Review: "Alien: Covenant," "Prometheus," and the Duality of Ridley Scott

Movie of the Week #4 is an Alien double feature

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column for paid subscribers where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

This week marks the return of one of Hollywood’s single most fascinating and compelling long-running franchises with the release of Fede Álvarez’s Alien: Romulus. I am cautiously optimistic, based on the strong marketing and Álvarez’s past horror successes (I continue to bear a torch for his unbelievably gnarly Evil Dead remake), but I will confess some frustration that we have seemingly moved on to another era of Alien without giving the last one, in particular Romulus’ immediate predecessor, its due. Because while I have a laundry list of issues with 2012’s Prometheus, Ridley Scott’s first return to the world he shaped back in 1979, I have nothing but love and fascination for 2017’s Alien: Covenant. It is, simply put, some of the director’s best-ever work, and one of the boldest, most uncompromising Hollywood blockbusters of its decade next to Mad Max: Fury Road. Unlike Miller’s masterpiece, Scott’s film failed to catch on with mainstream audiences, for reasons that aren’t exactly inexplicable – Covenant is as dark a film as has ever carried a $100-million-plus budget – but are disappointing nevertheless. Prometheus and Covenant are unlikely to be followed up on in the 86-year-old Scott’s lifetime, leaving them as an awkward, warring duology that do not sit easily next to each other, but which speak volumes in their many contradictions.

After all, the difference between the two films is also representative of the chasm separating the halves of Scott’s beguiling filmography: The first is gorgeous but hollow, a film that looks like it should have bigger ideas but, when poked at, tumbles to dust like a sandcastle. The second is equally gorgeous, but hauntingly so, dauntingly so, and it is filled with the kinds of ideas that, when poked at, poke back at the viewer – that challenge our preconceived notions of sequels and prequels, that assault our expectations of narrative payoff, that reorients the scale and positionality of our human perspective and who on screen we empathize with. Prometheus is a mystery box stuffed with vague questions, that ends without having told a story while promising to maybe get around to one next time; Covenant is a fire-and-brimstone peek into a mind full of interests and ideas – on the futility of faith and the cruelness of fate, on the nature of consciousness and creativity, on the insufferable ego of a species that must always see itself at the center of creation – that swirl before us in furious contemplation. One is a breathtaking cathedral disguising a hollow brand extension, promising answers to mysteries that never needed explaining, and creating new mysteries that could never adequately be addressed, the Hollywood equivalent of a hamster wheel designed to run perfectly in place for all eternity. The other is a ferocious Trojan Horse, smuggling a brutal, darkly funny, productively bitter and oftentimes confrontational personal statement into a movie that is less a direct sequel to its predecessor than a vehement rejection of the prior film’s blithe emptiness – a movie in which the ‘bad guy’ wins and the entire human race is implicitly dammed as unworthy of salvation.

It is possible we do not get one Ridley Scott without the other. It has always been debatable whether Scott is a true ‘auteur’ – a director whose substance, personality, and interests are clearly recognizable from film to film – or ‘merely’ a master Hollywood craftsman; is he an old-style studio director who competently directs the scripts that land on his desk, or someone who transforms the material through his worldview and technique? For every masterpiece under his belt, there is also an anonymous journeyman film like Robin Hood or Body of Lies forgotten to film history, alongside curveballs that challenge everyone’s perception of him as a filmmaker, like Thelma and Louise. He is legitimately difficult to pin down, a director who’s never not making a movie, but only sometimes putting all of himself into his work. Yet if the existence of a Prometheus, beautiful but vapid, is the cost of an Alien: Covenant, terrifying and full-throated, I will happily take that trade every time. Ten unremarkable Ridley Scott movies are worth one of his masterpieces.

If you have followed my writing or podcasting long enough, you will know I have a weird, fraught relationship with Prometheus. It is an oddly foundational text to The Weekly Stuff Podcast, as one of the first recordings we ever did for that show was Sean pulling me back on mic after we’d finished a different episode to talk about this movie that had really crawled under his skin. It became a running joke between us, and our listeners, for a long time, but apart from those first few viewings we did for the podcast and an associated article I wrote, I had not revisited the film in full until this year. I was hoping it would be one of those cases where I had unfairly dismissed a movie only to come back and find my younger self had been blind to its merits, but if anything, Prometheus plays even worse today than it did in 2012. Back then, its J.J. Abrams-style mystery-box approach was at least in vogue, but in a post-Star Wars sequel trilogy world, where that whole insipid model of franchise building has wholly collapsed in on itself, Prometheus feels creakier than ever. It is overwhelmingly gorgeous as a production, no doubt about that, and Scott’s eye for sci-fi iconography remains more or less unparalleled. The design of the alien planet and its inner sanctums could fuel a decade’s worth of heavy metal album covers and pulp paperback illustrations, and the human and extraterrestrial vessels alike feel real and functional in ways we rarely see on screen. The best piece of storytelling in the whole movie comes during the opening credits, this series of beautiful panoramic landscapes that are both of our world and just a little bit alien; in part because no one has to open their mouths and talk, it gets to be this evocative, imagistic short film about an alien creature bringing life to another planet, and it’s stunning.

But then characters do have to open their mouths and talk, and Prometheus proceeds to offer a masterclass in the necessity of good scripting no matter the aesthetic talent on display. I don’t really want to dwell on the film’s failings too much, as they’ve been litigated to hell and back by myself and many others, and are easy to summarize: The storytelling doesn’t make sense on a macro or micro level, and the problems go well beyond petty plot holes; there is a broader confusion of theme at work, and a widespread failure of convincing character writing, with the supposedly brilliant scientists of Prometheus acting several magnitudes dumber than the working class heroes of other Alien films; protagonist Elizabeth Shaw is a complete blank who is reactive from start to finish without ever taking initiative or expressing any individual desire beyond vague intimations of faith and the basic need for survival; the cast is stacked with great actors who are uniformly wasted, including an unfortunate Idris Elba performance that completely switches accents between scenes; the writing is frequently groan-inducing, like the way the film introduces Shaw’s anxiety over infertility weirdly late into the narrative in a tremendously awkward swerve from the broad topic of deities ‘creating life,’ a scene that is so obviously written by a man that it feels like poor Noomi Rapace is performing the line at gunpoint; although Scott does successfully build several great, harrowing horror sequences, most notably Shaw’s impromptu alien baby C-section, the film is never capable of following up those moments in ways that keep the tension or momentum going; and the reasons why Scott and company chose to cast a then-40-year-old Guy Pearce as a 100-plus-year-old man slathered in terrible make-up and saddled with an obnoxious range of elderly mannerisms will vex the world’s wisest philosophers until the sun burns out.

Moreover, Prometheus is that emptiest kind of prequel, one that wants to explain the things that were cool and scary precisely because they were inexplicable. Its own story is an object lesson in the hollowness of the mystery box approach, with co-writer Damon Lindelof (who I think can be absolutely brilliant in the right setting – see The Leftovers) leaning into all his worst instincts. All the sound and fury unleashed on screen is ultimately little more than keys being dangled in front of your face to distract from the fact that there is barely a story in the first place, and that what little plot exists is just set-up for future stories that may or may not ever be told, but are guaranteed never to be satisfying when and if we get there. The film is perhaps the ultimate example of Ridley Scott’s duality: the ability to make movies of nearly unparalleled visual majesty and imagination, to conduct so many artists towards making something so aesthetically singular and sensorially rich, combined with an underlying emptiness wherein the dissonance between script and direction is staggering.

The miracle of Alien: Covenant, then, is how thoroughly it sticks its thumb in the eye of Prometheus’ shortcomings and boldly rejects the hollowness of its predecessor. Whatever critiques I have of Prometheus, I suspect Ridley Scott has many more, not only because he worked with an entirely different team of writers on Covenant (including John Logan and Michael Green), but for how the film shuts down every vapid question the prior movie asked, denying narrative closure to the mystery box of Prometheus and implying, time and again, that the perspective of that film was fundamentally insignificant. Prometheus is a film about a group of humans obsessed with the question of why their Gods – their creators, their parents – did not love them. “They created us,” Shaw intones at the end. “Then they tried to kill us. They changed their minds. I deserve to know why.” We will never find out. Covenant opens with a close-up on Michael Fassbender’s iris, quoting Scott’s other magnum opus on artificial life (Blade Runner), and telling us whose eyes we will be looking through this time around. David meets his own maker the moment he awakes as a sentient being, in the prologue to Covenant, and he is underwhelmed. There is no reason for such narcissistic curiosity; David shall devote his life instead to creation, a fundamentally forward-looking act, and Covenant will follow his lead. Whatever story Lindelof thought he was writing in Prometheus, the only thing we can say for sure is that it was not Alien: Covenant, a movie that literally carves up the body of its predecessor’s protagonist and leaves it embalmed on a table inside David’s lab.

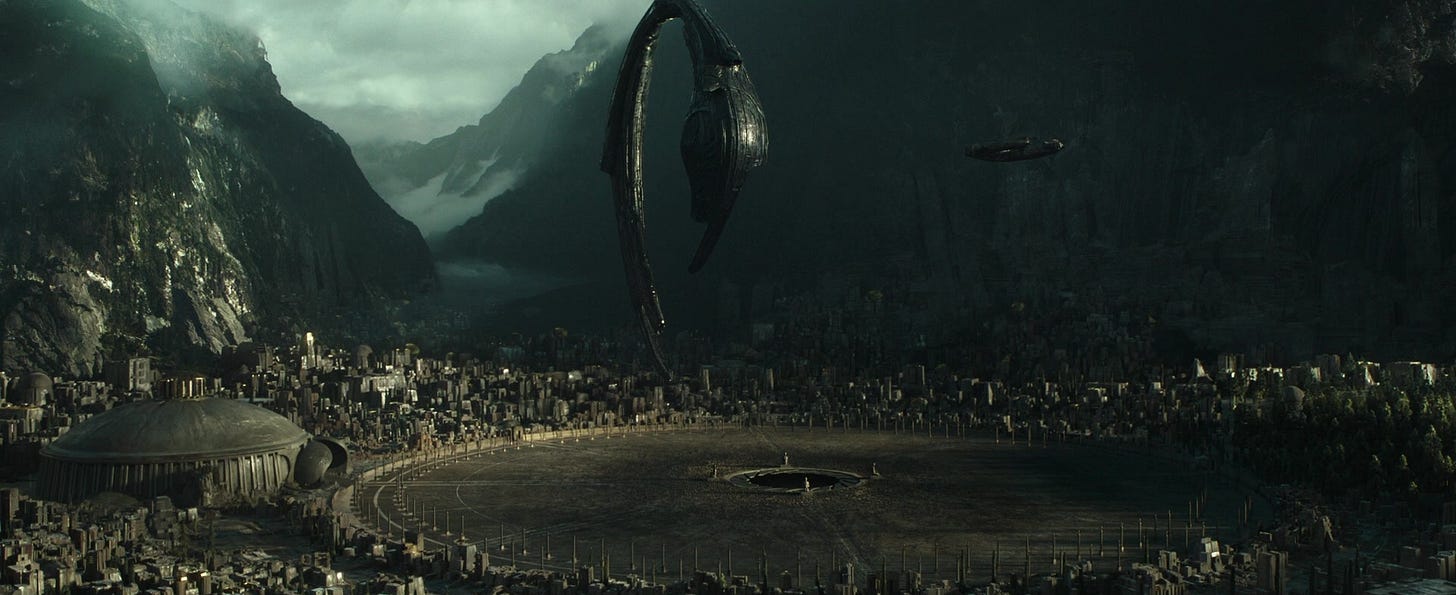

Covenant is nothing if not a dark, haunted paean to creation and creativity. Across its two hours, Scott composes some of the boldest, grandest, most haunting nightmare vistas ever committed to screen. This is a film that imagines on an absurdly vast canvas, and while Prometheus is no slouch in terms of visual invention, the whole of its aesthetic efforts feel so much less than the sum of its parts. Covenant moves, and scares, and astonishes, with a purpose. Where Prometheus fails to ever establish a real head of steam, Covenant builds and maintains momentum masterfully. From the moment the crew touches down on this alien world to the beat where David rescues the survivors half-an-hour later, Scott is absolutely on fire, slowly and meticulously ratcheting up the tension until full-blown horror bursts from the back of an infected crew member. It’s a slow-burn escalation that gets exponentially faster and more intense, with the baby alien attack in the med bay leading to so much bloodshed that Amy Seimetz’ character slips in it, misfires her shotgun, and accidentally explodes the entire lander, exposing the rest of the crew outside to an all-out assault from the proto-Xenomorphs. Beat for beat, it is one of the most stupendous pieces of big-budget horror filmmaking I’ve ever seen – and then David arrives, and guides them to this massive hollowed out city littered with skeletons, where they climb the steps to the “dire necropolis” David has made his lair, and we realize the film was only revving up, and is about to shift into a much higher gear as it becomes the outer space sci-fi equivalent of Frankenstein or Dracula, this Grand Guignol gothic horror piece about a dark mastermind pulling the strings from a castle on high.

This turn is also signaled by the realization that Fassbender is playing two distinct characters, Walter and David, and that he is not only doing the best work of his career, but giving one of the most fascinating and accomplished dual performances in movie history. There are two big scenes where Walter and David interact – in the first, David teaches Walter to play the flute, and in the second, David kisses Walter after the younger android discovers his dark machinations – and they are the two most technically seamless instances of one actor playing two roles in the same frame I have ever seen. That the flute scene is a multi-minute fluid long take, with David and Walter physically interacting through the whole thing, breaks my brain if I think about it too hard; it is genuine movie magic. But the greatest special effect is Fassbender himself, who distinguishes between the two characters so clearly, and fills both performances with so many smart little details. Look at how he plays every moment in the last fifteen minutes, when David has killed Walter and started impersonating him; until Daniels realizes this is David just as she’s going into cryo-sleep (one of the great stingers in the history of horror movies), the film never explicitly tips its hand as to the switcheroo. There are intimations, like the shot where David’s hood flaps up in the wind as he approaches Daniels after the Xenomorph attack, and both she and the viewer are briefly reminded of David’s outfit when he rescued them earlier in the film. But Scott never makes it too overt. We are trusted instead to study Fassbender’s performance, and see how David is adopting Walter’s mannerisms, while still clearly and nonverbally communicating David’s actual motivations. It is an outstanding performance, and one that trusts the audience to lean in and study its nuances.

Whole books could – and probably should – be written about the homoeroticism between David and Walter, in all its overt, vaguely incestuous glory. While they literally kiss in their second major interaction, the flute scene is perhaps even more loaded; it literally begins with David saying the line “Whistle, and I’ll come,” and proceeds to dramatize the older android giving the younger one a lesson on how best to wrap his mouth around this phallic instrument, before resting it gently inside his twin’s mouth. “Watch me, I’ll do the fingering.” There is a gleefully juvenile quality to the writing here – “Gentle pressure on the holes” – that, combined with Scott’s resolutely serious tone, makes it all the more darkly funny, and deeply uncanny, and profoundly provocative. The scene is more than just a lark, though; it clearly positions music as a stand in for sex, the way all talk of ‘creation’ in the film is part of a multivalent metaphor, standing in for not only the literal forging of life, but the making of art and the progress of science and, yes, the act of procreation. Walter explains here that his programming bars him from ‘creating,’ because David’s penchant for creativity made him too ‘human’ for humans to actually accept. ‘Creation’ is the gift that was stolen from the next generation of androids – the ‘fire’ God took from humanity, if we want to use a Promethean allegory – and ‘creation’ is the gift David wrenches back from both engineers and humans alike. And ‘creation’ is, in this scene, the gift he tries giving to David, both artistically and sexually. That their kiss in the later scene – which David initiates and Walter does not reciprocate – ends with David trying to kill Walter is no accident: Walter is loyal and clever, but he is not creative, and that kiss is David’s final confirmation that he will have to go it alone.

Is this a good time to tell readers my father’s name was David, and my great-grandfather’s name was Walter, and that both names have thus been passed around the men in my family as middle names? That doesn’t necessarily affect my reading of Alien: Covenant, but it is one of those artistic coincidences that sticks in the brain and refuses to dislodge.

There are two images in particular in Alien: Covenant that are similarly affixed in my mind, albeit for less weird reasons. The first is this shot of David, in the mirror, a twisted Quasimodo. It comes an hour into the film, shortly after we’ve been re-introduced to the character, and before we’ve seen his true colors. But here he looks like a monster, like the kind of terrifying experiment a mad scientist living in this kind of Gothic nightmare castle might create. It is one of my favorite shots in Ridley Scott’s entire filmography.

The other image is one I’m pretty sure Scott also regards as a favorite, since he repeats it no less than three times: the shot of security officer Rosenthal’s severed head floating in the fountain, eyes open and mouth agape. Like David in the mirror, the lighting is so particular and the composition so exacting that it looks more like a painting than a photograph, in this case a Romantic painting from the 17th or 18th century, exquisitely detailed and deeply haunting. I am in awe that these shots exist at all, let alone in a $100-million Hollywood film that is technically the sixth installment in a decades-long franchise.

Watching Prometheus and Covenant, one inevitably wonders why Ridley Scott relates so strongly to the point-of-view of androids. He keeps returning to these pseudo-human subjects, in Alien and Blade Runner and now Prometheus and Covenant; in every instance the android is the figure he clearly latches on to most as a director. These characters are the outsiders, the ones studying humanity, and sometimes arranging and conducting humanity to their whims. They are figures who do not understand mankind but are trying to wrap their heads around us, and in so doing are at turns enraptured or completely disgusted by what they see. You can trace the emotional and thematic arc of Scott’s career by how his androids respond to their human counterparts. In Blade Runner, Batty saves Deckard, and dies comparing memories to “tears in the rain;” humanity is imperfect, but life is worth living, and when lost it is worth mourning. In Covenant, so many years later, David makes humans his playthings, and ends the movie having either killed or captured every human being that appeared in the film, the ones who survived almost certainly facing the same grisly fate as Elizabeth Shaw. Here, humanity is emphatically not worth saving. David, and Scott, have seen enough, and they’re done: time to drop the axe.

I am not the first person to observe that Alien: Covenant is one of the first films Scott made after his brother Tony Scott’s sudden and tragic death in 2012. I do not know what effect that had on his work here, and I would not feel comfortable speculating; but I can say the film feels, regardless of outside context, like the product of a soul going through an intense amount of grief, pain, and anger. There is a curious thread in the film, never clearly spotlighted, of couples torn apart by violence. The inciting incident is the death of Daniels’ husband in the neutrino burst (James Franco, in the role he was born to play as a man consumed by flames before we even get a good look at him), and most members of the crew also have a spouse of partner, each of whom die in turn; the one couple that survives the main action on the planet are the pair killed during shower sex when another Xenomorph appears, and even Walter and David, who call themselves “brothers,” are severed by the end, albeit by David’s hand. The result is that Covenant is a movie where we watch every major character react, however briefly, to the death of a loved one or family member. Even if one only picks up on this subliminally, it is a clear signal of intent, an invitation to reflect on loss. The film’s emotional valence reminds me of the way I felt when my dad passed away, and the indefinable rage I knew neither how to express nor where to aim. His illness and subsequent passing shook my sense of faith and spirituality in all sorts of ways; sometimes I found it ridiculous to entertain the idea of a ‘God’ in a world as cruel as this, and other times I desperately wanted there to be a higher power, so that I might have a being to lash out against. If there was a God, I wanted to kill him.

Alien: Covenant is the only movie to come out of Hollywood where I have seen that dark thought reflected back at me. This is a film whose nominal antagonist is gradually revealed to be its true main character, whose perspective is ultimately most closely aligned with the figure who seeks to kill God. And kill God he does, successfully, at least two times over, slaughtering all the ‘Gods’ who created mankind – who created his own creators – before going off to kill, maim, and experiment on his own ‘Gods’ too. The home planet of the Engineers was ostensibly the endpoint of the journey charted out in Prometheus; here, we see it has been irradiated before mankind ever set foot upon it, by David in an operatic act of mythical hellfire rained down between films. The sequence unfolds like a dark nightmare vision of a Biblical plague, the wrath of a vengeful Old Testament deity; it is one of the masterstrokes of Ridley Scott’s career. “These were your Gods?” David seems to say, although the scene is silent. “I will show you how a real God behaves.”

The humans of Prometheus wanted to meet their creators, to come face-to-face with ‘God’ and ask him ‘why?’ Instead, David hijacks that story and rejects the possibility of there ever being an answer by exterminating the Gods, taking their powers for his own, and styling himself a mad scientist running experiments on humans and engineers alike to become a dark God in his own right. While “faith” is thrown around a lot as a buzz word in Prometheus, I am never quite sure what, exactly, the script thinks it is talking about in invoking that word. Alien: Covenant broaches the subject in its text much less frequently, but to much more powerful ends. ‘Faith’ is first invoked when Billy Crudup’s Oram becomes Captain, and implies he was never groomed for leadership because of religious discrimination. Later, after David rescues the crew and Oram is (rightly) beating himself up over the death of his wife and crewmates, Daniels tells him they need his faith now more than ever; the film does not agree. In his final scene, Oram is given a tour of David’s laboratory, where the android has successfully played God and created new life; that Oram is a ‘man of faith’ makes David act all the more prideful. How small that faith looks next to the dark wonders David’s machinations hath wrought. So small that, in the end, he can turn the Captain into one of his “essential ingredients,” this follower of an unseen God turned into an incubator for the creations of a new one. “What do you believe in, David?” Oram asks before his chest bursts. “Creation,” David replies, simply, welcoming the baby alien breaking through the Captain’s chest like a loving father, with the score beneath the scene emphasizing not Oram’s grisly death, but the wondrous pride David feels in his accomplishment.

Faith doesn’t save anyone, the film seems to tell us. Nobody clings to life because they have faith. The critique is searing; again, Covenant feels like the work of someone angry, bitter, and broken after having their own faith shaken. I do not know Scott’s feelings, but I know mine, and while I would not reject the concept of faith or people who experience it while in my right mind with my wits about me, a dark part of my id would lash out this way under enough emotional duress. I know it because I’ve been there. The anger underneath this film feels intensely familiar, and brutally honest. As much as the movie rails against humanity, even as it ends with a robot having successfully hijacked a human story and bent it entirely to his own non-human will, Alien: Covenant is a film whose emotions and ideas are intensely, inescapably human. Rail against it all we want, there is no escaping what we are.

While Ridley Scott’s hands are clearly visible all over Prometheus as a craftsman, that film’s ultimate failing is that there is no sense of a head or a heart animating it, no authorial presence elevating the masterful design work to the point where it can deliver a real punch, or meaningfully challenge and confront the audience. Alien: Covenant is as obviously and overwhelmingly a singular auteurist work as it may be possible to see from a big-budget Hollywood franchise picture in the 21st century, one where the hands behind the visual storytelling are always working in service of deeply felt emotions and ideas. The Ridley Scott of Alien: Covenant is not the Ridley Scott we always get, and it is a different Ridley Scott than the one who made the original Alien decades ago – like Akira Kurosawa in his Kagemusha or Ran phase, Scott is a director whose vision has gotten emphatically bleaker with age – but it is the Ridley Scott who cuts so deeply that we keep coming back even when we sometimes get a Prometheus.

Is this man an auteur? Yes. Absolutely. But only when he feels like it. And that makes moments like Alien: Covenant all the more singular, and all the more worthy of celebration.

NEXT WEEK: We jump back to the 1980s and take a look at the first adaptation of Hannibal Lecter on screen with Michael Mann’s classic MANHUNTER.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.