“The Hunger Games” Versus “Battle Royale” – A Critical Analysis of Two Similar Works: Act One – Comparing the Original Books

This Friday, the first big tent-pole release of 2012 hits theatres: “The Hunger Games,” an adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ 2008 smash-hit novel. I’m excited for the movie, as are many others, but here’s the thing….when I read the book, it felt awfully familiar. In fact, it was remarkably similar to one of my favorite books of all time, Koushun Takami’s “Battle Royale,” published in 1999.

So throughout this week, I’m publishing a special three-part article investigating whether or not Collins stole from Takami, and why that informs how we should look at “The Hunger Games.” You’re reading Act One, wherein I explain all the similarities between the two novels. Acts Two and Three will go up over the next two days – the Prologue, which explains this whole scenario, was posted yesterday.

So without further ado, enjoy Act One of “The Hunger Games” Vs. “Battle Royale” after the jump….

Jonathan Lack at the Movies Presents

“The Hunger Games”

Versus

“Battle Royale”

A Critical Analysis of Two Similar Works

Act One:

Rumble in the Jungle

Comparing “The Hunger Games” to “Battle Royale”

I am certainly not the first person on the Internet to point out similarities between “Hunger Games” and “Battle Royale.” The premises to the two stories are so very similar that it’s impossible not to have stumbled across this argument before, and whenever the issue arises, rabid “Hunger Games” fans immediately jump to Suzanne Collins’ defense, pointing out all the places she could have gotten inspiration from other than “Battle Royale.” Typically, they argue that Koushun Takami’s work is also derivative, citing comparisons between “Battle Royale” and “Lord of the Flies.” Both novels examine the breakdown of isolated societies using a cast of adolescent characters. Thus, if “Royale” can be called imitative, accusations of Collins’ plagiarism can be left by the wayside, and we can just say that she and Takami drew similar inspiration from similar works. Right?

Wrong. These arguments are silly and ill-informed, and should you come across such rhetoric, ignore it promptly, for it neglects many key facts. First, the “Lord of the Flies” comparison is a moot one; while “Battle Royale” shares certain thematic connections to William Golding’s classic, their plots and characters are largely dissimilar; Takami examines social breakdown very differently than Golding did, and it’s important to note that “Royale” comes out of a specific, contemporary Japanese context that further distances itself from Golding’s strong British voice. No matter what, isolation leading to social breakdown is a theme entrenched in many forms of literary tradition; if one wishes to call “Royale” derivative for this reason, one must be prepared to lodge the same criticism at “Flies,” which is of course ridiculous.

More importantly, this theme is the key place where “Hunger Games” and “Battle Royale” differ, for “Games” is not concerned with tracing a social collapse among its young characters. The participants in the deadly Hunger Games do not know each other, unlike the class in “Battle Royale,” who have always been close, or the boys in “Flies,” who form bonds before falling apart; there is, therefore, no existing ‘society’ to watch collapse in “Games,” and with that theme missing, the book shares no substantive similarities with “Lord of the Flies.” It isn’t fair to enter Golding’s work into this particular discussion.

In addition to “Lord of the Flies,” many like to argue that “Battle Royale” and “The Hunger Games” also work in the tradition of Stephen King’s ‘Richard Bachmann’ pseudonym novels, “The Long Walk” and “The Running Man.” And yes, there are surface similarities between these books, as they all involve gruesome death contests; “Long Walk” in particular parallels “Games” and “Royale” in several crucial ways. But this simply isn’t sufficient evidence to say that Collins wasn’t inspired by Takami; one can’t ignore the extremely specific elements “Games” shares with “Battle Royale,” far outpacing any parallels found in the Bachmann novels.

And now it’s time for me to present my evidence: the countless, eerily precise places where “The Hunger Games” and “Battle Royale” match up. It’s more than just the identical premises; to my mind, at least, suspicious similarities pop up all over the place.

We’ll start with a series of bullet points, but before we begin, please keep in mind two things: First, I didn’t go into “The Hunger Games” looking for comparisons. I didn’t even know what the book was about, and it had been years since I read “Battle Royale.” That such similarities struck me at all speaks to how strongly they stand out. Second, I like “The Hunger Games.” I really do. I don’t think it’s a great book, but it is a fun page-turner, and I’m glad I read it. I don’t make these comparisons to disparage the quality of the book. A work can be plagiarized and good at the same time, and even then, there are imaginative bits to Collins’ novel I’m quite fond of. I am of the opinion that her work pales in comparison to “Battle Royale,” but we will get into such value judgments in the next section. For now, we’re only examining the facts, and they are as follows:

Similarities Between Books:

Chiefly, the premise, which is the strongest indicator of copying and absolutely cannot be ignored in this debate, no matter how much some fans would like to: “The Hunger Games” is about a dystopian future where the tyrannical government demonstrates its control over the people by hosting an annual event, the titular Hunger Games, where 24 children, aged twelve to eighteen, are randomly selected from across twelve districts to compete in a battle to the death, where participants are forced to kill one another until only one adolescent survives. “Battle Royale” is about a dystopian, alternate-history Japan where the tyrannical government demonstrates its control over the people by randomly selecting a class of 42 high school students, aged fifteen, to compete in a battle to the death, where participants are forced to kill one another until only one adolescent survives.

The titular Hunger Games were established in response to the districts of Panem rebelling against the government; in modern times, the Games are maintained to keep the public in line. While the history of the alternate-world Japan in “Battle Royale” is less clear, it is explicitly stated that the government runs the program to intimidate the public and maintain its fascist power. Kinji Fukasaku’s 2000 film adaptation of “Royale” is even closer to “Games” in this regard: in the movie, the program is initiated as a direct response to widespread student rebellion.

In both books, a lottery system is used to choose the ‘players’ (a literal “Bingo” style public lottery is used to selected individuals in “The Hunger Games,” while the government randomly selects whole classes of students in private in “Battle Royale”).

Katniss and Gale in "The Hunger Games" movie

The protagonist of “Battle Royale,” Shuya Nanahara, is close friends with a girl named Noriko Nakagawa; she has always had a crush on him, but he has never felt that way about her until they team up during the Battle. They fall in love over the course of the novel and ultimately wind up as the only two survivors of the Program. In “The Hunger Games,” one could argue that Noriko’s role is split in two between Gale Hawthorne, Katniss’ best friend from District 12, and Peeta Mellark, the other tribute to the Hunger Games from District 12. Gale fulfills the platonic, childhood friend side of Noriko’s character, while Peeta is the love interest (sort of…it’s way too complicated) and teammate during the carnage. Additionally, just as Shuya must care for Noriko after she is injured, Katniss must do the same for Peeta when she eventually finds him, and they are the only two survivors of the games (and though Katniss and Peeta don’t ‘get together’ in “The Hunger Games,” Wikipedia tells me they do in one of the book’s sequels). So in short, both books end with one boy and one girl, romantically linked, left alive in the end.

A man named Kinpato Sakamochi runs the Battle Royale program depicted in Takami’s novel, and is an effectively unsettling antagonist because of his casual enthusiasm for the slaughter; when telling the kids the rules, he acts like it’s just another day at school, and when he addresses all the players over the loudspeaker during the program, he’s cheerful. This disturbing disregard for the lives of children is found all over “The Hunger Games.” The most direct parallel to my mind is Effie Trinket, coordinator of the Games for Katniss’ home district; she runs the lottery for who will participate in the killing contest like it’s a fun social event. She’s only significant for the early parts of the book though, and after that, Sakamochi’s attitude is split into multiple authority figures.

It should be noted that in the film version of “Battle Royale,” Sakamochi’s character is substantially reworked; he is named Kitano, named for the legendary actor who plays him, Takeshi “Beat” Kitano. This character is very world weary, and while he takes some pleasure out of the Program, there is more depth and nuance to his actions than you’ll find in any adult character in Takami’s book or “The Hunger Games.”

In both stories, the killing game takes place in a Jungle setting (my mind’s eye imagined nearly identical spaces), and many similar scenarios take place because of this (specifically, the way characters will set traps/hide themselves/find water and food, etc). The only difference is that “Battle Royale” happens on an abandoned island, so occasionally, characters will find groups of empty houses.

At the start of both contests – the Hunger Games and the Battle Royale – the ‘players’ are each given a backpack with a random weapon and other supplies, such as food and water. This “evens” the playing field, to a degree, as the weapon could be invaluable (guns in “Battle Royale,” bows and arrows in “Hunger Games”) or entirely useless (one character gets a fork in “Battle Royale,” while Katniss gets nothing more than a knife in “Games”). In both stories, the protagonists don’t start doing well until they find better weapons (a bow for Katniss, guns for Shuya and co.).

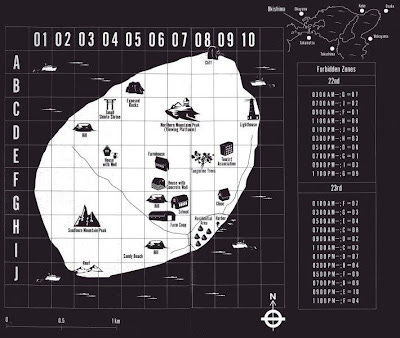

The map players are given in "Battle Royale"

In both stories, those in charge of the killing contest force the players closer together to ensure continued carnage. This is accomplished through the use of “forbidden zones” in “Battle Royale,” where players are told not to inhabit certain areas of the island at given times; otherwise, an electronic collar on their necks will explode and decapitate them. In “Hunger Games,” the ‘game-masters’ force players together by manipulating the environment. Early on, for instance, a giant wall of flame attacks Katniss, forcing her to flee to a different part of the arena. In both cases, the actions of those in charge limits the amount of space players have to battle, leading to greater conflict as the contest progresses.

In both novels, the ‘players’ are given periodic updates about who has died. In “Battle Royale,” this is accomplished by reading the names of the dead over a PA system, and in “The Hunger Games,” the faces of the dead are flashed in the sky. Even more obviously similar are how the characters react to these announcements: every address is invariably followed by Shuya and Katniss doing a mental rundown of who’s left, what this means for their chances, where survivors they’d like to meet up with might be, how the news affects where they should go or what they should do, etc. They also both have people they care for in the Games, so there’s lots of fretting when announcements start as the protagonists hope they don’t hear/see certain names/faces.

Both books feature an older and stronger figure assisting a younger, less experienced participant. In “The Hunger Games,” Katniss befriends and protects the youngest contestant, Rue, while in “Battle Royale,” Shuya and Noriko are assisted by Shogo Kawada, a slightly older boy who survived a previous Battle program. In this way, Shogo can also be seen as a parallel to Haymitch in “Hunger Games.” Haymitch is a previous ‘winner’ from Katniss’ home district, and assists her with both his knowledge and, later, supplies, something Shogo also does on a more direct level.

In both novels, the most powerful, capable participant is painted as the antagonist, and survives through to the very end: Kazuo Kiriyama in “Battle Royale” and Cato (no, not the Green Hornet’s sidekick) in “The Hunger Games.” Collins describes Cato (no, not Inspector Clouseau’s butler) and his actions very similarly to how Takami writes Kiriyama.

The surviving couples in both stories each become government targets; “Battle Royale” ends with Shuya and Noriko being chased by officers, while the government is very perturbed at Katniss and Peeta at the end of “Games.” As I understand it, the evil regime tries to kill them in subsequent books.

Of less import, but worth noting: the participants in “The Hunger Games” are aged between 12 and 18, the median of which is 15, the age of all participants in “Battle Royale.” Katniss Everdeen, protagonist of “Games,” is sixteen, suspiciously close in age to the characters in “Royale.”

"Oh my god...the similarities! They're so obvious!"

It seems to me that Suzanne Collins also borrowed liberally from Kinji Fukasaku’s 2000 film adaptation of “Battle Royale,” and I’d like to point out several such examples:

Similarities Between “Hunger Games” Book

and “Battle Royale” Movie

In “The Hunger Games,” Katniss has no dad and a deadbeat (or, at least, useless and disinterested) mother. Shuya Nanahara is an orphan in Takami’s book, but in the film, his father is also gone, and it’s implied that his mother was never there for him.

Though the Battle Royale program happens once a week in the novel, it is an annual event in Fukasaku’s film, just like the Hunger Games.

In “The Hunger Games,” each announcement of the dead is preceded by the Panem national anthem. While no music is played during the PA messages in Takami’s novel, the instructor Kitano plays pieces of classical music to start his announcements in Fukasaku’s film.

In fact, much of the pomp and circumstance surrounding the Hunger Games is similar to how Fukasaku imagines the Battle Royale. In Takami’s novel, the Program is always held in a secret location, and there is no media fanfare except to announce the name of the winner during nightly news bulletins. In the film, however, cameras come flooding in at the end of each annual Program to interview the winner, and Kitano runs the Program with darkly humorous fanfare. In addition to the aforementioned classical music, he shows the children an ironically cheerful instructional video before the Battle starts. Most importantly, Kitano very overtly views the Battle as sport, telling the students that “Life is a game.” This is a significant tonal departure from Takami’s novel, but it’s much closer to the Reality Show framework of “The Hunger Games.”

The humorous instructional video in "Battle Royale"

In the sequels to “The Hunger Games,” “Catching Fire” and “Mockingjay,” Peeta and Katniss, survivors of the Games, lead a revolution against the government that forced them to kill. Koushun Takami wrote no sequel to “Battle Royale,” but Kinji Fukasaku’s son Kenta did make a sequel to the film in 2004, titled “Battle Royale II: Requiem.” In it, Shuya and Noriko lead a revolution against the government that forced them to kill. This is one bit of ‘borrowing’ I will not hold against Collins, however, as I do not expect her to have sat through “Battle Royale II.” It is possibly one of the worst movies ever made, certainly among the most disappointing sequels.

Okay, now that I’ve established fairly overwhelming evidence for the derivative nature of “The Hunger Games,” let’s apply all this knowledge in more general terms. I’m sure some fans of “The Hunger Games” will look at all these similarities, shrug, and say “so what?” To that, I have to stress this point: context matters. Bullet point comparisons only tell part of the story. You actually have to sit down and read both novels to truly understand how derivative “The Hunger Games” feels. Again, I knew nothing about this book when I started reading it; “Battle Royale” was far from my mind. I hadn’t even perused it in years. But it only took a half hour of reading or so for me to feel like I’d experienced this story before.

Collins’ prose in the early chapters was a big indicator for me; it reads very similarly to the English translation of “Battle Royale.” Specifically, she’ll start in the present, following Katniss as she goes about her day, and presenting exposition through Katniss’ thoughts and reflections (the book is written in first person). It’s Katniss who tells us what the Hunger Games are, who Gale is, how her family history has played out, etc. Takami does the same thing through Shuya, albeit from a third-person perspective; Shuya tells us about “Battle Royale,” his thoughts give way to his personal history, backstories of his classmates, etc. The prose of the two novels differs significantly after a little while (Takami follows many characters omnisciently, while Collins focuses solely on Katniss), but it’s one of those tonal comparisons I just couldn’t ignore.

And when the Games actually start, it really is eerie how closely the contest mirrors the progression of Takami’s “Battle Royale.” Yes, “Hunger Games” has many original layers: the Reality Show angle, outside help from ‘sponsors,’ Katniss’ unfavorable opinion of the other contestants, etc. But underneath all that, the contests are unshakably similar. I tried to ignore this while reading, but I couldn’t: the rules, the logistics, the decisions characters make, etc….so much it felt so inescapably similar to a book that had made a big impact on me, and at a certain point, noticing similarities became a subconscious process. I understand the urge some readers have to put aside the comparisons in favor of Collins’ more creative elements, but this ignores the facts, and the facts are that much of “The Hunger Games” is way too close to “Battle Royale” for comfort.

But at the end of the day, they are separate works, with distinct goals and styles, and now it’s time to look at the differences. I believe the simplest way to describe the contrast is as follows:

“The Hunger Games” is the dumb American version of “Battle Royale.”

And I recognize that this statement is going to take some explaining if I am to avoid a ritual stoning. No matter. Even if “The Hunger Games” is your favorite book of all time, I’m confident you’ll see exactly what I mean soon enough…..

TO BE CONTINUED

Click to read part two...

This article is being presented in three parts on www.jonathanlack.com, with part 2 publishing tomorrow and part 3 on Thursday. If you would like to read the full, unedited version of the article, please e-mail webmaster@jonathanlack.com and we will send you a PDF version of the complete article.