Jonathan Lack's Top 10 Films of 2017

No matter where you looked for cinema, 2017 was a great, rich, and varied year for the art of film.

It was most assuredly not a great year for the business or culture of film, and this must be addressed before we get back to the art, for any assessment of 2017 would be grossly incomplete without that consideration. A growing revolution in American culture had a major part of its epicenter in the film industry, as the abuses of a seemingly endless parade of awful, powerful men were revealed, exposing an insidious and systemic rot that has hurt more people and robbed the world of more great careers than we may ever truly understand. Multiple online film coverage outlets and the gatekeepers controlling them were similarly outed, while a major theatre chain whose arms extend into film festivals, distribution, and much of modern film culture was revealed to have a CEO who actively covered up and enabled a serial sexual harasser. No American industry, no segment of American life, has been or will be immune from the #MeToo wave, nor should they be, for this is a systemic cultural cancer that we are all of us, men especially, responsible for recognizing and taking active steps to improving. But the entertainment industry was a major and critical part of this revolution, and will continue to be going forward, and as long as we enjoy and discuss and write about film or television, we must also be vigilant in supporting the voices of those who have been hurt and working, in whatever small or large ways we can, to change and improve our culture going forward.

But as small as it all can seem in the face of such widespread abuse and suffering, let us return to the art. I find it remarkable not only how many truly great films were released in 2017, but in how many places they could be found. From the smallest arthouse to the biggest multiplex, 2017 offered a steady stream of smart and soulful artistic accomplishments. Hollywood’s tentpoles were far better than average, with the creatively resurgent superhero genre having its best year to date – Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman and James Mangold’s Logan both rank among the genre’s greatest entries – while some of our most interesting commercial filmmakers delivered great new experiences, from Matt Reeves’ biblically scaled War for the Planet of the Apes to Steven Soderbergh’s effortlessly charming Logan Lucky. The festival circuit was particularly rich, and I found most of the glut of year-end ‘awards’ films unusually compelling, from Guillermo del Toro’s impossibly sweet The Shape of Water, to Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris’ insightfully mounted Battle of the Sexes, to Scott Cooper’s thoughtful revisionist Western Hostiles, to Steven Spielberg’s wildly timely and wonderfully performed The Post. Streaming once again gave home to some real gems, like Dee Rees’ piercing period drama Mudbound, and the entire year was peppered with under-the-radar gems like Matt Spicer’s social-media-stalking comedy Ingrid Goes West or the documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, which is one of the great films ever made about the artistic process. And I don’t even know what category it fits in at this point, but John Wick: Chapter 2 kicked an unholy amount of ass.

None of these films are on my Top 10 list.

I found 2017 a particularly competitive year, for all the reasons outlined above. My Top 5 came together pretty quickly, and it then took a lot of watching and rewatching and hand-wringing to whittle down the next 5. But the final list feels like a very good summation of my personal journey through film this year, and it was extremely rewarding to write about each of them for this piece. I have structured this year’s list a little differently than the past, leaning in to my own allergy to brevity and writing a miniature 3-paragaph essay for each movie, with a longer piece for my #1 film. I wanted to lend a little more substance to the list this year, both because I didn’t have the chance to write full reviews of most of these films, and because writing at a more ‘academic’ length simply comes more naturally to me. The result is one of my favorite Top 10 lists I’ve ever had the pleasure to write, and I hope it is one you enjoy.

So without further ado, continue reading after the jump for my Top 10 Films of 2017…

10. Star Wars: The Last Jedi

Directed by Rian Johnson

The latest in what seems increasingly likely to be a never-ending parade of Star Wars movies begins with two scenes that make it abundantly clear that, for this film at least, we are in the very best of hands. In the first, Rian Johnson delivers the greatest cinematic space battle in the franchise’s 40-year history, a symphony of aerial action so fluidly composed and expertly character-centric – even though the emotional lynchpin is a woman we’ve never met – that it works practically as its own short film. In the second, we resume from the cliffhanger of 2015’s The Force Awakens, where Daisy Ridley’s Rey offers Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker his lightsaber, only for Luke to take it, chuck it nonchalantly over his shoulder, and walk away annoyed. And in these two scenes, The Last Jedi establishes everything that makes it wonderful: First, that it will be a Star Wars movie made with a unique amount of skill and visual invention, and second, that it does not give a toss about holding on to the past or stoking fan theories. It is here to tell its own darn story, and it’s going to tell it with style.

And tell it the film does. The Last Jedi is the most liberated, engaged, and exhilarating film the franchise has produced since 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back, critically interrogating the series’ past, challenging our preconceived notions, and providing organic, well-earned surprises at nearly every turn. Imperfect in large part due to the sheer scope of the film’s ambition, The Last Jedi is narratively and thematically cleaner than it may appear at first – the entire narrative spine is based around a tactical retreat, and the thematic core is about learning from failure and living to hope another day – and although it grows a bit too diffuse in the middle, it is consistently driven by an overwhelming sense of passion, exquisite character writing, and the best ensemble – of actors and of characters – the series has ever had. And it all comes together for a beautifully interwoven character-driven finale that provides the most aesthetically awe-inspiring material in franchise history, a culmination as bold and harrowing, in its own way, as the finale of Empire.

Two years ago, I declared my love for The Force Awakens loudly and proudly, and while I don’t regret that – the film came at a time in my life when I very much needed it, its warm and comforting presence helping remind me why I fell in love with movies in the first place – The Last Jedi is a clear step up, a film that proclaims and proves that Star Wars can have a bright cinematic future beyond remixing past successes. In that way, it is one of the year’s most fascinating and invigorating experiences, a big slice of pop culture mythmaking at its absolute finest.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi is now playing in theatres everywhere.

9. The Florida Project

Directed by Sean Baker

The Florida Project is a brilliant, beautiful, utterly original miracle of a movie, and it feels so brutally, painfully real that I’m not sure I will ever have the stomach to sit through it again.

While I haven’t heard anybody claim the film is an unabashed bundle of fun, many critics have reported feeling a palpable joy mixed in with the film’s sadness, and I understand where that comes from. The performances director Sean Baker gets from these kids, the sheer authentically playful naturalism with which young star Brooklynn Prince in particular performs, are a wonder to behold, and their surroundings are, from start to finish, impossibly colorful, a world of starburst pastel paints and tangerine orange suns dotted with an endless array of greens. But none of this made me, personally, feel ‘joy.’ Moonee feels so much like a real, living child, as if Baker simply found her down in Florida and fired up a camera without giving direction, that it only breaks my heart all the more given how clearly the film depicts a world that has already and irrevocably failed her. Those pastels and sunsets consistently took my breath away – the film’s exquisite cinematography, by Alexis Zabe, looks like the kind of movie Wes Anderson would make if his life and interests went in a very different direction – but all I could think about was how all that apparent eye candy was surrounding and, in many ways, pasting over the broken world of Florida’s detritus, a world of people barely managing to survive in the swamps left behind by the magnetic forces of tourism and commerce. So while I understand the impulse to feel some of that joy – through Moonee’s eyes, after all, the world is a truly wondrous thing – it is more accurate to say The Florida Project instilled in me a powerful sense of anxiety and sadness.

To be clear, I say none of this as a criticism, and only as an explanation for the powerful way the film worked on me. I think Baker’s film is almost singularly brilliant in how it builds and portrays this world – the role of Disney World, almost never seen but its mesmeric allure constantly felt, is one of the film’s smartest and most damning ongoing threads – and I would put this on the shelf with films like Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (Brazil, 1980) or Luis Buñuel’s Los Olvidados (Mexico, 1950) as one of the great and impactful films about children in poverty and peril. That Baker can paint such a portrait here at home in America, with a world whose aesthetics are in a constant push-and-pull with the underlying themes, and where the children do not have to be caught up in crime or overt violence for it to feel like a tragedy, only makes The Florida Project seem all the more impressive by comparison. This is the film on the list I saw most recently, and one I am still actively digesting, but I have no doubt that it is one of the year’s most intelligent, passionate, and accomplished films, one that is never easy to sit through or absorb but endlessly rewarding to experience.

The Florida Project is now playing in theatres in limited release.

8. Dunkirk

Directed by Christopher Nolan

In many ways, Dunkirk is one of the more ‘imperfect’ films on this list. It has a few narrative digressions and dead-ends that are too predicated on characters making baffling decisions, the time-dilated triptych structure, while largely effective, is occasionally too complicated for its own good, and the script falters whenever characters have to open their mouths and speak (which is, to be fair, infrequent). And then there is the issue of the film sidelining soldiers of color and women from its narrative, an omission for which there is no good excuse.

But art is not a checklist of ‘good’ qualities versus ‘bad’ ones, and where Dunkirk excels, which it does in spades, there is simply nothing else like it. Few cinematic experiences are as wholly immersive or visually and sonically engaging as Dunkirk, a film that places the viewer right inside the heart of the action, minimizing individual characters to make the harrowing scenario itself the focus of our attention and empathy. It is all done with such immense skill, at all levels of production, that it can feel like an out-of-body experience at times, particularly whenever Hoyte van Hoytema’s incredible cinematography takes to the skies for the best and most awe-inspiring aerial photography I have ever seen on film. Shot almost entirely on IMAX film stock, with portions on standard 65mm, Dunkirk is one of the decade’s richest visual experiences, no matter how one views it, consistently summoning a dark, sublime beauty that remains astonishing no matter how many times I see the film. And it is all done in service of a story that, individual quibbles aside, smartly and movingly depicts the value in surviving to fight another day.

I have seen Dunkirk three times now, and liked it more with each viewing. Its faults are clear, but few directors swing as aggressively for the fences as Christopher Nolan, and few bring more skill to bear when they do. As an act of pure, experiential filmmaking, Dunkirk is unlike anything released in the commercial space in years; rarely does a filmmaker get to experiment this boldly at this high a budget. This is one of the great War movies, a significant innovation in the genre and, indeed, one of the year’s best films.

Dunkirk is now available on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download.

7. Get Out

Directed by Jordan Peele

Perhaps the most iconic and inescapable film of 2017, my instinct is to say there’s not much to write about Get Out that hasn’t already been written. But then, I think, that is a foolish thought, for Get Out is one of those films we will be watching, studying, evaluating, and re-evaluating for many years to come. With a film this smart and this rich, there will always be more to say, and I suspect there’s a whole generation of writers and scholars who will do great work saying it.

Get Out is going to be one of the great ‘film school’ standbys going forward, and for all the right reasons: Because it is skillfully crafted, wickedly intelligent, rich in symbolism and powerful visual storytelling, deeply knowledgeable and pointedly subversive in the pieces of film and cultural history it uses as building blocks, and which blends all its pieces to create something bold, original, and utterly of the moment, taking and reconstructing fragments from our past and present and building on top of them to say something no one has ever quite said on film, certainly not in this particular way. Jordan Peele, in one of the year’s great directorial debuts, has a unique and penetrating eye upon the world, and he deploys it here for a film that feel revelatory and essential.

Get Out is also, it should be said, a wildly entertaining and endlessly engaging film, a quality that should not be lost in the critical mix, lest one make the movie sound like homework. The film is littered with great acting – Daniel Kaluuya gives a tremendous breakthrough performance, while known quantities like Catherine Keener, Bradley Whitford, and Allison Williams all do amazing work subverting their own on-screen personas – is frequently visually arresting, has laughs in spades, and works magnificently in horror and thriller veins when it needs to. There is bountiful good reason why Get Out is one of the most universally acclaimed, enjoyed, and discussed films to come along in years; this is a film that has earned every inch of its reputation.

Get Out is now available on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download.

6. Blade Runner 2049

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

If you told me several years ago that the project that would eventually become Blade Runner 2049 would be one of the greatest and most artistically accomplished film sequels ever made, I would have found the idea ludicrous. First, because sequels to 30-year-old films are a pretty creatively bankrupt subgenre, and second, because while the original Blade Runner is one of my very favorite films, it is such a strange blend of happy accidents, warring interpretations, and, yes, artistic inspiration that the mere idea of doing another one, of any kind, seemed impossible.

The key to Blade Runner 2049, then, is that it’s not a simple or direct sequel. Other than Harrison Ford and co-writer Hampton Fancher, it has a completely different cast and creative team, moves the action 30 years in the future to craft its own spin on Ridley Scott’s world, and has a style, voice, and narrative structure that, while clearly influenced by the first film, is largely its own. It exists in both thematic and metatextual conversation with the original, taking the core idea of interrogating humanity in a world increasingly devoid of it and viewing it through the opposing lens of a Replicant’s eyes and, more importantly, heart. As K, Ryan Gosling does the best work of his career, beautifully tracing the complicated internal arc of a man trained to believe he is an object, coming to chase a glimmer of hope that he might be real underneath it all. Where that arc goes, both narratively and thematically, is consistently challenging, surprising, and thought-provoking, and it makes for a film that is at once both sadder and more subtly hopeful than the original.

Gosling is surrounded by an excellent cast – Harrison Ford returns to Deckard fully engaged and more quietly emotive than ever, while Ana de Armas’ lovely, layered work fuels some of the year’s most powerful sequences – but the true star here is cinematographer Roger Deakins, who crafts his greatest visual masterpiece to date. From start to finish, 2049 is filled with images that I simply cannot believe exist, whether in large and obvious moments like the crashing waves in the sea wall climax, or in small and intimate ones like K’s encounter with the woman who creates Replicant memories. No matter the scale, Deakins always finds the most elegant and striking way to build the image, without ever resting on easy visual signifiers or aesthetic nostalgia from the original. Combined with Hans Zimmer and Benjamin Wallfisch’s stunning score, which faithfully recreates the texture of Vangelis’ original work while greatly expanding it across this wondrous new visual palette, Blade Runner 2049 is a mesmerizing aesthetic experience with real heart and intelligence at its core. Its greatest similarity with the original might be the sensation one feels while watching it, like one has wandered into a long, haunting, and revealing dream. Blade Runner was one of the singular science-fiction accomplishments of its age, and 35 years later, Blade Runner 2049 is one of the true genre masterworks of ours.

Blade Runner 2049 is now available on digital download, and will release on Blu-ray and DVD on January 16th.

5. Call Me by Your Name

Directed by Luca Guadagnino

Desire is one of those impossibly complicated emotions that is hard to describe, harder to write about, and harder still to capture in a visual medium – which is why Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name is such an immensely remarkable accomplishment. The film chronicles one summer in the life of a teenage boy, Elio – played with a perfect degree of precocious, performative confidence by 2017’s busiest young actor, Timothée Chalamet – living in Italy with his parents. His academic father (Michael Stuhlbarg, also incredibly busy this year, and who gives the film’s best performance in a single gut-punch of parental warmth near the end) takes on a graduate student every year as an assistant, and when Oliver (Armie Hammer, who has never been better or more effectively used on screen) arrives, Elio is drawn to him for reasons he cannot initially understand or express.

Elio and Oliver slowly fall in love, or at least a deep sense of passion, and how the film builds that sense of desire, gradually and carefully and realistically, over the course of two hours feels quietly revolutionary, not just for gay cinema but frankly for all kinds of films and all manner of relationships. The emotional and physical vulnerability the film expresses, primarily through performance and aesthetics, renders the complicated feelings of its main character for the audience to not just witness or perceive, but to feel as a genuine part of themselves. It reveals things about the awakening of sexuality and desire we may have forgotten in ourselves, or never truly grappled with in the first place, wherever we may fall on the spectrum of orientation, and belongs to that rarified class of films that perfectly captures a complicated but fundamental human emotion.

Shot by Thai cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, every frame of Call Me by Your Name is a work of art, a painting of light and color and texture, with incredible-yet-subtle compositions that consistently convey so much about the landscape, these characters, and how those forces interact. Its focus on structures – of architecture, of water, of human bodies – is exquisite, and expresses so much about how Elio senses and experiences desire and longing. The camera is still but precise, like the films of Yasujiro Ozu or Satyajit Ray, that stillness consistently revealing endless layers of visual depth. Based on a 2007 novel by André Aciman, the film is deep and rich in novelistic fashion, not through a concentration of verbal detail, but through a richness of sensory depth. As a work of visual art, Call Me by Your Name is a superb and singular achievement, culminating in a profound, long, startlingly simple final shot that conveys an entire emotional journey without a single word.

Call Me by Your Name is now playing in theatres in limited release.

4. A Ghost Story

Directed by David Lowery

While there are plenty of films, horror or otherwise, about the living being haunted by the dead, David Lowery’s A Ghost Story is the only film I’ve ever seen about the dead being haunted by the living – specifically, by the sad mundanity of grief, by the cruel and quiet passage of time, by the way the world continues to spin and slowly move on through innumerable changes. A married couple, played by Casey Affleck and Rooney Mara, have just bought a new house together and are planning to start the next phase of their lives when the husband dies in a car accident – and in what feels like a crazy cinematic dare gone horribly right, the husband rises from the morgue table, the sheet still over him, and remains under that sheet, with two eye holes crudely cut out, for the rest of the film, a child’s conception of a ghost turned into one of the most hauntingly beautiful images imaginable.

The film plays out as a series of long, still takes, every shot a little work of art in and of itself, with a precisely composed frame and a small series of actions that tells a story or conveys a mood. In one of the most memorable images, Mara’s character sits on the floor eating a pie a friend left after the husband has died. Mara sits in the middle of the frame, resting against a row of cabinets that extend past the frame’s boundary in a slanted line; a mysterious light, one of the film’s central visual motifs, dances on her legs, while Affleck’s ghost stands still at the back of the room, to the right; another room stretches out behind them, the bathroom in the far back. Mara eats the pie, and quietly cries, because she needs to eat, and she needs to cry, and there’s nothing else to do, and she probably feels confused and guilty the world hasn’t stopped around her. The shot plays out at extreme length; like many of the film’s images, duration is the key. The film demands something of the viewer when presenting such long, relatively still images, an engagement with space, depth, performance, empathy, memory, and more. This one in particular almost plays out like an art installation, as though you could come in and out and study it non-sequentially (though that would of course be doing the film a disservice).

This is perhaps the best image in the film, a moment that would have A Ghost Story rise this high in my Top 10 all on its own, but the entire movie is built out of similarly quiet, conceptual sequences, save for a digression with a house party and an amateur philosopher that breaks the film’s silence and unnecessarily verbalizes themes the extraordinary visuals make perfectly clear on their own. Cut that out or replace it, and I might call A Ghost Story a perfect movie. But perfection, of course, is not necessary for greatness, and A Ghost Story is one of the best and most aesthetically profound meditations on loss, time, transience, and space I have ever seen. While its style is clearly influenced by Eastern directors of the 90s and 00s like Edward Yang, Hou Hsaio-Hsien, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Lowery and cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo have accomplished something special and singular here, a poignant and unique achievement in the annals of American independent cinema that will be studied, discovered, and loved for many years to come.

A Ghost Story is now available on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download.

3. Personal Shopper

Directed by Olivier Assayas

Rarely has a film’s title described so little of its actual content. Olivier Assayas has an awful lot on his mind here: Consumer culture, fashion, body image, wealth and envy, cultural displacement, and how technology affects our psyche and relationships – and that’s before you get to the meditations on grief, the afterlife, and communicating with the dead. Assayas doesn’t seem to care much about how he weaves it all together, so long as it feels honest and engaged along the way, and the result is a film amazingly, refreshingly liberated from structural convention. It can feel like several different films in one, almost like a collection of shorts or vignettes, but every image and idea flows together so freely, are all so beautifully connected by Kristen Stewart’s commandingly naturalistic lead performance, that it all feels of a piece no matter how strange or seemingly disparate things become.

Pound for pound and scene for scene, Personal Shopper is as entertaining, provocative, and intoxicating a film as I’ve seen this year, separated by a hair’s breadth from the films ranked above. Two sequences in particular are burned into my mind as standouts. The first is a long series of scenes in which Stewart’s character, Maureen, takes a train to London to buy clothes for her boss, and throughout the day finds herself embroiled in a strange, meandering text message conversation with a mysterious stranger. It is perhaps the most exciting and engaging sequence on film this year, almost entirely devoid of music or verbal dialogue, tracing an entire emotional journey through a series of iPhone messages. In the second, she returns to her boss Kyra’s apartment and, at the mysterious texter’s urging, tries on some of Kyra’s clothes. This sequence is contained almost entirely in one long, fluid shot, a technique the film makes frequent use of, with a physically and emotionally naked Stewart driving the movement and attention of the camera as Maureen examines and transforms her body in the forbidden wardrobe she’s built for her wealthy employer.

The X-factor in all of this is Stewart, who gives what is to me the best performance by an actress this year. In the midst of a film with so much on its mind, Stewart’s work is thoroughly, inescapably human, full of rough edges, vulnerability, and quiet emotional strength. It is a performance so complete and enveloping – in every word she speaks, in every silence she leaves, in every inch of her body language – that it even extends to her thumbs; in the many text message scenes, she manages to convey volumes in how she types, mistypes, or even just hovers over the keyboard. She is the fuel that brings this entire wonderful oddity of a film to life, and between this and 2014’s Clouds of Sils Maria, it is clear that Stewart and Assayas actively make each other better when they collaborate. I hope they continue to do so for years to come.

Personal Shopper is now available on Blu-ray and DVD from the Criterion Collection.

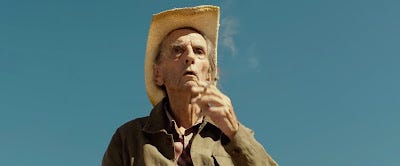

2. Lucky

Directed by John Carroll Lynch

Lucky is a film that is wise, powerful, and insightful far beyond the confines of its brisk 86 minutes, and the fact that you’ve probably never heard of it is an absolute shame. The last film to star the great Harry Dean Stanton, who passed away shortly after its release, Lucky would be almost unbearably poignant even if Stanton were alive and well. For as a portrait of an elderly man in a small town confronting the reality of his own transience, the film is a lovely and evocative character study, rich in detail and even richer in empathy, steadily building to a series of small emotional crescendos that are among the most beautifully life-affirming moments I have ever seen on film. That Stanton’s on-screen body is itself a transient object now, gone from this world but vibrantly alive on screen, makes Lucky almost too powerful to endure.

Between this and his similarly soulful work on Twin Peaks: The Return, Stanton went out this year as high on top as an actor possibly can, and few performers will ever encounter a vehicle as tailor made for them as this one is for him. It is a remarkable, vulnerable, utterly and completely lived-in performance, one that barely even looks like acting, though of course it is. Stanton was the kind of actor who could break your heart or make your day in a single glance, and he does both of those and everything in between many times over through the course of Lucky. It is not mere sentimentality that leads me to proclaim his work is the best by a male actor in 2017; when the Academy Awards inevitably fail to give him a posthumous nomination next month, it will be a major miss. But the work still stands, and it stands gloriously tall.

Speaking of Twin Peaks, David Lynch himself co-stars here as Howard, a friend of Lucky’s who has lost his pet tortoise, and the three monologues Lynch delivers about his beloved pet, which mirror and complement Lucky’s own arc of discovering and embracing the truth of impermanence, are three of the year’s most unforgettable, emotionally potent moments. Director John Carroll Lynch has no blood relation to that beloved filmmaker, but Lucky clearly has a lot of David’s DNA, in the sheer amount of authenticity and empathy the film displays for the locations, textures, and inhabitants of the American Midwest, with a quiet absurdist streak that plays as deeply poignant and completely true. The film is beautifully shot, conveying so much in how it frames the characters within their warm, earthy environment, and every supporting performance is full of natural warmth. This is the rare kind of film that can leave you with a markedly different perspective on the world and your own place within it by the time it is done, a work of art that looks at change, age, and death and comes out the other side finding hope and transcendence in the mundane. It is one of the great American films, and if this list inspires even one person to experience it for themselves, little would make me happier.

Lucky will be released on DVD and digital download on January 2nd.

1. Lady Bird

Directed by Greta Gerwig

This is probably something you’re not supposed to admit as a critic, but I think Lady Bird is a film I fell in love with before I’d even seen it. The quality of most great films is evident in any of their component parts, and from the moment I saw the trailer I had a feeling that Lady Bird would not only be something I’d love, but that it might be one of my very favorite kinds of films: A movie about ordinary people moving through mundane moments of transformation, made with wit and empathy and a singularly insightful voice. I loved the idea of it, loved that it was the solo directorial debut of the wonderful Greta Gerwig – who has starred in several of those kinds of movies, including Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha – and by the time it finally arrived in Denver, I was as excited to see it as I was the new Star Wars.

One scene in, that love was confirmed, as Gerwig, Saoirse Ronan, and Laurie Metcalf had already delivered one of the most effortlessly human moments I’d ever seen on film, turning on a dime from a beautiful instant of mother/daughter bonding on a car trip to the two arguing over something completely trivial, and then arguing about something far more fundamental. And by the time the credits rolled and the lights went up 90 minutes later, I was a raw and blubbering mess, feeling like the waterworks could break harder any second. “Lady Bird is, I can already say, one of my very favorite films I have ever seen,” I wrote on Twitter. “It is beautifully, hilariously, achingly, relentlessly human. I have rarely felt so much watching one movie.”

This is a film I love literally everything about, deeply and abidingly and completely. I love the entire tenor of the film, how Gerwig’s dialogue has a similarly distinctive snap and punch as an Aaron Sorkin or Quentin Tarantino, but aimed at everyday human and familial interactions, which just makes every word all the more resonant. I love the specificity of the setting, how lived-in Lady Bird’s Catholic school and Sacramento home town feels, as though we have stepped into someone’s life – or, more accurately, their memories. I love how impossibly rich in detail the film is, in every character and the space between them, reminiscent of Wes Anderson’s worlds in all their playfulness and lightness of step, but with much of the artifice and aesthetic distance stripped away. I love each and every performance, no matter how large or small, and how even a character actor in a relatively minor part, like the wonderful Stephen Henderson, can just slay in a few short minutes of screentime.

I love how the film manages to express the totality of the many highs and lows of an entire year in a young person’s life in just 90 minutes, and how easily the film makes me vacillate between smiles, tears, and laughter. I love the texture and color of Sam Levy’s cinematography, those warm rosy tones looking like they stem organically from the faded red dye in Lady Bird’s auburn hair that sits at the center of most frames. I love the subtle undercurrent of characters around Lady Bird struggling with depression, and how that’s set against the backdrop of America gradually losing its mind in the early days of the Iraq War, and how that mirrors our current moment of national grief and confusion without ever having to draw a solid line. And I love that the film has such deep empathy for the personality and desires of its main character that one of the most triumphant and jubilant moments on film in 2017 is Lady Bird getting a wait-list letter for a second-choice college.

I especially love every scene between Lady Bird and her mother, Marion, and how the tension between them feels so raw and so real, because it is so grounded in love. It is a love apparent in every word of their bickering, a love that makes Marion far too demanding of her only daughter and Lady Bird far too sensitive to her mother’s unintentionally hurtful jabs. It is a love that Ronan and Metcalf wear so beautifully on the sleeves of their performances, in those little moments between verbal spars where they look hurt or longing when the other isn’t looking, and which feels like the most radiant thing in the world on those rare occasions when mother and daughter leave all the baggage behind and just enjoy each other’s company. It is a love that allows a film so consistently and abundantly great to somehow find an even deeper, richer gear for its final scenes, a series of emotional crescendos that culminate in a moment that should by all rights win Metcalf an Oscar, and gives Ronan a soaring, simple, gorgeously evocative piece of writing to close out the film.

The primary thing I am drawn to in all kinds of art is what a work can discover, pinpoint, and reveal about our own humanity, and for me, no film this year did that more than Lady Bird. Greta Gerwig was already one of our great cinematic talents before making this film, and in these 90 minutes she establishes herself as one of the most singular and essential American filmmakers working today. I cannot wait to see what she does next. I am sure I will love it, just as I was sure Lady Bird would be something special. I could not love this movie any more if I tried, and I could not be happier to call it the best film of 2017.

Lady Bird is now playing in theatres in limited release.

Listen to the audio version of this list, released as a bonus episode of The Weekly Stuff Podcast, below:

Download the audio version of this list as an MP3.

Subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast!

Follow author Jonathan Lack on Twitter.