SDFF Review: David Cronenberg's "A Dangerous Method" is disappointingly dull

Film Rating: C–

Your enjoyment of David Cronenberg’s “A Dangerous Method” will hinge entirely on whether or not you are willing to pay to sit through a 94-minute lecture on historical psychology. If you are expecting an effective dramatization of the lives of Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, something resembling an actual film, you will be very disappointed. But if long rambling lectures are your idea of a good time, and you didn’t get enough of them in High School or College, then by all means, see “A Dangerous Method.” Continue reading after the jump...

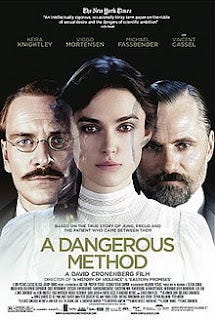

The film begins in 1902, and Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) has just admitted a new patient, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). She suffers from intense hysterics, but rather than use the usual methods of treatment, Jung has decided to test the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen). This prompts Jung to contact Freud for the first time, and the two quickly hit it off as friends while Jung continues to treat Spielrein, herself an aspiring psychiatrist.

That’s the general set-up, anyway. This is not a film greatly concerned with narrative. It instead focuses on long, scholarly discussions of psychology, and given the immense amount of talent involved, the results should be intellectually stimulating. They are not. Christopher Hampton’s screenplay does not attempt to make interesting characters out of Jung, Freud, or Spielrein, but instead uses them as repositories for information I assume Hampton cut and pasted out of textbooks. So rather than have characters actually converse, one person will recite a long passage of psychological theory, then another character will provide a counterpoint taken from a different chapter; many lines in the movie are stripped straight from the writings of Jung and Freud.

The results are oppressively dull. I don’t for a second believe that Freud and Jung talked like this – they were human, like the rest of us, and just because they contributed to all our psychology textbooks doesn’t mean they talked like one – but even had Hampton travelled back in time to confirm the accuracy of his prose, it wouldn’t make for good drama. Drama requires nuance, a level of subtlety that invites the viewer to engage in a back-and-forth conversation with the film. “A Dangerous Method” allows for none of that; it doesn’t ask the audience to analyze what they are watching, to think about the different theories characters present. It is a one-sided experience, where we are made to watch as the characters do all the conversing. There is no room for intellectual audience interpretation. And if we aren’t part of the equation, then what is the point in watching?

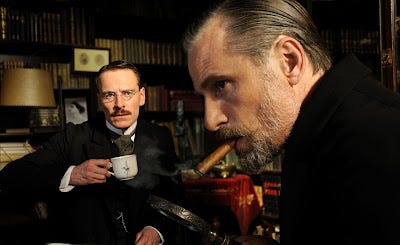

Unsurprisingly, the best part of the film is the only one with nuanced character development: the relationship between Jung and Freud. Their conversations are just as wooden as anything else in the film, but certain scenes display a welcome degree of humanity. As history tells us, Jung and Freud were friends until they had a falling out, and I greatly enjoyed how the film portrayed the inherent frailty of their relationship. Jung is rich and Freud is not; Freud is a little more sensitive and observant, while Jung can be colder and less passionate; intellectually, they disagreed on the role of mysticism in psychology; most importantly, of course, they were from different generations. I wound up sympathizing with Freud; as we know today, many of his ideas were flawed, but he opened a door for other psychologists to walk through. He wanted nothing more than for Jung to walk through that door and continue his work, but in Freud’s lifetime, Jung wound up going in different, possibly destructive directions, and I empathized with Freud’s disappointment.

That probably has more to do with Viggo Mortensen’s performance than any qualities of the script, though. As always, Mortensen is mesmerizing. He’s long since proven he can knock any role out of the park, and his effective, engaging delivery of Hampton’s overwrought dialogue just cements his reputation as one of the greatest actors working today. I felt for Freud because Mortensen brings so much humanity and nuance to the table, and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention how wonderfully Mortensen uses Freud’s trademark cigar as a performance tool.

But Freud is not the focus of the movie; that would be Jung, and though Michael Fassbender really gives as much as he can, the role is just too underwritten to be effective. Though Jung is the film’s central figure, I don’t feel I gained any perspective on him, especially compared to Freud. Hampton can’t decide what aspect of Jung he wants to focus on. His infidelity? His obsession with mysticism? His devotion to curing patients rather than studying them? All would be valid roads to explore, and though the script dabbles in all of them, none are properly developed. Fassbender certainly elevates the part, making Jung a perfectly watchable character, but there’s little he can do with such an underwhelming script. Oh well. Fassbender always has “Jane Eyre,” “X-Men: First Class,” and “Shame” to fall back on come Oscar time, and as such, he walks away perfectly unscathed.

The same can’t be said of Keira Knightley, giving one of the worst performances of her career as Spielrein. She does some effective physical work illustrating the character’s hysteria and how certain impulses are triggered, but she also speaks with an infuriatingly awful Russian accent. Distractingly cartoonish even in its base form, the accent is painfully inconsistent, thick in one moment and almost gone the next. Knightley has no hope of doing good work through this voice, but I wonder how much of that is her fault. Accents in general are incredibly confusing across the board. Jung and Freud speak with a clear, slightly-British inflection, while other German characters actually have an accent. There doesn’t seem to be any logic to which characters are accented and which are not, so I don’t know why Cronenberg found it necessary to saddle Knightley with an unsustainable accent.

In fact, Cronenberg is really off his game throughout the whole movie. It pains me to say that, because he’s a truly great director, but I have to call them like I see them. The cinematography is bland, stagey, and uninteresting, and the editing is often atrocious. Scenes are connected together without any logical flow; one particularly jarring cut sees Freud finishing a speech in one location, then jumping into the middle of another speech somewhere else many hours later. “A Dangerous Method” was originally a stage play, and Cronenberg has done next to nothing to make it look or move like an actual film.

In the end, the film’s only major redeeming aspects are Mortensen and, to a lesser extent, Fassbender. It is completely disengaged from the audience, and gets increasingly tiresome as it moves along. I can’t imagine it appealing to anyone but those who would rather get their psychology lectures in a movie theatre rather than in person, but I doubt that’s a very significant demographic.

“A Dangerous Method” will open in limited release beginning November 23rd.

Though this was the last film I saw at the Starz Denver Film Festival, I have a bit more festival coverage in the coming days! I’ll be posting a round-up of all my festival reviews tomorrow, and on Tuesday, I’m publishing an article full of “awards,” recognizing the best of the festival.