Review: “Sherlock Jr.” – 10 Lessons from 100 Years of Buster Keaton’s Classic

Movie of the Week #21

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column (coming out Thursday this time) where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week for paid subscribers. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of attending the Denver Silent Film Festival at the Sie Film Center. There were many wonderful films and programs over the course of the weekend, but I think the screening that left the greatest impact on me was watching Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. with a sold-out house, and seeing this silent comedy that is literally a full century old this year absolutely kill with a group of people in 2024, from start to finish. There are of course silent comedies that haven’t aged well – this screening was preceded by Keaton’s The Play House (1921), a film whose copious amounts of blackface make the humor difficult to engage with – but Sherlock Jr. is one of those classics that is truly timeless.

In fact, while watching, it occurred to me that so much of what can be learned or said about movies is contained within the relatively scant 50 minutes of Sherlock Jr. Plenty of filmmakers still learn all sorts of lessons from Buster Keaton, and proudly wear his influence on their sleeves. In fact, my two favorite movie franchises of the 21st century – Mission: Impossible and John Wick – would not exist without Keaton, as the films themselves proudly tell us: Dead Reckoning’s final act riffs on many different train movies, but is principally indebted to The General, while John Wick: Chapter 2 opens with none other than Sherlock Jr. being projected on the side of a building, explicitly tying the mayhem to come to a century of Keaton’s echoes through film history.

There are, suffice it to say, countless lessons to be learned from Keaton’s filmography at large, and from Sherlock Jr. in particular. But in honor of the film’s 100th anniversary, here are 10 lessons that struck me, about how movies are made and, just as crucially, about how movies are watched.

1. Structure matters, even (or especially) when it is upended

Sherlock Jr. is an oddly structured film. It tells one story, of a young man (Buster) trying to woo a love interest (Kathryn McGuire) until he is framed for theft by a rich rival suitor (Ward Crane), for about 18 minutes, at which point it transitions to a long, elaborate dream sequence where the boy imagines himself as a great (albeit unorthodox) detective having an increasingly outlandish adventure. This dream sequence lasts for over 25 minutes, only returning to reality for the final 5 minutes of the picture, where the first story is resolved. In fact, the resolution of the ‘real’ story is planted just before the dream begins, as Buster’s love interest, sensing something is off, goes to the pawn shop where Buster supposedly sold her father’s watch and learns the rich suitor was, in fact, the culprit. So the matter of Buster’s innocence is actually already taken care of (for McGuire’s character and the audience, if not Buster himself) before the dream even begins. Thus, Keaton suspends the forward momentum of the first plot just before its ultimate point of resolution, interrupting it with a different, more complex and comical plot in the dream, which is fully articulated and resolved before Buster wakes up for the final beat of the first story.

Needless to say, when one breaks the narrative down like this, it is clear no screenwriting manual would ever tell you to structure a film like Sherlock Jr. It is an odd and atypical shape even for a silent comedy. The film opens with “an old proverb which says: ‘Don’t try to do two things at once and expect to do justice to both.’” This is nominally about Buster’s character working as a projectionist while he tries to be a detective, but it also reads as something of a dare from the film to itself, as Sherlock Jr. is not only telling two stories, but connecting the protagonist’s two vocations through the film’s two primary vectors of humor: Detective parody, and reflexive play with the nature and substance of cinema and spectatorship. In this way, the film is actually quite deeply structured – one side always helps articulate the other, the reflexive qualities enabling the outlandishness of the detective parody, and the absurdity of the detective plot fueling our awareness of the spectatorial play – but that structuring is wholly unconventional. Sherlock Jr. upends conventional narrative structure while displaying a deep understanding of how stories are told and where audience expectations lie; structure can be upended, but it cannot be ignored – form always matters. Sherlock Jr. is not purely anarchic, but quite wise in understanding form and structure and where and how they can be played with. Which brings us to our second point:

2. Conventions are made to be broken

Think of this lesson like the principles of rhythm and variation in music; a great pop song, for instance, needs a great bridge, a point in the progression where we break the established patterns and play with their shape and character. This is true in cinema, too. The master of patterns – which all great filmmakers to some extent are – will typically build their patterns to eventually be toppled; conventions become a playground, building blocks for creating new shapes.

Keaton does this in all manner of great ways in Sherlock Jr., of course. The central gesture of Buster stepping into the screen, with jump cuts transporting him between locations and scenarios (a moment we will attend to more closely in a later point), is entirely predicated on first establishing and subsequently breaking conventions of film language.

But here, I want to draw our attention to one scene specifically, as it so simply yet perfectly encapsulates this lesson. About 33 minutes in, we visit Sherlock Jr.’s home, as his assistant Gillette helps him get ready for the day. First, we see Sherlock finalizing his look in a doorway, which we initially believe is a mirror due to the carefully crafted symmetry of the mise-en-scene on either side; but then Buster walks assuredly across the threshold and we realize this is a bizarre coincidence. Without any edits, movements of the camera, or alteration of the scenery, our sense of the frame’s spatial dimensions are suddenly upended, almost like looking at a Magic Eye painting and finally seeing the image coalesce into three dimensions. Buster then goes to open a large safe in the wall, and even though we have just been tricked, we still find ourselves astonished when he opens it not to reveal a small compartment with a gun or jewels, but the outside world; the safe is his front door, which he absurdly locks from the inside like this. In neither instance is Keaton the filmmaker lying to us; he is simply establishing familiar imagistic conventions and then boldly defamiliarizing them, to our astonishment and delight. The effect is like an excellent magic trick.

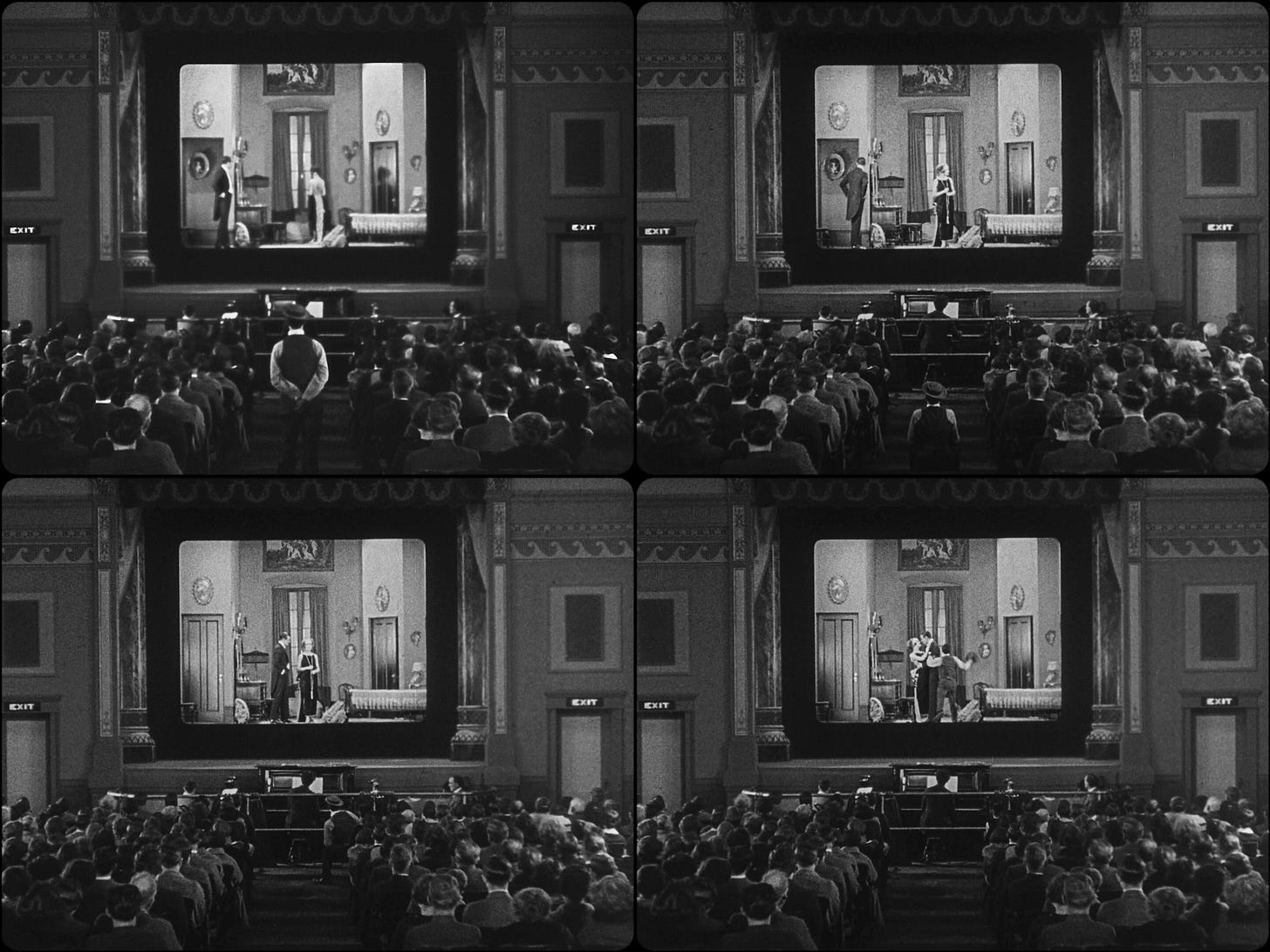

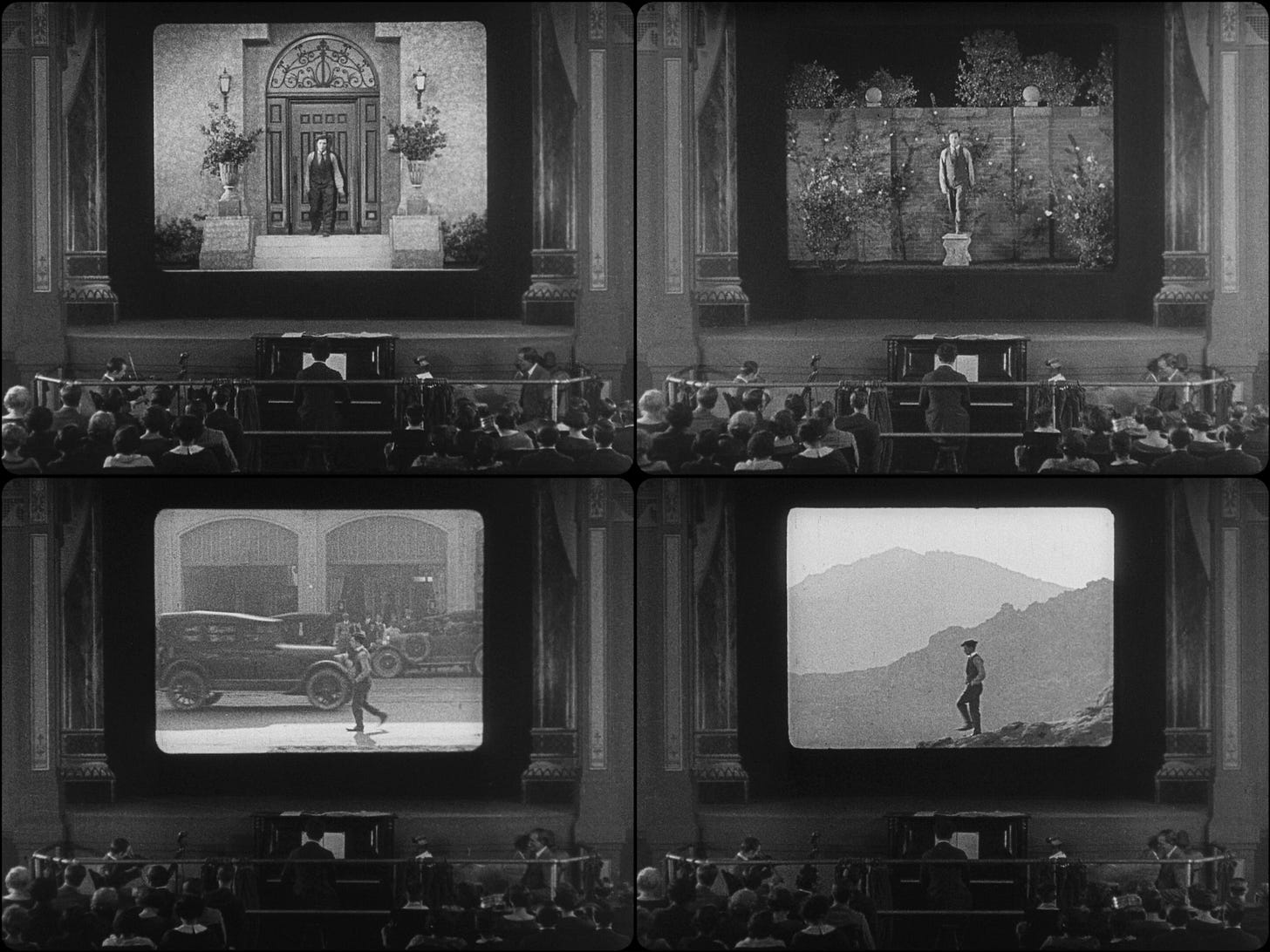

3. The best special effects (and stunts) bear the affect of a great magic trick

Indeed, there is something of a stage magician’s confidence to all the best moments of ‘trickery’ in Sherlock Jr. Look, for instance, at the length of the shot where Buster’s ‘dream self’ first steps into the screen and enters the movie. He first walks into the auditorium, and observes while standing in the back; then he sits down in the middle of the aisle to watch for a few beats; next he gets up and comes closer, taking an empty seat in the front row. All the while, Keaton the filmmaker is using both duration and our identification with Buster as a spectator to acclimatize us to the way the shot is set up, to the illusion that this is, indeed, one pre-recorded image being projected within the frame – which makes it all the more breathtaking when Buster stands up from his seat in the front row, walks onto the stage, and steps right into the film, breaking a barrier the filmic grammar had made us think was insoluble.

There is a magician’s hand at work here. Keaton must establish a certain mundane reality – the sense that there’s ‘nothing up my sleeve’ – before he proceeds to casually shatter that reality with little more than a flick of the wrist. The casual, almost off-hand showmanship of Buster Keaton is, of course, crucial to what continues to endear him to us a full century later. His stunts are always performed in the fullness of time and space – long shots of great duration – where we see his body play with the scenery as though little exertion is required. The bit on the train early in the film – where Buster goes across the top of each car and finally grabs the water tower to swing himself down, only to get doused – is so casually breathtaking, done entirely in one unbroken take where we can easily perceive the reality of his actions. Keaton later one-ups himself on the other end of the film, in the shot where he looks for several ways down from a roof only to grab onto a large swinging gate and land in the back of the villain’s car. That the gate is clearly visible throughout the shot – obvious in our field of vision while Buster looks for less unlikely means of escape – adds to the illusion that this is improvisatory and off-the-cuff. Of course this is all carefully choreographed; but in the moment, it feels like a magician has just nonchalantly pulled a rabbit out of the hat, casually ignoring the laws of physics to bend reality to his will. The confidence is in and of itself part of the trick.

4. Graphic matches were arguably cinema’s first “special effect,” and remain one of its most powerful

Speaking of special effects, we must pay tribute to Keaton’s use of graphic matches – what Bordwell & Thompson define as the editorial effect of “[linking] shots by close graphic similarities.” These are a staple device of any editor’s toolkit, but their possibilities for surprise and astonishment have delighted filmmakers since the formative days of cinema. Think of the joy Georges Méliès displays in his early shorts, realizing the edit could be used to perform magic tricks. Here he is in 1898’s The Four Troublesome Heads, using match cuts to make it look like he is taking off his own head and placing it on a table. There is a stage magician’s flare to the whole thing, but fueled by a power unique to cinema: the ability to excise time, and seamlessly transform the body and environment in an instant, between two adjacent frames:

Stanley Kubrick’s use of the graphic match in 2001: A Space Odyssey is perhaps the most famous piece of editing in narrative film history, as he leaps across the entire history of human development in a single cut between a bone thrown by proto-human apes and a nuclear satellite orbiting earth in the near-future. We are perhaps unaccustomed to thinking of graphic matches as a ‘special effect’ today, but as a bold expression of cinema’s most basic and indelible trait – the ability to cut, to connect time and space within a fraction of a second – that is exactly what they are.

Keaton, of course, uses them beautifully in Sherlock Jr., in the sequence where Buster steps into the film and keeps being tossed between locations and scenarios. These remain some of the most perfect, startling graphic matches of all time – so perfect, in fact, that they seem fully imperceptible and seamless, unless one advances frame-by-frame to examine the exact moment of transition. While watching at full speed, however, the illusion is total. How Keaton achieved these images is no mystery – he carefully matched the spatial dimensions of adjacent shots so that the entire sequence appears to us as one unbroken take, in which his character is transported between scenes – but the power of the cut is so immense, in its centrality to filmic grammar and the way we understand cinematic narration, that we accept the effect on a purely subliminal level. Even when going through this sequence on repeat to write this analysis, with the method of its making at the front of my mind, I cannot question the ‘reality’ of what I see: Buster has, simply, teleported. Few, if any, cinematic special effects are this rock solid and undeniable, because none of them are predicated on such a fundamental quality of film language.

5. Dialogue is an often unnecessary luxury

This is a lesson many of the great silent films teach us, of course. But as one of the best of the best, Sherlock Jr. is a particularly adroit teacher. Look at how much the film communicates to us with so few intertitles. The framing, body language, mise-en-scene, and editing are so wonderfully communicative that the absence of spoken words and synchronized sound is no absence at all: the film could not be improved by their addition. Think, for instance, about the early episode with Buster finding money in the theater’s garbage. So much character is revealed here, completely wordlessly, in a way that creates a strong empathetic connection between Buster and the audience. The character’s simultaneous reluctance and decency is encoded in Keaton’s physical performance; I am particularly moved, to both laughter and sympathy, by the way he defeatedly mimes the shape of a dollar bill to the second woman. There is no dialogue Keaton could have given his character here that would make us understand him better.

Now, this is not to say that good dialogue is not a major boon to the countless sound films that boast it, or that there aren’t whole swaths of filmmaking styles and genres that would be impossible without synchronized sound. My point is simply that whenever we go back to a great silent film, we are reminded of just how much can be communicated through everything else, through the purely visual aspects of cinema; and this forces us to question, I think, whether those tools are being used to their fullest extent in the films we watch today. For every film that makes virtuosic use of sound, there is surely another that leans on it as a crutch, leaving vast possibilities of visual expression untapped (at this point, most Marvel movies could work just as well as radio plays, and are these days so ugly they might in fact be improved by removing the visual layer altogether).

6. The power of planting and pay-off

A basic concept of narration in many different mediums, but particularly important to cinema in the ‘body’ genres of comedy, thriller, and horror, planting and pay-off is an essential tool to understand; and while there are many films that execute upon it masterfully, I’m not sure any do it in as teachably perfect fashion as Sherlock Jr.

There are three particular bits of planting and pay-off I want to highlight, and all happen on unique time horizons. The first is a banana peel gag near the beginning, all contained in a single unbroken shot: Buster lays out a banana peel to trip the rival suitor, beckons the man in, is thwarted when the suitor fails to step in the right place, and stands up in a huff, only to trip on the peel himself. A perfect concentrated burst of physical comedy: establishment, frustration, and culmination, all in the span of about 45 seconds.

More complex is the gag in the dream sequence where Buster and Gillette lay out their absurd device with a hidden costume. They place it in the window of the criminals’ lair before Buster goes in, and at the time, the viewer has no idea what is inside, or what its purpose might be. This time, though, Buster allows us to forget this mystery he has planted, as the scene inside the lair goes on just long enough, with other tension displacing the mystery of the device in the window – including a cutaway to reveal the kidnapping of Buster’s love interest – that when Buster makes his dramatic escape and suddenly jumps through the window to come out the other side disguised, the moment is both surprise and resolution: A seeming non-sequitur that turns out to be the answer to a briefly dislocated mystery. The result is one of the film’s best and biggest laughs.

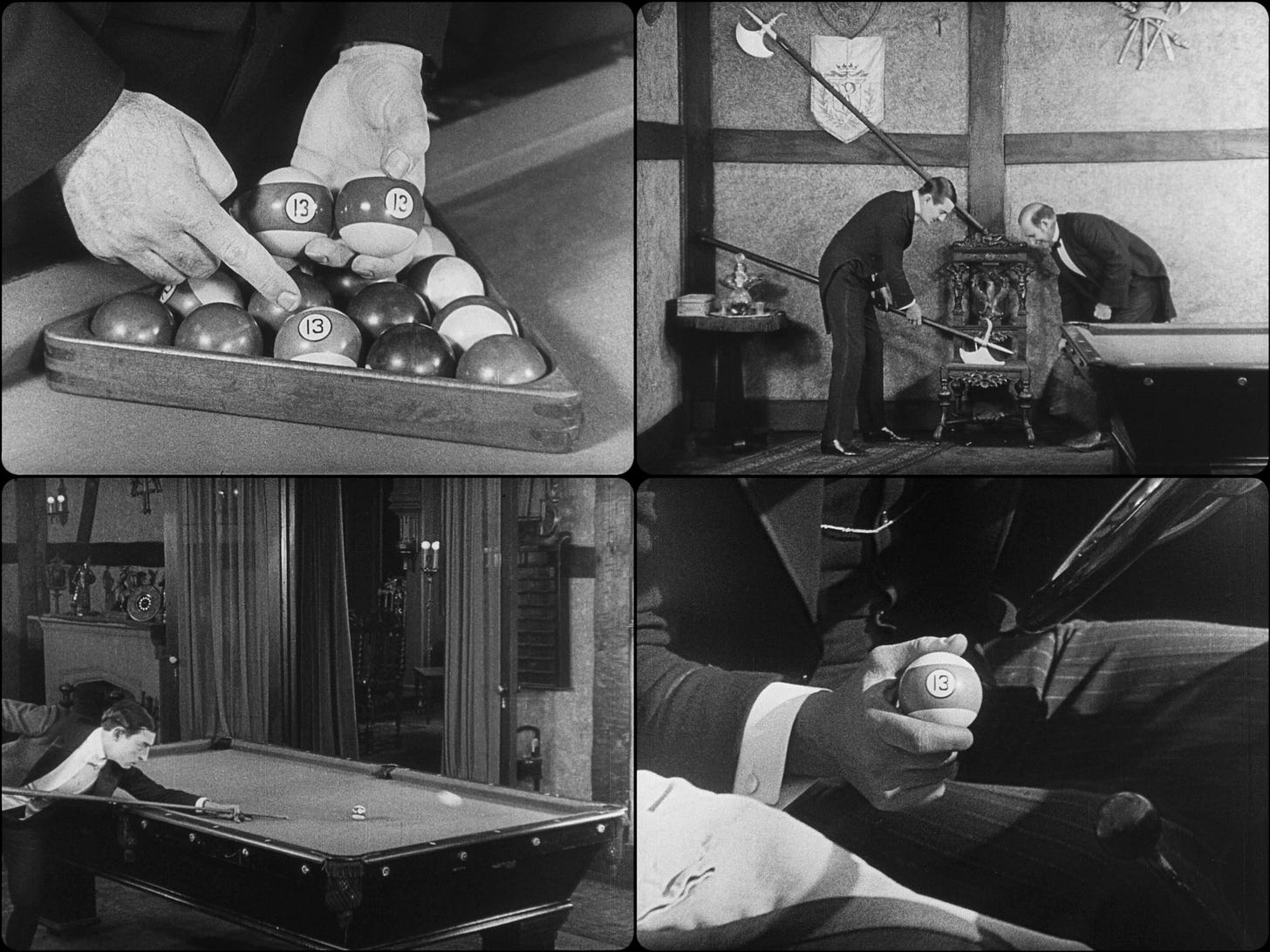

Most perfect and elaborate is the saga of the exploding cue ball, one of the traps the villains lay out for Buster when he visits the manor as Sherlock Jr. These traps are established for us just after the 25-minute mark, and when Buster enters the room a few minutes later, the film exhibits a masterclass in the theory of tension Alfred Hitchcock would articulate many years later, in this 1970 AFI seminar:

Hitchcock’s theory is that the sudden explosion of a bomb provides a momentary shock, while the reveal of a bomb before a long and otherwise mundane scene transforms that mundanity into constant tension. This is exactly what Keaton achieves here, as Buster narrowly avoids the axe, the poison, and then miraculously plays an entire game of billiards without triggering the exploding cue ball. This is planting with no pay-off – the bomb keeps refusing to go off – which transforms tension into comedy (and in so doing reminds us how closely aligned these principles are – comedy, thrills, and horror are all bodily reactions, and the skillset for achieving them is therefore quite similar).

The final pay-off to this sequence comes much later, a full twenty minutes after the exploding cue ball is introduced, when Buster pulls it out of his pocket during the climactic car chase and uses it to topple his pursuers. This is the last major beat of the dream sequence’s action, and that it ties back to one of the first elements laid out in the dream makes it all the more satisfying; when viewed with a large crowd, I’ve seen this moment produce both laughter and cheers. Keaton’s mastery of planting and pay-off is so total, and so varied in its deployment over the course of the picture, that the audience is constantly being rewarded, in different ways, for their investment. It’s a lesson with broad applicability not only for comedies, but any narrative film predicated on closely engaging the viewer.

7. Sometimes a joke gets funnier the further you push it

You can see this lesson at work in two major sequences of Sherlock Jr., where Keaton starts with a simple scenario and keeps riffing on it until he’s pushed well beyond any initial expectations. The first is the aforementioned game of billiards, where we see Buster sink every single ball on the table while waiting with bated breath for the explosive ‘13’ to be hit. The situations in which it doesn’t get hit just keep getting increasingly ridiculous – climaxing with Buster hitting the cue ball up and over the 13 in a perfect arc – until we aren’t so much fearing the bomb going off, but leaning forward in anticipation wondering how Buster is going to miss the 13 the next time. When I saw the film in a giant, sold-out auditorium earlier this year, this sequence just killed, getting increasingly uproarious laughter as the stretching of the tension transforms into outright absurdism. In the end, the 13 doesn’t explode even when hit – which actually, returning to Hitchcock, anticipates what the Master of Suspense himself would tell us 46 years later, when he ends the above clip by insisting that the bomb must never go off. Keaton does eventually let the bomb go off, but on the other end of the film, when Buster pulls it out at the last minute in the final car chase, a moment that feels miraculous as a culmination to so much delayed and disrupted tension.

But the principle of wildly extending a joke is shown in even more spectacular fashion in the chase sequence where Buster winds up riding alone on the front of the motorbike, after Gillette falls off. He just keeps going and going and going, the bike a perpetual motion machine as Buster narrowly – and wholly accidentally – avoids disaster after disaster with increasing improbability. The joy of the scene comes in the way it exponentially ratchets up the danger, and the complex mechanics of the many coincidences that guide our unwitting detective to safety. The sequence’s clockwork precision and growing surreality are more reminiscent of a Looney Tunes cartoon, where everything is drawn by hand, than anything we would expect to see in live-action, where every beat must be literally staged before the camera. At a certain point, it ceases to produce actual laughter, and gives way to pure tension and astonishment. I don’t care how many times I see it, or what I know about how the moment was produced (a trick I dare not spoil here): When Buster goes past a giant oncoming train, the camera tracking parallel with Buster so the train is coming right at both the character and the viewer, I cannot help but audibly gasp. It is a truly mind-blowing stunt, a mic-drop ending to one of the greatest extended sequences of physical comedy ever captured on celluloid.

8. If you’re short, just embrace it

Tom Cruise has clearly learned a lot from Buster Keaton, but he somehow missed this lesson. Keaton was a lithe 5’5”, and he loved to exaggerate his stature for comedic effect. In Sherlock Jr., the entire sequence where he’s tailing the rival suitor is predicated on that height difference, and the geometric blocking of their mis-matched bodies within the frame is a constant delight – as is the scene just before this, where Buster first plays detective with his love interest’s family, and he’s the shortest one in the room by at least a head while trying to be commanding. Cruise is 5’7”, if reports are to be believed (and knowing Cruise, that information is suspect), and while the recent Mission: Impossible films aren’t quite as maniacal about disguising his height as some of the earlier entries, I do think the movies would benefit from just leaning in and letting Ethan Hunt be the Short King we all know he is. Keaton did it 100 years ago; there would be absolutely no shame in this now.

9. The dreamlike, phantasmal nature of our relationship to cinema

It really cannot be stressed enough how perfectly and profoundly so many decades of film theory are encapsulated in the sequence where Buster falls asleep and dreams his way into the space of the movie. The dream self is shown literally emerging from the sleeping body, a spectral presence stepping away from its physical boundaries, and then going on to literally step into the film being projected. This in and of itself is powerfully symbolic, but there is, I think, a crucial middle step here that also demands observation: the moment wherein Buster’s dream self surveys the screen and transforms the figures upon it into the people from his own life, the figures of his waking reality that are the source of his mind’s anxiety. This, of course, is what we as viewers do with movies all the time, when we identify with the film in front of us and read ourselves and our lives onto the bodies on screen.

The dream self then approaching the screen and stepping into inside it is the last step in this literalization of cinematic spectatorship and identification. There is a comedic purpose to all of this, of course, and the scenes of Buster being buffeted between various movie scenarios are quite funny; but the sequence is also extremely poignant, in how eloquently it visualizes the connection between experiencing a dream and watching a movie, and the way we ‘insert’ ourselves into films as a way of understanding our daily, waking life. Keaton spends several unbroken minutes here on a frame-within-a-frame, looking at an audience watching Buster inside the movies, even as we ourselves are, of course, an audience watching Buster inside a movie. Even if the viewer is not conscious of it, Keaton makes us acutely aware of our own viewing situation, puts us in a reflexive stance and gets us thinking about how we engage with film. 100 years on, Sherlock Jr. continues to be a marvelous and irreplaceable tool for theorizing cinema, because it takes ideas that critics and scholars around the world would spend the next century writing down, exploring through complex theoretical systems like psychoanalysis and apparatus theory and semiotics, and wordlessly expresses the underlying engine of all those ideas through the substance of film itself.

Sherlock Jr. ends with Buster looking through the projection booth’s viewing window out to the film being shown, seeking guidance on how to woo his paramour. But of course, when he looks, he gazes directly at us, quietly breaking the fourth wall to remind us that, in watching this or any other film, “we are like the dreamer, who dreams and then lives in the dream” (to quote a phrase from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad that David Lynch, cinema’s foremost expert on dreaming, is particularly fond of).

10. More movie characters should carry around books with titles pertaining to their vocational aspirations

I mean this one’s pretty self-explanatory. How wonderful is it when we are introduced to Buster’s character and see him reading a little book titled How to Be a Detective. I love that. I wish we still did that in movies. How fun would it be if Indiana Jones was reading a book called How to Be an Archeologist when he boards the plane for Nepal in Raiders of the Lost Ark? Or if Charles Foster Kane was carting around a tome titled How to Become a Newspaper Magnate? The John Wick movies really should have stolen this. How on earth is there not a scene, anywhere in those four movies, where somebody at the Continental is reading How to Be an Assassin? In retrospect, it might be the only thing missing from those movies.

NEXT WEEK: We take a trip into the world of 007 for the 45th anniversary of one of James Bond’s most celebrated adventures: ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE!

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.