Review: Takeshi Koike's "Lupin the IIIrd" Trilogy, 10 Years On

Movie of the Week #16 is an anime triple feature

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week for paid subscribers. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

Lupin the Third rejuvenated itself in more ways than one with the 2012 TV anime The Woman Called Fujiko Mine. It was the first time Lupin had returned to television as a weekly half-hour anime since the final broadcast of Lupin the Third Part III in 1985; it had a refreshed voice cast after the retirements of three of the five series leads, including for title character Fujiko Mine, now played by Miyuki Sawashiro; and it was the first installment in the franchise creatively headed by women, with Sayo Yamamoto as the series’ director and Mari Okada as the ‘series composer,’ right around the time she started breaking out as the most prolific and lauded anime writer of the era. Most importantly, it boasted a radically new and inventive aesthetic, not just for the Lupin franchise, but for television anime on the whole. Its design language, led by Takeshi Koike as character designer and animation director, went back to Monkey Punch’s original manga for inspiration, not just in the character designs – which Yamamoto directed Koike to keep close to the manga depictions – but in the fierce, fast, sketchy line work of Monkey Punch’s drawings. The anime mostly banishes inking from its vocabulary, with all the characters and most of the backgrounds sketched in with pencil, usually with a heavier tip so we can see the uneven, rough texture of the graphite. Visually, it is all incredibly striking, a bold piece of avant-garde pop that feels like a book of sketches come to life, their sense of shape-shifting anarchy fully intact.

It’s a blessing, then, that the thirteen episodes of The Woman Called Fujiko Mine weren’t all we got from this corner of the Lupin universe. While the series continued with more traditional anime on television, Takeshi Koike came back to direct what grew into a trilogy of follow-up films, released in 2014, 2017, and 2019. I say ‘films,’ but how exactly one classifies them is up for debate – they’re each in the range of 50 minutes long, and are all technically comprised of two segments with a break in the middle, so they’re really each 2-part OVAs (original video animations), though all had theatrical releases as well, and certainly boast robust-enough production values to look and move like cinema.

Whatever one calls them, Koike’s trilogy is fascinating and compelling viewing: a touch less aesthetically experimental than The Woman Called Fujiko Mine (the films remove a lot of the heavy graphite shading employed by the series, for instance, to focus more on the line work of the characters), but also several degrees darker and more violent than what could be done on TV, making these some of the most unique and unusual entries in Lupin the Third’s long anime history. The films even give themselves a unique title treatment, spelling the series’ name as Lupin the IIIrd, to make it clear that these films stand apart from the rest of their franchise. Throughout, Koike’s astonishing aptitude for motion and impact is displayed in full force, along with a masterful command of tone and atmosphere. Each of the three films focuses on a different member of the 5-person Lupin cast, but each also tries on a different genre and set of archetypes, giving viewers a tour of the kinds of pulp narrative forms Lupin and its characters draw from. There’s a sense of the outlandish anarchy inherited from Monkey Punch’s original manga, but with a modernist edge that is entirely this trilogy’s own.

Koike’s first film, Jigen’s Gravestone, celebrates its tenth anniversary this year. It is a lean and mean ‘Jigen takes on a big bad assassin’ story, which Lupin the Third has done dozens of times across various episodes and specials. Jigen’s Gravestone isn’t the absolute best of those (there’s a lot of competition!), but with Koike’s amazing and singular animation, particular his slick and impactful sense of movement, this is definitely one of the most viscerally satisfying.

The plot and setting here are in line with the Cold War political landscape of The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, (and a lot of 20th century Lupin stories), but it’s less engaged with history and politics than the TV series was; here, it’s all mainly an excuse to put Jigen and Lupin up against a colorful assassin, give us a lot of incredibly crunchy and detailed gun animations – if you, like me, find that one of your chief pleasures watching Lupin the Third is seeing obsessively intricate drawings of guns being maintained, drawn, fired, and reloaded, this one’s got you covered – and build to an absolutely dynamite final shoot-out that is pitch-perfect in its precise, gentlemanly brutality. If you can get through the bloody climax without gasping, you have a stronger constitution than me.

Kanichi Kurita and Kiyoshi Kobayashi have established such great chemistry at this point, and even though they’re technically playing younger versions of Lupin and Jigen who aren’t yet lifelong friends and accomplices, you feel the weight of it all in their scenes together. Old-man Kobayashi’s Jigen is maybe my favorite flavor of the character; it makes no logical in-universe sense for Jigen to have the voice of an 80-year-old (unless all those cigarettes have really done a number on his vocal chords), but it feels absolutely right that Daisuke Jigen, who like many of the Lupin cast members is a fundamental anachronism, and more than any of them is an old soul at heart, would wear a lot of miles in the way he talks. Kobayashi’s voice aged like fine wine – the older it got, the more compelling he became. Jigen’s Gravestone is, if nothing else, a sterling testament to his legendary performance.

The second film, Goemon’s Blood Spray, could also be called How Goemon Got His Groove Back (by Dismembering Lots of People), though the actual title is a bit more to the point. Either way, this is far and away the most violent and visceral Lupin the Third entry I’ve ever seen (and I can’t imagine there’s anything out there to challenge it), making good on the promise of its title and even giving every member of the gang (minus Fujiko) a grisly injury or two along the way. It definitely verges on veering too far away from a recognizable Lupin the Third story at times because of that violence quotient – and I definitely don’t like the darker, crueler depiction of Zenigata, either here or in The Woman Called Fujiko Mine (my only real complaint with that show) – but overall, I think it works, and it works because this is a Goemon story, and Goemon has always been the least rigidly ‘defined’ member of the Lupin troupe, meaning you can bend him the farthest without the show around him breaking.

Don’t get me wrong, I love Goemon – but he’s generally the member of the gang who has the least to do outside the big moments where he saves everyone with swordplay (usually by cutting a car, helicopter, tank, or other piece of heavy machinery in half) and the series in all its incarnations has generally struggled to tell great stand-alone Goemon-centric stories the way they’ve always been able to do with Jigen or Zenigata (or Fujiko, depending on the era).

Here, Takeshi Koike and company solve that problem by putting Goemon straight into a modern-day Samurai drama (by way of a Yakuza picture, though the genres always had some overlap), and let the style flow naturally from there. The film’s hyper-violence is in line with the many samurai and yakuza pictures made in the wake of the iconic climax of Akira Kurosawa’s Sanjuro (which opened the floodgates for just how much blood could come from a single sword fight), or with series like Lone Wolf and Cub (the original manga of which was published in Weekly Manga Action alongside Monkey Punch’s Lupin the Third stories). What happens to Goemon and his opponent in the final confrontation is genuinely one of the gnarliest, most shocking displays of violence I’ve ever seen on screen, and its impact definitely lingers. Goemon doesn’t walk out of this anything close to unscathed, but neither does the viewer.

That said, the film is also extraordinarily beautiful at times. The background art is just exquisite, particularly at the end during the final show-down at the Buddhist temple, where the skies are drawn with inky black watercolors like an ancient wall scroll. And of course, the action is exquisite – incredibly fluid and fierce, flowing like water, making you gasp and move to the edge of your seat. It is simultaneously elegant and brutal, an intoxicating combination.

It helps that, amidst this samurai story, they’ve given Goemon a decidedly unexpected opponent. Hawk, a big blonde lumberjack, is not at all what you’d normally see from a samurai movie big bad, and his unconventional, heavy axe fighting makes for a great, surprising contrast with Goemon’s fluid balletic motion. He’s a great character, and the most Monkey Punch touch of the film – a crazy invention plopped in the middle of an otherwise recognizable narrative shape.

As with Jigen in his Koike film, I don’t know if this is Goemon’s absolute finest hour in the Lupinfranchise – there’s the infamous torture episode from Part II, which I love, and his original appearance as Lupin’s enemy in Part I, and my overall favorite depiction of him might be his episodes of The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, where he really benefits from that show’s episodic focus on individual characters encountering Fujiko – but it’s definitely up there. And good god, is it violent.

The third film, Fujiko’s Lie, is easily my favorite of the bunch. It just brims with confidence and atmosphere and a commanding sense of tone, hitting the absolute perfect sweet-spot where it functions as a darker, grittier take on these characters without ever feeling divorced from the larger world and legacy of Lupin. It’s gorgeously animated, even more so than the last two films – the backgrounds are just jaw-dropping start to finish – and Fujiko’s big fight with Bincam at the end is, in its own way, just as impressively fluid and impactful as anything in Goemon’s Blood Spray.

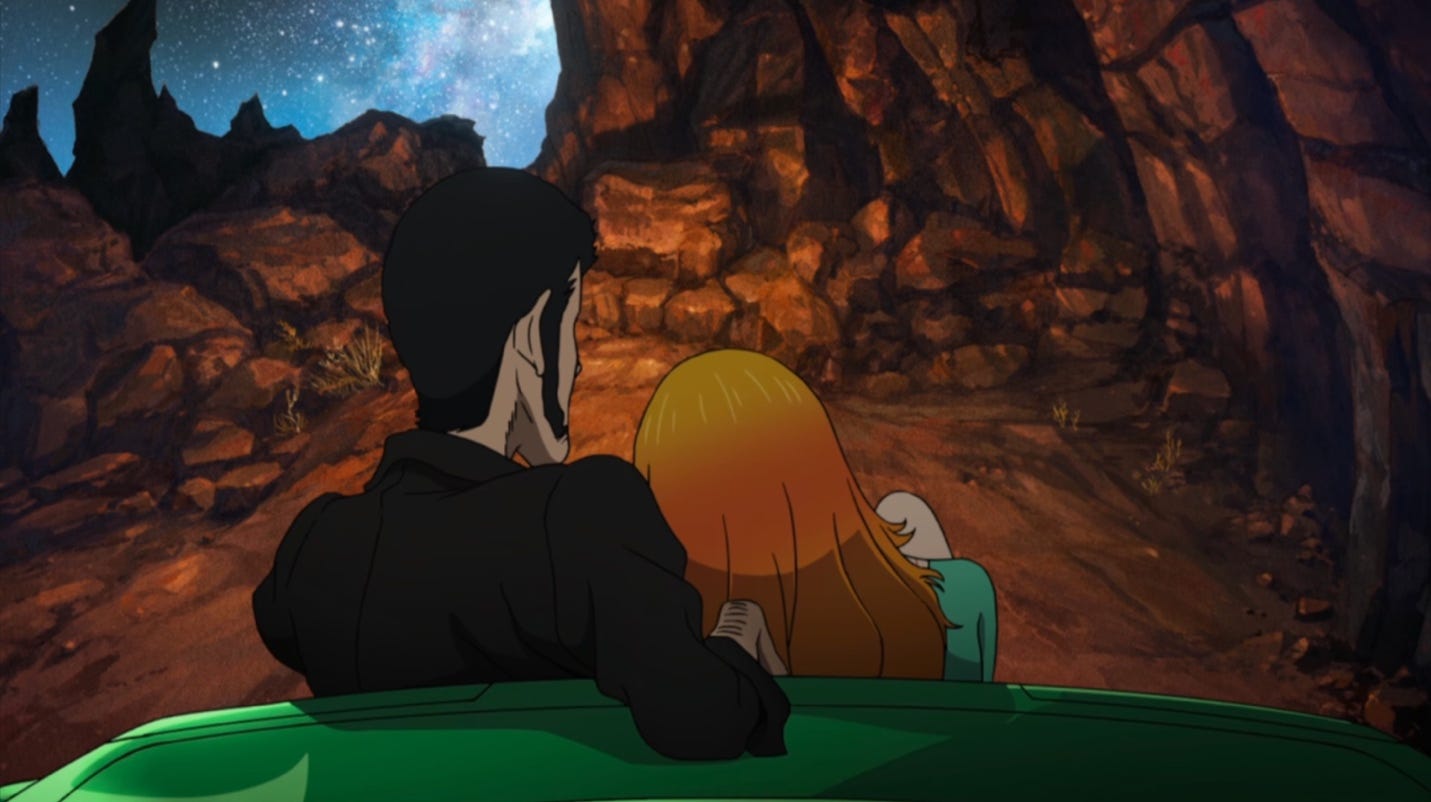

But what works best here is the story, which is absolutely rock solid. Here, Koike’s film benefits enormously from the foundation laid by Mari Okada and Sayo Yamamoto on The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, which gave the franchise its best and most compelling take on Fujiko to date. Fujiko’s Lie effectively recaptures how well that anime used her, telling a story where it is impossible to tell how sincere Fujiko is at any given time – whether she’s purely out for selfish gains, or has a heart beating around in there somewhere after all. But we never know for sure, because Fujiko plays things so close to the vest that she never truly lets anyone in, and that includes the audience. So the story winds up being one where we are given some concrete facts at the end, but are ultimately left to speculate as to where Fujiko’s head is at. Miyuki Sawashiro is as phenomenal as ever here, and the final scene between her and Kanichi Kurita as Lupin, looking up at the stars together out in the desert, is one of the finest and most evocative vocal duets in the entire world of Lupin the Third.

Fujiko’s Lie is among the best pieces of Lupin media, and if you count it as a feature film (this one pushes right up to the line of a full hour, so it’s pretty close), it is the best Lupin movie made since Miyazaki’s Castle of Cagliostro. We are five years out from the release of Fujiko’s Lie, and a decade from the beginning of Koike’s Lupin the IIIrd series in 2014, but I desperately hope there is more to come. Not only because there are still leftover plot threads to tie together – I might willingly suffer the injury Goemon endures at the end of his film for the chance to see what this team was planning to do with Mamo, villain of the very first Lupin movie who cameos near the end of Jigen’s Gravestone – but because this trilogy is such a special and stunningly produced take on the Lupin universe, one that only gets better with each subsequent entry. I want more of it, badly. There’s a reason I’m putting this piece out the week of Thanksgiving; these are three movies I am quite thankful for, indeed.

NEXT WEEK: We have fun with the cult comedy classic TOP SECRET, the Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker send-up of Elvis flicks, WWII movies, and much more, celebrating its 40th anniversary this year!

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.