Interview: Talking Time, Tech, and Fandom with Kanzenshuu, Anime's Greatest Fansite

Trading 'war stories' with the Dragon Ball fansite's founders, Mike LaBrie and Heath Cutler

October is exciting to me for two reasons: First, I’m defending my Ph.D. dissertation, titled Newtypes: Digital Technology and the Evolution of the Language of Anime, at the end of the month; Second, there’s a brand-new Dragon Ball series, Daima, premiering on October 11th. I wanted to celebrate these equally important life events by presenting this piece I wrote for my dissertation: A conversation with the founders of Kanzenshuu, the incredible Dragon Ball encyclopedia and forum that is the gold standard of English-language fansites. I spoke with Mike LaBrie (VegettoEX) and Heath Cutler (Hujio) in the summer of 2022 as research for a section of my dissertation that was eventually cut from the project; by the time that decision had been made, I had already produced this piece, so I still wanted to share it with the world, as our interviews produced a wealth of valuable insights. Now seemed like the perfect time. Many thanks to LaBrie and Cutler for their generosity. Enjoy!

When I think about the people, places, and works that influenced me as a scholar, I can name plenty of teachers and texts, but in truth, few have impacted me quite so profoundly, or for so long a time, as a Dragon Ball fansite started when web pages were static, ‘social media’ wasn’t yet an idea, and anime was sold three-episodes-a-pop on VHS – if you were lucky enough to find it officially distributed at all.

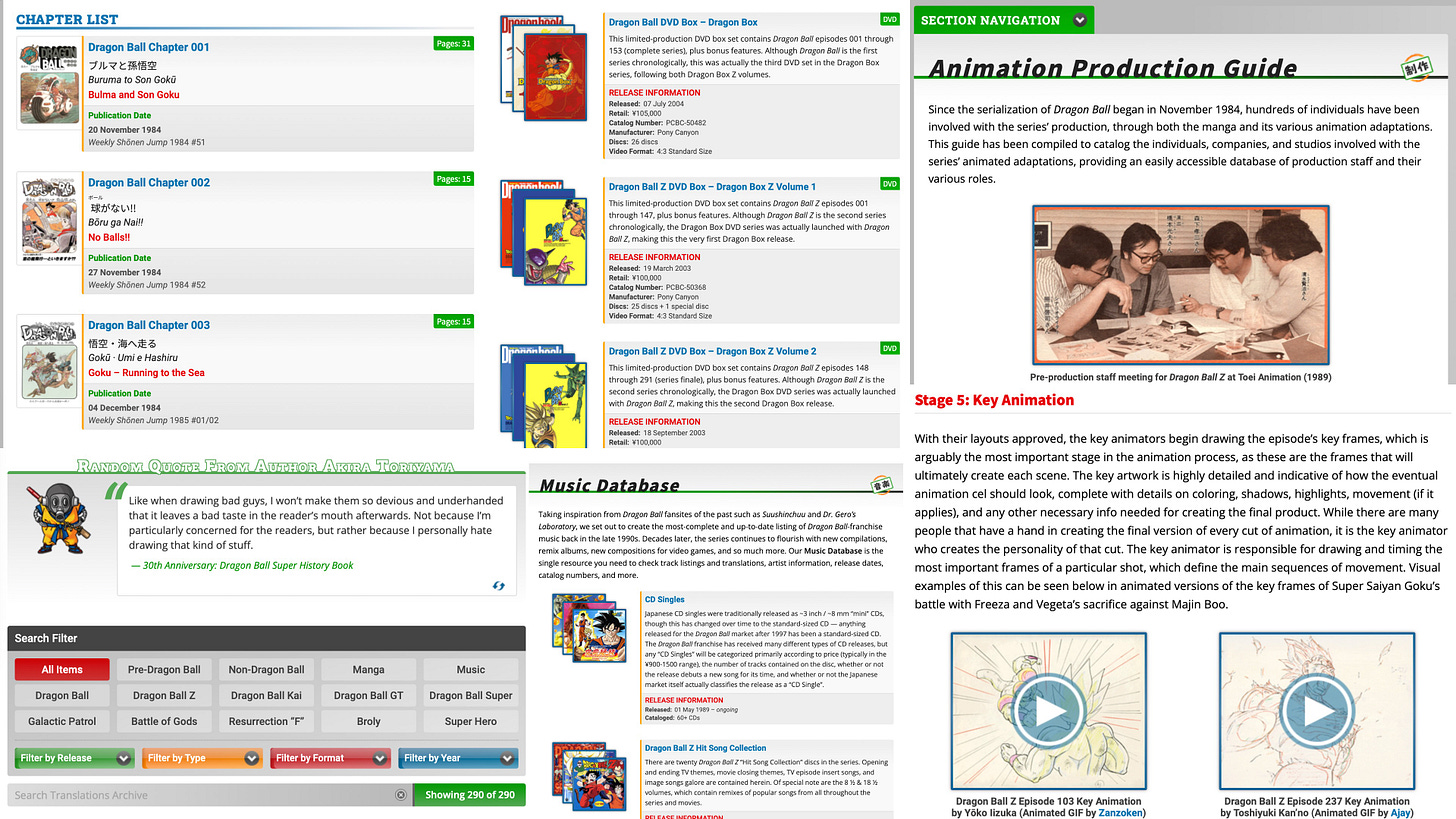

Kanzenshuu.com, which bills itself as “The Perfect Dragon Ball Collection,”1 is an astonishingly thorough, handsomely organized, and enduringly accessible English-language repository of just about everything one could ever hope to know about the globally popular anime franchise launched by Akira Toriyama’s classic manga. Among the many site’s many sections are ones detailing every episode across all the various television series with full episodic credits and summaries; listing each chapter of the manga with original issue and publication dates (information gleaned from sending ‘Senior Japan Correspondent’ Julian Grybowski “to prefectural libraries in Japan to pull out carts of magazines”2); hosting a massive library of translations from assorted guidebooks, author comments, interviews, and more; elaborate guides on everything from home video releases to music and soundtracks to one debunking rumors about the series that have spread across the internet; and even an in-depth, multi-part interactive “Animation Production Guide” that exhaustively details how the series was animated, defining all sorts of vocabulary and staff positions along the way; it is specifically about Dragon Ball, but is also one of the best and most accessible resources for explaining the cel animation process I have ever seen.

The site traces its origins back over 25 years ago, and has across the decades approached its mission to catalogue Dragon Ball information – and, just as importantly, combat misinformation – with what I can only describe as a profoundly academic rigor: a commitment to accuracy, organization, sourcing, and thoroughness that is rare on the internet (particularly where English-language anime fandom is concerned) and would more than pass muster in an academic setting.

“I know for me, it’s very inherent,” says Heath Cutler, known online as Hujio, one of the site’s co-founders.3 “I’ve always been a documentarian, I guess you would say. I like to do that. I find it fun … My father is a historian, so I grew up with that from a very young age, of respecting history, documenting it, and knowing what happened and how it should influence what can happen … And our hope is that other people will, in turn, see not only how well it has worked for us, but can hopefully replicate it. [Things are] so much easier to source when you can just say, ‘hey, it was from this magazine, this book, this interview that was given on TV that we happened across.’ And it’s not just pulled out of nowhere because we live in a world these days where information comes from all over the place. And frankly, a lot of people like to take advantage of that. And we have always been the counterculture to that, in our opinion.”

Fellow Kanzenshuu co-founder Mike LaBrie agrees. “Part of it is that’s who Heath and I and [the other founders] are as people.4 Heath and I have constantly talked about the stuff that we put on the site is generally because we didn’t know [the information], we wanted to figure it out, and we might as well make it into a section. If anyone else finds it useful, that’s great. But even just as basic as things like release dates for chapters, we would have these questions, and we’d be writing something or talking about something, and we didn’t know the answer. And we wanted to be correct about [it, so it became] the whole project. We got to go figure all this out ourselves.”

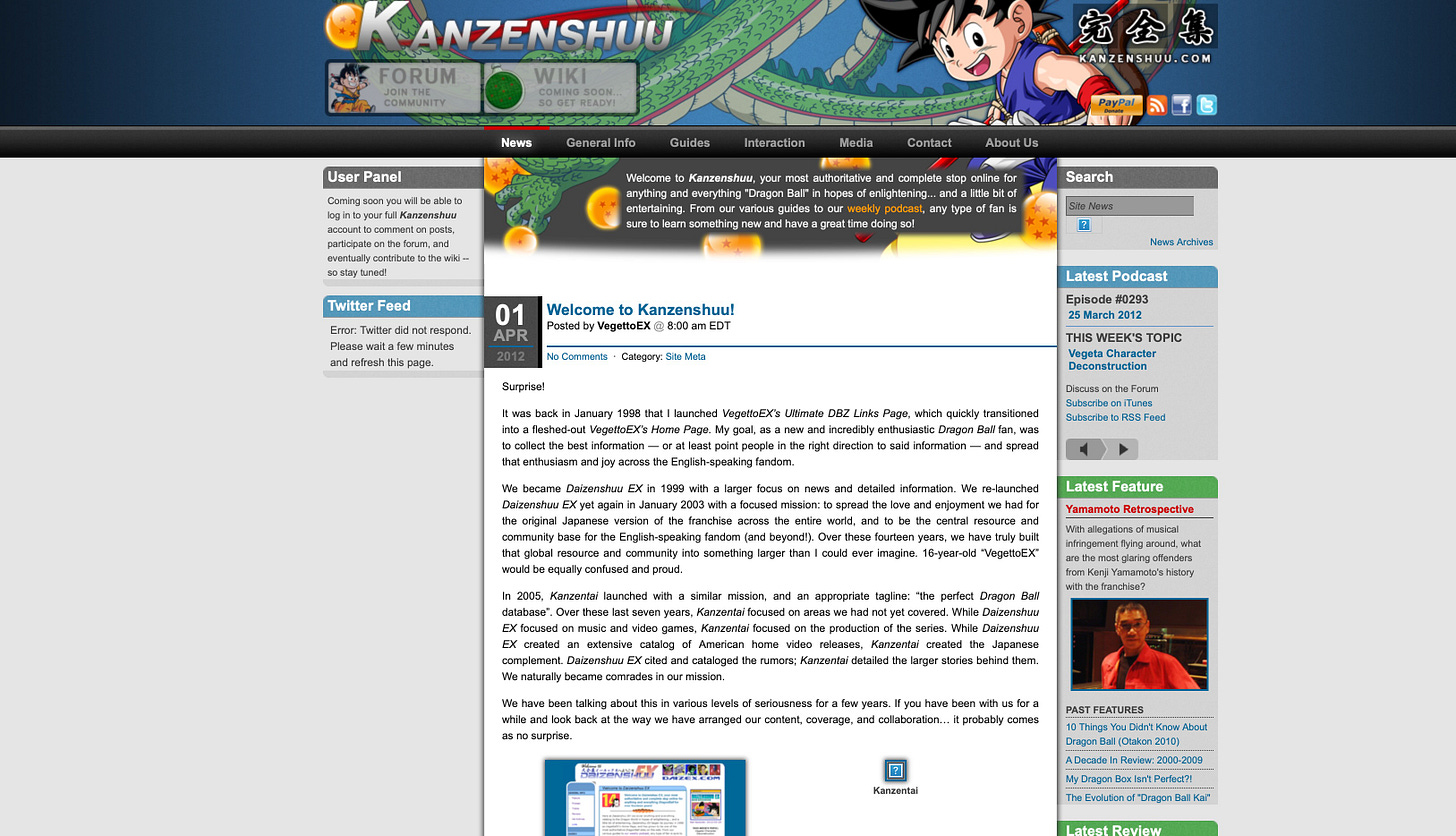

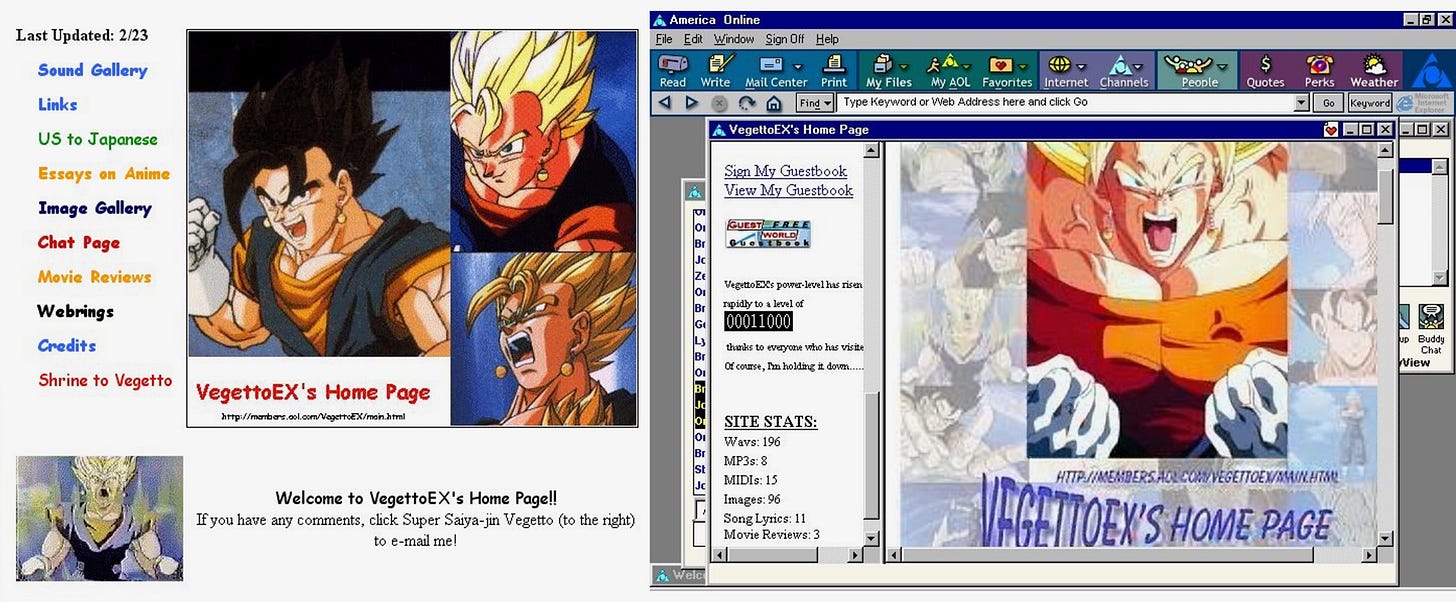

The site’s roots lie in an AOL page LaBrie created in 1998, when he was just 16, as part of what he considers the second generation of Dragon Ball fansites: those that emerged after Dragon Ball Z aired in North America for the first time in September 1996.5 First titled “VegettoEX’s Ultimate DBZ Links Page,” and then simply “VegettoEX’s Home Page” – VegettoEX was LaBrie’s online screenname6 – the site directed fellow fans to the best sources of Dragon Ball information on the internet. “[When] I think back to the sites that inspired me when I first got started,” LaBrie explains, “I always say Wuken’s Suushinchuu was my favorite and I think the most important.7 And when you go back to his news updates, he would cite specific Jump issues by name and by date, and that wasn’t something you saw on other sites. And that was the light bulb I didn’t know was going off in my head. It was like, ‘Oh, there are things out there that say things!’ … You’re talking about an actual magazine that has an actual release date with a real person who said a real quote in it … And that’s what got me going [back when] I first started visiting his site in like ‘96, ‘97, these were real things that someone could go out and buy and actually has this history in it. And I always kept that with me moving forward.”

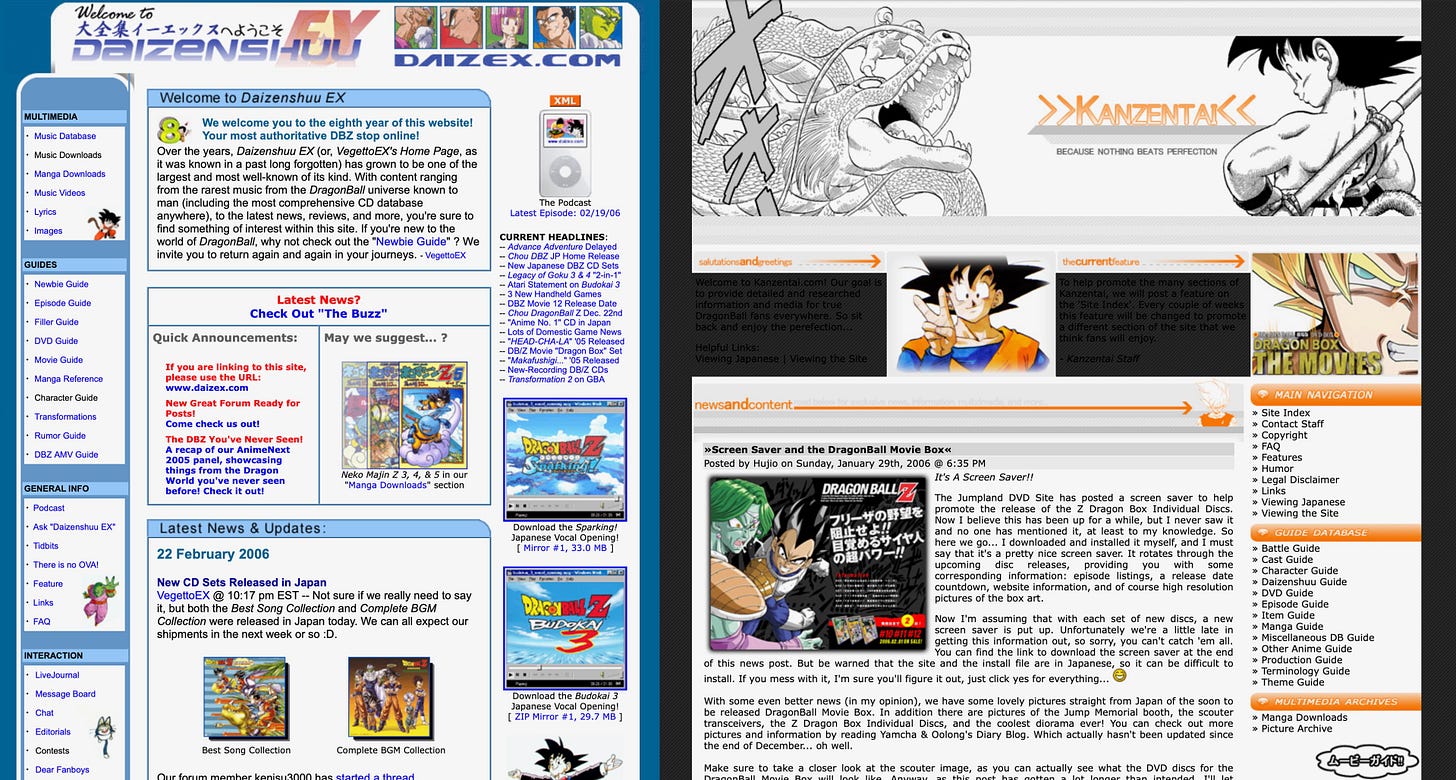

The page quickly grew in ambition, transitioning into a site cataloguing news and information of its own, rebranded as Daizenshuu EX on March 20th, 2000. After “a brief hiatus,” Daizenshuu EX had a major relaunch in January 2003, with LaBrie now working alongside Grybowski, who studied Japanese and could thus do translations (and eventually came to live and work in Japan).8 It was on this incarnation of the site that many of the guides and resources that populate Kanzenshuu today originated (along with an unusually well-moderated, polite, and informative set of Forums, where fans could discuss, debate, and exchange information). The other half of Kanzenshuu comes from a site Cutler founded in 2005, called Kanzentai, inspired by sites like Daizenshuu EX and his experiences on those forums, and as a merging of his hobbyist interest in anime and website development.

“Toei Animation had just started releasing the Dragon Boxes in Japan, which was the first time that any Dragon Ball series had been released on home video,”9 Cutler explains. “2005 also marked the first time that I had an actual full-time job with expendable income … At the same time, Shueisha had just started releasing the Kanzenban editions of the manga. So here I am with all this money and a love for two things. And I just wanted to share that. I was on the Daizenshuu EX forums at the time and [realized] through talking to people there, not everyone could afford these. These are very expensive items coming out of Japan … and I wanted to share what I had with other people, and that’s really where it started … We jumped in and created Kanzentai, where we started an extensive episode guide, where we provide all the episode credits, provide animation details, background stories for episodes ... we could share the wealth of information which was not available anywhere else.” Cutler and LaBrie became friends during this period, and eventually realized their two sites, which already complemented one another in the kinds of information they catalogued, could be better – and more efficient – as one, leading to their combination, and the creation of Kanzenshuu, in 2012.

‘Sharing information’ is the key idea behind Kanzenshuu, and one that came up over and over in my discussions with LaBrie and Cutler. “That’s really what it’s all about for us at this point,” Cutler explained. The site functions as a “repository of information that, frankly, most other people, the ‘lay fan,’ do not have access to, that we felt was crucial enough to document, maintain, and share with people. And everybody is free to use it. And we don’t charge anything for anything, at all, that we do. And really, that’s been our mantra.”

This is one of my favorite things about Kanzenshuu, and representative of what fandom can be at its very best. Fandom and academia aren’t so dissimilar, after all; they can both fall into ruts of elitism and ‘gatekeeping,’ can be exclusionary and uninviting when they take a more defensive or selective posture. But in their ideal form, fandom and academia share a desire to find and share knowledge for its own intrinsic ends, with a community that is allowed and invited to grow as information spreads.

“I think that is inherent to the culture,” Cutler replied when I asked him about this. “Especially with Japanese manga and anime fandom, because it’s such a staple. I mean, it’s a visual medium that everyone can enjoy, that speaks to everyone for the most part, depending on what type of series you like, what type of storytelling. And one of the main barriers is it’s in a different language. So from the get-go, there’s always been a sharing component, especially when there wasn’t access in the early days. [There were a lot of people like] Greg Werner, so many people from back in the day, that that would type up summaries after reading manga chapters because nobody else had access to that. And it was done for many, many series, not just Dragon Ball … the information sharing, I think, is key. It’s crucial to keeping people involved. And I think that’s the main way to keep fandom strong and growing and going is when you do have information sharing.”

At the same time, a theme that came out of my conversation was LaBrie was whether the challenges of those ‘early days’ of American anime fandom, when Japanese media wasn’t as easily accessible as it is now, was a major factor in creating that wide-ranging ‘thirst’ for knowledge that still drives Kanzenshuu. “When I came in, you couldn’t just watch the series,” LaBrie explains. “You couldn’t just read the series. It didn’t exist all as one complete product, even in its homeland … fans [today] don’t know how good they have it, that they can load up their HDTV computer monitor, play episode 1, and it will auto-play to the end of the series in order. You know, that was a dream to me when I was getting into the series … I think there is some truth to the fact that [not having it all available is] what made us a little bit more of a ‘general’ fan. Back then, we didn’t know what we didn’t know. So we had to just scrape by and dig for anything that we could get our hands on. And that’s why I found an appreciation for the Hit Song Collections,10 the video games, the [Japanese] books that I couldn’t read that I was purchasing. I couldn’t watch the next episode, so I had to go find something else related to the series.”

I found myself resonating a lot with what LaBrie was saying here; around the time I conducted this interview, Sean Chapman and I were launching our anime podcast, Japanimation Station, with a series of episodes on the 2003 anime Fullmetal Alchemist – which several of our listeners were surprised to hear I had, as a kid, collected one DVD at a time, each containing just four episodes, over a period of several years. And as a 50-episode show, Fullmetal Alchemist was a lot easier to collect than Dragon Ball, which in its original run from 1986 to 1997 aired 508.11 A fandom built around scarcity ignites the imagination in ways the easy access of the streaming era probably doesn’t; the thirst for knowledge is strongest when it cannot so easily be quenched.

Technology, of course, drives so much of this, partially determining not only what is accessible, but what kinds of fandom are encouraged. “You know, when I came in, it was very general,” LaBrie reflected. “I just wanted to learn everything I could about every aspect of [Dragon Ball], but it was a very cursory, broad understanding of everything. Now you have folks that can identify individual animators from the smoke that’s on the screen, and I can’t comprehend that.12 It’s crazy to me that they’re able to do that … And I think the technology [is what allows that]. You could freeze frame on VHS before, sure. But you’d have the tracking on the screen. It’d be a little wobbly. You’d be going over a [coaxial] connection.13 Now we have … 1080p signals [that are] digitally produced, you freeze a frame and that is the frame. I mean, that’s it. There’s nothing else to it … I think when you are truly in love with something, you find your own niche within that as well. And this democratization of technology, if you will, has allowed everyone to explore those interests to their heart’s content.”

All these changes in time, technology, and fandom have long made me curious if Kanzenshuu could be a repeatable phenomenon – if it could be done again, with a different series, on the platforms and under the paradigms of the contemporary internet. Could a contemporary international anime hit – say, Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – one day have its own Kanzenshuu? Cutler and LaBrie had slightly different takes on this.

“Could it be repeated? Absolutely,” LaBrie told me, emphatically. “Would someone want to do it? I don’t know. When I came in, the technology was very varied … You had to know all these different aspects of technology. And I think that’s what allowed Heath and I to make our websites the way we did, where we … were a jack of all trades, we knew a little bit about everything: to set up a website, to FTP files14 to a site, to edit the graphics to go on a site. You know, you come in now, people are so accustomed to ‘I run a Twitter account,’ ‘I run a YouTube page.’ And I certainly don’t begrudge … anyone who does those very hyper specific things. That’s a hustle I’ll never understand or never want to do. But it’s very different because you’re not paying for your web hosting. You’re not individually responsible for the upkeep on your software that runs your platform, and all of that stuff is handled for you, you know? So it’s a very different kind of thing.” Still, despite all the changes in time and technology, LaBrie ultimately landed back on his initial adamancy. “Could someone do it? Absolutely. They would just have to have that same kind of neurotic attachment to the underlying material.”

Cutler was less sure. “I think it would be extremely difficult,” he said, speaking first to the web design aspect of the project, which is his specialty at Kanzenshuu, and would probably be easier today given the wealth of consumer tools available. The challenge, as he sees it, lies in the content itself. “I do think it would be hard to create the number of pages and the amount, just a massive amount of content that there actually is sitting there that you don’t really realize. Wikis have become a huge thing. In fact, we have our own15 and I can’t even tell you – I think there have been four or five of us total working on the main website for all these years and combined our own materials to create what is there now … But we have probably about 50 people total that are working on our Wiki right now, and they’ve been doing that for almost five years ... and they haven’t even touched the number of pages that we have on the main website, and that’s a Wiki with way more people … So I think for, say, two to four people to sit down and try to do something equivalent to what we’ve done now, I’m not saying it’s not possible; I just think it would be difficult to compile everything and start from scratch.”

“The comment that I love receiving the most is ‘I wish there was a Kanzenshuu for ‘‘blank’’ – insert series here,” LaBrie reflected. “I feel good about that. And there probably are. The thing is, I don’t know what platform they’re using. There are only so many other things that I’m into at the level that I’m into Dragon Ball. Especially as I get older. I don’t need that minutia on things. So it’s tough. I do wonder if there is that kind of stuff out there. I’ve always wanted to start a consortium of old people who still run fan sites and, like, trade war stories. But I don’t know who they are or where they are.”

Another major factor in Kanzenshuu’s longevity – and perhaps most meaningful to me personally – is the podcast series LaBrie started in 2005 as Daizenshuu EX: The Podcast. It was one of the first uses of this new communication medium I was exposed to – as LaBrie notes, 2005 was the year podcast support was first built into Apple’s iTunes software – and from the beginning it was one of my favorites. Initially consisting of Mike and Julian talking about the series and the week’s news developments, the cast of contributors quickly grew, with different voices having unique areas of expertise, and topic segments dove deep into various aspects of the series, from music to home video releases to video games. I have particularly fond memories of the recurring “Manga Review of Awesomeness” segment, reviewing all 42 volumes of the original Dragon Ball manga, one book at a time, between 2007 and 2011 – perhaps not coincidentally, the exact years I was in high school, where I have distinct memories of sitting in the bleachers during gym class listening to it on my iPod.

To say this podcast was a massive influence on me would be an understatement. I started experimenting with podcasts in 2011, and launched the show I ultimately co-hosted for over a decade, The Weekly Stuff Podcast, in 2012. LaBrie’s series – renamed Kanzenshuu: The Podcast when Daizenshuu EX and Kanzentai merged in 2012 – has slowed in its pace of release over the years, but recently hit the milestone of 500 episodes.16 My podcast reached that number earlier this year; it was a full circle realization that, especially when I had the chance to talk to LaBrie face-to-face, I had to make part of our conversation.

“What’s new? What’s next?” LaBrie says of his thinking at the time, looking back on the creation of the podcast in 2005. “What’s something that I can do that would feel like a natural extension of what we were already doing and wouldn’t require this entire giant leap? … I always liked talking to people about things, and [podcasting] was new, and it was sonew that we could jump in at the ground floor on it. And that was exciting to me. Rather than trying to do something that was already running and rolling and had an established group of people, we could be first, honestly, to do it. That was exciting to me. And I just like talking to Julian about the series. So, you know, it just felt like ‘let’s try it out and see how it goes.’ And it went and continues to go, obviously not at the same pace, but we just loved doing it.”

Most interesting to me in LaBrie’s answer, though, was his reflection on how the podcast became, for him, a sort of hub in a growing network of friendships and connections. “…There always comes [a time], every decade or so, where I’m like,‘okay, I’ve met everyone I’m going to meet in Dragon Ball. I can make no more friends with this series,’” he explained. “And then something new will happen … [When] we started doing the podcast, different people started coming in. I would notice the work they were doing and I wanted to talk to them about it like, ‘Oh, I have a new friend for life through this.’ And so that’s always been exciting to me. … I’ve been involved with so many types of anime fandoms. I’ve been going to conventions since 1999 … I made anime music videos for about a decade in there, too. All of those things have allowed me to make these new lifetime friends, and I’ve funneled that appreciation back into the [podcast]. I’ve never really thought about it that way, but as I’m talking it through with you right now, I kind of realized that’s what I’ve been doing … I feel grateful for what they’ve given me, so I kind of want to keep it going and see where else that can lead me … I’ve always thought if I were to have a secret mutant power, it [would be] to bring the best of the best all together. I mean, I think I have something to contribute, but I really see myself as the ringleader of all the folks. And I want to bring the best people together.”

LaBrie also explained that, especially as time has gone on, worrying about the podcast’s ‘analytics’ – view counts, subscriber numbers, and so forth – have mattered less and less to him, to the point that he doesn’t bother looking at them anymore. “I have no idea if anyone even listens to the podcast anymore. Couldn’t tell you … For all I know, no one is listening to that show anymore, but I still do it … I’m just self-discovering that I’m pumping my gratitude back into the show. I enjoy talking to my friends about it. I know it’s going to be a chill, casual conversation, but I know I’m going to get something new out of it at the same time.” He explained to me that the podcast isn’t just a product he puts out, but a socialization exercise, a way to relax, something he enjoys doing regardless of who’s listening to the published episodes. It’s an attitude that matches the general Kanzenshuu philosophy of pursuing and sharing knowledge for its own intrinsic sake, rather than some firm material end – and it’s one that resonates with me a lot, because I would describe my love of podcasting in much the same way.

This led me to ask LaBrie, and later Cutler, a final question about an idea I had been chewing on for some time. Around the time my own show hit its tenth anniversary in 2022, my co-host Sean Chapman and I started reflecting more on why we do this and what we get out of it, and a theme that continually arose in our conversations was that our choice to never monetize our show or try making it our ‘job,’ a central source of income, probably did a lot to keep our enthusiasm alive. I ended my conversations with both Kanzenshuu founders by asking if keeping the site as a hobby – an extremely dedicated, long-running, prolific hobby, but a hobby nevertheless – was a factor in the site surviving with the longevity and integrity it has.

“That’s the only reason we’re still doing what we’re doing the way we do it,” LaBrie replied. “You know, if I had a quota of articles to write every day, I could do it. I got enough up in this noggin’ to beat the pants off of what Comic Book Resources17 is posting every day. But I’m not going to do it, because I will drive myself insane, and I will hate it by the time I’m done doing it.”

“In my opinion, I prefer it as a hobby,” Cutler explained. “We’ve always joked about, ‘Oh man, if we could get paid to do this.’ And I’m sure we could. But I would not have the same level of appreciation for what we do ... Because I view it as an outlet, I’m able to get away from other things that are happening in my life or work, in my career, and I can use this as my getaway. I think if it was a job, if we were producing income and this was my main source of income and we turned it into a corporation of some sort, I feel it would change in my mind because it wouldn’t be something that I want to go do, [but] something I have to go do … I don’t think we would be as creative with what we do. I think we would sometimes phone it in … And that’s not to take away from the people that do [do this as a full-time job], because I know they bust their butts and I know that many of them make great content. But I have also talked to many of them that say ‘my content has suffered because I do this.’ And I get that. I get both sides of it … There is that initial draw of [getting] paid to do something that I love. My problem is, eventually, is it still the thing you love? Because you’ve gotten paid for it? Because at some point I feel like there has to be a transition of ... treating this as a business as opposed to a passion. And it’s one thing that I don’t want to lose.”

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

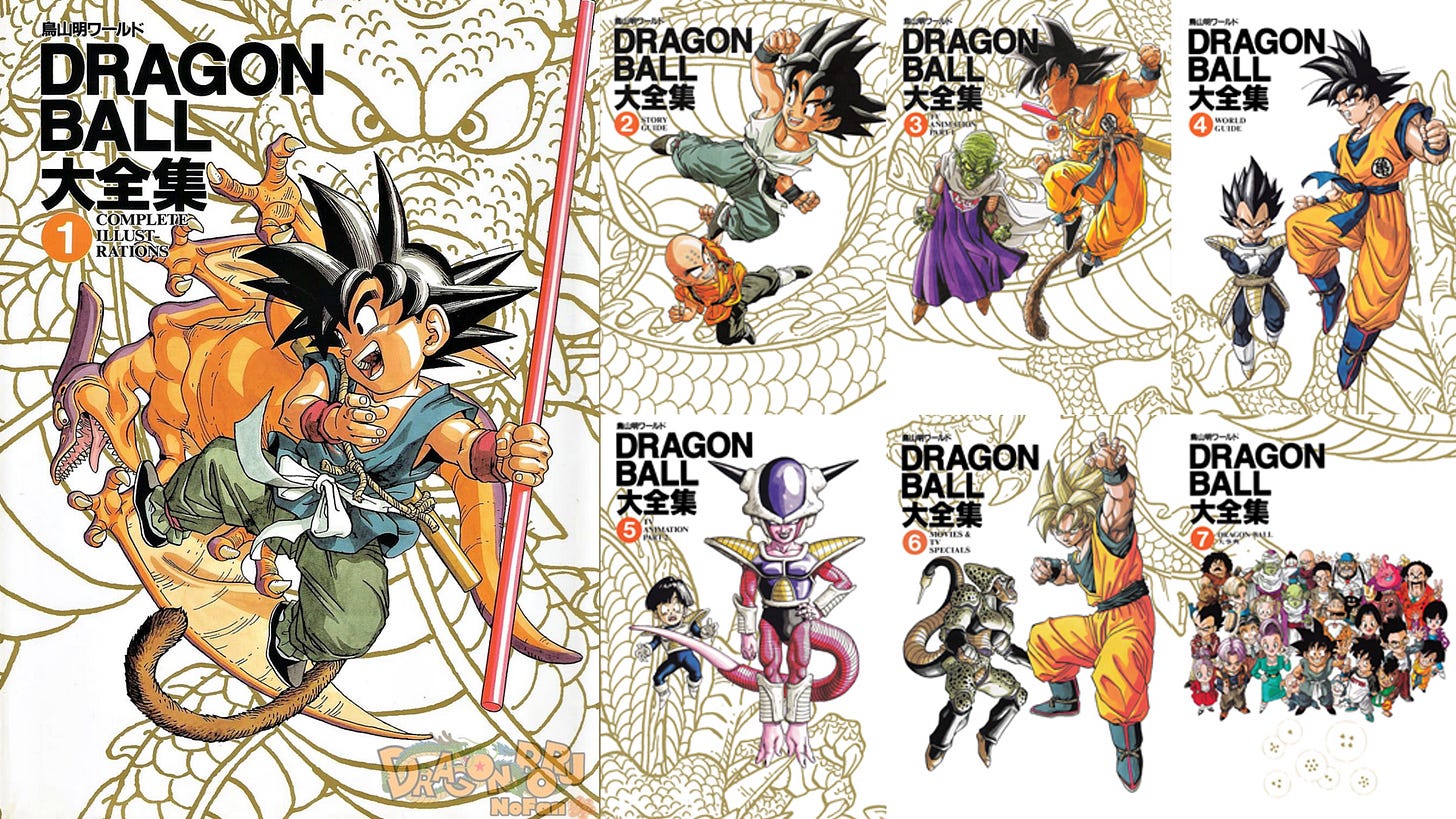

The name is an invented portmanteau combining the Japanese words kanzen / 完全 and zenshuu / 全集. Kanzen means ‘perfect’ or ‘complete,’ is prominently used in Dragon Ball to refer to the final form of the major villain Cell, and was the root word of one of Kanzenshuu’s two precursor sites, Kanzentai. Zenshuu means ‘complete works’ or ‘complete collection’, was used in a series of landmark guidebooks on the Dragon Ball franchise, the ‘Daizenshuu / 大全集’ (‘great complete collections,’ later republished as the Chōzenshū, or ‘super complete collections’), and was the root word of the other precursor site, Daizenshuu EX.

From an interview with Kanzenshuu co-founder Mike LaBrie conducted July 12th, 2022 over Zoom.

From an interview with Cutler conducted August 3rd, 2022 over Zoom.

Also including the aforementioned Julian Grybowski, aka SaiyaJedi, Translator and Senior Japan Correspondent for Daizenshuu and later Kanzenshuu, and Jake Schutz, aka “Herms”, former Translator and Head Researcher for Kanzentai and later Kanzenshuu.

An extensive investigation by Kanzenshuu revealed that the original air date for the English dub of Dragon Ball Z in North America was “‘during and around the weekend of September 14, 1996’” (the uncertainty stemming from the syndicated nature of the broadcast).

The name is a reference to the character Vegetto from Dragon Ball Z, the Potara fusion of Vegeta and Son Goku, the “to” coming from Goku’s Saiyan name, Kakarot, which in Japanese ends in -to.

This was “an influential English-language fansite back in the 90s,” in the words of Julian Grybowski in a 2013 Kanzenshuu forum post. The name Suushinchuu is a reference to the formal name of the 4-Star Dragon Ball in the series, 四星球, intentionally pronounced with the Chinese reading スーシンチュウ / sū shin chū.

According to later email correspondence with LaBrie in September 2024.

The Dragon Boxes are the most definitive home video release of the Dragon Ball, Dragon Ball Z, and Dragon Ball GT TV series, created from Toei’s film masters, with a much higher degree of visual fidelity than masters created and released elsewhere in the world; the Dragon Ball Z episodes were released in their Dragon Box form in the United States via FUNimation from 2009-2011 but fell out of print so quickly that a complete set can run around $2000 on the secondhand market. Some criticisms of these masters have arisen in recent years based on their color correction (or lack thereof), and much better audio masters than those Toei included have since been found and disseminated by the fandom; still, the Dragon Boxes remain the most ‘complete’ and faithful official releases of the entire series, and the default, best-available source material for subsequent fan-driven restorations.

Referring to a series of Dragon Ball albums collecting music from and inspired by the series, all now dutifully catalogued on Kanzenshuu’s music guide.

Totaling the episode counts for Dragon Ball (153), Dragon Ball Z (291), and Dragon Ball GT (64) which maintained the same weekly time slot for that entire 11-year period.

Amusingly, on the day I was writing this up, a video showed up on my YouTube recommended page of AnimeAjay breaking down the animation in the eighth Dragon Ball Z movie, 1993’s Burn Up!! A Red-Hot, Raging, Super-Fierce Fight, where he refers to “Shida Smoke” several times, referencing the distinctive smoke animation from animator Naotoshi Shida. This is exactly the kind of granular eye for detail LaBrie is discussing in this quote.

Coaxial connectors are a now-outdated connection technology for TV “consisting of two concentric conductors separated by an insulator,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Referring to the File Transfer Protocols used to move files from server to client over a network.

The Kanzenshuu Wiki was announced alongside the merging of the sites on April 1st, 2012, but is as of this writing still a work-in-progress. It is mostly closed to the public, with work proceeding behind the scenes by a small number of hand-picked contributors, in contrast to the usual conception of Wikis which allow editing by any registered user.

The 500th episode aired April 1st, 2023, several months after I conducted these interviews; April 1st is a meaningful date for Kanzenshuu, as it was the date the two sites merged in 2012 (leading some, at the time, to believe it was an April Fool’s joke).

A terrible website.