Springsteen Sundays: Book Review - David Burke's "Heart of Darkness" is a fantastic analysis of Bruce's bleak masterpiece, "Nebraska"

In case you missed last week’s debut column, here’s the short explanation of my new Sunday feature: readers really liked my Wrecking Ball coverage (and drove site traffic through the roof), I’m a Bruce Springsteen maniac, and I’ve therefore created a new weekly column wherein I explore whatever Boss-related thoughts are on my mind. It’s called Springsteen Sundays.

This week, I’m sharing a paper I wrote for my “Intro to Journalism” college class. We had to read a book involving journalism and write a review, and I somehow convinced my recitation advisor to let me write about the new book I’d just bought, Heart of Darkness: Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, by author David Burke. It’s a pretty great read for Springsteen fans, and I definitely wanted to shed some light on it in this column.

Read the review after the jump…

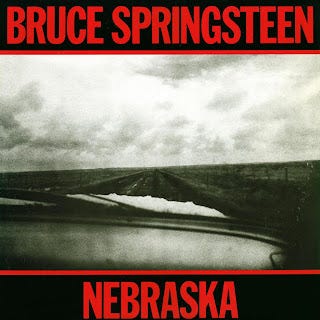

The original LP cover for "Nebraska"

In Heart of Darkness: Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, author David Burke outlines the history of Bruce Springsteen’s career and work in relation to his 1982 studio album, “Nebraska.” He argues – as many have over the last thirty years – that “Nebraska” isn’t just Springsteen’s greatest creative accomplishment, but also one of the most significant artistic works of the twentieth century, with literary merits rivaling John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and widespread musical influence lasting to this very day. Using newly conducted and archival interviews with musicians, historians, and writers, he explains the fascinating history of the album’s writing and recording, places it in the context of Bruce’s entire forty-year recording history, and explores the history of American folk music and accompanying social trends that led to “Nebraska.”

It is a captivating, revelatory read for Springsteen fans, even those who, like me, foolishly thought they’d gleaned all there was to know from the Boss’s body of work. Burke’s central, unstated thesis is that Bruce’s entire life and career, all his experiences, mistakes, and triumphs, ultimately revolve around “Nebraska;” every song he wrote before was merely building to this extraordinary moment in musical history, and every album afterwards can be traced back to it. Burke’s argument is a bold one, at least for the hardcore aficionados who have their own opinions on every inch of Bruce’s career. Of course, these same people (including yours truly) require little convincing of Burke’s second core thesis: that “Nebraska’s” stark, uncompromising view of our nation’s dark side makes it one of the most significant poetic works in American history. Still, it’s nice to see the album’s importance explained in such thoughtful, clear, and powerful ways.

The inner-sleeve of the "Nebraska" LP, using one of

David Michael Kennedy's fantastic Bruce portraits

I believe Burke succeeds in convincing the reader of both of his core cases, chiefly because of the journalistic maturity he brings to his writing. It’s not an ‘objective’ look at Springsteen and “Nebraska,” as Burke has clear opinions on all of Bruce’s work and American politics, but he also doesn’t ask that we take his opinion as gospel. Burke has interviewed a large swath of musicians and cultural historians, including some close to Bruce, and gives over long stretches of the text to their thoughts. These passages are fascinating; Judy Collins’ lengthily exploration of folk music is enthralling, audio engineer Toby Scott’s anecdotes about the album’s unusual recording process are equal-parts hilarious and informative, and “Nebraska” photographer David Michael Kennedy’s recollections of working with Bruce are absorbingly intimate. Those are only a few of the voices Burke has collected to help tell the story of “Nebraska” and, by extension, America itself. In addition to his own interviews, he’s dug up wonderful contemporary quotes from articles, reviews, biographies, and of course, Springsteen himself. Burke even devotes the last thirty pages to testimonies from artists and critics who have been influenced or moved by “Nebraska,” taking himself out of the equation to let others illustrate the album’s social significance.

In this way, Burke hasn’t merely written a history, but assembled a tapestry of voices, viewpoints, and visions that say more about Springsteen, our nation, and its people than one writer ever could. To my mind, that’s the goal of good journalism: to tell a story bigger than oneself by convincingly placing one’s subject in a broad social context. Burke even recounts an interesting behind-the-scenes tale that illustrates an ethical quandary: when he tries reaching out to Springsteen’s management for an interview, he is continually, silently rejected, leading him to question how Bruce and his image are managed. It’s something Burke could easily have left out of this narrative, but since the anecdote presents noteworthy queries about his subject, it adds greater journalistic weight to the proceedings.

Burke’s prose is sparse, direct, and engaging, economically packing lots of information into each of his relatively simple sentences and paragraphs. This makes Heart of Darkness a fast read, as Burke grips you early on and moves with a brisk, uninterrupted flow that makes the book at times impossible to put down. His own critical assessments of Springsteen’s work are consistently insightful; even if I don’t always agree with his opinions, Burke’s assertions are all rooted in the lyrics – he only occasionally reads into the songs, and calls himself on it when he does so – and recordings. There are a few instances when he states an opinion without properly elaborating – such as his underdeveloped disdain for the song “The Hitter” – but these moments are few and far between. He has a strongly liberal political stance, but again, this is rarely obtrusive, and appropriate given Springsteen’s own leanings; for the most part, he backs up his political statements with facts and sources, save for a rather extreme assessment of George W. Bush's presidency and the 9/11 attacks that would ideally take some more explaining.

Another Kennedy photo, used in promotional

material for "Nebraska"

Burke also knows his audience; it’s unlikely that most readers will purchase a book focusing on a particular artist and album, so Burke forgoes catering to the casual fan. He expects you are a hardcore Springsteen aficionado familiar with all of Bruce’s albums and songs; even for the most obscure tracks, Burke doesn’t summarize the lyrics, because if you’ve paid $20 to read a 200-page book about a specific studio album, chances are you know them all by heart. Indeed, I personally don’t need any handholding when it comes to Bruce, so I greatly appreciate this direct, scholarly approach. In a perfect world, this book would educate the uninitiated to the album’s cultural significance as well, but it’s just not a subject a wide audience is likely to gravitate towards, so I’m very glad Burke didn’t try having it both ways.

In any case, Heart of Darkness is a terrific examination of how art and society intersect. If Burke definitively proves one point over the course of the book, it’s that “Nebraska,” like the works of John Steinbeck, Flannery O’Connor, Martin Scorsese, Woody Guthrie, etc., captures the dark essence of the American dream, shedding light on a hidden world we’d rather not face but live in all the same, and does so in a way that will forever stand the test of time. “Nebraska” is an aesthetically and thematically significant classic that deserves to be uttered in the same breath as the great American novels, poems, and films, and Burke has used a journalistic approach to make this abundantly clear. I loved “Nebraska” to death going into this book, but I walked away with a substantially higher estimation of it. I still don’t know if I’d call it my favorite Springsteen record – you know, the one I’m tempted to put on each time I hop in the car – but I am now perfectly willing to acknowledge it as his greatest artistic accomplishment. Swaying a die-hard Bruce fan like that is a feat few writers could pull off.

The landscape portrait used for the cover of "Nebraska."

David Michael Kennedy took it years before it was used.

If you enjoy "Springsteen Sundays," please consider donating to

"Jonathan Lack at the Movies" to support future columns: