dracula, here Orlok) buy property in England (or Germany); the Count ensnaring the young man in his castle before travelling back to the homeland; the Count’s obsession with, and attempted seduction of, the young man’s betrothed (Mina, here Ellen, already his wife); and the entrance of a brilliant but eccentric foreign Doctor (Van Helsing, here Von Franz) who helps the returning Harker/Hutter and his friends vanquish the Vampyre. The fun of watching Dracula retold over and over again lies in seeing how each filmmaker takes these basic building blocks to construct works that are often radically different in tone and theme. Murnau’s Nosferatu is, as its subtitle tells us, “A Symphony of Horror,” a nightmare captured on celluloid (I once saw it projected in a grand Denver Cathedral with an accompanist playing the Church’s grand organ alongside it, and it was a truly out-of-body experience); the 1931 Universal Dracula is theatrical and melodramatic, much more verbal and literal than Murnau’s vision, and centered primarily around Bela Lugosi’s iconic, larger-than-life performance; Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, which I wrote about back in September, is a psychosexual revelry, uninhibited both in its expressive visual design and its extreme sexual charge.

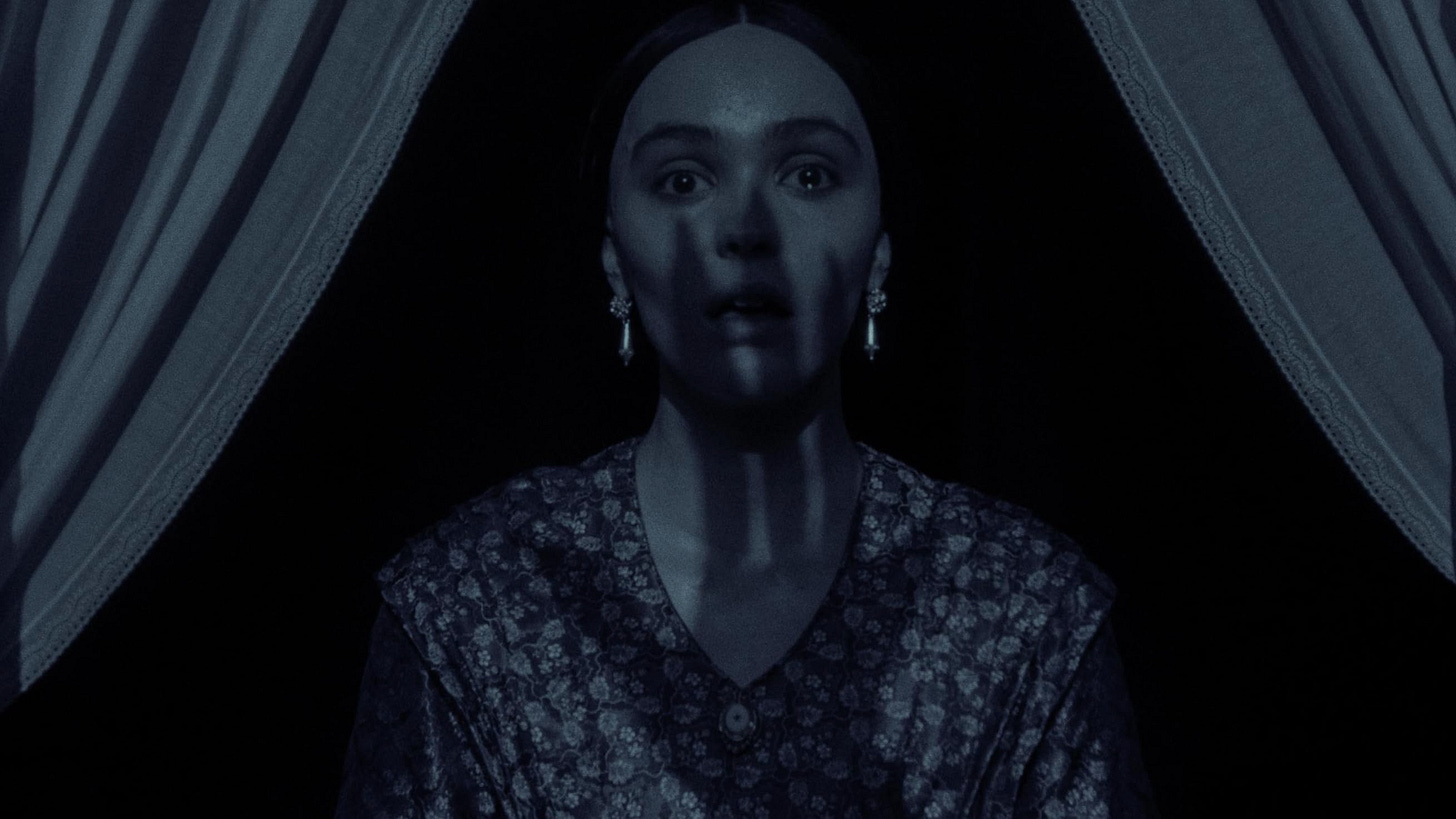

Eggers definitely hews closer to Murnau than most other adaptations, both in narrative detail and in stylistic conceit; the film draws heavily from German Expressionism, particularly in its use of shadows and lighting (and in several scenes where diegetic frames-within-frames, such as doorways, provide similar effects to Expressionist iris shots), while also tipping its hat to other European silent horror of the period (there is a breathtaking moment during Hutter’s journey to Orlok’s castle that pays direct homage to Victor Sjöström’s 1921 Swedish masterpiece The Phantom Carriage). The core gambit that sets Eggers’ vision apart, though – and it’s something I’ve never seen in a Dracula adaptation before – is that he largely minimizes the Vampyre himself as a physical presence. Count Orlok is here, played to truly terrifying effect by an entirely transformed (visually and vocally) Bill Skarsgård (who, between this and the two It films, where he played Pennywise, has carved out quite the niche for himself as disturbing horror icons). But apart from the very last scene of the film, Eggers never lets us get a particularly good look at Orlok, keeping the Count at least half in shadow at his most visible, and more often blocking scenes so that we are watching characters react to the Vampyre, and not seeing the Count’s body ourselves. In the glimpses we do catch, this is a particularly deformed, decayed, and corpse-like vision of Dracula, rotted, fetid, and revolting.

Yet those glimpses are few and far between, and in place of the body, the terror of Nosferatu becomes a much broader presence, an intangible atmosphere, a specter haunting these people and spaces and the images of the film itself. This is how Dracula is often described to us, in Stoker’s writing and subsequent adaptations – as a force of evil larger than a single person or body – but film versions are often so married to the actor playing the Count (for understandable reasons, given the line-up of legendary actors who have played him) that we do ultimately understand him as an individual, not as a larger, disembodied force of cosmic evil. Murnau’s Nosferatu was certainly invested in this idea too; Max Schreck’s performance is iconic, but he isn’t front-and-center the way Lugosi or Christopher Lee are in their versions, and the plague of rats Orlok brings to Germany with him suggests a much larger toxic force threatening this world (which has since opened that film to readings of historical anti-Semitism, for how it visualizes a foreign pestilential invasion of the homeland).

But Eggers really nails this idea, of ‘Nosferatu’ as a horror unbound by physicality; it invades and infects the body, but also tortures the mind, creeps into every dark corner, seeps into dreams and erases the line between sleep and wake. He uses all the tools of filmmaking at his disposal, all its possibilities of visual expression, to captivate us into a very particular mood. Jarin Blaschke’s cinematography is technically in color, but so drained of vibrancy that it often looks monochromatic; combined with extremely low lighting and deep, pervasive shadows, we are often looking at images being overwhelmed by darkness, fighting to see clearly through the miasma. In lesser hands, this could be disastrous (and certainly, if your theater hasn’t replaced its projector’s bulb in a timely manner, the effect might be undermined); but in Eggers’ vision, we become lost in the image, terrified by what we cannot see, overwhelmed by the cold, oppressive atmosphere. Careful and precise sound design, echoing with a depth that makes those shadows feel even more vast and all-enveloping, along with a truly great score by Robin Carolan that is rich in pathos and dread, work to further shroud the viewer in the affect of dreams and nightmares. The first hour in particular is so purposefully slow and dreamlike, I found it lulling me to sleep; I never quite nodded off, but I felt like I was being bidden to do so, not out of boredom, but by the quiet intensity and uncanniness of the sounds and images. I felt increasingly out of sorts as I fought to stay conscious, terrified not only at how the film blurred the lines between dreams and reality, but at my body’s own acquiescence to the shadowy web of inescapable terror Orlok draws around these characters. As evinced by the biggest change both Murnau’s and Eggers’ Nosferatu make to Stoker’s Dracula – that the Vampyre cannot, in the end, be physically vanquished through force – Orlok comes to seem less like a discrete on-screen character than a specter floating through the darkness, invading the mind and chilling the air, extending past the screen to be felt in the space of the theatrical auditorium itself.

As in The Lighthouse or The Northman, Eggers is monomaniacally focused on evoking an extremely specific, extremely intense tone, one that is in this case unrelentingly dour and genuinely quite frightening…except when it is also slyly funny, which has always been the other half of the Robert Eggers magic trick. He is so tonally adroit, committed deeply to the macabre, the mythical, and the melodramatic, that in so doing he also finds ways to make us laugh, not because his films stop to wink at us, but because they understand how fear and humor, melodrama and comedy, and terror and laughter are all so closely related that they can be activated in tandem. Eggers’ films never pause for moments of conscious ‘release’ from the tonal pressure he builds, but I find myself reaching moments of rupture myself, where the terror and intensity grows to a point where I burst out laughing, almost in spite of myself.

A big part of this is Eggers’ mastery of language. He is one of the 21st century’s greatest writers of cinematic dialogue, unfailingly and uncannily able to evoke the language of the periods or mythos he works with, in a way that sounds like these words were pulled from an ancient book recovered from a crumbling tomb (to put it another way, while much of the dialogue in Nosferatu isn’t pulled directly from Stoker or Murnau, it often sounds like it was, effectively inhabiting the voices of writers from a century or more prior). Sometimes Eggers’ combinations of words strike terror into the heart, in this sort of grand Old Testament way, like the words of a dark God meant to humble us; and sometimes they travel so far down this path, are so over the top in their verbal evocations of evil, that their balletic complexity makes us laugh. Oftentimes, I find Eggers’ sentences do both at the same time. Willem Dafoe is Eggers’ greatest partner and asset here, as he has been before. His Von Franz is a tremendous, remarkable performance, perfectly straddling that line wherein he is both the figure who most imparts the severity of Nosferatu’s threat, and the one who most frequently produces laughter. Dafoe is simply possessed here, far and away the best version of Van Helsing I have ever seen on screen, and if nothing else in the film worked, it would still be worth seeing for him alone.

But of course, we have long since come to expect startling greatness from Dafoe. The film’s true revelation is Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen, the Mina equivalent who is the ultimate object of Orlok’s schemes. She is a force of nature, modulating from extreme buttoned-down propriety to so overflowing with rage and grief and passion that her body can barely contain it. Every Dracula rendition can be measured, to some extent, by its treatment of the story’s inherent sexual qualities; here, Eggers has constructed his Nosferatu as a grand, damning expression of sexual shame. The true root of its horror – the true force that makes Orlok such an all-encompassing terror, free to invade one’s dreams and make even daylight feel cold and dark – is the dread that comes from bottling up desire and rendering it a shameful secret, a disgrace to be guarded and ignored.

The film is about 19th-century attitudes towards women – the word ‘hysteria’ is purposefully and pointedly employed in the many ways the men around Ellen try to understand her affliction as anything other than what it is – but in so doing it is also, of course, about 21st century attitudes, and the destructive force that is willful male ignorance. Stoker’s Dracula has a ‘happy’ ending, for Jonathan and Mina at least, one in which domestic harmony is restored; Murnau’s Nosferatu does not, and that refusal to see this story as one in which such harmony can or should be reestablished is, as much as any aesthetic component, what unites Eggers to this specific 102-year-old telling. The most disappointing part of any Dracula adaptation, to me, is almost always the ending; there is an inherent anticlimax in the relative ease with which Dracula is vanquished, and especially in the apparent ease with which the survivors move on with their lives. This story doesn’t feel like one that should be wrapped up with such a neat and tidy bow. Eggers’ refusal to give easy answers or offer reassurance makes this, perhaps, my favorite finale of any adaptation. And one can clearly see a throughline in his work, the tragedy of female sexual repression here feeling like a flip side to how Eggers treated unfulfilled (and perhaps unfulfillable) male desire in The Lighthouse. Eggers’ Nosferatu ends on a note that is at once horrifying, disgusting, and quietly cathartic; one might even call its extraordinary final shot ‘beautiful,’ in the gothic sense of ‘beauty’ as an aesthetic force, a strength of expression and compositional rigor that sparks a wide and messy range of unresolvable pathos.

I loved this film. I cannot wait to see it again, ideally on a better screen with more capable contrast (seek out Dolby Cinema or something with laser projection, if you can, as these are the theatrical formats with the greatest contrast ratios; I suspect the film will also be tremendous demo material for OLED screens when it reaches home video). I haven’t even found room here to sing the praises of Nicholas Hoult, who might well be the most compelling take on the Jonathan Harker character I’ve seen (it’s an incredibly thankless part in most adaptations, the good upstanding man who primarily serves as a contrast for the temptations Dracula offers Mina, but Hoult gives him a personality and soul, as he is always so good at doing). This is a film that, like each of Eggers’ works up to now, will take more than one or two viewings to start fully digesting, and it further cements him as one of the single most exciting filmmakers working today. I cannot wait to see what he does next.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.