A Silent Dream of Sexual Cacophony: Psychoanalyzing E. A. Dupont’s VARIETÉ – Part Three: The Ménage-a-trois

Movie of the Week #28, Part 3 of 4

For this week’s Movie of the Week, we’re doing something a little different, covering one movie, but over four days. The film is E.A. Dupont’s Varieté, from 1925, and instead of a ‘review,’ we shall be reading a very peculiar essay I wrote in graduate school, for a class on Psychoanalysis and cinema. It is presented in the form of 4 letters from my alter-ego, Dr. Johnathon R. Black, to a fictive colleague, Dr. Reginald G. Winterbottom.

If you need to catch up, you may read The First Letter here, and The Second Letter here. Today, we continue with The Third Letter. Enjoy…

The Third Letter: The Ménage-a-trois

From the desk of Dr. Johnathon R. Black

The Thirteenth of Ventôse, Year CCXXVI

(Editor’s Note: March 3rd, 2019)

To Dr. Reginald G. Winterbottom,

The University of Edinburgh

Office 769

57 George Square

Edinburgh

EH8 9JU, Scotland

“There must be a voice within us that is ready to acknowledge the compelling force of fate in Oedipus … His fate moves us only because it could have been our own as well, because at our birth the oracle pronounced the same curse upon us as it did on him. It was perhaps ordained that we should all of us turn our first sexual impulses towards our mother, our first hatred and violent wishes against our father. Our dreams convince us of it.

— Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Berlin makes strange bedfellows these days. Some people have one people. Some have two. Some, even…

— The MC, Cabaret (1972, Dir. Bob Fosse)

My Dear Dr. Winterbottom,

It has been some time since last I wrote, the New Year’s Holiday having come and gone without my mailbox receiving a reply from your hand. It is quite odd, my dear Reginald, not to hear your prompt response on one of our mutual intellectual pursuits, so I have posted this latest letter to your office at the University, where I know you will have returned, by now, to your instruction, and your ever-ongoing studies. March has, as they say, come in like a lion, and so I attack my intellectual pursuits with similar gusto, in continuing my trek through Mr. E.A. Dupont’s dynamic, distressingly erotic masterpiece.

For if Varieté is indeed the cinematic dream I have, in my prior letters, cast it to be, then its substance – its manifest content – can and should be read symbolically. Its visual and narrative material, seen through this lens as distorted productions of the dream process, should withstand the rigor of analysis, whereby we may decipher the latent content from which blossoms the underlying meaning. Already, in my letter from December, I have performed some of the simpler work, such as reading the prison of the in medias res opening as a rather obvious distortion of the repressed guilt weighing upon Number 28, or interpreting the rolling of a stocking upon a feminine leg as the outfitting of a penis with a condom (which points us, invariably, towards sexual intercourse).

The most significant of these symbolic dream-distortions sits next atop our analyst’s docket, and in fact marks the moment I first experienced the film as a dream, when at last I awoke from my impromptu hibernation, blinking away the sandman’s traces to see the most wondrous of sights: an abstract world of eerie glowing lights, a sea of people transfixed in wonderment, and a camera frame swinging freely between them, acrobatically embodied to instill in the viewer a vicarious weightlessness.

I write now, of course, of the film’s centerpiece spectacles of trapeze artistry – arguably the heart of Varieté, and inarguably its most infamous visual material, even across the decades when the film languished in butchered, incomplete obscurity.(*) These set-pieces, in which the film’s central trio take to the air in the cavernous Wintergarten Theatre to perform such elaborate acrobatics play, to my eye, as an elaborate dream distortion of a tripartite sexual encounter. Mr. Freund’s camera, perhaps never more alive across the whole of his illustrious career than it is here, swings on high alongside the performers, miraculously freed from the tendrils of gravity to inhabit their field of wondrous vision. On any size screen, from the small television of my home to the vast cinematic canvas of the Englert where I was first exposed to the film last October, the experience is nigh overwhelming, a procession of cuts and camera movements so sensuously all-enveloping I find myself reaching for some nonexistent Dramamine whenever I gaze upon it – while also feeling thoroughly, uncontrollably excited, deep within my core.

(*) You see, my dear friend, that upon its release in these United States, a tragedy occurred. Varieté was edited drastically, and not presented in full for home viewing until quite recently, in the German restoration presented on DVD and Blu-ray here in North America by Kino Video in 2017. In that earlier bit of butchery, the entire first act – depicting The Boss’ family life, first encounter with The Strange Girl, and eventual choice to run away with his new mistress – was made absent, meaning the majority of content analyzed in my previous letters was inexcusably excised from the extant prints. A crime, perhaps even an assault, you shall surely agree. The film was thus robbed of much of its power and, indeed, denied a reputation that would properly place it alongside the other German Expressionist greats of the era. Perhaps, if these letters of mine ever see the light of day, we might endeavor to change that popular understanding.

A sexual act shot plainly from a few predetermined angles may be moderately arousing, as the proliferation of pornography can attest, but Mr. Freund here proves a hypothesis which you and I have afore debated: that an act seemingly devoid of sexuality, at least on its surface-most layer, can produce a profound excitation, if the act is performed with passion and, more importantly, if the camera – the eyes of the viewer – is embodied as an active, corporeal participant in the action.

Here we have three people, two of them already lovers, passing their bodies between each other, trading grips of the hands, communally swaying through the air in an act of physical exercise and exhibition experienced as a unit, a singular sensation shared across multiple bodies – and we, in the audience, do not merely see this experience, but, through its aesthetic embodiment, feel it, almost to the point of being an active participant in this airborne threesome. The sequence’s sensory nature tells us more about its foundational meaning than can be found in its literal, descriptive material, and thus the manifest content of aerial acrobatics gives way to an understanding of its latent core: the sexuality of the ménage-a-trois.

The film itself turns out to be a remarkably helpful dream in this regard, helping us to connect the dots of our analysis early on. Before The Strange Girl enters The Boss’ perverted gaze, it is established for us that his marriage is dull and sexless, information conveyed through the same form of symbolic distortion my letters have heretofore observed. When The Boss, wistful and dissatisfied, attempts to flirt with his spouse over dinner, he invokes a very specific memory. “Isn’t this a boring life?” he ponders. “Do you remember the old days, when we would do our trapeze act?”

Thus, the act of trapeze artistry is connected to youth, to virility, to happier, more fulfilling times – and, in short, to sexuality. “Do you want to break your legs again, and spend another year in the hospital?” the wife retorts, shutting the door on his sexual overture by questioning his ability to perform. As the husband argues, saying it could be done, that he is healthy, that he could in fact ‘get it up’ (into the air), his hands toy restlessly with a small glass salt shaker, twisting and turning this miniature phallus amidst his fingers, knowing the real thing shall not come out tonight. The trapeze act and the sexual fulfillment The Boss apparently craves are one and the same, the former standing in for the latter, its space of acrobatic performance mediating the same angsts and desires found in the bedroom.

It is for this reason that, after escaping together for Berlin, The Boss returns to the trapeze with The Strange Girl as his new partner, and why it is so significant that a third party be added to their aerodynamic exchange when Artinelli comes calling. Where there briefly were two players on this stage of carnal desires, now there are three, all involved in a conjoined, nebulously defined relationship constructed upon the forces of eroticism, competition, and violence.

Psychoanalysis tells us that this stage’s foundations are faulty, that its edifice is doomed to collapse, for within one of the discipline’s most elemental conceptions lies the truism that three is, indeed, a crowd. A ménage-a-trois of sorts is, after all, at the heart of Dr. Freud’s thinking, the pyramidal grouping of the mother, the father, and the son (the daughter, alas, is forgotten entirely – one wonders how Anna turned out so seemingly well-adjusted!) situated at the center of the Oedipal myth he so lovingly embraced.

And in this myth, as in Dr. Freud’s philosophy, there can ultimately only be two: For the mother to be possessed, the father must be vanquished, thus restoring a semblance of heteronormativity. Genuine polyamory – the kind to which much of your field research has been devoted these many years – does not exist in Dr. Freud’s conception; its stability cannot be upheld when the psychical tensions at play rely so heavily on competition and possession. Neither can the fact that genuine polyamory must, by definition, include some degree of defiance from the heteronormative order be accounted for in classical psychoanalysis, wherein homosexuality is described as a psychical defect, the result of a fault in the actualization of the Oedipal complex (here is where you and I depart quite sharply from Dr. Freud, the point at which the trains of our minds diverge down different tracks).

Nevertheless, it is within this well-trod Freudian framework that we see such dynamics operate in Varieté, where the ménage-a-trois, inherently fraught with Oedipal tension, cannot be maintained. Masculine control must be cemented, indeed created, by either a symbolic or literal destruction of the triangle’s opposing male, thus leaving only a line – which is itself a phallic shape – between the two remaining heteronormative dots.

Artinelli is the first to make his move, in a sequence of horrifying assault that reveals the fully abject darkness that lies within the masculine desire to possess the gaze. Luring The Strange Girl into his hotel room, all the while smoking from a magnificently phallic oversized pipe, Artinelli compels her to shut the door as she enters, locking herself inside this mysterious tempter’s space, her visage consumed by a quiet struggle between attraction and terror. All the sinister hallmarks of masculine sexual violence are visible in the scene that follows, including a claim of deserved gratification –“if it weren’t for me, you’d still be on the fairgrounds,”Artinelli manipulatively reasons – and a forceful display of sexual dominance exposing Artinelli’s need to claim physical ownership over his pleasure object. The dark culmination of scopophilic obsession is thus made manifest, as The Strange Girl, treated for so long by all men in the film as an object unto which desires are displaced, is now abused like an object as well.

Over the course of this trilateral tryst, The Strange Girl’s body shall become a battleground for these two men, a fetishized object upon which this carnal cold war unfolds. One evening at dinner, Artinelli invites The Boss to a lavish party, and when The Boss declines, The Girl, now fully entranced by her monstrous new suitor, begins stealing seductive glances with Artinelli (though what other kinds of glances are there?). While sucking slowly on a very phallic spoon – as all spoons are, you have at times reminded me – she goads The Boss into suggesting she attend instead, convincing her first lover to unwittingly relinquish his possession of her for the evening. The imagery of the ensuing festivities is scarcely in need of expert analysis, for the fireworks which explode overhead – hand-colored in bursts of red and green, a la the films of that fantastic Frenchman, Georges Méliès – while Artinelli and The Girl passionately lock lips on the banks of the river could hardly be any less ejaculatory. Artinelli’s gifting unto the girl an ornate bracelet is of more immediate concern, as he consummates his newfound ownership over her by claiming, with this jeweled trophy, one of the limbs to which his rival so desperately clings.

Back in The Boss’s room, darkly overcast with the shadows of doubt, his physical surroundings are once more transmogrified into an exteriorization of his deeply troubled psyche. The absence of The Girl from her bed consumes his waking thoughts. Overwhelmed by the desolation of his manifested lust, he paces in gloom, gazing fixedly out the window, unable to think of anything but the fetishized pleasure-object he does not, in this instant, wholly control. When she returns to the room, back into his internal domain, he rushes to her side, grasping instinctively for – what else? – her arm. He is drawn magnetically towards it, across her bosom to the appendage bearing Artinelli’s talisman, hidden with feverish paranoia by The Girl just before he can happen upon it. Every component part of her body, especially her limbs, have been rendered but poles of power in the tug of war that is this violent ménage-a-trois.

Thus cuckolded by his fellow funambulist, The Boss is mocked in whispers by the patrons of the tavern to which he frequents. On a table in a corner, the other men have sketched into the surface a taunting cartoon, of Artinelli and The Strange Girl embraced, with The Boss, styled as a jealous, horned Satan figure, glaring cross-eyed from afar. When The Boss comes down for a game of poker, the other men try to hide their jesting graffiti, and what follows can only be described as a wonderful psychoanalytic dance. The hostelry becomes another distorted manifestation of the psyche, withholding a truth The Boss must surely know, somewhere far underground in the labyrinth of his neuroses, but cannot see, his repressive id shielding him from harm. All the funny little men moving in carefully choreographed patterns of concealment display to us a different psychical process, each designed to keep the cogs of repression turning. Eventually, however, they are all gone, and The Boss sees this buried truth for himself, plain as day, and the weight of it overwhelms his being. In one of the film’s most expressionistic twirls, the room begins to spin, faster and faster, Emil Jannings’ tortured, twitching face superimposed atop the cinematographic convulsions, until his fists break through the aesthetic cacophony, smashing to pieces the table what bore his shame.

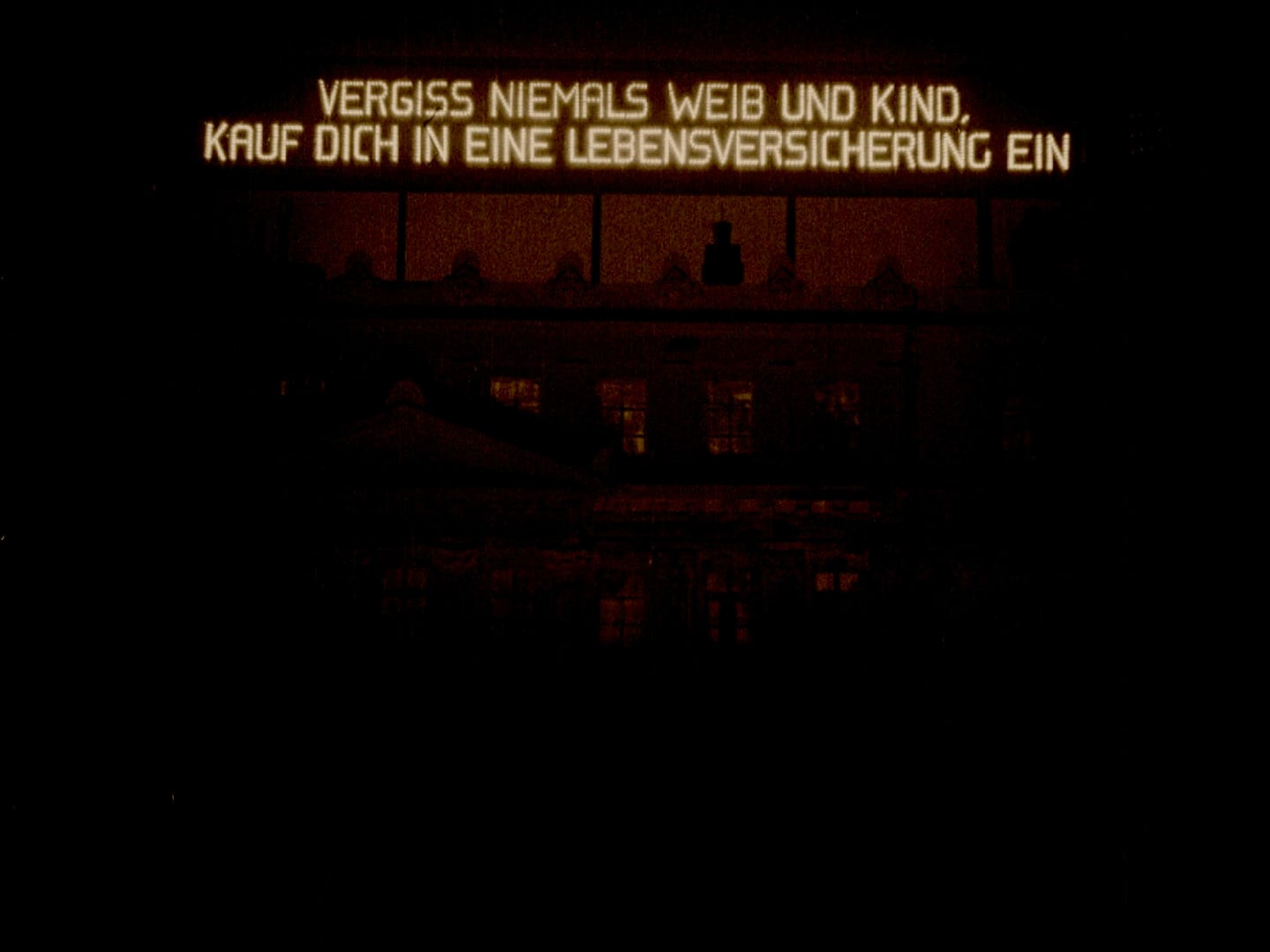

Waiting outside is the pièce de résistance, biding its time until The Boss lumbers into its savagely symbolic sight. For out on the street, high on an opposing building, flashes a brightly-lit sign, and as The Boss stumbles out in the haze of his sudden realization, it is illuminated with a thunderbolt of text: “Never forget your wife and child!” The words appear as though an act of God, or, more accurately, of The Boss’ own suppressed conscience screaming forth from the void. Frozen in his tracks, The Boss is nearly shamed into a position of penitence…until the second line of text appears.

“Never forget your wife and child … Buy into a life insurance.”

Hence the prospect of contrition congeals into the simmering passion of fury, and The Boss’ murderous intent, the eventual terminus of his and every other Oedipal figure’s destiny, having seen their possessive desiring threatened by a paternal combatant, is solidified. The conjoining spaces of fetishism and the ménage-a-trois having stood center-stage, the time has come for that last, most significant psychoanalytic apparatus to take command. There is but one question left to answer. Alas! It is the question of the phallus, a subject with which I know you are acquainted all too well.

But the hour grows late, and with so many months having passed since I last sent you mail, I am loathe to delay postage once again. Please tender your receipt of these letters as soon as you can, my dear friend! I wish to hear your thoughts, and moreover, to know you, your Mrs., and your many hounds are safe and sound. As the shadows loom long over my writing desk, my mind jumps to the darkest of conclusions, and wishes longingly for satiation!

Sincerely,

Dr. Johnathon R. Black

Tomorrow: The Fourth, and final, Letter, “The Phallus,” in which we discuss the greatest mystery of all…

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.