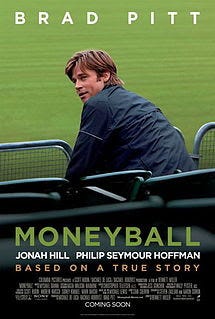

Review: Smart, powerfully-acted "Moneyball" is a rewarding look at the dark side of baseball

Film Rating: A–

I love baseball. It’s far and away my favorite sport, and the only one I follow regularly (as a fan of the Colorado Rockies, if you were wondering). Yet with its slow-paced, thoughtful nature, baseball is easily the least suitable for film among all major sports. Large chunks of hockey or football films can glide by on the visceral thrills provided by most match-ups, but baseball doesn’t have that luxury. As such, I really can’t think of a baseball movie I enjoy off the top of my head, and it’s not at all a stretch to say that Bennet Miller’s “Moneyball” is the finest film about the sport I’ve ever witnessed. Continue reading after the jump...

Like protagonist Billy Beane, Miller – along with the dynamite screenwriting duo of Aaron Sorkin and Steven Zaillian – breaks many of the established rules of his craft in order to succeed. Sports films are supposed to be about big games, startling moments of victory and inspiration; “Moneyball” doesn’t show any baseball at all until very late in the film. It ends on a note of melancholy, rather than triumph, and unlike most sports dramas, you won’t find any players or coaches at the center of attention. The main character is a General Manager – I think it’s safe to say no baseball film has done that before – and his ‘sidekick’ is a Yale graduate with an Economics degree. “Moneyball” isn’t concerned with how baseball is played or what goes on during the game, but on the behind-the-scenes action. Most unorthodox of all, perhaps, is that “Moneyball” doesn’t ever glorify the sport it depicts, but is rather very critical of the shadow the ‘business’ game casts over the actual game.

The film opens by establishing the budget disparities between rich teams, like the New York Yankees, and poor teams, such as the Oakland Athletics. At the outset, the Athletics have just lost their shot at the playoffs to the Yankees, and all of their best players have been snatched up by wealthier teams. General Manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) is faced with rebuilding on a budget of $39 million, the smallest in Major League Baseball, and is convinced that traditional methods – buying the best players possible with limited funds – simply won’t cut it. Peter Brandt (Jonah Hill playing a fictional amalgamation of multiple real-life figures) has the same idea, and has developed a complex, radical new method of analyzing player statistics. Rather than buying players, Brandt believes they need to buy runs, and buying runs means picking players with the best shot at getting on base. Players with high-salaries are typically rewarded because they are well-rounded, but they often have lower on-base percentages than undervalued players with specific skill-sets. Most importantly, Brandt is positive he can help Beane assemble a championship team with $39 million, and Beane decides to put his career and team on the line to test this new theory.

Any baseball fan can tell you that what happens off the diamond – trades, bringing rookie players up, sending others down, etc. – is often just as fascinating as the game itself, and in the case of “Moneyball,” the business side of things is the dominant force. Suffice to say, it’s absolutely riveting. Sorkin’s contributions to the script are immediately recognizable, as his snappy, efficient dialogue barrages the viewer with information while keeping us entertained. Only one game is dramatized, and the rest of the time focuses on Beane bringing in undervalued players, making trades, and most importantly, defending his radical ideas to those who disagree. Baseball enthusiasts will be captivated, and those new to the game will learn volumes about the influence managerial decisions can have.

Like Billy Beane, Sorkin and Zaillian are unafraid to ask some big questions about how baseball operates: is it fair that a team’s wealth often defines their success? If baseball is so financially motivated, how can poorer teams ever hope to succeed? Does the money undermine the game’s integrity? “Moneyball” casts a critical eye on the sport and provides no easy answers; after all, even Beane’s radical new ideas are based around money. Should his new team succeed wildly, he won’t have done away with baseball’s fixation on funding – he’ll only have proved that there are other ways to work within this system.

This is all fascinating stuff, far more engaging and lively than business discussions probably have any right to be. But the business aspect alone doesn’t give “Moneyball” a strong dramatic core. It is first and foremost a character study, an in-depth analysis of Billy Beane’s psyche. The entire film is told from his point of view, and though I’ve focused on many of the macroscopic themes about baseball, “Moneyball” is primarily the story of one man’s quest to find fulfillment in his work. The film takes its time developing this character, using a measured, focused pace to add weight to each decision he makes. Lesser filmmakers would be tempted to get caught up in the ‘inspirational’ nature of the story, but Bennet and company are more interested in the human element. Flashbacks to Beane’s past are used to explain his belief in Brandt’s theories, and the film also takes several rewarding detours to explore Beane’s family life. The result is a tremendously compelling lead character, one who makes the film as rewarding emotionally as it is intellectually.

Beane is played by Brad Pitt, one of my all-time favorite actors; his versatility is always startling, rarely giving the same performance twice, and his creation of Billy Beane is unlike anything Pitt has done before. He gets to be charming and funny, of course, but this is a role that primarily demands nuanced expression and introspectiveness, and Pitt hits it out of the park, if you’ll pardon the pun. He should absolutely be in the discussion come Oscar time.

As Peter Brandt, Jonah Hill is even more revelatory; to my knowledge, this is his first non-comedic role, and it’s startling how unrecognizable Hill is here from past performances. He’s not snarky, loud, over-the-top, or frantic, but calm, a wee bit neurotic, and introverted. Hill is fantastic and, though I love watching him in comedies, I think “Moneyball” could very easily be the start of a refocused dramatic career.

“Moneyball” is a complete, committed work, intelligently written, capably directed, and wholly free of clutter. That makes it a bit of a rarity these days. I took issue with the pacing at certain points, especially during the protracted ending, but none of this lessens the film’s impact. It works on multiple levels, and its focus on character will make it appealing even to those who have never sat through nine innings. For those of us who do follow baseball, it’s especially rewarding to see a movie that manages to capture all that is good and bad about the sport, a film that deconstructs and celebrates the complex magic of America’s favorite pastime.