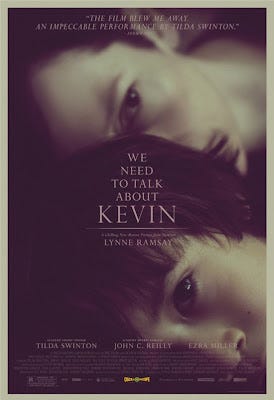

Review: "We Need to Talk About Kevin" is a profoundly unsettling work of art

Film Rating: A

This review was originally published on November 11th, 2011 as part of my Starz Denver Film Festival coverage, and the film was later listed as the 15th best film of the year on my Top Twenty Films of 2011. The review is reprinted here to mark the film's Denver release at the Landmark Esquire. I obviously recommend the film quite highly.

I have a feeling that “We Need to Talk About Kevin” is going to resonate very powerfully with audiences in and around Denver, particularly those who lived here during the Columbine High School massacre of 1999. I was six at the time, but I remember it clearly; it was the same week my Grandfather died, and his passing was only one small part of the larger, inescapable sense of communal grief enveloping Colorado. The anguish of the killings has never really abated, influencing so many corners of our local society. I’ve grown up in a reactive school system, one oppressively sensitive to anything that directly or, more often, indirectly echoes Columbine, where every conversation we had about teenage violence or misbehavior inevitably worked its way back to April 20, 1999. For adults, Columbine has come to represent the unbridled fear of losing a child at a place that should be safe; for kids, Columbine forever altered the way we are educated and treated. It all comes from a place of immeasurable grief brought on by an act of unspeakable evil, an event I’ve been close to for twelve years and still can’t come close to comprehending.

“We Need to Talk About Kevin” explores the epicenter of a Columbine-esque tragedy: the parent. Trust me when I say that no conversation about Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold ever goes by without mention of their parents, questioning how anyone could be so unaware of their child’s nature. This is the enigma “Kevin” tackles, and it does so spectacularly, planting the viewer firmly into the mind of a killer’s mother and keeping us there for two straight hours. It is a relentlessly dark and uncomfortable experience, but also a profoundly rewarding one. The mother is never absolved, but we gain a keen understanding and sympathy. How could we not? The key question the film asks is one that should strike fear into the hearts of all viewers: what would you do if you didn’t love you child, if you hated them on instinct and they hated you right back?

I can think of few topics more horrifying, and the film is proportionally unsettling. Continue reading after the jump...

Tilda Swinton stars as Eva Khatchadourian (that’s the last time I’ll be typing out that name); in the present, Eva is a pariah. She wakes up one morning to find her house splattered in red paint; when she goes out in public, she attracts nothing but hateful stares and, on occasion, violent confrontations. As she wanders aimlessly through life, trying her best to recoup some semblance of normality, she thinks about her past. It’s all she can think about. Her story is traced back all the way to the moment when she met the father of her son Kevin, and from there, most of the film focuses on the child’s upbringing.

As co-writer/Director Lynne Ramsey and co-writer Rory Kinnear noted in a Q&A at the screening I attended, viewers often discuss whether it was nature or nurture that made Kevin commit his terrible crime. These viewers have completely missed the point. “Kevin” isn’t about nature versus nurture, but the point at which nature and nurture intersect. Kevin clearly has problems, displaying psychopathic tendencies from an early age. No amount of motherly love could heal Kevin’s psyche; it’s just the way he was born. But he didn’t have to act on psychosis the way he did, and that’s where nurture plays its part.

Eva, a free-spirited bohemian, never wanted to be a mother. It was clear to me early on that it would have been difficult for her to embrace any child as her own; even the most ideal youngster would represent the dreams Eva had to give up, all the travelling and adventures she will never get to experience. She approaches motherhood not with enthusiasm, but with hesitancy bordering on panic. When the boy is born, she realizes that the motherly bond society says she should have simply isn’t there. When Kevin learns to talk and begins tormenting his mother, she recognizes his underlying nature right away. Her husband (John C. Reilly doing excellent work) only sees the good in Kevin (or, more accurately, the good Kevin wants him to see) because he doesn’t come from a place of apprehension; he is ready and willing to love. Eva is not, and as such, her relationship with Kevin is frank and destructive.

To me, the most important question of the movie is where Kevin and Eva’s mutual hatred stems from. It’s a chicken-and-the-egg situation: Did Kevin hate his mother first, leading her to detest him in return, or was it the other way around? Kevin is the first to show outward hostility, tormenting his mother like a young Hannibal Lecter from an early age; but Eva never wanted him to begin with, and her reaction to Kevin’s constant, unending crying as a baby could be construed as hatred. Did Kevin pick up on these negative emotions as he matured? Or did Eva really try to open herself to motherhood, with Kevin’s hatred manifesting itself internally? Did Eva’s relationship with her son contribute to Kevin’s violent, life-shattering outburst? There are no easy answers. I believe the truth lies in a combination of every theory one might posit; this is delicate, complex territory, and it is illustrated with harsh precision.

Indeed, “We Need to Talk About Kevin” is a superbly crafted film, utilizing a style that accentuates the dark, beating heart of the material. Ramsey modulates between the past and present without traditional signifiers, instead moving, for the first act at least, with a stream-of-consciousness momentum that puts us squarely inside Eva’s mind. Information is parsed out slowly; for a long time we have no idea just who Eva is or how her many divergent flashbacks are related. Like her psyche, the narrative is initially fragmented; once she begins making sense of her past, the film does as well. We aren’t told the details of Kevin’s atrocities until the very end, but Eva’s isolation and guilt are so thoroughly established that we understand on an instinctive and emotional level the weight each flashback carries.

The cinematography is an important part of the storytelling, with Ramsey showing a terrific mastery of the frame and implementing clear, fluid photography at all times. Her use of color, specifically the color red, is particularly fascinating; it serves as the film’s primary visual motif. I didn’t keep count, but I don’t think a single shot goes by without some immediately recognizable source of red in the frame. The symbolism is obvious, but it’s the degree to which Ramsey uses red in each shot that helps tell the story, even on a subconscious level. Eva’s present and the earliest-shown moment of her past are overflowing with dark, thick reds; in between, the color gradually grows in significance. Were one to recut the film chronologically, the amount of red in the frame would gradually expand until it becomes all consuming, just as the ramifications of Eva’s small, seemingly insignificant act of sex with a stranger rapidly grows more and more monstrous, careening towards a devastating outcome.

But Ramsey’s greatest tool is her cast. Tilda Swinton has long since established herself as one of the best actresses in the business for complex, unflinching work, and as Eva, she turns in the greatest performance of her career. Her dialogue is extremely limited – Ramsey compared it to silent film acting – but Swinton doesn’t need any; in the present-day scenes, her haunted facial features express the terrible fathoms of her past; as she raises Kevin, she perfectly illustrates Eva’s fear, disgust, and desperation. Through Swinton, we understand and sympathize with this character, even if we rarely condone her choices or parenting style; that’s an incredibly tough balancing act, but Swinton never makes it look hard. I was most impressed with the scenes where she tries to engage Kevin as a loving mother, demonstrating the full depths of Eva’s desperation and despair.

Kevin himself is portrayed by two young actors; Jasper Newell plays the six-to-eight year old Kevin, and is quite good. I wonder if the boy is a bit too precocious at times, even for a budding psychopath, but nevertheless, this is remarkably accomplished work for a child to deliver, also speaking to Ramsey’s talent as a director. It’s when Ezra Miller enters as teenage Kevin, though, that the film moves into full-blown psychological horror territory. Miller is terrific, disturbing and unsettling but also nuanced; Ramsey described him as being “magnetic and repllent at the same time.” If young Kevin feels like a well-staged creation, Miller’s Kevin is a fully realized human being. He doesn’t operate on just one level, and despite the character’s cool, collected nature, Miller manages to suggest vulnerability. To me, this made the character so much scarier, to watch someone recognizably human embrace evil so completely. I don’t think we ever sympathize with Kevin, or even understand him, but he is tangible in a way villains seldom are, making the film that much more emotionally complex.

“We Need to Talk About Kevin” is not a film I would recommend for the weak-of-heart. It is an intense, at times unbearably distressing movie, asking big questions most would rather never ponder and offering no easy answers. This is what makes the film great, but at the same time, it is a movie I never wish to see again; it explores a dark side of humanity I can only be enveloped in for so long. Those with children will undoubtedly be far more affected than I, and in Colorado, the subject matter could simply be too close to people’s hearts. I recommend it as an incredibly accomplished work of art, but not as a film general audiences should immediately seek out.