Review: “The Holdovers” is the best film of 1970, and maybe of 2023

Alexander Payne has given us one hell of a Christmas present

I love this movie like it’s a person.

I love it from the most basic layer of shape and texture – literally. I got a chill down my spine when the lights went out and the theater adjusted its masking to my favorite aspect ratio, 1.66:1, and then another when the film began with a classic MPAA rating card and 1970s-style logos for the production companies. Then comes the texture of the images themselves. Alexander Payne apparently found himself a time machine and got 35mm stock from the early 1970s, so completely does this film capture the grain structure and color depth and halation patterns of film from that time. The whole movie is presented like it’s a print, not ostentatiously or in your face like Grindhouse with its scratches and missing reels, but with some marks and imperfections left intact, like we’re seeing the print opening weekend after it’s been screened a few times. The movie feels alive, in that particular way celluloid asserts a life all its own. The images it captures are of production design that is absolutely miraculous in its unassuming verisimilitude – real spaces seemingly pulled straight from memories, every detail intact. There is a scene at a Christmas party in a house in the suburbs where two young people go downstairs to see all the children cloistered together away from the adults, making art with glue and popsicle sticks; I felt like the projector had somehow tapped into my brain and started broadcasting recollections of family gatherings from years ago.

The details are everything, because Payne’s story – written by screenwriter David Hemingson – is simple and archetypal. You have seen the broad strokes before: A cranky older man, in this case a teacher; a promising but behaviorally delinquent young student; a mother mourning the loss of a son. Three misfits and loners, made that way by choice or by circumstance, thrust into each other’s orbit over the holidays at an east coast boarding school. Over the course of the film, they gradually learn about each other, see their pain and their joys reflected and refracted in the other’s eyes, and thus learn about themselves. At the end they have all changed a little bit, enough to make an important decision they could not make before.

These basic descriptions could serve any number of movies, but The Holdovers is singular. In its boundless love for its characters, and the pervasive empathy used to illustrate their world; in its engagement with the prickly realities of class, and the indignities many of us are wrongly taught to view as invisible; in the ways it understands people as unique amalgams of myriad contradictions, flaws, and virtues, and thus renders even the most fleeting of characters fully three dimensional and human; in its humor and its wordplay and its sharp, incisive wit; in its gentleness and its open heart, there are very few movies like The Holdovers.

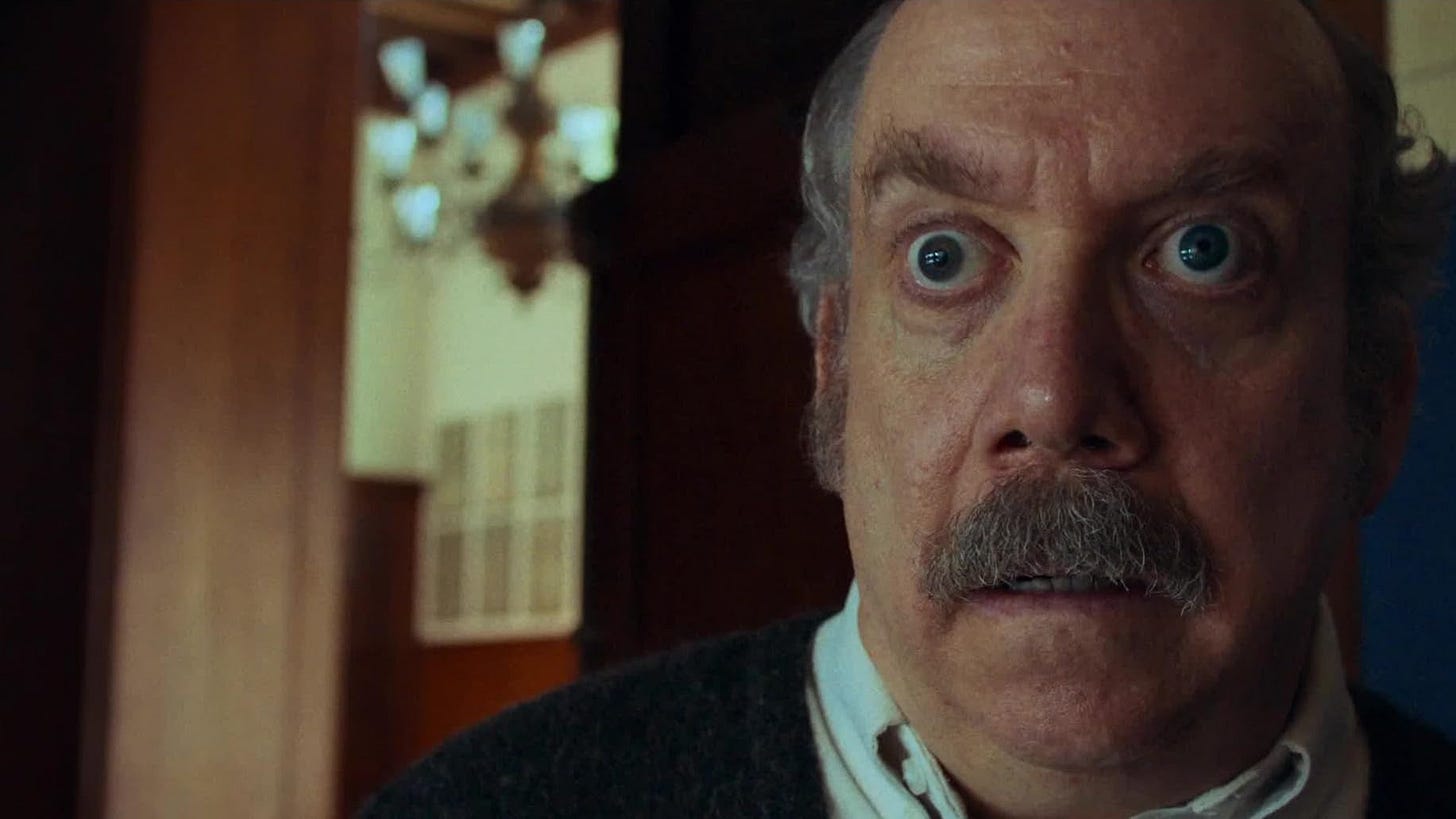

Paul Giamatti reunites with Alexander Payne here twenty years after the most iconic film of both their careers – 2004’s Sideways – and gives the performance of a lifetime as Paul Hunham, a teacher of ancient history whose greatest joy seems to come from expressing disappointment in others. Giamatti’s work is astonishing. I’ve known men like this. He reminds me of a Shakespeare professor I had my second year of college. That man too was cranky and short-tempered; his entire world appeared to be his subject matter, and he spoke exclusively in references to his own expertise. When a student complained about being able to make it to class on time in the winter, he told them to buy a bike and learn to ride it through the snow. He was harsh and challenging and always cut to the quick, and he was eminently, perhaps uncomfortably, fair. I was not sure if I liked him or his course in the moment, but ten years on, I think about what I learned in his classroom a lot. As a teacher, I often find myself wanting to repeat his words to my students; the older I get, the more I probably will. Giamatti’s character is that kind of person, capture perfectly. What he has accomplished isn’t so much a performance as a spiritual channeling of a real human being, complete and complex in all the dimensions in which we exist.

This is true too of the other lead performances. As Giamatti’s main foil, newcomer Dominic Sessa plays Angus, a smart but troublesome student abandoned at the holidays, and it is one of the most immediate, unmannered, and charming teenage performances I have ever seen on screen. It is no small feat to share the screen opposite Paul Giamatti for over two hours, but Sessa consistently gives as good as he gets; it is a real duet, and a beautiful one. Da’Vine Joy Randolph rounds out the central trio as Mary, the cafeteria administrator left to cook for the few students remaining over the holidays; she is also grieving the death of her son Curtis in Vietnam, the first and so far only Barton Academy alumni to die in that war, because unlike the rich and powerful people whose children populate most of Barton, this family could not afford college or the resulting deferment. For all his grumpiness, we can tell Paul is of a more substantive character than most of the people around him because he insists on treating Mary with dignity and empathy, especially when his entitled students will not; in return he makes one of his few friends. Randolph is remarkable in the role, conveying a complete spectrum of human experience whenever she is on screen, making this character feel vibrant and alive and more than a single emotion or idea at all times. There is a scene where Mary sorts through Curtis’ baby clothes at her sister’s house; it is quiet and simple and utterly free of histrionics or cloying sentiment, and in its small quotidian observation it is absolutely devastating.

The Holdovers is in fact the kind of movie where I spent the entire running time either laughing – this is a tremendously funny film – or finding myself on the verge of tears. Not because anything sad or even particularly emotional is going on in every scene, necessarily, but because every minute of it feels so real, so human. I see so much of myself and my life and the lives of people I’ve known in the film’s images and performances and dialogue. I found so much love and empathy and understanding for people and for parts of myself that have felt misunderstood or unloved. By the time the end credits rolled, I understood myself a little bit better than I did when the opening credits started. This is what great art is capable of, and watching The Holdovers feels like discovering that truth again anew.

I love this movie. It is one of my new favorites – and easily one of the greatest Christmas movies, a film that understands the season less as a collection of rituals and iconography than as a complex, challenging, and ultimately rewarding emotional playing field, a space wherein the weight of time and experience collapses upon people and reshapes them from the inside out. It is a film that styles itself after the early 1970s not only because that’s the period setting, but because it is the kind of finely-observed, precisely-authored human drama Hollywood once briefly thrived on; were it actually released in 1970, the year it is set, it would easily be one of, if not the, best American films of that year. As for 2023, there are several weeks and many more movies to go, and it has already been an extraordinary year for the art of cinema; but as of this writing, The Holdovers is my favorite film of the year. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

If you liked this review, I have 200 more for you – read my new book, 200 Reviews, in Paperback and on Kindle: https://a.co/d/bivNN0e

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our podcast about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com