SDFF Review: Michael Fassbender stuns in "Shame," a dark, rewarding portrait of sexual addiction

Film Rating: A

I think I have an addiction.

I can’t control my hyperbole. In September, I vigorously declared Ryan Gosling’s turn in “Drive” as the best performance of the year, forgetting, of course, that we still had many months (and a film festival) to go. Then, in October, I changed my mind, this time calling Michael Shannon’s work in “Take Shelter” the best acting of 2011. Seeing Kirstin Dunst’s mesmerizing performance in “Melancholia” last week reminded me that in both cases, I really should have limited that hyperbole to “male performance” and added a “so far” to all my “best of the year” statements to give room for work like Dunst’s to come along. The night before seeing “Melancholia,” I declared that “Like Crazy” had the best acting of 2011, which was soundly bested 24 hours later. I began to realize my hyperbole problem when I sat down to write my “Melancholia” review, and tried to stop making broad statements about any of element being the best (though I was still content to call it the best film of the year so far). I was taking steps to heal myself.

But today, I’m going to relapse: Michael Fassbender’s crushingly brave performance in Steve McQueen’s “Shame” is the best piece of acting to hit screens in 2011. With all due respect to Gosling, Shannon, Dunst, and all the other tremendous performances to come along this year, I don’t think anything even can come close to topping Fassbender’s work here (and that includes Fassbender’s own fine turns in 2011 movies such as “Jane Eyre” and “X-Men: First Class”). As a sex addict being consumed by his rampant desire, Fassbender bares his heart, soul, and much more for the world to see, but does so with restraint and nuance, making the character feel entirely palpable. Running the gambit from funny to natural to unsettling to frightening, while always remaining, if not likable, sympathetic, Fassbender is simply magnetic, and the film around him is absolutely up to snuff. “Shame” is a flawlessly constructed cinematic treasure that forces viewers to confront some dark, disturbing material; it is as unflinching as it is riveting, and – here I go again – it is one of the absolute best films of 2011. Read more after the jump...

The film deals with an addiction far more serious than my own: Fassbender plays Brandon, a corporate drone in the throws of an intense sexual addiction. Once upon a time Brandon may have used sex for pleasure, but at this point, sex is a distraction, something safe and familiar he retreats to for consistency. He isn’t picky about how he gets his fix, either; he tries seducing women, and is fairly adept at it, but failing that, he hires prostitutes, uses online sex chat rooms, and masturbates compulsively. Sometimes, all he needs is a visual stimulus, as in one scene where he watches porn on the computer as casually as most people would watch YouTube.

Clearly, Brandon has problems, and one of director/co-writer Steve McQueen’s best decisions is to never explicitly explain why Brandon needs sex or what he is running from; Fassbender isn’t given a climactic monologue to lay his psyche bare. Instead, McQueen trusts Fassbender to illustrate all of the character’s intricacies and the viewer to watch closely, to engage with the film and meaningfully dissect the character based on what we are given. I believe all the pieces are there; more than anything else, one must observe how Brandon moves through the world and how he interacts with others. He doesn’t have friends so much as acquaintances, work buddies at best, and one could argue he only hangs out with these men to create a semblance of normality as he tries seducing women. He doesn’t just shy away from meaningful contact, he runs from it, is terrified by it, and he fills these gaping holes in his life the only way he knows how.

The key conflict of “Shame,” then, is the arrival of his sister, Sissy (the wonderful Carey Mulligan), someone he loves but actively ignores precisely because his relationship with her is meaningful. Sissy has plenty of baggage of her own, and in many ways, she’s even more mysterious than Brandon. Mulligan handles the character’s darker side magnificently, suggesting volumes with a single glance, but that’s one her specialties. She’s unrecognizable in the role because, while she tends to play more reserved characters, Sissy is bursting at the seams with playful enthusiasm. She’s impossible not to love, and that’s something Brandon can’t ignore either. Early on, the pair have several casual, friendly scenes together that are as hilarious as they are charming; Fassbender and Mulligan have tremendous chemistry, and it doesn’t take long to establish what these two mean to each other. That’s precisely what scares Brandon so much, and though Mulligan only appears sparingly, Sissy’s impact is felt in every scene.

“Shame” isn’t so much a film about plot as it is about character, giving us a window into the lives of these people at a particularly tumultuous time. It doesn’t have the kind of narrative momentum we are used to, but instead relies on long character-driven scenes that could probably all work out of context as short films. Nevertheless, no moment is anything less than riveting, and I can’t quite put my finger on why. A big part is the acting; Fassbender is piercing and Mulligan is mesmerizing, but James Badge Dale and Nicole Beharie also do some very nice, naturalistic work that keeps us engaged. Each of the scenarios the characters find themselves in are fascinating on one level or another; each explores Brandon’s tormented soul, and since Brandon is such a captivating character, it’s all endlessly intriguing.

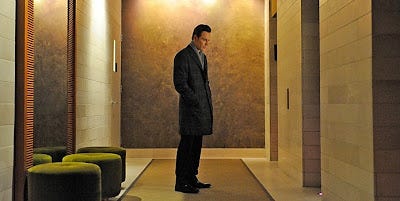

The craftsmanship is a huge contributor to the film’s mesmeric quality. Dramas of this nature don’t often go for the wide, 2.35:1 aspect ratio, and when they do, they tend to waste space: not so here. McQueen uses the large amount of space afforded to say so much about his characters; many lone shots of Brandon place him on one extreme end of the frame or another, expressing the space he inhabits as a loner. He is distanced from the world, and the width of the frame illustrates that remoteness. When he is centered in the frame, he seems uncomfortable, or at least out of his depth. When characters share the screen, they are expertly placed to imply relationships, to say things that are most powerfully expressed visually. There is usually space between Brandon and any other individual, unless that person is Sissy. He is allowed to be close to her; in fact, McQueen practically regards their bond as sacred, so much so that their two key exchanges are framed as close-ups on the back of their heads, giving them a semblance of privacy:

Even more impressive is McQueen’s use of long takes and judicial editing to ensure that the filmmaking never takes us out of the moment. There are some truly incredible extended takes here, including a long tracking shot of Brandon as he jogs through New York; many dialogue scenes contain no cuts, simply framing the actors as they deliver the entire sequence in one go. Even when not using long takes, McQueen cuts infrequently, letting each shot breathe. This isn’t groundbreaking; many older films did the same thing, but one rarely sees such careful, measured editing in modern filmmaking. It’s a real treat, a reminder that more editing doesn’t equate to better editing as so many filmmakers seem to believe these days.

And, of course, McQueen doesn’t flinch from graphic portrays of sex and nudity. “Shame” will be released in the United States with an NC-17 rating; relative to how the MPAA typically treats sexual content, this is sensible. Fassbender’s penis is the star of the opening sequence, Mulligan bares all, and there’s a sex scene near the end so graphic that I have to wonder how they faked it. But “Shame” isn’t pornography, the common connotation of the NC-17 rating. The sex isn’t there to get anyone aroused; it is mechanical, dirty, and more often than not, outright disturbing. It is treated very seriously, and is an integral part of the film’s power. In that sense, “Shame” certainly doesn’t deserve an NC-17 rating. It’s not a film for kids, but for the MPAA to say it’s okay if parents choose to take their little ones to “Saw 14” by rating it R while commercially banning “Shame” with an NC-17 is absolutely outrageous. I hope people see “Shame” for a variety of reasons, but I’d like to imagine it will start a discussion of how we rate films in this country, and why there’s a stigma on allowing filmmakers to deal with adult issues in adult ways.

“Shame” is adult; there’s no mistaking that. But it is also incredibly rewarding, a film where you will take away as much as you are willing to put into it. For some viewers, that will be hard, because “Shame” is not an easy movie to watch or digest; Brandon’s addiction holds a mirror to our own lives, to the destructive drives we all have to get ourselves through the day. It’s a challenging movie, but I was captivated from the very beginning and only grew increasingly engaged as the film spirals towards its impactful conclusion. For the sake of spoilers, I have many, many thoughts on the film I haven’t shared here; I hope readers will check out the film when and if it comes to a nearby theatre, and once a few months have passed, I’m definitely going to revisit this one, just as I have done with “Drive” and “The Tree of Life.” There’s a lot to discuss, and “Shame” isn’t the kind of movie that fades once the lights go up.

2011 hasn’t been a great, or even particularly good year for movies. But we’ve already had a handful of vast, rich experiences, and “Shame” is one of the most expansive. I’d rather take a few masterpieces like this over a whole year of good, solid films any day. I hope “Shame” reaches audiences everywhere, and I strongly urge viewers to check it out if it does.

“Shame” will go into limited release, starting with New York and Los Angeles, on December 2nd.