Star Trek Sundays: "The Motion Picture" is an unsung masterpiece

Especially in its 2022 4K Director's Edition

It’s Sunday, and we’re beginning a new project of going through all 13 theatrical STAR TREK films, a series that will include a number of pieces that have never appeared online before taken from my book 200 Reviews, available now in Paperback or on Kindle (which you should really consider buying, because it’s an awesome collection!). We begin today with a movie near and dear to my heart, STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE. Enjoy…

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (& Director’s Edition)

1979 / 2001 / 2022, Dir. Robert Wise

Originally published in 200 Reviews, based on an excerpt of a previously unpublished project written in 2013, and notes from 2022

With a legendarily difficult development and production, and a generally tepid response among fans and audiences since its release, Star Trek: The Motion Picture it is typically looked upon as an outright failure at worst, and a creative disappointment at best. The film may have brought Star Trek back into existence – it was an enormous hit at the box office – but from the moment it was released, The Motion Picture has had, to put it kindly, a tepid reputation.

Not for me, though. When I look at The Motion Picture today, putting the storied history and popular response to the film out of my mind as best I can, I see a remarkable accomplishment that transcends the time and conditions it was made in to encroach on ‘masterpiece’ territory. I thought the same thing when I saw the film for the first time, many years ago now on DVD, when I was just a kid, and mostly incognizant of the film’s history and reputation. The experience absolutely blew me away. I had been steadily watching The Original Series on DVD, after working through all of The Next Generation with my father, but this was different. Watching The Motion Picture, I felt challenged, provoked, and ultimately uplifted, falling head over heels in love with the film. I was convinced it was the most powerful piece of Star Trek fiction I had yet encountered.

But in the following days and weeks, I learned much more about the film’s reputation, all of which was deeply cynical and in no way reflective of the movie I had seen and loved. I could find no one else who agreed with me, not even my own father, who had himself disliked the film when he saw it during its theatrical debut. The cynicism surrounding The Motion Picture was so clearly omnipresent that I foolishly chose not to return to the film for a long time. I wanted to maintain my positive memories, worried that whenever I returned to The Motion Picture, I would be tainted by the surrounding cynicism, and unable to ever enjoy it again.

That is not what happened, however. Returning to the film upon its 2009 Blu-ray release of the original theatrical cut, I found my doubt washing away immediately, replaced with passion and inspiration even more powerful than the love I had felt the first time around. I am convinced that The Motion Picture is a near-masterpiece, and I think I can finally articulate my feelings, and perhaps, in the process, explain why the film has the capacity to baffle and frustrate some audiences while it uplifts and amazes viewers like me.

This is the nature of many great works of art, after all, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a true work of art, make no mistake about that. Even those who do not like the film can hopefully agree on this point. It is a wildly, impossible ambitious work, one that is keenly in tune with the franchise’s intellectual roots. Gene Roddenberry never meant for Star Trek to be the action epic it is so often presented as, but set out to make a work of pure science fiction, a series that would look to the future to examine issues of the present, presenting a vision of humanity as it could be to discuss the human condition as we currently understood it.

The Motion Picture, like it or not, is the closest any Star Trek film would ever come to representing Roddenberry’s vision. It is, arguably, the purest presentation of Roddenberry’s core ideals that exists in the entire franchise. Speaking from personal experience, I have seen many dismiss the film for this very reason, referring to it as an overlong extension of the television series. This is not a completely unfair assessment, but it is an incomplete one. The Motion Picture is rooted in the core intellectual concepts of the television series, but it differentiates itself by being an almost entirely experiential creation, something only film, among all visual art forms, is best equipped to deliver.

What do I mean by experiential? I am referring to The Motion Picture’s focus on aesthetics, constantly prioritized over narrative and, in a certain sense, character elements. To tell the story of the Enterprise’s encounter with the V’Ger cloud, a massive, dangerous, inscrutable force heading for Earth, the film’s visuals, stunning and rapturous, work in total harmony with Jerry Goldsmith’s remarkable musical score to create a sense of ‘experience,’ something total, enveloping, and immersive. The film presents us with a seemingly endless series of dense, detailed, imaginative images, coupled with music that underlines the grandeur of such imagery, and the key to interpreting and developing a personal understanding of the movie is rooted in the emotions one feels while watching such aesthetic force unfold.

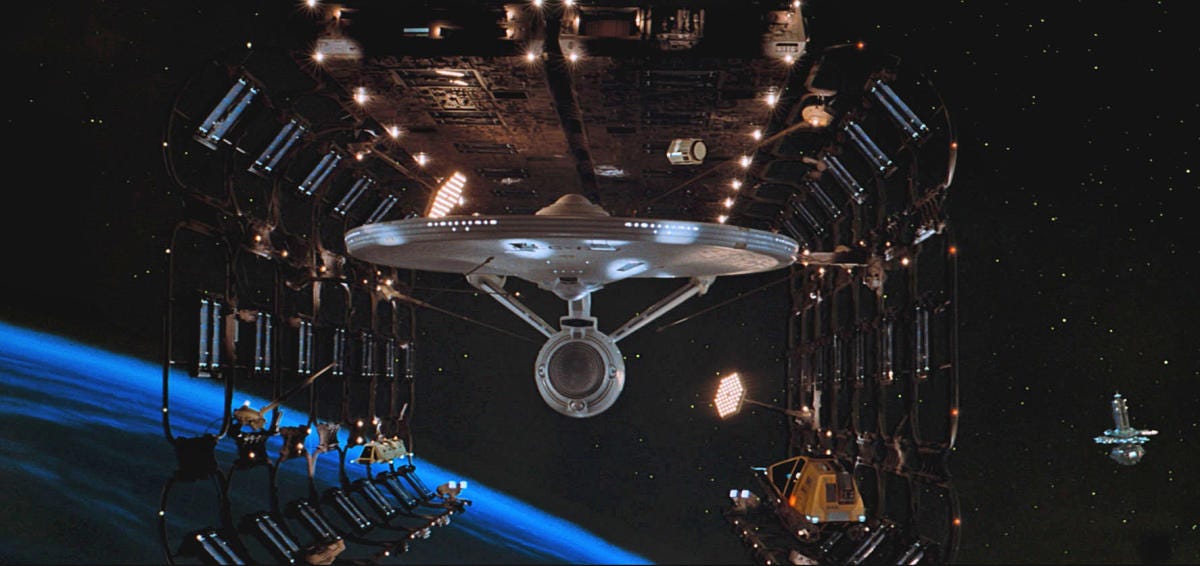

The Motion Picture is often remembered for the many long ‘observational’ sequences it contains, such as a scene early on where Kirk and Scotty shuttle to the Enterprise – and, in the theatrical cut, take six minutes to do so. Later, inside the V’Ger cloud, a good ten minutes or more are devoted to taking in all the haunting, fantastical sights the cloud contains, cutting back continually to the crew’s reaction shots. These sequences are legendary not only for their length, but for the lack of narrative momentum. Nothing technically ‘happens’ during these stretches, and yet such scenes make up a large chunk of the film’s run time. How one reacts to these observational sections likely summarizes one’s overall opinion of the movie. Many find them boring. I, personally, find them exhilarating.

Either way, these stretches are not ‘bad’ or ‘lazy’ filmmaking, but a very intentional, extremely significant part of the film’s basic language. Nothing ‘happens’ when we observe the cosmos in The Motion Picture, because the observation itself is the given purpose. Spending such long amounts of time in the eyes of the characters – the recurring reaction shots suggest we are witnessing their points of view – connects us with them, an essential bond that will lend us empathy throughout. More importantly, the film attempts, through its imagery, to instill a sense of ‘totality’ upon the viewer: The totality of space, of existence, and of human understanding. It is not necessarily aiming to ‘entertain,’ but to enlighten by presenting a vision of something greater than ourselves.

Is this not the essence of space travel? The core reason why we, as humans, are so fascinated by space and the great beyond? The cosmos is not just bigger than us, but bigger than all things. It is inherently unknowable, because our minds cannot comprehend its vastness, or the wonders it may behold. We are fascinated by the things we cannot understand, and in encountering V’Ger, the crew of the USS Enterprise is confronted with something more fantastic and inexplicable – and, therefore, mesmerizing – than ever before.

This simple yet profound feeling is core to Roddenberry’s larger intellectual and thematic concepts, and it is a testament to Robert Wise’s skills that such a feeling can be instilled in the audience. No matter one’s opinion of the film as a whole, I believe it is objectively obvious that Wise’s direction is superb, for the imagery he crafts is glorious, intoxicating, and unbelievable, even by today’s standards. The Motion Picture was an immensely expensive production, and one of the most effects-heavy films of the period. Even with films like Star Wars and Superman in existence, the ambition of The Motion Picture charted an entirely new frontier for visual and special effects, and while the finished product is hardly perfect – countless visual anomalies present themselves throughout the theatrical cut – it is remarkable that Wise was able to go as far as he did.

The starship models are as detailed, thoughtful, and awe-inspiring as those in Star Wars, a major step up from the simplistic creations of the Star Trek television series, while the surreal, unpredictable landscapes of the V’Ger cloud rivals any modern CGI in terms of pure imagination and effectiveness. The cinematography, by veteran photographer Richard H. Kline, creates a wonderful expansiveness of its own, and is the most technically adept and compositionally superb of the entire film series.

These elements, and many more, are essential in making The Motion Picture function as intended. Jerry Goldsmith’s score – the best of his legendary career, and one of the greatest ever composed for film – is equally crucial. Music is the manifestation of ‘pure emotion’ in the film, and as ‘emotion’ is equated with ‘humanity’ throughout the story, it is the music that manages to forge a strong, immediate bond between the vastness of the visuals of the comprehension of the viewer. By watching, and listening, we become in touch with the film’s approximation of eternity, and with all the possibilities it holds.

This alone would be enough to impress, for it is a staggeringly ambitious feat to attempt. Yet where I believe The Motion Picture exceeds ‘impressive’ to near the territory of ‘masterpiece’ is in its ability to tie its cosmic, experiential journey to something intensely human and profoundly meaningful: A meditation on who we are and where we belong in the Universe.

In confronting the V’Ger cloud, the Enterprise contacts a being that has seen and documented the vastness of the universe. It has collected, felt, and experienced a great deal of the cosmos, and appears, because of this, to be just as unknowable and untouchable as the universe itself. A sense of being ‘dwarfed’ therefore pervades the film. The Enterprise and its inhabitants are not just dwarfed by the wonders of space, but by the possibilities V’Ger shows, possibilities we, as seemingly insignificant humans, cannot possibly grasp.

But as the film goes along, this reading is shaken. First, Spock discovers that there are other ‘universes,’ existing outside the literal, that V’Ger, as a being of technology, cannot grasp. V’Ger cannot feel emotion. It is cold. Distant. It will never know love, or friendship, and while it can collect data on all of time and space, it can never ‘transcend,’ because it cannot understand what exists beyond the clearly perceivable ‘reality.’ Thus, Spock – and, by extension, the viewer, who is always made to experience these events and revelations empathetically – learns that though we cannot tap into the literal vastness V’Ger has seen, we are, as creatures of emotion, already in touch with something greater, and more inexplicable, and in many ways, more amazing. The wonders that The Motion Picture shows us – countless miraculous cosmic vistas, and remarkable technological landscapes, and never-ending images of space at its most beautiful and foreboding – are contained within us, for in our ability to feel, we are inherently in touch with the Universe. We are creatures of transcendence. The Motion Picture, in this way, reveals something at the core of humanity; it makes the dense fathoms of the human soul literal by personifying them in the vastness of space.

The film then goes one step further. At the climax, Kirk and company learn that V’Ger is actually the Voyager space probe, and therefore comes from us. It is a personification of our need to explore, to discover – our curiosity made manifest, and taken to its logical conclusion. 300 years after it is launched, this monument to humanity’s thirst for knowledge returns having experienced more than we could ever imagine, and all of a sudden, what the Enterprise crew (and the viewer) felt was inexplicable and unknowable is revealed to be an extension of ourselves. An extension that must return to us, centuries later, because it shall always be incomplete. No matter how much it has gathered – the Universe itself, as McCoy puts it – it cannot progress further, cannot transcend, unless the human element is assimilated.

Is that not a beautiful, inspiring notion to consider? That in the end, what we create must come back to us, because while space and the universe and all the things we do not know are impossible to grasp within a lifetime, the tools needed to ultimately do so exist, complete and bursting with potential, within the human spirit. We are children of this universe, and because we come from it, and shall eventually return to it, we are, inherently, in touch with it. Realizing this, and coming to terms with it, is a form of transcendence in and of itself, a heightening of consciousness that is real and beautiful and absolutely meaningful – and I believe Star Trek: The Motion Picture is not merely suggesting such major, transcendental ideas, but is capable of creating such an experience through its very presentation.

All of this is there in the original theatrical cut of the film, which was created under such tight deadlines and with such ambitious effects work that Robert Wise considered it unfished; he wrote that “we had [to remove] several key dialogue scenes in order to accommodate the incoming effects work, but no time remained to work properly on balancing these two components.” No test screenings were held, and work continued so late that Wise personally delivered the just-completed print to the film’s world premiere. When the Star Trek films were released on DVD, Wise was given the opportunity to, in his words, “complete the film,” creating a “Director’s Edition” for DVD that found what he felt was a “proper editorial balance for the film,” while also completing “those effects shots and scenes which we had to abort in 1979,” and give the film “a proper final sound mix.” This version was released to DVD in 2001, and definitely prompted a minor critical reevaluation, but it was always held back by the technology of the day. The edit was created, and the new effects produced, for standard definition DVD as a digital master, meaning it couldn’t just be re-scanned in 2K or 4K for subsequent Blu-ray and Ultra HD releases. As a result, when the Blu-rays were released in 2009, the film reverted to its original theatrical cut, which was again re-issued when the films were released on 4K in 2021; all the while, the Director’s Edition remained stuck on a very old, not-particularly-great-looking DVD for many years.

This strange détente finally ended in 2022, when Paramount greenlit the creation of a full 4K recreation of the Director’s Edition, first for release on their streaming service Paramount+, and then on 4K Blu-ray later that year. It is, I believe, one of the all-time great feats of film restoration and reconstruction, a monumental accomplishment that reveals how fully unfinished the film was in 1979 – and how, now completed, it finally stands tall as a masterpiece, no qualifiers needed.

Robert Wise passed away in 2005, but a team of talented industry veterans, including those who had helped him assemble the original Director’s Edition in 2001, handled the work here, and with a much larger budget and many more resources than they had twenty years ago. The result is so much more than the same 4K scan of the theatrical cut from 2021 with a few nips and tucks. The team completely rebuilt the film from its original elements, in both video and audio, in line with Wise’s editorial choices from 2001, and when I say ‘completely rebuilt’, I mean it. The team not only went back to the original negative, doing much needed clean-up and color correction and making countless small fixes, but they even returned to the original VFX elements, the separate pieces of filmed material that were composited together to create the final images in 1979, and re-scanned and re-composited everything with modern technology. I am unaware of any other cases where this has even been attempted; the result is that, and I say this without hyperbole or exaggeration, you have never seen practical effects look this clear in a motion picture. All of the astounding effects shots created by the great Douglas Trumbull and his team, freed from the generational loss of detail that resulted from old optical printing techniques, now appear to be unfolding before our very eyes. All of the wonder I described earlier, in those long sequence of the crew observing the marvels of space unfolding before them, are magnified tenfold in this version.

The sound mix is just as crucial, and just as impressive a restoration effort; the team discovered all the original ADR takes by the cast, many of which had been thought even by Wise himself lost to time, and used the director’s preferred takes, some of which we have never heard before, along with additional sound effects, background dialogue, and previously unused musical cues. It is all combined in a new object-based Dolby Atmos mix that is quite possibly the greatest sound mix I have ever heard for a single film, particularly for its employment of the legendary Jerry Goldsmith score, which is so full bodied, clear, and rousing that it sounds as though it is being performed in the room alongside the viewer.

The actual changes to the film’s edit are largely pretty subtle, but then, editing is a subtle art – small changes can have major ripple effects, and that is most certainly the case here. Wise’s Director’s Edition both adds to and removes material from the theatrical cut, and it all adds up to a more focused and fully-realized experience, with all these quietly, intricately criss-crossing character arcs building on one another against the backdrop of the encroaching V’Ger. Perhaps the single most important moment of the movie, the one that truly ties everything together, is only found in the Director’s Edition; a scene where Spock, on the bridge, begins weeping for V’Ger, realizing that it has become what he himself was trying to achieve through Kolinahr – the purging of all emotions – and, having rejected that empty way of life, coming to empathize with its pain.

The 2022 Director’s Edition is, in short, a finished film, one that illustrates just how much the theatrical cut was, essentially, a workprint, a peek through the keyhole at a truly towering work. The soul of this movie shines so brightly now; it is smart and beautiful and deeply felt, one of the most ambitious Hollywood blockbusters ever, a movie of profound wonder and emotion. This edition, this glorious cinematic rescue mission, elevates the film to the upper echelons of cinematic sci-fi and spectacle.

I love this film, and in its finished version, I may love it more than any other Star Trek movie, because the film is so precisely crafted, carefully paced, and meticulously detailed, featuring a minimalism of plot to maximize the experiential qualities necessary to find the vision of transcendence Roddenberry and Wise mean us to see. Star Trek, in its original inception, is intellectual, and its intellect is aimed at exploring the biggest of big ideas. The Motion Picture is, as its title suggests, is a much larger version of this. It is in many ways the ‘ultimate’ Star Trek production, for it asks bigger questions, takes us to places more alien and unknowable, and ultimately connects back with the basic human experience – the basis of all good Star Trek fiction – more powerfully than any other Trek production. It is, perhaps, Star Trek at its purest, and for that, I find the film not just remarkable, but valuable, an essential piece of the Star Trek tapestry.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.