Reviews: "The Terminator" and "Terminator 2" form James Cameron's Perfect Duology

Movie of the Week #14 celebrates a franchise turning 40

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column for paid subscribers where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week for paid subscribers. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

James Cameron’s The Terminator turns 40 this week, having originally opened in American theaters on October 26th, 1984. It was not, technically, Cameron’s directorial debut (that would be 1982’s Piranha II: The Spawning), but there is a reason The Terminator is generally remembered as the movie that launched one of the most successful and influential directorial careers in Hollywood history. Yet for a film that has left an indelible mark on popular culture, and on filmmaking in general, it still amazes me, every time I revisit the film, just how thoroughly homemade the original Terminator feels - and I mean that in the best way possible.

This is not the big-budget studio action epic Cameron would later come to perfect, but a low-budget independent horror flick, featuring a simple story, a small cast, and a whole lot of creative ingenuity. It is decidedly imperfect, but imbued in every frame with a raw, relentless passion for craft and creativity, and that is what I love about it so much. There is no sense at any point that the film is holding itself back because of its limited resources; the very first shots are a series of big, ambitious special effects images illustrating a terrifying future battlefield, and throughout, the film takes big swings that it always finds a way to always follow through on, even if just by the skin of its teeth, never afraid to let you see the effort underneath. When Arnold Schwarzenegger is replaced by an animatronic for the series of shots where the Terminator removes his organic eyeball, the film isn’t expecting anyone to be fooled by the switcheroo – it’s simply the solution they found to do the scene, and the scene matters because that graphic surgery the Terminator does so coldly and clinically on himself goes so far in selling the robotic terror of what lies underneath. Cameron and Stan Winston and the team around them found a way to sell that idea, and even if it is an ‘obvious’ effect, it is still a very good and effective one, reveling in the act of creation and inviting the viewer to awe at the creative achievement.

All that effort is going towards such a solid, expertly paced little story, one that suggests a vast science-fiction mythology – one that has still, by and large, somehow gone unexplored by the parade of terrible Cameron-less sequels, which have mostly refigured Terminator 2 rather than taken any of the other interesting narrative paths opened here – but is in itself a simple, focused, character-driven slasher movie. You can see the influence of John Carpenter’s Halloween, which inspired Cameron to try making his own low-budget horror project, but you can also see many of the same influences that Carpenter was working from, including classic monster movies; Schwarzenegger’s T-800 is, in essence, a high-tech version of a Universal monster, only a few degrees removed from Boris Karloff in Frankenstein.

Schwarzenegger himself is excellent here, a remarkable physical presence of real terror and quiet intimidation, but his finest hour as the T-800 would come later. Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn are the real stars, and they are both extraordinary. The way Biehn’s performance in particular goes from broad and loud to entirely ground-level and intimate is astonishing, and there is some truly touching material near the end, some of the most evocative human storytelling Cameron has ever achieved. There is a real earnestness to this material, something that’s always been present in Cameron’s work but is perhaps felt more palpably when the material is operating at such a smaller scale. The Terminator is, ultimately, a very simple love story, one that operates on something approaching fairy tale logic, as Kyle and Sarah are drawn together by a love-at-first-sight extending across time itself. It shouldn’t work as well as it does, especially married to the film’s monster-movie slasher sensibilities, but Cameron and the cast’s passion for the material is, as with the film’s sense of visual invention, overpowering. It makes everything work, and it works rather beautifully.

Where I have always loved The Terminator, and loved it loudly and proudly, some childish, contrarian part of me has always wanted to discount Terminator 2, to take the less-popular position that the sequel, while good, isn’t actually as special as the original. Revisiting it now, that half-formed take feels needlessly iconoclastic. Judgment Day really is that great, really is one of the finest film sequels ever made, and that’s because Cameron, perhaps uniquely among all living filmmakers, understands that the potential of a sequel isn’t as a limiting space to color within pre-established lines, but an amazing opportunity to take existing pieces and assemble a new, exciting, unexpected shape. All of his sequels, from Aliens to Avatar: The Way of Water, in some way zig where you expect them to zag, and T2 may do this better than any of them.

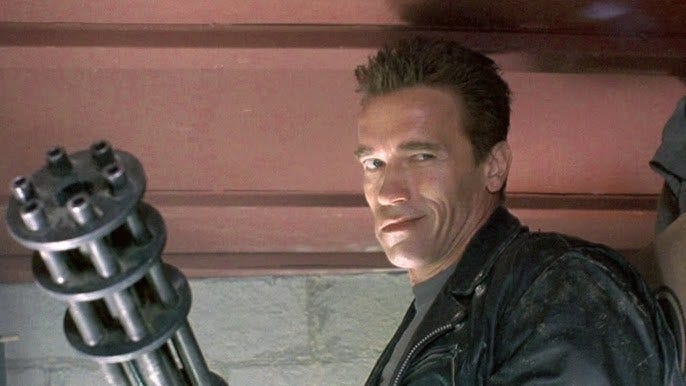

Just look at the first act of this film, and how Cameron lulls us into a false sense of security by kicking things off akin to the other sequels of the era – e.g. Home Alone 2 or Die Hard 2 – that simply reconstitute the original in a new location. T2 opens with a scene in the future re-creating shots from the original film with better effects (and they do indeed look amazing – the Terminator exoskeletons are incredible), then has Schwarzenegger arrive in the present-day naked and looking for clothes, then jumps to a smaller, more ‘normal’ person arriving. But even before the big reveal at the mall, where we definitively learn the T-800 is on John’s side and Robert Patrick is playing an advanced enemy machine, the audience can feel something is off. Schwarzenegger’s Terminator, while not yet the semi-pacifist John will later turn him into, isn’t just indiscriminately killing yet, and is more playful than he is in the equivalent scene in the original – but the other guy, dressed as a police officer, is executing with military precision. I love watching how a movie ‘plays its audience,’ and if you go into T2 studying how Cameron doles out information to first-time viewers, it’s masterful. Even John and Sarah aren’t where we expect them to be – John is in foster care living in the suburbs, and Sarah has taken Kyle Reese’s place as the raving prophet, institutionalized for her terrifying foresight. The film sets up an extremely interesting set of circumstances to extend the story in new, exciting directions, before we even get the full realization that Cameron has flipped the script entirely and made Schwarzenegger the hero.

Which, frankly, is a more natural role for him anyway. This is probably the best performance of Schwarzenegger’s career, warm and funny and profoundly moving while retaining all the singular physicality he brought to the first film. But the ultimate strength of his performance is how much energy he gets out of Edward Furlong, what a good and generous scene partner he is to this awkward, slightly cocky, mostly unmannered teenager. John Conner is a real triumph of a character, in ways I really did not understand as a kid. Watching the film with an adult’s eyes, it’s striking to me how much Cameron wants John to just be a kid in this movie, not the mythical future resistance leader. So much of the film is spent watching him process the crazy story of these movies, like the scene in Mexico where he’s under the car with the T-800, talking about how, because of the crazy time travel mechanics of his birth, he never knew his father, but will meet him as a younger man much later. Cameron approaches it with a sense of naturalism, trying to capture how a regular, present-day teen would react to these absurd, fantastical situations. What he gets out of Furlong in T2 is the exact kind of performance George Lucas needed from Jake Lloyd in The Phantom Menace but, either because of a casting mistake or his own limitations as a director, did not get: the ability to plop a naturalistic, believable child actor into the fantastical, and ground the whole thing in a very immediate sense of reality. What the characters are fighting for, ultimately, is John’s childhood, the ability for him to continue being this kid instead of a beleaguered military leader, and it’s what makes the ending so powerful – because Arnold’s Terminator ‘loves’ this kid enough, in his own mechanical way, to die for his continued adolescence.

After all, that carefree innocence is exactly what was killed in Sarah in the first movie, what died alongside Kyle Reese. Like John in T2, she really is a kid in that first movie, a slightly older teenager than John is here, but a teenager nevertheless, an awkward and unsure person gradually coming into herself, and illustrating that is one of the strengths of Linda Hamilton’s performance. The jump from there to here is truly striking. It’s not just the physical transformation, which is obviously huge, but the way she holds herself, the way she talks, the guarded-bordering-on-feral way she moves through this world. Hamilton fills in the gaps between these two movies perfectly, telling us the full story of what Sarah has been through in her performance.

While T2 is a higher-budget, more ‘professionalized’ production than the first film, that infectious energy to create is still there, as it has been throughout Cameron’s career. Still, T2 is particularly virtuosic, something that’s easy to take for granted when Cameron throws out all-time great action beats and sequences with such casual flair. The big truck vs motorcycle chase in the concrete riverbed and the group’s escape from the mental hospital are just incredible, would easily be the marquee sequence of any other action movie, but in T2, it’s just the film revving up. Over and over again we get amazing action beats that are character driven and smart and kinetic, and as in the first film, any technical challenge is gleefully overcome, Cameron and company pushing through it even if it takes massive innovation, as this film requires with the T-1000. I love how many tools are used to bring him to life, from cutting-edge CGI that still looks haunting today, to something as simple as a big chunk of molded plaster on his chest to illustrate his metal injuries. And the best special effect, of course, is Robert Patrick himself; he’s closer to the ‘anonymous’ Terminator Cameron originally conceived before casting Schwarzenegger in the first film, and he’s frankly an even scarier villain here than Arnold was last time around.

Part of why Cameron is the master of VFX filmmaking is that it never feels like he’s trying to show off – he’s just coming up with big ideas that require big solutions, and then orchestrating a lot of creativity to get there, and it’s always fun to see how that works. My favorite in T2 is a scene exclusive to the Special Edition – which is, on the whole, the better cut of the film – where John and Sarah do surgery on the Terminator to remove his chip, and it’s completely ‘D.I.Y.’ Schwarzenegger sits across from a double, the camera carefully positioned to show us no more (and no less) than we need to see, and we get the illusion of the Terminator’s brain being tinkered with in a mirror. And it’s more than just an impressive bit of cinematic problem solving; the moment is narratively crucial because of the subsequent beat where Sarah tries to destroy the Terminator’s chip, and John saves his robot buddy’s life. It is the first time John really asserts himself in the presence of his mother, the first time she really sees him as an autonomous person with his own sense of ethics, and for it to happen, the Terminator has to be disabled and momentarily out of the picture.

Speaking of ethics, there is a moral clarity to this film I find really striking today. I love how seriously Cameron takes John’s instinctual rejection of killing; it isn’t a position John can ever really articulate, and there are parts of the film where it absolutely makes everyone’s job harder, but as a kid, it’s something he just ‘gets.’ Killing is wrong. On some level it is naïve, but the movie consistently rewards his point of view, not just in how John’s ‘no killing’ mandate makes the Terminator more human, but in how it redeems his mother, and maybe even humanity.

This is the crucial turn the film takes in its second half. Sarah could easily shoot Miles Dyson, the creator of Skynet, and go home, but as we come to learn, it probably wouldn’t change anything. For one, Miles is straightforwardly a good guy, a man who loves his family and refuses to neglect them even amidst his obsessions, and who is working on the project that will become Skynet out of a sincere desire to do good with the technology. That doesn’t excuse Miles from the impact of what he has done – part of the film’s moral clarity is having Miles work as hard as the heroes, and sacrifice more than any of them, to fix his mistakes – but it complicates the idea of individual agency in the face of world-ending problems.

Miles is, after all, part of a company, part of a much bigger system in which he is just a single cog, and that system can always get someone else to come in and do his work. It is only through John’s childlike concern for his mother’s soul that the group comes to understand all this, comes to realize the actual kinds of actions that are needed to change the future. There is a sort of systemic thinking on display in Cameron’s script, an acknowledgment that changing the course of history isn’t as simple as killing one man – that the root of bad outcomes is not one person with ill intent. There is something quietly radical about a big iconic Hollywood blockbuster that rejects killing in all its forms, rejects its protagonists gunning down the ‘bad guys,’ in favor of a finale that is basically anti-corporate terrorism, with John, Sarah, Miles, and the Terminator taking down a big hub of America’s military industrial complex to prevent the apocalypse. The film’s climax is the heroes fighting a building, fighting the infrastructure of militarized capitalism, before then taking on a literally faceless enemy in the T-1000, who is doubly symbolic as both a formless blob of liquid metal capable of taking any shape, and in his chosen default appearance as a cop, an agent of the state and its monopoly on violence. And I will not lie: The image of Schwarzenegger’s Terminator, this being of near-infinite power, showing all the cops outside the Cyberdyne building more mercy – more judicious, measured use of force – than cops in our world – the cops the T-1000 takes his image from – would ever give to someone weaker than them is, in 2023, some extremely powerful and provocative imagery.

The final act in the forge is perhaps the movie’s most masterful stretch of filmmaking, this virtuosic blend of action and horror, slow and methodical and absolutely gripping. There’s a reason every single Terminator sequel has repeated the dynamic of an underpowered Terminator – usually Arnold – going up against a higher-tech, even more futuristic opponent, and getting absolutely fucking decimated along the way. It is an especially over-the-top version of the ‘action hero scraping by on his last leg’ trope – only for Schwarzenegger’s T-800, he’s literally missing limbs and most of his face. But of course, none of those sequels can successfully recapture what Cameron conjures here; none of them have this delicate sense of terror, none of them have a setting this visually arresting, and none of them end with Arnold lowering himself down into the molten steel while giving a thumbs up.

In fact, it is crazy – bordering on offensive – how many times Hollywood has tried continuing the Terminator franchise, when it ended so definitively here. How many film series, of any length, get to say they reached a truly perfect conclusion? Terminator is one of the precious few, a two-film tour-de-force that ends with its best foot forward, and feels like it left nothing on the field. What follows, after Cameron departed to raise the Titanic and travel to Pandora, is a whole series of movies premised on the idea of negating the worth of the film that made it a franchise in the first place – because to continue Terminator after T2, you have to ignore that T2 happened, or at least pretend it didn’t matter. And that is a more baffling paradox than any time travel shenanigan Cameron could ever envision.

NEXT WEEK: I consider MOBILE SUIT GUNDAM: CHAR’S COUNTERATTACK, and why Char Aznable’s plan to crash the Axis Zeon meteor into earth is so omnipresent in my thoughts these days.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.