Director Spotlight Series: Takeshi Kitano #1 – “Violent Cop” and the dynamic character of violence

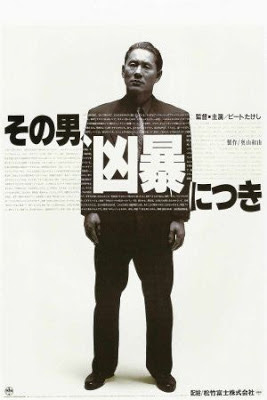

Welcome to Director Spotlight Series, an ongoing Fade to Lack feature in which we study the works of a notable filmmaker, movie by movie, for an extended period of time. Our first subject is renowned Japanese director Takeshi Kitano, one of my favorite filmmakers of all time and a fascinating artist who has never gotten enough attention from English-language critics. For the next 16 weeks, we shall explore his filmography in depth, moving chronologically to analyze one film every week. We begin with his wonderful 1989 debut feature, Violent Cop (Sono otoko, kyōbō ni tsuki – “That man, being violent” in the original Japanese). Enjoy!

Before getting started, a quick note on availability: The films of Takeshi Kitano are, by and large, currently unavailable in the United States. Most of his films have seen DVD releases here, but many of those were in absolutely horrendous, unwatchable quality, and are now out of print. Violent Cop falls into this category. The easiest way to access the film in North America at present time is to stream it on Hulu; the quality is pretty rough, but watchable, although there are, unfortunately, ad-breaks that interrupt the experience. But for those seriously interested in this and other Kitano films, I would recommend importing a DVD from abroad. The best in-print DVD release of the film is Second Sight’s Region 2 UK edition, available from Amazon UK. You will need a region-free DVD player to watch it, but the quality is quite good, featuring proper color-timing and anamorphic widescreen, and it contains an informative hour-long documentary on Kitano’s career.

Without further ado, begin reading my analysis of Violent Cop after the jump...

Takeshi Kitano is an utterly singular director the world over, even in his home country of Japan where, despite being clearly influenced by great and popular filmmakers like Yasujirō Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, and Kinji Fukasaku, it took several films and many years for his work to gain any measure of popular acceptance. While this was due in large part to his long history as a manzai comedian and beloved television personality – the Japanese public had difficulty accepting someone they knew so well for a particular, lighthearted persona as a ‘serious’ performer or director – it must also be considered how much Kitano’s films, stylistically understated yet thematically complex, ask of their audience, and how potentially alienating they are for many as a result.

I imagine his work is especially challenging for American viewers who, without a healthy knowledge of Japanese cinema, would likely be unaccustomed to many of his stylistic traits and narrative methods. Kitano minimizes dialogue, deemphasizes plot, naturalizes (or suppresses) emotion, paces to envelop, rather than propel, and edits using principles of discontinuity, in contrast to the basic, continuity-based language not only of American films, but Western cinema in general. His camerawork, too, is at once quieter and more expressive than the majority of mainstream American films, which rely less heavily on visuals to inform the viewer.

In short, it is likely many American viewers who encounter a Kitano film will be adjusting to an entirely different form of cinematic expression than they are used to. I do not believe this makes his work inaccessible – the learning curve is simply steeper, especially considering that there is no single film I can point to as the easiest place to start. Brother was made with American audiences in mind, but did not necessarily land as intended, and Hana-bi is probably his most ‘accessible’ film around the world (in part because it is his best), but I would nevertheless recommend that those interested in experiencing Kitano’s work start at the beginning, with Violent Cop, and work their way through chronologically. Not only is it fascinating to see his craft and worldview evolve over time – therefore lending viewers the best understanding of what his filmography says to us as a whole – but Violent Cop, while a dense and difficult picture in its own right, is a little easier to process than many of its successors – Boiling Point and A Scene at the Sea are particularly demanding – and a fantastic introduction to one of the richest and most rewarding careers in all of world cinema.

While many common stylistic elements of Kitano’s films are absent here, with others not yet fully formed, Violent Cop is an utterly confident debut picture, powerfully direct and uncompromising in its message, and bursting with cinematic talent and vitality at every single turn. Takeshi Kitano’s work in front of the camera, as protagonist Azuma, is a remarkably raw and powerfully physical piece of acting, just as three-dimensional, lived-in, and perceptive as his sharp directorial work. These are qualities that extend to every corner of the film, imbued in every shot, performance, and even the basic subtext and thematic foundations of the piece. An exploration of transgressive behavior in an intensely physical world, Violent Cop is a truly great film, and as a launching pad for the studies of violence, morality, duality, loyalty, society, institutionalism, nihilism, suicide, and death that would extend across much of Takeshi Kitano’s career, it is an endlessly impressive and invaluable starting point.

Casio Abe, author of the book Beat Takeshi vs Takeshi Kitano – the first and most significant critical analysis of Kitano’s dual career as actor/director, and one I shall refer to often in this series – begins his analysis of Violent Cop by describing and interpreting the first few scenes – surely one of the most shocking and impactful introductions I, for one, have ever seen in film – and arguing that they contain “everything that needs to be said about the film...” (50). “The condition of this film’s existence is woven together from the concept of time that has repeatedly been emphasized by such words as “persistence,” “continuity,” and “length,” together with the spatial concept of the “impact of the right angle”” (Abe 50). Indeed, as Abe credits Makato Shinozaki, author of the first scholarly article on Kitano’s films, as the “guide” to his analysis, I recognize Abe as my own, and have built in part my study of Violent Cop around the basic principles he identifies above (46). We shall examine all these structural and stylistic elements, along with several of my own identification, as they relate to the film’s depiction of violence, construction of character, and cinematic poetics.

Characteristics of Violence

“Nothing? You did nothing? Then I’ve done nothing.”

One of Takeshi Kitano’s defining traits as a filmmaker is his use of violence. Many of his films contain violent characters, like Yakuza or wayward police officers, and depict numerous violent actions. When Kitano employs violence, however, he almost never does so out of a shallow desire to ‘thrill.’ Violence is an idea in Kitano’s films as much as it is an action, and that idea is something he treats seriously and analytically throughout his career, even in works that are meant to be taken as pure entertainment, like Zatoichi or Outrage.

Yet Violent Cop remains his only movie, I would argue, where violence itself is the core subject and key point of thematic interest. The film is methodically constructed to present violence as something dynamic, a complex and multifaceted action – or, I might argue, state of being – that ultimately means very little, but can result in a variety of complications. More than any single human presence, violence is what this film characterizes, and we leave the film with a fuller and more holistic understanding of how violence manifests and perpetuates itself.

Violence is so integral to this film, in fact, that the core elements Abe identifies as forming the language of Violent Cop – “persistence,” “continuity,” “length,” and “the impact of the right angle” – are also key to the film’s depiction of violence (50). I would expand upon and slightly re-work Abe’s identifications for a more holistic understanding, characterizing the film’s violence as Senseless, Persistent, Physical, Continuous, and Reciprocal. As with Abe’s principles, these five characteristics each serve a dual purpose: They describe both the nature of the violence itself, and how the film is constructed. To put it another way, the film’s themes are perfectly mirrored in its structure, and visa versa – Violent Cop is a great movie because it is a tightly assembled one, where the filmmaking constantly draws our attention to subtext, and the meaning we derive, in turn, points us back towards the formal execution. Let us study these characteristics, point by point, so that we may better understand the way in which they operate.

First, that the violence is senseless. Though omnipresent, violence means little in this film. At no point can it be rationalized, except on occasion as an outpouring of emotional duress, confusion, or rage (usually brought on by previous violence). Nothing is ever shown to be gained through brutality, except further suffering, and never do the characters find any true sense of peace or catharsis by acting savagely.

The film begins with an action that can only be described as ‘senseless.’ A group of teenagers gang up on a weak, toothless homeless man as he eats dinner, beating on their victim until he passes out. By opening the film with this scene, Kitano immediately contextualizes violence as meaningless; there is absolutely no way for us to explain why these kids do what they do, nor any tangible value they appear to gain from it. Because of the film’s violent continuity – something we shall discuss momentarily – this opening may be viewed as a ‘trigger’ of sorts, the kick-off to all violence that follows (note that our introduction to Detective Azuma, also grounded in violence, is a direct extension of the teenagers’ actions). Since this introductory assault is senseless, everything that stems from it shall be as well.

Throughout the film, violence continually brings the characters to dead ends or undesirable circumstances. This is established as soon as Detective Azuma is summoned into the new police chief’s office, berated not only for beating on a kid, but foregoing the opportunity to save the homeless man for the sake of doing so. Already, it is clear that when Azuma turns to violence, nothing comes of it. His next violent action is to punch and kick a belligerent pimp being detained in the hallway, which results in no further information or compliance.

The closest any character comes to gaining something from violence is in Azuma’s iconic interrogation of drug dealer Hashizume in a nightclub bathroom, where he slaps the man, over and over again, until Hashizume gives him a name. Azuma gets information – his best friend, Iwaki, is working for drug dealers – but this is only a temporary misdirection as to the effectiveness of violence, for both Azuma and the audience. Following up on the lead only tempts drug lord Nito to order Kiyohiro, the main antagonist, to murder Iwaki, among others (including Hashizume); ultimately, violence is directed back upon Azuma for his meddling. Nothing good comes of Hashizume’s information. The drug trade isn’t even interrupted, and many, many people are eventually killed, including Azuma, Kiyohiro, and Nito.

From the slapping interrogation onwards, we see a clear shift in how the senselessness of violence is portrayed, moving away from having no effect to being directly harmful to the person perpetrating the violence. Violence becomes directly reciprocal, a characteristic we shall cover in greater depth later. For now, it is most important to note that all the narrative action of the film ultimately leads to a ‘senseless’ resolution, wherein the majority of the main characters are killed, new participants take their place, and things go on as they had at the start. As a result, violence accomplishes absolutely nothing during the film, and is inherently senseless as a result. This is reflected in the film’s structure, where the actual plot is more or less meaningless. All the machinations between Azuma and the drug dealers is intentionally convoluted and unsatisfying, because it is fueled by violence. The narrative, therefore, is senseless, and because its subject is violence, the film makes us aware that nothing particularly good can come of following this story. In this way, Violent Cop can also be called reflexive.

The second characteristic of violence is that it is persistent, which is a fairly simple and obvious observation to make, given that the film itself is intentionally repetitive. Just as Azuma always follows one kick with multiple kicks – keeping the boy in the opening sequence down on the ground every time he tries to get up, for instance – or one slap with dozens more, the film has a relatively small vocabulary of physical motions – kicking, slapping, punching, stabbing, walking, and running – it repeats in a variety of contexts. Both Azuma and Kiyohiro kick people to the ground and continue to kick them persistently (a violent motion originated by the teenagers in the opening scene); Azuma slaps not only Hashizume, but Kiyohiro and the boy at the beginning; Azuma and Kiyohiro both use persistent punches on each other, though the most obvious use of punching is Nito on Kiyohiro, who lets loose on his subordinate with what Abe notes to be a revealing ferocity; Kiyohiro is introduced stabbing a man over and over, and later does the same to Azuma, who returns the repetitive motion to save his own life (53). Particular scenes and scenarios too are repeated with a rhythmic persistence: Azuma is berated by the police chief for going too far multiple times, as is Kiyohiro by Nito when he unnecessarily murders Hashizume. Similarly, Azuma points a gun at Kiyohiro’s head after savagely beating his nemesis in the locker room, and Kiyohiro repeats the gesture in the alleyway, also after severely wounding his rival.

But the most notable repetitive element, of course, is walking. The human body in forward motion is a fundamental visual motif repeated time and time again over the course of the film, and sometimes manifests itself as part of the violence (such as the final confrontation, when Azuma walks towards Kiyohiro to shoot him, while being shot himself). The persistence of walking is crucial for many reasons, not least of which because it underlines the film’s third characteristic of violence: Physicality.

One cannot ignore how intensely physical a film Violent Cop is. Every motion I have described so far, and every additional act of violence in the film, is predicated on physicality, making use of hands or feet. Even stabbing is a physical motion, the knife becoming an extension of the wielder’s arm, which is why we see many blades in the film, but far fewer guns. There is little physical motion involved in using a gun, so on the one occasion a gun goes off and has impact – the bystander being killed at the movie theatre during Azuma and Kiyohiro’s stand-off – it is because of a major physical movement (Azuma kicking Kiyohiro’s gun in a different direction).

The film’s most impressive and elaborate set-piece, where Azuma, his young partner Kikuchi, and several other officers chase a drug addict, is a stirring high-point because it is based entirely around compelling depictions of physicality. The criminal beats the officers with an instinctual, animalistic ferocity when they come to his door, and when he escapes and begins to grapple with the officer waiting on the street, a slow, Jazz-piano piece swells in, all other sound is dropped, and the camera begins to capture in slow-motion. All of this serves to direct our full attention to the physical nature of the fight, to the way these bodies move and how their expressions of violence are tied so closely to their physical presence. While the motion and sound snap back into place when the criminal hits the officer with the bat, we have now been made acutely aware of violence in relation to physicality, and pay attention to it for the rest of the chase. Considering this, we can say that the film itself favors aesthetics that highlight the physical presence; the aforementioned dropping of diegetic sound for music (the Jazz piece continues through the entire chase as counterpoint), as well as camera shots from Azuma’s point of view as he chases the criminal, bobbing up and down in motion with him.

Most significantly, Kitano’s trademark, minimalistic dialogue seems to develop here as a way to force viewers to focus on physicality. Kitano wants us to learn about these characters by observing their bodies – including the movements of their limbs, expressions of their faces, and particular ways they hold themselves – rather than reveal them through speech, which is a simpler, less dynamic, and less honest way of developing personality. Kitano would push this particular idea much further in his following features – to the point where the characters he plays almost always speak even less than Azuma, and the protagonists of A Scene at the Sea are deaf and mute – even though Violent Cop remains his most intensely physical film on the whole.

But the most important physical depictions are, undoubtedly, the walking scenes. They are of particular fascination to Casio Abe, who devotes an entire page to describing Kitano’s walk, and all we may learn about his character (and the film) because of it. “We can decisively dissect the complicated structure of Takeshi’s walk,” he concludes, “because the scenes of him walking are repeated so many times” (53). Indeed, this goes back to the notion of persistence – Azuma walking is, as previously stated, the film’s most repetitious element – but underlines for the viewer how much the body matters to this film. Abe describes the persistent walk as Kitano showing “the subtle, bare nature of his own flesh,” and notes that many other characters are revealed through their individual forms of movement (53).

From a cinematic standpoint, what the walking – and, by extension, constant reminder of physicality – gives us is a continual sense of forward momentum. Abe says of Azuma that “he walks as if being propelled vigorously forward,” and that undeniable sense of propulsion one gets watching him walk is indicative of the overall thrust in the film’s pace, plotting, and depiction of violence. Like Azuma, Violent Cop is always in forward motion, with acts of violence seamlessly transitioning from one abuse to the next.

The violence, and the film, may therefore also be considered Continuous, our fourth and most important characteristic. Continuity – not just the ‘shot-reverse-shot’ mentality foundational in Western filmmaking, but the notion of every action directly setting up the next, and being rooted in one previously made – is the single most important element of Violent Cop, informing everything the film has to say and the way in which it is said. “The fact that the film’s running time qualifies it as a feature-length “entertainment film” despite the drastic pairing down of Hisashi Nozawa’s original screenplay,” Abe writes, “seems almost entirely due to the way that individual actions are “continued” in it. Depicting the persistence of violence through its “continuity” requires stripping violence down to its essence” (51).

Indeed, Violent Cop is constructed along lines of near-total continuity. I have already discussed certain violent acts that beget other violent acts – like the teenage gang beating the homeless man, leading to Azuma beating of one of the boys – but around the time Azuma interrogates Hashizume, we can trace every single moment of violence as part of a straight line, pointing toward the ultimate conclusion of death. Azuma learning of Iwaki’s corruption leads to Iwaki’s murder, which in turn makes Azuma more violent; Kiyohiro’s killing of Hashizume gets him punched repeatedly by Nito; Azuma arrests Kiyohiro after Iwaki’s death, beats the living daylights out of him, and nearly shoots him; in return, Kiyohiro kidnaps Azuma’s sister, has her gang-raped, and later stabs and nearly shoots Azuma in the movie theatre sequence (Azuma escapes by turning violence around on Kiyohiro once more); in response to all this, Azuma – no longer an officer – buys a gun illegally and goes on a spree, murdering Nito, Kiyohiro, and even his sister, before being killed himself by the man who watched him murder Nito.

In short, the film’s violence is propulsive, just like Azuma’s walk. One step leads to the next, and so on and so on. Kitano is making a commentary on how violence itself is continuous, never ending until all involved are dead and therefore unable to continue being violent. He does this by structuring his film around principles of continuity. While the plot may be a tad fuzzy on one’s first viewing, multiple watches reveal just how tightly constructed the movie is, and how clearly it indicates actions being ‘continued’ throughout. For example, after the teenage boys attack the homeless man, we get a lengthy, uninterrupted long shot on one of the boy’s houses. The boy enters from the left, walks inside, and closes the door; after a few seconds pass, Kitano walks in from the same direction, ‘continuing’ the motion of the boy (at a right angle, no less, as Abe would point out – right angles are another fundamental visual motif). There are many shots like this, and many less obvious, but no less powerful, examples of continuity editing and principles informing how we watch and process the movie.

This stands in stark contrast to Kitano’s typical ‘discontinuity,’ his primary form of cinematic language starting with Boiling Point which, as Abe notes, disperses rather than continues violence, and brought into full view with A Scene at the Sea, the first film he both directed and edited (73). We shall talk more about Kitano’s principles of discontinuity in the weeks to come, but for now, it is important to understand how continuity operates in Violent Cop, and how this gives way to the film’s fifth and final characteristic of violence: Reciprocity.

As previously noted when discussing the senseless nature of violence in the film, violent actions tend to beget equally violent reactions. Abe refers to this as “the transmission of violence,” which is a good way to phrase it (50). Azuma and Kiyohiro ratchet up their violence over the course of the film because they are in each other’s orbit, transferring increasingly brutal behavior back and forth to one another until they eventually arrive at mutual destruction. Even outside these two characters, though, violent reciprocity is omnipresent; closely connected to the characteristics of senselessness, persistence, and continuity, there are only a small number of occasions where violence is not returned upon the perpetrator. It may seem obvious – reciprocity is the principle behind any sort of fight, after all – but in characterizing the film’s violence, and what the film has to say about the toll brutality takes on the human body and spirit, it is important to note, and fundamental to the next part of this discussion.

If violence is reciprocal, after all, that raises another important set of questions about why people commit violence. Surely the characters are not all entirely unaware, at least subconsciously, that their actions may result in reactions. This is a reality of the film, and an inherent truth Kitano sees in violence, one that manifests itself through the dual character arcs of Azuma and Kiyohiro, and the central theme of suicide.

Mutually Assured Destruction

“Everybody’s crazy.”

Each of Takeshi Kitano’s first four films deals heavily, either directly or indirectly, with the notion of suicide. Like violence, Kitano is interested in exploring suicide not as a simple action, but a complex and dynamic idea that may take on multiple forms, as expressions of both personal and societal impulses.

“Violent Cop is unmistakably a film about suicide,” Abe notes, “although this fact is not as plainly stated as in Sonatine” (64). The latter film, which we will discuss in just a few short weeks, depicts suicide as deeply personal, stemming from within and resulting in actions directed at oneself, while Violent Cop, a less introspective film, illustrates suicide as a communal action, requiring others to be consummated.

Indeed, both Azuma and Kiyohiro, the two main characters, need and depend on one another to fulfill their suicidal impulses. This desire is not explicitly stated for either character, but observing that the violence they engage in is both continuous and, most importantly, reciprocal, they must each be aware – at least by the time of their final confrontation, and probably sooner – that acting violently toward the other will invariably result in being acted upon with equal brutality. Abe describes this unique form of suicide thusly:

The “degree of suicide” in those who commit criminal acts is increased when a crime can be said to require a high degree of gambling with one’s fate. In other words, anyone who knows that they will be discovered and punished for a crime and is still driven to commit it must, to some degree, be operating so as to “terminate oneself, the one who commits crimes.” This is another way of describing “suicide.” (64)

Azuma and Kiyohiro are inextricably linked, and drawn together with increasing force, because they share this particular type of suicidal impulse. Individually, each acts outside the boundaries of their chosen profession, knowing full well that each time they transgress, they will be reprimanded for it. In beating the teenager at the beginning, or running over the drug addict with the car, Azuma is clearly aware he shall be disciplined, yet does not seem to care – either the reaction he will bring upon himself means nothing to him, or he subconsciously yearns for it (a desire that will become increasingly ‘conscious’ as the film goes along). Similarly, Kiyohiro knows killing Hashizume is a transgressive action, but takes pleasure in it all the same; the pain he receives in return, as Nito punches him persistently, does not appear to phase him. Like Azuma, he either does not mind the reciprocal pain, or craves it as an expression of self-loathing.

Eventually, as the violence these men dish out ratchets up in ferocity, the reactions they expect to receive are similarly enlarged, to the point at which they attack one another with suicidal imagery. I previously noted how there is repetition in the way both Azuma and Kiyohiro briefly gain dominance over the other – Azuma beats Kiyohiro to the floor in the locker room, and Kiyohiro stabs Azuma to the ground in an alleyway – and what is most important to note in these scenes is the way the men point guns at one another. Azuma forces the barrel of his gun into Kiyohiro’s mouth, while Kiyohiro point his gun against Azuma’s head at a right angle (the angle of suicide, as Abe would tell us). Both motions are suicidal ones, used when a person directs a firearm towards oneself. But neither character ever puts a gun to their own head; they instead direct such suicidal motions at the other, asking for and welcoming these motions to be returned upon their own bodies.

Why these two men have arrived at such a complexly nihilistic point is never made clear. But looking at Azuma, the more developed of the two characters, we can see that this is a point he builds to, rather than one that is completely instilled in him from the very beginning. Azuma is, in fact, unique from most Kitano protagonists – at least those Kitano himself plays – as he has a clear arc of transformation, and is still ‘alive’ when we first meet him. Many Kitano characters, like Murakawa in Sonatine or Nishi in Hana-bi, already inhabit the ‘realm of death’ at the start of the film. Detective Azuma does not. While he has already started resorting to violence in many different situations – one of the funniest and most revealing sequences sees him persistently kicking and hitting the man who sleeps with his sister – he is still capable of displaying a variety of emotions. He is happy to talk about his sister, Akari, whom he clearly loves and feels protective towards (in part because she is mentally handicapped), and even enjoys spending time with. He laughs frequently, enjoys making fun of Kikuchi, and takes pleasure in going out to dinner or playing arcade games. The pleasures these activities bring him may be muted, but at the outset, he is not yet living merely for the sake of living.

But his transformative arc is already underway, which means even outside his violent outbursts, we see many hints of melancholy. This is manifested most clearly through carelessness: He is frequently insensitive towards others – especially Kikuchi, whom he takes money from several times – cares little about the rules (he gambles at the local diner), and only occasionally shows enthusiasm for police work (though as the chase sequence with the drug addict shows us, he can be completely engaged in his job under particular circumstances). Gradually, he is becoming increasingly disconnected from the world around him, and over the course of the film, he will shed every extraneous emotion until all he can feel, produce, or desire is violence.

Iwaki’s murder at Kiyohiro’s hands is the turning point for Azuma. It is implied Iwaki was Azuma’s only real friend, and having lost that friend on two levels – Iwaki does not just die, but is revealed to be corrupt – Azuma’s apathy increases tenfold. He gets less pleasure out of hanging out with Kikuchi, stops enjoying drinks and dinner, and distances himself from police work, channeling his energy instead into personal vendetta. Once violence completely overwhelms him, and he is removed from the force for illegally detaining and beating Kiyohiro, Azuma enters the realm of death, never to return. As Abe puts it, “with his sister abducted and no with no hope of her mental condition improving, there is nothing left to keep him from pouring all his passion into erasing all traces of himself” (66). Azuma buys a gun illegally, and in the proceeding murder spree – he kills Nito, Kiyohiro’s men, Kiyohiro, his sister, and is then killed by the man who witnessed Nito’s death – Azuma forcibly expunges all evidence of his own identity, existence, and significance from the earth. Through violence, he achieves total self-annihilation – suicide in the most extreme, if not purest, sense.

Kiyohiro is his double in this arc. Though they initially operate on opposite sides of the law, in the end, their ultimate goal – the destruction of the self – is the same, and they perpetuate their cycle of conflict not for any greater good or personal gain, but merely to arrive at death. “Many people define themselves by their enemies,” Abe writes, “but the senseless ways that enemies who are identical taunt each other in pursuit of mutual destruction can only be defined as “suicide”” (65). Of all the film’s characters, Kiyohiro vocalizes this theme most clearly when, in preparation for the final standoff, he tries forcing his cronies to stay and fight – “Either way, you’re going to die,” he tells them, a sentiment that is also directed inward – and kills the two that refuse, further removing all evidence of his existence.

The climactic confrontation between the two foes can be viewed as an inversion of the Western archetypal hero/villain standoff. Violent Cop technically builds to its conclusion along the same continuous lines as many Western stories – hero and villain learn about one another, hero makes sacrifices to get closer to the villain, hero barely wins in the last battle – but the lack of reward for Azuma – all he gets from killing Kiyohiro is a destroyed, dope-addicted sister – and immediate way in which he too is destroyed underlines that this conflict had no overriding goal, other than death, and absolutely nothing to do with good and evil. Azuma and Kiyohiro’s antagonism was an empty, hollow pursuit, a truth made clear when Nito’s subordinate, after killing Azuma, flips on the lights, illuminating the sheer emptiness of the warehouse space, the arcs of these characters, and the narrative thrust of the film itself (a ‘reset button,’ in essence, is hit in the following scene, when Nito’s secondary takes over the drug business, and Kikuchi steps into Iwaki’s corrupt shoes).

Violent Cop is ultimately empty, as it must be – this emptiness is core to the film’s profound exploration of violence.

Onwards!

It is clear, analyzing Violent Cop, that Takeshi Kitano’s directorial career began in much the same way as it would continue. While the story, themes, and character arcs play out a little differently than they might in later Kitano films, the ideas he explores here are ones he would continue developing for years to come. That the film’s discussions of violence and suicide do not seem any less mature in comparison to Kitano’s later works is astounding – the film remains a tremendous accomplishment to this day.

The last point I would make on the film is that, accepting a few small idiosyncrasies here and there, the cinematic elements of Violent Cop also arrive more or less fully formed. Much of what I love about Kitano’s style is present from the start, even with composer Joe Hisaishi a few years from coming on board, and Kitano yet to start editing his own work. I am especially fond of Kitano’s cinematography, provided here by Yasushi Sasakibara, which is calm, clear, and articulately composed from the very start. He moves the camera bit more than he would in future works, and the moving point-of-view shots during the chase scene are a little wonky and out of place, but the film’s imagery is so incredibly thoughtful, visually rich with setting, character, and detail. Kitano trusts the viewer to read his frames for meaning, and imbues them with volumes worth of significance (like the perpetual ‘right-angleness’ of the imagery and action Abe so often speaks of). This is not Kitano’s most visually remarkable work, but it is a wonderful start, and there are certain sequences that are constructed absolutely masterfully. I have already mentioned the chase sequence several times, but it bears repeating: That set-piece is a historically great piece of filmmaking, still the best ‘action’ sequence in Kitano’s whole filmography and one of the most understatedly thrilling scenes I have ever witnessed.

From Violent Cop, we now move on to Boiling Point, Kitano’s second film, and one of his most challenging (it, too, is streaming on Hulu, though this DVD is the best available version). It is also a favorite of mine, and one I very much look forward to discussing next week.

Next Week:

Our spotlight on Takeshi Kitano continues in

Boiling Point (3 – 4 X 10月, 1990)

Your turn – now that you have read my analysis, what thoughts do you have to share on Violent Cop? Please sound off in the comments, and come back next week to continue participating in the discussion!

Jonathan R. Lack is a film and television critic from Golden, Colorado. His book, Fade to Lack: A Critic’s Journey Through the World of Modern Film, is now available in paperback and for Kindle e-readers from Amazon. He can be followed on Twitter @JonathanLack.

Director Spotlight Series appears every Monday, exclusively at www.jonathanlack.com.

Copyright © 2013 Jonathan R. Lack. All rights reserved.