Review: "Eyes Wide Shut" and the dying dream of 20th-century cinema

Movie of the Week #19 examines a controversial classic at 25

Welcome to Movie of the Week, a Wednesday column where we take a look back at a classic, obscure, or otherwise interesting movie each and every week for paid subscribers. Follow this link for more details on everything you get subscribing to Fade to Lack!

The 159 minutes of Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut slowly cover a very simple character arc in gloriously deliberate detail: A deeply repressed bourgeois man is forced to confront that he is, in fact, human, and that he therefore has human urges and emotions. Within its languid, dream-like pace, the film finds such profundity in this idea. Perhaps there is even something metatextual here; for a director who was so often (if perhaps unfairly) accused of being cold, his films sometimes described as seeming like an alien examining humanity, Eyes Wide Shut is a moment when Kubrick connects with the messiness of humanity very intensely.

The bedroom argument near the beginning between Tom Cruise’s Bill and Nicole Kidman’s Alice, which takes up most of the second reel, is the key here. It is not a complex fight, nor one where either party has necessarily done anything wrong. But where Alice is honest and insightful enough to recognize that she has urges, and her husband has urges, and that being honest with each other about them can make their marriage healthier, his complete and utter denial of that which makes him human is off-putting to her – and eventually offensive, when his ingrained sexism starts shining through (his pigeon-holing of women as lacking sexual urges is part of the bourgeois pathology). He wants to pretend he lacks these urges, or at least has them under control, and wants her to pretend the same, and for them to go on pretending that their lives are happy and perfect, because this is, of course, what the social structure around them demands. Bill is deeply and profoundly repressed, refusing to confront his own instincts or emotions, and that sets Alice off. Because she knows, from experience, that it is when she acknowledges her own urges – analyzes them, thinks about them, lets them flood her conscience – that she starts to understand them, and suddenly has an awareness of what is most important in life. Kubrick’s film is in no way anti-marriage, or even particularly cynical about the idea of marriage; it simply posits that a healthy marriage is one in which the participants don’t pretend that a vow erases every other instinct – that one can be committed to someone and still fantasize or feel attraction to others, and that if they can do that and still feel loyal to their partner at the end of the day, the union remains strong.

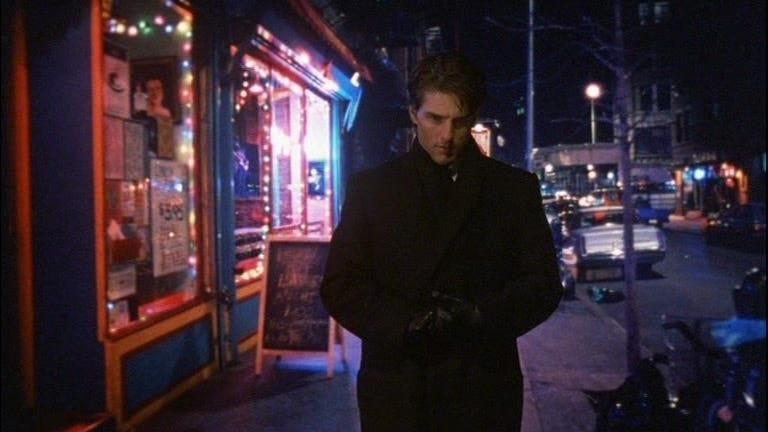

Thus, Bill’s arc is about confronting his own repression, and it is a glacial shift. Tom Cruise is used so perfectly here, with such immense self-awareness, Kubrick ruthlessly employing his slightly off-kilter movie star persona, in a setting that is simultaneously realistic and surreal, to make him a sort of heightened poster boy for bourgeois sexual repression. I cannot help but wonder how much Cruise was in on the joke; the performance is both entirely straight-faced and extremely, painfully funny, a reminder that while Kubrick only ever made one outright comedy (Dr. Strangelove), there is a sly, quiet humor to his work that can be absolutely gut-busting if you’re on the right wavelength. In this way, Eyes Wide Shut is something of a companion piece to Barry Lyndon, another film that uses an actor with movie-star good looks very much against the grain.

In any case, Cruise is fantastic here, and what is most funny and compelling to me about the character and his work is to see Bill come into contact with all these very human moments. He meets a grieving woman who has a huge burst of real, raw emotion in front of him, and he has no idea what to do with it; he tries hiring a sex worker, and has no idea how to act naturally around her (“what do you recommend?”); the way he keeps pulling out his ID every few minutes, often without reason, because he wants to pound his own chest. You can practically feel the stick up his ass. In each instance, Bill encounters vulnerability, and in return he can only act – be an actor, be actorly, be mannered and heightened in spite, or because of, his attempts to blend in –because that is what repression does to a person. It forces one to assume a face, a mask, a posture.

Speaking of masks: the ritualistic orgy, the film’s iconic centerpiece, shakes Bill so deeply because it is, in effect, a mirror – a ritual, in which the bourgeois come together to unleash their sexual urges, but do so under cloaks and masks, in a pre-ordained, ceremonial fashion, in a hidden location, with strict security everywhere. They allow themselves to be consumed by their human urges, but only if those acts are ordered within a strict social structure. It is social, emotional, and sexual repression personified: the absolute, abject separation between identity and urge, each person there decoupling themselves from their face and identity to ‘let loose,’ but only in the most highly ordered of ways. This is either the ultimate zenith point of what Bill could become, or the ultimate object of his fear.

These are people living with ‘eyes wide shut’ – willfully living in a state of repression, ‘widely’ closing their eyes to the reality of their own bodies. And that’s who Bill is at the beginning of the film, too. By the end, his eyes have truly been opened, and he has had a genuine emotional awakening. As it ends, the film is very clear about its message: the characters are now awake, but the question is whether or not they can keep their eyes open. Setting the final scene in an ostentatious toy store is important; Bill and Alice are back among the bourgeois, back in their upper-class milieu, but now that their eyes are open – now that they have had a serious, adult conversation about their own urges and wants and emotions – maybe there is a way to live in this world without repressing every feeling along the way. As long as the film is, the characters have really only moved and grown a tiny little bit, but the first step they’ve taken, to awaken as human beings, is crucial. Maybe there is a hope for marriage, if partners can look each other in the eye and share their honest feelings – if they can, as Alice says, “fuck.”

Lest it go unsaid amidst the analysis, Eyes Wide Shut is also a tremendously entertaining film. Given its pace and length, the film could feel like a chore, but no part of it does. The cinematography is gorgeous and immersive, the production design striking and haunting, all of it just a few degrees off from reality, a dream space where the dreamer is unaware they are asleep. Every scene sizzles, each individual sequence a rich, layered, consistently surprising masterclass, with side-characters shuffling in and out in a parade of wonderful performances, from actors and known and unknown. As long as the film is, it feels timeless, in the sense that time is irrelevant while watching, the hands of the clock ceasing to turn, or to matter; and the longest scenes, the ones Kubrick allows the most room to breathe, are the most involving. From the opening argument to the ritual orgy to the pool table chat between Cruise and Sydney Pollack, Kubrick lets these scenes play to full, uninterrupted length, in an almost theatrical fashion, and the more they go, the richer they get (a fact true of each unbroken individual shot, too). As noted before, the film also functions as a terrific dark comedy, and it has a wonderfully playful sense of style at times (such as the rapid zoom-in on the mysterious woman who helped Bill during the ‘expulsion’ sequence at the orgy). The film is self-aware about what it is, and is legitimately fun and entertaining even as it is deeply thought-provoking and intellectually rewarding. Eyes Wide Shut is, like each of Kubrick’s masterworks, a complete package, a world unto itself, one that reveals more the further one wades into its waters.

It’s been 25 years now since Kubrick died, the film released just four months later, but even as its two stars continue to be alive and relevant, Eyes Wide Shut feels like it’s from an entirely different era, one more removed from us than the quarter-century anniversary would suggest. This was a Warner Bros. production and release, made with a sizable budget, marketed around its director as much as its stars; it’s not that this sort of thing never happens anymore – Spielberg, Scorsese, and, now, Christopher Nolan get this kind of treatment still, though nobody except, perhaps, Tom Cruise himself still carries that kind of star power as an actor – but that it definitely doesn’t happen with a filmmaker as bizarre and challenging as Stanley Kubrick was, or with films this frank and mature about the confusing grey areas of adult sexuality and intimacy.

Karina Longworth, in her wonderful podcast You Must Remember This, recently did two seasons on ‘erotic’ cinema of the 80s and 90s, with a two-parter on Eyes Wide Shut as the capstone to that project. As someone who wasn’t old enough to be cognizant of the film or the media circus surrounding it in 1999, it was surprising to hear her go through the history and remember the frenzy surrounding the film’s production, with Hollywood tabloids seemingly expecting Eyes Wide Shut would be the hardcore-pornography-cum-prestige-drama Lars Von Trier would make with Nymphomaniac fifteen years later. What Eyes Wide Shut actually is – a film that is very much about sex, but is also very decidedly non-erotic – defies those prurient expectations in ways only Stanley Kubrick probably would: come for the steamy imagery hinted at in the marketing, stay for what is effectively is a 2.5-hour dream sequence about a crisis of masculinity. Christopher Nolan might have made a three-hour film about the creation of the atomic bomb a blockbuster hit, but he’s never tried bringing something like Eyes Wide Shut to theaters, and if he did, there aren’t any movie stars left with the capital to help make it happen (Cruise’s Mission: Impossible movies and Top Gun: Maverick are extraordinary and wonderful, but they’re also very much not the kind of adult, human drama he would do in the 80s and 90s).

Reports of the cinema’s death have been greatly exaggerated, and 2024 has had plenty of optimistic signs that nature may be healing; but Eyes Wide Shut is an idea of the cinema that no longer exists. It’s a sort of representative of that auteur-driven, Euro-centric, 20th-century vision of ‘What Cinema Is’ – what Dudley Andrew, in his 2010 book of that title, called the 70 or so years of feature films focused not on special effects, but on ‘revealing reality.’1 Or, as Martin Scorsese put it in his infamous 2019 New York Times opinion piece on Marvel movies:

For me, for the filmmakers I came to love and respect, for my friends who started making movies around the same time that I did, cinema was about revelation — aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation. It was about characters — the complexity of people and their contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures, the way they can hurt one another and love one another and suddenly come face to face with themselves. It was about confronting the unexpected on the screen and in the life it dramatized and interpreted, and enlarging the sense of what was possible in the art form.2

Eyes Wide Shut is the kind of film these writers were talking about. That it is, in fact, one of the final films of the 20th century – that its director died before that century could turn over to the new one – feels profoundly symbolic, especially looking back on it 25 years later. Kubrick was a director of the 20th century, his films the kinds of works we cinephiles and academic types think of when the capital-C ‘Cinema’ is invoked. I think those definitions can be unworkably narrow (particularly in Andrew’s case), but there is a romanticism to it all the same. A romanticism that also gives way to melancholy, considering the world of ‘cinema’ before and after Eyes Wide Shut: not because this specific movie changed that world, but because it came at a moment – a month after the release of Star Wars: Episode I, a year or two before The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter and Spider-Man forever changed the emphasis of mainstream Hollywood filmmaking – when the change was already in motion. Kubrick died suddenly, in the last stretch of post-production; Eyes Wide Shut was not consciously intended to be his farewell. But that is, of course, how it was greeted, and plenty of reviews at the time greeted it like a burial, a chance to put whatever high-minded, deliberate efforts Kubrick offered forever to rest (the word ‘slow’ was brandished around this film like a knife). Its reputation has improved, and the idea that it was a ‘burial,’ was ‘the end’ of something, has, I think, come to be seen as an important inflection point, symbolically if not literally. For a film full of symbols, perhaps that is appropriate; Eyes Wide Shut is a dream, in more ways than one – the dying dream, perhaps, of the imagined, platonic 20th-century cinema.

NEXT WEEK: We kick off December by celebrating the 100th anniversary of Buster Keaton’s classic SHERLOCK JR. Take a look at the entire December line-up below!

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Dudley Andrew, What Cinema Is! Bazin’s Quest and its Charge (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), xvii.