Revisiting "The Lost World: Jurassic Park" as the franchise turns 30

Bleak, sadistic, and utterly unhinged - I think I kinda like it

I revisited Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park over the weekend for the film’s 30th anniversary, and felt compelled to give another look to its immediate successor, The Lost World, which I don’t think I’ve seen since the days of VHS.

Steven Spielberg has many, many talents, but a natural affinity for sequels is not one of them. He’s made four in his career – The Lost World plus three Indiana Jones follow-ups – and none of them feel like projects he was entirely comfortable with, his instinct for pushing the envelope running headlong into the need to continue developing what worked before. Sometimes that gets you a Temple of Doom, which feels too dark and dangerous to properly satisfy one’s craving for more Raiders of the Lost Ark, and sometimes it gets you The Last Crusade, which feels like safe and familiar leftovers; both feature some tremendously skillful filmmaking, and both feel a bit less than the sum of their parts. I am fascinated by all of them.

The Lost World is definitely of a piece with his other sequels, then, in how it struggles mightily to figure out how to both innovate on and continue the first Jurassic Park, and in how genuinely virtuosic the filmmaking is when it fully revs up. Like Temple of Doom, large stretches of this film are deeply dark and unpleasant, a cold slap in the face to anyone entranced by the wonder and humanity of the first film, of which this sequel is mostly bereft. And also like Temple of Doom, it has some of Spielberg’s absolute best action set-pieces and razor-sharp technical direction, with a few profoundly deranged images and ideas in tow. It is an extremely messy movie, and one where you can tell exactly where Spielberg felt completely checked out – but you can also see where he perked back up. That dichotomy, present in all of Spielberg’s sequels, is the reason I can’t just easily write this one off; in fact, it animates my interest.

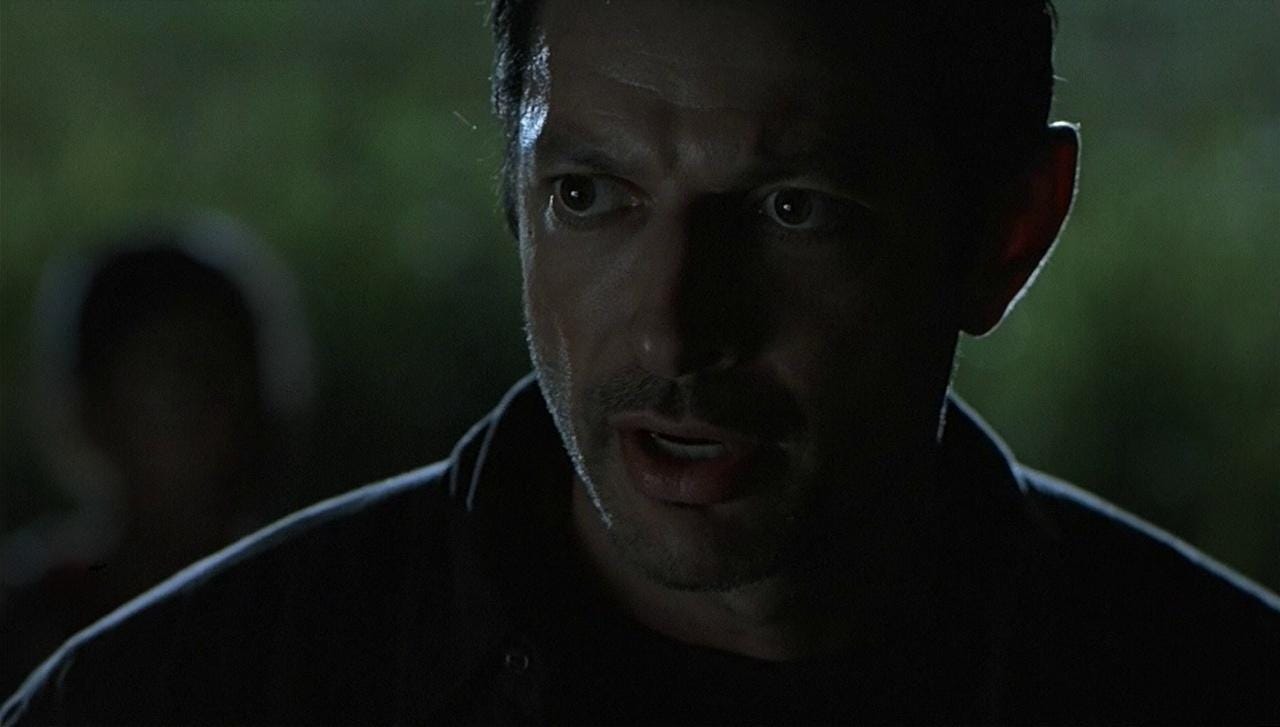

On the “Spielberg is checked out and nothing here works” side of things, the biggest failing of The Lost World comes where the characters are concerned – a problem exacerbated by the fact that the secret weapon of the original Jurassic Park was what a deep bench of vivid protagonists and great performances it boasted. The Lost World isn’t lacking for talent, adding the likes of Julianne Moore, Pete Postlethwaite, Peter Stormare, Richard Schiff, and Vince Vaughn, but other than the two returning figures played by Jeff Goldblum and, briefly, Richard Attenborough, nobody here ‘pops.’ I couldn’t tell you a single name between any of their characters. The film overloads on human antagonists, where the original had only one (Nedry, who was more of a greedy buffoon than an actively malevolent force), and while it sets up a potentially interesting dynamic where one under-resourced team has to defend the dinosaurs from a highly resourced group of capitalistic hunters, the characters around Goldblum’s Ian Malcolm are far too thin to create an actual character-driven back-and-forth, and Malcolm himself has no real convictions here other than “I told you so.”

Elevating Goldblum to the leading role here probably seemed like a no-brainer at the time; he is so ridiculously fun and charismatic in that first movie, his off-kilter energy and singular, syncopated phrasing channeled into making this rock-star mathematician feel like a real part of this world, and if there’s anywhere that first film errs, it’s in keeping Goldblum on the sidelines too much in the second half. The problem, though, is that characters come with their own points of view, and the point of view of your lead character colors the movie around them. Where the first Jurassic Park led with wonder, in part because that’s what was felt by our main characters – Alan, Ellie, the kids, Hammond, etc. – The Lost World leads with cynicism, because Ian Malcolm never liked this idea in the first place, and four years on from the events on Isla Nubar, he has nothing left for this project but suspicion and contempt. That’s a problem, and it sours the tone of The Lost World right off the bat when our main character shares none of the audience’s enthusiasm for the material. It’s a similar problem to what the later Pirates of the Caribbean movies ran into making Jack Sparrow the protagonist; it matters in Curse of the Black Pearl that our POV is aligned with two relatively normal people who see Jack the way the audience does – as a captivatingly bizarre wonder. When Jack gets the POV, the center of the movie is now his weird center of gravity, and nothing else can possibly be more interesting or attention-grabbing.

As great as Goldblum is, Ian Malcolm was a supporting character the first time around for a reason, and The Lost World neither understands why he worked so well before, nor how to replace the void left now that he is our center of gravity. The movie stocks up on cynical players with mercenary intent, and much of the first hour is devoted to watching a bunch of evil hunters chase and abuse a bunch of cool dinosaurs; it’s brutal and unpleasant, and Ian’s team isn’t vivid or passionate enough to provide a counterweight, fighting back less out of a sense of conviction than of obligation. At a certain point, the film loses even the pretense of interest in its characters, and in the second half, nobody, up to and including Goldblum, has much of anything to do other than be moved around as interchangeable players in the action sequences. The original Jurassic Park ends with several character-based denouements: Hammond hesitating before getting on the helicopter, then the quiet moment of Ellie watching the kids asleep on either side of Alan, as he watches the birds out the window, descendants of the dinosaurs they just left behind, a clear little piece of visual storytelling tying the themes of the movie together with the journey of the characters. The Lost World ends with Goldblum and Moore asleep on the couch, while Attenborough narrates some trifle about life finding a way – which wasn’t at all what this dark, violent film was about – and we literally never see Vaughn or Postlethwaite’s characters after leaving the island. There is an overwhelming sense that none of the human beings we’re looking at for these two hours matter one iota.

All that being said, and underlining that I think these problems hold The Lost World back from holding a candle to the original Jurassic Park…the second hour of this film really cooks. If you can feel Spielberg checking out from anything to do with story or character here, you can also feel that energy redirected in full towards the set pieces, and in terms of raw filmmaking prowess, there are large stretches of The Lost World that are absolutely astonishing. From the dual T-Rex attack on the RV, to the Velociraptors’ assault at the abandoned park site, to the completely bonkers finale in San Diego, The Lost World boasts incredibly elaborate sequences of action and tension that are positively drunk on creativity and technical ingenuity, realized with bold, bravura camerawork, jaw-dropping special effects, and a cartoon-esque precision of timing and impact. Viewed less as a sequel to Jurassic Park than as its own weirdly violent, uncomfortably sadistic monster movie, The Lost World actually has an awful lot going for it.

The RV sequence is the one part of the movie everyone seems to agree on, and for good reason. It’s extraordinary, an amazing symphony of tactile, intricate action and suspense, filled to burst with moving parts interacting with clockwork precision. An old-fashioned disaster movie, but with the collapsing location being dangled over the edge of a cliff, the whole thing is an obvious inspiration for similar sequences in later 21stcentury works, in both cinema and video games, from Uncharted 2 to Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning. The Lost World has quite a few elaborate ‘oners’, but my favorite such take comes as Schiff’s character gets the rope out of his Jeep, ties it around the tree, and then brings it into the RV and down to the team, all in one eerily fluid shot that fully lays out the spatial geography of the sequence, where all the moving parts are and how they interact. That Schiff’s heroism is then rewarded with the single most graphic death in either Spielberg-directed Jurassic Park film – being ripped in half by Mama and Papa T-Rex – seems on one level incredibly dissonant (the equivalent death in the first film is the scumbag lawyer, eaten after abandoning the children), but makes sense on this film’s own dark, sadistic terms, a necessary bloodletting after a sequence full of impossible escapes.

This scene and all the material in San Diego is incalculably aided by the quality of the dinosaur animatronics, which are off-the-charts amazing here. The baby T-Rex especially is an incredible effect, blending seamlessly with the humans and its surroundings, while the mother really comes alive in the third act. Plenty of CGI is employed, but whenever we’re up close on the face it’s a real animatronic or model, and there’s so much characterization poured into her expressions. I love the look she gives the camera when realizing Ian and Sarah have the baby in the car; it’s animatronic work subtle enough to suggest a dinosaur having a moment of dawning realization, and maybe even panic. In that moment, the character feels more human than any of the people on screen.

There is also some truly inspired material in the big raptor attack on the island, with that particularly amazing overhead shot of the raptors executing a pincer movement on the humans in the tall grass. Ian, Sarah, and Kelly’s battle with the raptors in the abandoned park space reaches full-on Looney Tunes levels of goofy kinetic action – Kelly using her gymnast powers to kick a raptor through the window and impale it on rebar outside is a deliriously awesome image – and features another set of gasp-inducing oners including a long back-and-forth between Ian and a CG raptor choreographed with all the musical flair Spielberg would bring to West Side Story 25 years later.

And I’m not going to lie – I love the T. Rex coming to San Diego. I love the boat crashing into the harbor, and all the quiet, careful build up to the moment (it’s King Kong, if King Kong got loose before they landed). I love the lunatic iconography of the T-Rex stomping through the immigration checkpoint and declaring its intention to take the big city by storm. I love Rexy stomping through a suburban neighborhood like it owns the place, drinking out of the pool and growling at the dog to back off. It’s all incredibly goofy, but passionately so. It feels like Spielberg stomping a big toy dinosaur through a LEGO set and cackling at the chaos. I see Sammy Fabelman playing with his train set and getting obsessed with the idea of filming its destruction. This is Spielberg cutting loose, making lemonade out of a film that, with a script this rough, was mostly giving him lemons.

I will also give the film this: it has one of the greatest match cuts in film history. You probably know the one: The mother screaming on the beach as her child is mutilated by dinosaurs, cutting to Ian yawning against a beach backdrop on the subway, with an auditory match as well between her wail and the roar of the train coming in. It is absolutely brilliant, as perfectly teachable an example of the technique as the bone-to-satellite in Kubrick’s 2001, and while it isn’t as pregnant with meaning as that all-time classic moment, it does feel like something of a rosetta stone to understanding and enjoying the strange pleasures of The Lost World: A brilliant man yawning while a women screams at an abject, over-the-top horror, a moment of unimaginable violence turned seamlessly into a visual gag. It is sadistic and unfeeling, jarringly negating the humanity of the moment and turning it into a different kind of gonzo cinematic pleasure entirely.

That is The Lost World in a nutshell – either uninterested in or incapable of recapturing the essence of its predecessor, punishing the audience for expecting something similar, and rewarding us instead with ridiculous visual invention. I don’t know if it’s what I wanted, but I am, on the whole, glad we have it, and that’s more than I can say for any of the increasingly detestable sequels that came after. Even when he doesn’t really want to be there, Spielberg is in a class of his own.

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our sister series about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Explore our archives and subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all podcasting platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com