The Top 10 Films of 2025

A very bad year full of very good movies

My instinct, as I sat down to start planning my annual Top Ten list, was that 2025 had been in some way a ‘lesser’ year for film, one with plenty of good movies but without a particularly high density of great ones. But when I actually started writing things out, I found myself faced with a much longer list of contenders than I’d expected, one I found very difficult to narrow down, let alone to rank. In the end, I’m left with a top ten I feel extremely passionate about from top to bottom, and a second-ten list of ‘runners up’ that I would be nearly as enthusiastic about on its own if the first ten never existed.

So maybe 2025 was a good year for film. It might just have been difficult to appreciate it in the moment, since 2025 was such a nightmarishly terrible year in most other ways, to such a degree that I may not have recognized how much I leaned on this year’s great cinematic art to help me through it. Given my new full-time teaching job at CU Boulder, I didn’t write as many full-length movie reviews as I would have liked this year. But when I did, they were in every instance just as much about processing news and politics as they were about the films themselves. And I don’t think that’s wrong: it is not in fact possible to analyze movies objectively, or to analyze them with some mythical ‘view from nowhere.’ Films are made in a particular context, and we watch them in a particular context; good film reviews are honest, and honest reactions to art speak to the way they serve as prisms for everything we take with us into the theater. In 2025, those prisms reflected multitudes. The films, as always, speak for themselves, and they tell the story of this year in powerful, clarifying fashion.

The ground rules, as always: A ‘2025 movie’ means a film that made its commercial debut in the United States in 2025, either theatrically or on streaming. Some of these films are listed as 2024 releases on sources like Letterboxd or IMDB because of festival or overseas debuts, but they are 2025 movies as available here in America.

So without further ado, let’s begin with 10 great films that didn’t quite make the cut:

Part I: Honorable Mentions (#20 – #11)

20. It is inconceivably shameful that Warner Bros. didn’t proudly release The Day The Earth Blew Up: A Looney Tunes Movie (Dir. Pete Browngardt) themselves, since it is the triumphant culmination of something Warner Animation has been striving to realize for decades now: an honest-to-God feature-length Looney Tunes cartoon. This team – who cut their teeth on the Looney Tunes Cartoons series for HBO Max, the best and truest-to-form use of these characters since the Chuck Jones/Friz Freleng heyday – finally cracked the code, focusing on the right set of character (Porky Pig and Daffy Duck) and telling just enough story, with just enough characterization, to give these 90 minutes a shape and structure, without ever letting the form overwhelm the key goal of the Looney Tunes, which is zany, irreverent comedy. Every time the film threatens to get a little too conventional, it takes a crazy zag, does a big silly joke, and proves it knows exactly what it’s doing. The animation is gorgeous, the score a big sweeping orchestral ode to a century of Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies musical history, and there isn’t one single ounce of irony or cynicism to any of it. This is a film WB should have embraced with pride and fanfare; at least Ketchup Entertainment stepped in to give it a day in the sun, and we’ll get another rescue mission from them in 2026 with Coyote vs. Acme. Say it with me, everyone: Fuck you, David Zaslav.

19. One could correctly accuse Bong Joon-ho’s Mickey 17 of being a mess, and I would rejoinder that I honestly don’t care. The opportunity to spend two hours inside Bong’s singular mind is a hell of a gift, and even if Mickey 17 is unwieldy in the sheer number of ideas at work, I love watching those ideas play out. It’s a much stranger, sadder, and more complicated film than one would think based on the marketing: zany in some places, and deeply introspective in others; bombastic in certain sequences, and painfully intimate in others; does social commentary with zero subtlety sometimes, and a lot of complexity and challenge elsewhere. Whenever you think you’ve got it pinned down, it has something else to say. And if it is ‘messy’ – well, maybe figuring out how we live under the violent regime of capitalism with joy and purpose and without guilt is also a messy process. It’s an honest mess, one that no other director would make quite the same way. And no one but Robert Pattinson would give the specific performance(s) he gives here, with the swing-for-the-fences cartoon accent he so endearingly embraces. This is, for good and for ill, a totally singular film, an expression of immense thought and personality realized on a giant canvas with big studio resources. Thank god for Bong – we’re never going to be able to print out a copy of him. He’s one of a kind.

18. Wes Anderson cannot be stopped, somehow becoming more productive than ever 30 years into his career. The Phoenician Scheme, his fourth feature of the 2020s so far, is probably my least favorite of his recent run, but still an undeniable treat: a deeply silly movie that at times feels like the Anderson equivalent of a Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker film, a la Airplane! or Top Secret (bizarrely enough, this wouldn’t make a bad double-feature with this year’s excellent The Naked Gun reboot). It might be Anderson’s single funniest film to date, which is saying something, bolstered by an endearingly straight-faced performance from Benicio Del Toro – who sings Anderson’s dialogue as well as anyone ever has – and a dynamite oddball turn from Michael Cera, in one of two completely scene-stealing roles the actor filled this year (the other coming in Edgar Wright’s otherwise disappointing The Running Man). And while The Phoenician Scheme arguably lacks a moment like the Margot Robbie scene in Asteroid City, where the entire film snaps into exquisite focus with a big thematic punch, there is still a rich vein of pathos undergirding the comedy here, with the very last scene – in which Del Toro’s Zsa-Zsa Korda and his daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton, impressing in her first lead role) enjoy each other’s company amidst their newfound poverty – providing the kind of touching, deeply human cap that ultimately animates all of Anderson’s singular theatrics.

17. I get the criticism of Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, which is a less propulsive or structurally elegant film than Christopher McQuarrie and Tom Cruise’s other spectacular entries in this series. The first hour is unwieldly and overburdened, certain threads from 2023’s Dead Reckoning go unresolved, and neither the inhuman evil of ‘The Entity’ nor the embodied antagonist Gabriel (Esai Morales) come together as coherently as they should. What’s undeniable, though, is that when The Final Reckoning is fully engaged, it is an astonishing cinematic feat to behold. Ethan’s long-promised journey to the Sevastopol submarine results in perhaps the greatest extended set-piece in a franchise notoriously full of them, a formal masterwork of desperation and suspense so adroit at visual storytelling that exactly two words are spoken in the entire sequence. And it’s ultimately just the preamble for a grand finale in which Cruise and McQuarrie pull off one of the single most eye-popping stunts in cinematic history. When I walked out of the theater, heart still racing and breath still short from the truly next level kineticism on display, I felt the magic of this series in full force, recontextualized as a messily exhilarating goodbye. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

16. Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind is the single most mid-century-French-ass movie I’ve ever seen produced in the English language, and I mean that as a compliment. It’s got a lot of Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket in it, particularly in its final scene; some of Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows, especially in its irresistible jazz score by Rob Mazurek; and some of Agnès Varda’s Vagabond, in the tactile, wintry wanderings of its second half. It’s that kind of crime drama that is absolutely thrilling and unbearably tense when depicting the planning and execution of a robbery, but in its totality turns out not to be a crime drama at all, but a very internalized story about an individual on a long dark night of the soul, the crime just one external expression of the many ways he’s being eaten alive from the inside. It’s the kind of movie where we spend as much time watching Josh O’Connor (in the midst of a banner year of performances) moving around a small hotel room, hanging up his shirts and sadly eating a sandwich, as we do on the actual implementation or fallout of the crime. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that eating the sandwich in the hotel is the fallout of the crime, in the same way Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless spends a lot of time going in circles with Jean Seberg in hotel rooms because the crime he’s already committed means he has no future, and is just killing time in purgatory. But at no point is the film just a pastiche; it’s just so authentically good at building off its inspirations, within the already robust framework of Reichardt’s own distinctively slow and lived-in style, that moments of cinematic communion across time and space catch the viewer off guard.

15. It was never really in doubt that James Gunn would get Superman right, since nobody in the post-Marvel era of Hollywood superhero adaptations has shown a deeper or more passionate understanding of comic book heroes and what makes them tick. Yet the clarity with which is Gunn is able to identify what makes Superman special – and why he frankly matters more than ever in 2025 – still took me aback. This is a tremendously fun, deliriously entertaining piece of pop-culture myth-making, awash in striking, colorful imagery, alive with humor and pathos and actual honest-to-God romance, and bursting with characters I’d never heard of before who became personal favorites by the time the end credits roll (Edi Gathegi in particular steals the show as Mr. Terrific). But it is also the most politically pointed superhero movie of the modern era, a film about the targeting of immigrants and extralegal abuses of the state, the horror of watching power consolidate in the hands of sadistic sociopathic tech billionaires, and the bloody spectacle of watching political superpowers conspire to destroy vulnerable minority populations abroad. This is a Superman film which understands that Superman must stand for something, and it thus feels, in ways superhero movies so rarely do, like a film we truly need right now, not just because it is so fun and entertaining as cinematic escapism, but because it genuinely engages with those aspects of the world that make us want to escape in the first place. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

14. Sometimes when a great filmmaker spends their whole life thinking about and working towards one movie, it comes out pre-digested, overthought and overwrought. Not so with Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, a film through which passion flows from first frame to last. Animated by del Toro’s reliably stupendous production design and several incredible performances – with Jacob Elordi in particular announcing himself here as a major actor – this is a Frankenstein which breathes along the way, luxuriating in its storytelling, allowing its ideas to arise through the characters and the drama. It could also be called “The Catholic Frankenstein,” for just how in tune it is with the religious themes of the story, and how deeply felt are its emotions of rage, sin, and redemption. Del Toro’s Victor Frankenstein does not want to disprove God, but to thumb his nose at the divine, understanding his own fury by enacting celestial cruelty upon the world. And of course, the brilliance of this story is that his creation proves so much better than him, so much more willing to forgive, to live, and to love. The film’s final scene, in which Victor implores the Creature to “forgive yourself into existence,” the Father acting as both a parent and a confessor, the Creature as both a child and a Priest taking his confession, is one of the great movie moments of 2025, and a high point of del Toro’s career thus far. You can listen to our full podcast review of this film on Purely Academic at this link.

13. Rian Johnson’s latest (and hopefully far from last) Benoit Blanc mystery, Wake Up Dead Man, is a darker, slower, and more thematically dense film than Knives Out or Glass Onion, and it may be a touch less ‘entertaining’ as a result: less overtly comedic (though there are still some mighty big belly laughs), less oriented around big movie star personalities bouncing off one another (though there are still plenty of fine actors doing outstanding work), and quite literally less ‘colorful’ in its visual palette (though Steve Yedlin’s cinematography is still a tactile wonder to behold). But Wake Up Dead Man is no less enthralling, and its ideas are quite a bit bigger and more challenging. Where Knives Out and Glass Onion felt like they were taking place in a universe a few degrees off from our axis, in a world where someone like Blanc could meaningfully set things right, Wake Up Dead Man feels much more like Blanc has walked out of his world and into ours, a world where his Kentucky-fried charm isn’t enough to fully soothe the spirit, and in which his ability to put the pieces together doesn’t actually do anything to repair the cracks in this society. And this time, he isn’t paired with an underdog outsider, but with another figure of moral authority in Josh O’Connor’s Father Jud. The Detective teams up with The Priest, literally and archetypally, and by putting Blanc in conversation with religion, Johnson also questions the very limits of the Whodunnit genre in the here and now. The result is one of the richest and most rewarding films of the year, and one of the best films about or involving faith Hollywood has produced in living memory. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

12. One of the year’s biggest success stories, Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Infinity Castle (Dir. Sotozaki Haruo) is a wholly unique blockbuster, one filled with some of the most spectacular visuals and impactful animation one will ever see, but which is ultimately more interested in the interiority of its characters – even and especially its demonic villains – than it is in mayhem and bombast. It works not only because ufotable executes at such a ridiculously high bar from moment to moment, assisted by an absurdly stacked Japanese voice cast that tears into every line with spine-tingling aplomb, but because the studio finds such rich thematic connections in Gotouge Koyoharu’s manga source material. This series has become a history-making global sensation for good reason, and it delights me to no end that a film as beautiful, brutal, poignant, strange, and singular as this one has shattered every commercial record and expectation for non-American animation. This is ‘event cinema’ at its most rewarding, and it’s only the beginning of the end: as manga readers know, the best is very much yet to come. Given their track record so far, it’s tough to imagine just how high ufotable will soar when they get there. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

11. You will pry dystopian stories about children forced to play deadly games for public amusement from director Francis Lawrence’s cold, dead hands. But the thing is, the longer Lawrence clings to these tales – from four Hunger Games films to this year’s The Long Walk – the more history validates his interest in telling them, and the better he gets at making films that rise to the moment. 2023’s Hunger Games prequel The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes was already a huge leap forward for both Lawrence and The Hunger Games series, and The Long Walk genuinely bowled me over. These films are deeply felt and righteously angry, using the language of pulp, popular fiction to deliver furious roars of human compassion. This adaptation of Steven King’s 1979 novel, in which a group of young men selected from all 50 states must walk across the country until only one survives, is a brutal, challenging, and often darkly beautiful exemplar of dystopian storytelling, driven by outstanding performances from a large young cast, with particularly extraordinary work from David Jonsson. As with Ballad before it, The Long Walk ends on such a bleak and uncompromising note – expressing how the brutality of life in an authoritarian system can eventually corrode the heart of even the best among us – that I’m surprised it got through the Hollywood studio system intact. When the period of 2020s Hollywood history is written, and in particular how this era intersects with the politics of our times, I think Lawrence’s recent work is going to have a serious role in that conversation. In a time of aggressively ‘apolitical’ art (which really just means ‘political, but in service of the oppressors and their violent status quo’), Lawrence is actually using Hollywood’s money to express very real anger and grief.

Part II: The Top 10 Films of 2025

10. Avatar: Fire and Ash

Directed by James Cameron

Look, is it possible I’m putting this film on my Top 10 to thumb my nose at everyone acting holier-than-thou about it and continuing to insist that three of the most widely seen films of my lifetime ‘have no cultural impact?’ I cannot in good conscience say the answer is ‘no.’ I am only human. A certain amount of pettiness rages inside of me, as it does in you.

But the real reason has more to do with the fact that I first watched Avatar: Fire and Ash on December 18th, I am writing this on January 4th, and not a day has passed in that interim that I haven’t found myself thinking about one of the many weird and wonderful images, ideas, and/or moments that happens in this absurdly long fever dream of a movie. As I said in my initial review, this is an imperfect and ungainly beast of a movie, though I think subsequent viewings have revealed more careful structuring at work here than I first gave the film credit for (it’s no mean feat that the last hour traces and resolves individual arcs for at least ten different major characters, criss-crossing through a massive battle being waged in the air, on the water, under the water, and within the eye of God). But even if Fire and Ash is a less distinctive triumph than 2022’s The Way of Water, it’s this one that’s made me admit I am, in fact, a fan of these movies, mainly because of how singular and authorial they are. The Avatar films are at once highly conventional on the level of basic plot structure and character archetypes, yet also profoundly weird and idiosyncratic in terms of actual substance and incident. They are wholly earnest, heart fully dangling on the sleeve, in a time when irony-poisoned cynicism is the coin by which most expensive Hollywood productions trade. They are technically peerless visual marvels, operating at a level of VFX wizardry that feels like it’s being beamed in from many decades in the future, but the images they conjure carry the immediacy of a vivid dream and the hungry enthusiasm of a genuine passion project. In an early sequence with the Wind Traders, Cameron incorporates an image he first drew as concept art in 1978, a full 48 years ago, at the age of 24. For many filmmakers, that image alone could be the whole movie, justification enough to fill an entire film and then some. For Cameron, it’s one visual idea in the first act of his third Avatar film, a movie which goes on to show us many equally rapturous marvels before it rolls credits.

Put simply, I just love what Cameron is doing here. I love what a big canvas he’s painting on. I love how dense this film is with ideas, how even at nearly 200 minutes it never feels like it’s running low on new things to throw at you. I love how many big questions it stealthily gets us thinking about, from matters of faith to the corrupting influence of firearms to the transhumanist quandary of Col. Miles Quaritch finding himself increasingly committed to the well-being of the son who was born before this incarnation of his own body and mind ever existed. I love how Cameron is willing to use those broad archetypes he started with to make some truly bold swings (like the show-stopping ‘binding of Isaac’ scene between Jake, Neytiri, and Spider). I love how weirdly horny this movie is, with Varang and Quaritch being so turned on by one another’s freak that there’s an entire extended sequence devoted to the two getting high, making war plans, and getting it on. I love how rich I find the characters and their environment at this point, and that Cameron is telling a true generational tale here, in the way Star Wars has vaguely gestured at but never really committed to. I chuckle to myself at least once a day remembering the moment when Quaritch casually struts into a military briefing in full Ash People warpaint, practically daring a bewildered Edie Falco to say something about his frankly out-of-control midlife crisis. I love that Cameron makes the simultaneously wacky and breathtaking choice to personify Pandora’s God, Eywa, via an homage to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. I love being proven wrong about Sam Worthington, who seemed like an empty vessel, a placeholder movie star, back in 2009, and has turned out to be a remarkably soulful and effective performer in middle age. I love how Quaritch exits this movie by plummeting straight towards the camera and bellowing in defiant rage. And I love that we get all of that and more in a movie that also has awesome space whales debating ethics and politics in big goofy yellow subtitles, before tearing shit up in the climax.

More than anything, I love that Avatar: Fire and Ash so palpably feels like the work of a director and creative team who are hugely artistically invigorated, and are pulling us into the fun of exploring cinematic possibilities with them on this impossibly vast scale. There are a lot of dynamics at work right now that make it feel like American cinema is in its death throes, from endless corporate consolidation to Netflix’s war on movie theaters to all the lifeless, concrete-colored live-action remakes of vibrant, beloved cartoons. But when I’m the theater getting lost in the world of Pandora, those thoughts are very far from my mind, because the cinema in front of me feels so gloriously alive.

Avatar: Fire and Ash is currently playing in theaters everywhere. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

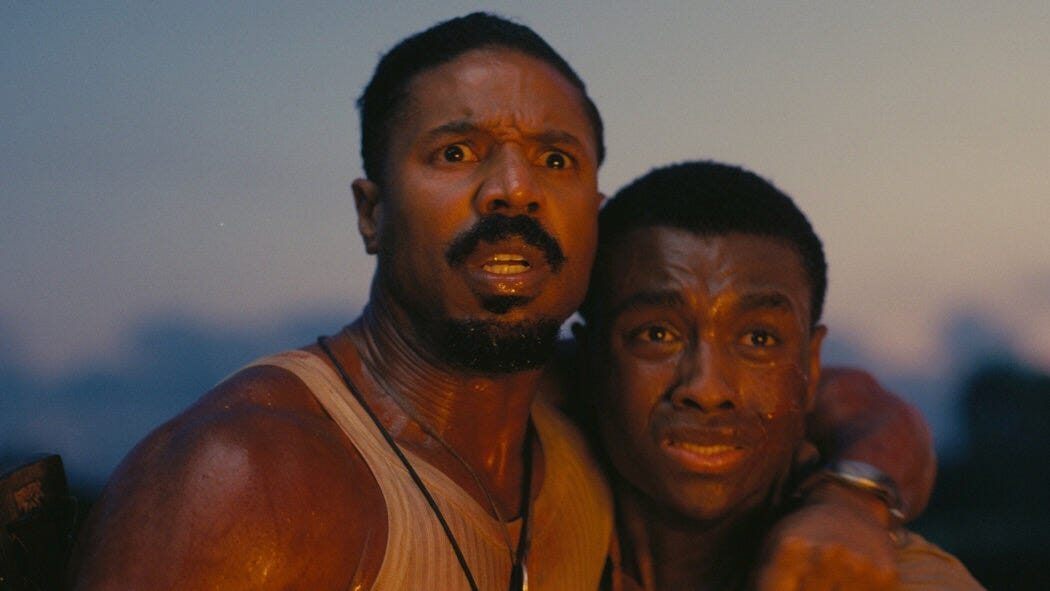

9. Sinners

Directed by Ryan Coogler

Sinners is the kind of wide-ranging, ambitious, beautifully unwieldy auteur piece you only get when a director has a massive success – as Ryan Coogler did twice with Black Panther – and then cashes in all their chips on one giant risk. There’s a go-for-broke sensibility to movies like this, where one can sense the director worrying they may never again get to paint so freely on such a big canvas, so they paint as much as they can. Sinners is at least two or three different movies, with at least two or three distinct endings, and its ambitions and artistic prowess are such that it’s already given the audience a full three-course cinematic meal by the time the vampire action gets underway in the second hour. I’ve seen the film twice, once on IMAX and once on 4K Blu-ray at home; both were extraordinary aesthetic experiences, given the expansive, enveloping mix of tall IMAX 70mm and extra-wide Ultra Panavision 70 film formats, all shot with an amazing eye for space, atmosphere, and detail by Autumn Durald Arkapaw, every frame populated with deeply lived-in imagery from production designer Hannah Beachler and costume designer Ruth E. Carter (both among the best in their fields, both former – and almost certainly future – Oscar winners on Coogler projects). On each viewing, I walked away unsure if or how the entire film holds together – and equally sure that I didn’t care.

I give a lecture on Coogler’s original Black Panther every year at CU Boulder, for which I’ve read and re-read a lot of interviews with the director, and you can tell from first frame to last that Sinners is all him – all his fascinations and thematic preoccupations in one place, an enthusiastic mash-up of periods, genres, and tones. It uses horror iconography in ways that feel prickly and challenging and difficult to disentangle, and it’s impossible to neatly map the film’s narrative into a tidy metaphor or allegory. Its ending comes in several stages and the film starts folding back in on itself in these very fluid, sensual ways down the home stretch. Despite the genre trappings, the film is principally interested in music – where it comes from, how it moves us, where we take it as our lives go on – with Coogler and Ludwig Göransson’s always remarkable partnership here reaching new heights as they engage with over a century’s worth of American music and its antecedents. It all culminates in an already-legendary sequence shot at the film’s midpoint, where a single blues song summons the past and the future of multiple races, lineages, and legacies together under one roof. That shot alone is the best thing Coogler has yet done as an artist, and in and of itself has a little bit of everything else he’s ever done inside it.

In short, Coogler took his blank check and got aggressively creative with it, making a movie that’s absolutely overflowing with great ideas, images, and sounds, that isn’t afraid to go big, to let contradictions and challenges exist in productive tension. Sinners is provocative, heartfelt, and singular in the way ‘big’ Hollywood movies so rarely are, and in making it, Coogler has put himself on the same career trajectory as Christopher Nolan: a filmmaker who played the studio franchise game just long enough to earn a passion project, then proved their own original creativity and craftsmanship was more than enough to get butts in seats. In a year full of bad news for the future of movies, Sinners is a rare symbol of hope.

Sinners is currently streaming on HBO Max, is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and is also available on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K UHD.

8. 28 Years Later

Directed by Danny Boyle

28 Days Later, released 23 years ago, was a special and singular movie, one of the unassailable highlights in the careers of both its writer, Alex Garland, and director, Danny Boyle. With 28 Years Later, they have come back to the material – alongside the great cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, one of the first true giants of digital filmmaking – and made a movie that isn’t much at all like its turn-of-the-century predecessor, except in the ways it is also abstract, protean, and deeply felt, a zombie survival film that’s really a challenging, strange, somewhat experimental human drama. With another quarter-century of maturity under their belts, Boyle and Garland return to the material as better filmmakers and storytellers capable of even deeper and bolder explorations. This is a better film than the original, one a touch more ambitious, beguiling, and profound in all dimensions.

The film follows a 12-year-old protagonist, Spike (Alfie Williams, in one of the great child performances of recent memory), living on a small island colony within the quarantined United Kingdom. In its first half, Spike learns about killing from his father (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, possibly doing career-best work), and in the second, he learns about dying from his mother (Jodie Comer, brilliant as always). They are two sides of a greater coin called ‘living,’ a process he can only begin to comprehend after making these two consecutive journeys. Where 28 Days Later was a young man’s movie, a statement about the desperate and beautiful purpose of living and loving in defiance of a broken world, 28 Years Later reflects the aging of its creators: it is a film about death and dying, frank and mature in its confrontation of life’s ultimate destination, and resolute in its refusal to see that natural end point nihilistically. Here is a film that finds real beauty in a sea of corpses, and in the act of adding the remains of another loved one onto the pile. Ralph Fiennes shows up as our guide here, spending his entire appearance slathered in iodine and usually holding at least one severed human head; somehow, he comes across as the most sane and empathetic character in the film. It is all ridiculous, and it is all profound, and watching it all unfold eventually reduced me to tears.

This is what a sequel should be: not a mere extension or repeat of the original, nor an easy call to the nostalgia centers of our lizard brains, but a bold new work that uses that earlier creation as a springboard for further ideas and greater, more challenging artistry. Boyle and Garland are not done yet, as 28 Years Later is the first entry in a planned trilogy, with the second part – The Bone Temple – debuting in theaters just a few days from now. But however the larger project turns out, 28 Years Later works entirely on its own terms, and at no point feels like an exercise in crass brand expansion. Even the final scene, which certainly seems to tee up the next stage of this story, absolutely works within this film’s specific emotional and thematic context. Violent, bizarre, and darkly funny, it plays like one more statement on the way the world seems to get bigger and stranger once one goes out and starts living in it.

28 Years Later is currently streaming on Netflix, is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and is also available on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K UHD. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

7. Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc

Directed by Yoshihara Tatsuya

Of every film on this list, this is the one that surprised me most. After seeing it, I finally went back and started reading the Fujimoto Tatsuki manga on which the Chainsaw Man anime is based, and found it to be an absolute revelation: not just for the quality of the paneling, or for the sketchy, idiosyncratic, palpably handcrafted drawings, but because of the way this story that could so easily feel absurd – a boy who hunts ‘Devils’ by pulling a cord in his chest to extend giant chainsaws from his face and arms – is instead shot through with such a quiet, pervasive sadness. Protagonist Denji’s coming-of-age journey embodies the daily grief of adolescence – especially one impacted by abuse and poverty – in ways few stories in this mold ever do. And in hindsight, this is why the 12-episode first season of MAPPA’s anime adaptation from 2022 felt a little weightless to me. A lot of those tonal and atmospheric intangibles in Fujimoto’s manga were lost in the translation from page to screen, an example of how you can adapt every moment and word of a story, and in moving from one medium to another lose some part of the essence.

The Reze Arc film loses absolutely none of it, and in fact builds on and deepens the greatest qualities of its source material in the way the greatest adaptations do. With Yoshihara Tatsuya elevated from the first season’s ‘action director’ to the film’s chief creative, there is a palpable artistic transformation here. The first half, as Denji and the eponymous Reze have their sweet teen romance, feels like it could be a Kyoto Animation movie, and not just because Ushio Kensuke’s piano score – the first of two films on this list he composed for – sounds straight out of A Silent Voice. The film’s entire storyboarding style recalls Yamada Naoko or Ishihara Tatsuya, in the off-kilter framings and quiet cutaways to the surrounding environment as the characters get to know each other. It is such a lived-in, sensual, and spatial way of depicting the world and the characters’ emotions that if the film were just a straightforward teen romance, it would still be one of the year’s best films. But of course, things eventually go sideways, and when the enormous action spectacle of the film’s second half arrives, it positively rips the roof off. We are in a Golden era of amazing Shōnen battle animation these days, from ufotable’s work on Kimetsu no Yaiba, to Toei’s remarkable rejuvenation of One Piece, to the killer fantasy action of A-1 Pictures’ Solo Leveling, to MAPPA’s own thrilling adaptation of Jujutsu Kaisen. So the highest praise I can give the climax of Reze Arc is that it looks, sounds, and feels like nothing else the medium is doing right now, playing with form and style in countless adventurous ways, and even pushing into total visual abstraction. When you put the two halves of the movie together, there’s an amazing call-and-response quality to the whole experience, as the quiet, internalized emotions of the first half become the fuel that ignites the maximal expressionistic thrill ride of the second.

In fact, the film is a model of cinematic structure in all sorts of ways, proving itself a perfectly teachable example of the ‘kishōtenketsu’ four-act structure. In that model, the last part – the ‘ketsu,’ which literally means ‘tying together’ – is when a story pulls taut its narrative and thematic threads into a unified knot. The last ten minutes of the Reze Arc film do this as powerfully as any movie in recent memory, both in the melancholy sweetness of a final scene between Denji and Reze on the beach, and in an absolutely cutthroat final beat back in the city that lands its gut punch with disarming weight. This is a film full of incredible parts, and in the end, it proves itself even more than the sum of them. There have been many excellent anime franchise films so far this decade, but this is among the very best, not only continuing and expanding upon an ongoing story in ways that make the entire project seem more exciting, but standing tall as a truly great film entirely on its own terms.

Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc is currently available to buy and rent on digital retailers.

6. The Colors Within

Directed by Yamada Naoko

Yamada Naoko is the most preternaturally gifted director of Japanese animation to emerge in the 21st century. She’s an honest-to-God prodigy who revolutionized TV anime before turning 25 with the 2009 series K-On!, and quickly developed one of the most distinctive and effective eyes for storyboarding – for visual composition and editorial pace – in the history of the medium. She is interested in people who feel like they’re on the outside looking in: people who feel some kind of disconnect, some inability to socialize the same way as ‘normal’ people (which is why her films are so open to queer and/or neurodivergent readings). And her stories are about those people finding somebody or something that takes them out of that shell and makes them come alive. Usually that’s through music – crafted in concert with Yamada’s brilliant regular composer, Ushio Kensuke, though typically with lyrics provided by Yamada herself – because music can express so much more than words, in much the same way animation can express more of our internal worlds than live-action photography.

Her latest film, The Colors Within, returns to familiar narrative territory for the director – high-school students forming a band – but it arguably distills who Yamada is as a filmmaker in more concentrated fashion than ever before, in part because it is so stripped down, her ‘smallest’ and most deeply internalized work next to 2014’s Tamako Love Story. Calling the film ‘deeply felt’ would be selling it short, because ‘feelings’ are what the entire film is about, from start to finish and at every single moment in between. Working as always with Yoshida Reiko – the wildly prolific screenwriter who has penned every production Yamada has ever been in charge of – The Colors Within is not a story about a life-changing moment for its characters; nobody actually leaves the movie headed in a different direction than they were when it started. But they better understand themselves, their decisions, and their emotions, and in the world of Yamada Naoko, that glacial change feels positively seismic.

Visually, The Colors Within is a stunningly beautiful production, adroit at finding poetry in the mundane through acute attention to sensory detail, and transcendent when it illustrates the synesthesia through which its main character experiences and interprets the world. It includes some of the quietest, most intimate movie moments of the year – an illicit sleepover in a boarding school dorm room, a night spent making music in an abandoned Church while it snows outside – and they are also some of the most unforgettable. It all comes together in the film’s climax, an unbroken three-song concert sequence, that is every inch as great and impactful a stretch of filmmaking as anything else released this year. It’s easy to take what Yamada and company achieve here for granted, as the music sounds so authentic to these teenage characters and what they might write, and because the animation is absolutely frame-perfect in depicting musical performance. But those songs didn’t write themselves, and instruments are famously one of the hardest things for animators to authentically depict (and The Colors Within sets itself the additional challenge of including a theremin in the mix). But the sequence’s real artistic coup lies in its ability to set up all the film’s emotional pins in such a way that it can then knock them down in a ten-minute climax that is entirely devoid of dialogue. To have such a sequence play out in such arresting fashion, and have it all be fully legible and profoundly impactful as a resolution to three intertwined character arcs…well, that’s magic. That’s why Yamada is, in fact, the most preternaturally gifted Japanese animation director of the century thus far. And it’s why The Colors Within is, in all its quiet, unassuming glory, absolutely essential viewing.

The Colors Within is currently streaming on HBO Max, is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and is also available on DVD and Blu-ray. You can listen to our full podcast review of the film on Japanimation Station at this link.

5. No Other Choice

Directed by Park Chan-wook

One can describe the ‘plot’ of Park Chan-wook’s latest in a simple sentence: an out-of-work family man devises a plot to kill off his competition for a new job. But this logline captures absolutely none of the film’s remarkable style and substance, which is so beautifully strange and infectiously delirious in its creativity. Nobody else makes movies that are at once so absurdly funny and so righteously furious, and if No Other Choice is a career high-point for the South Korean auteur, it’s because both halves of the Park Chan-wook equation are dialed up so very high across these two hours. No Other Choice is brilliant, brutal, and biting satire as only Park could make it.

On the level of craft, No Other Choice is second-to-none for 2025. The way Park moves the camera here – and the way he frames for impact, interrogation, and astonishment – is consistently virtuosic; the way he cuts between images to suggest larger ideas, with the force of a Soviet-styled sledgehammer, continually took me aback; the lyrical transitions he frequently employs, with parts of separate images melting into one another like they’re forming in the mind’s eye in real time, is just plain humbling. And the use of music – both original and needle drops – is next-level stupendous, with one extended sequence in particular serving as perhaps the greatest use of music and sound design in any film this year.

The film takes as its starting point the Marxist critique that capitalism feeds on the production of intra-class competition, but spins out so widely and wildly from there, its study of economic anxiety quickly broadening into a comedy about violence and the performance of masculinity, providing some incredibly audacious laughs and heaps of loaded, unforgettably ersatz imagery before transforming, absolutely seamlessly, into something much sadder and more contemplative in its closing minutes. Ultimately, Park has made one of the definitive cinematic statements on the way capitalism encourages us to not only be our worst selves, but to willingly sacrifice our humanity on the altar of class and status. And even at the very end, Park is, as always, unwilling to trust himself or his audience with the production of one simple reading: there is a split personality to the final minutes of No Other Choice, an elegy for a world that once had space for human beings, and an acknowledgment of the very human reasons we offer up our hearts on silver platters to those with the means to make us comfortable. The words “No other choice” (or, at least, their Korean equivalent) are littered across the dialogue of this movie; if Park wants us to take any one idea away from this, it’s that this phrase is always and irreducibly a lie - a lie we are taught young, and continually incentivized to never wrench ourselves away from.

No Other Choice is currently playing in select theaters.

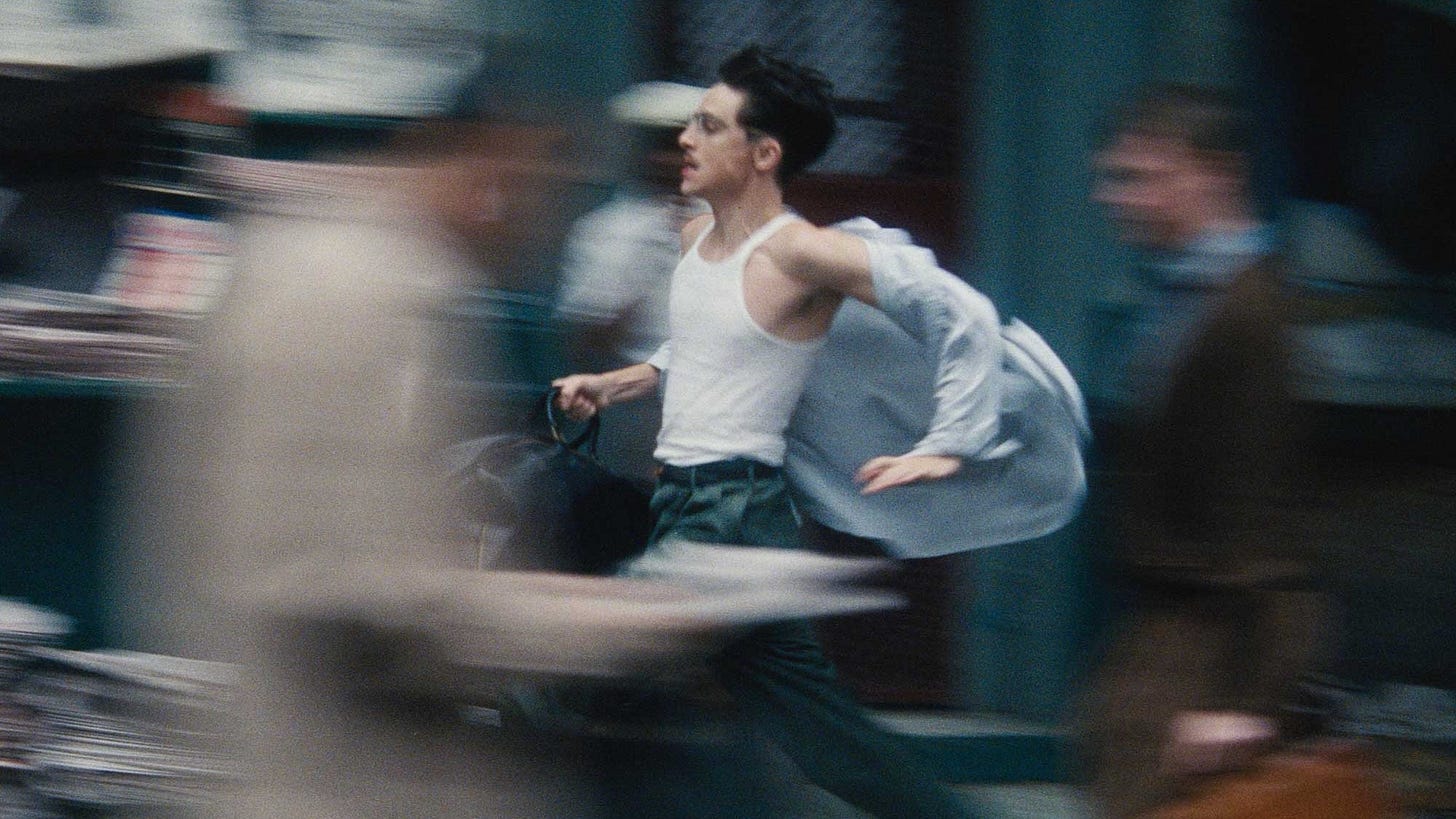

4. Marty Supreme

Directed by Josh Safdie

Here is a film that knocked me sideways from its opening moments – in which Alphaville’s “Forever Young” scores one of the boldest opening credits sequences I have ever seen – and never stopped continuing to surprise for another two-and-a-half hours. Marty Supreme is nominally about table tennis – inspired, though not actually ‘based on,’ the life of flamboyant American champ Marty Reisman – but actually spends more time depicting things like armed robbery, car crashes, gas station explosions, runaway dogs, surprisingly graphic violence, and charged moments of sexuality, both in private and in public. By the time one realizes this film about a cocky ping-pong boy is going to have an honest-to-God body count on par with John Carpenter’s original Halloween, your expectations will have been so thoroughly recalibrated that the film’s biggest surprise turns out to be the way it ends on one of the sweetest and most disarmingly human notes of any film this year.

Marty Supreme instantly joins the annals of great movies about awful characters whose worst traits the film just keeps upping the ante on, challenging the audience to keep following along, and challenging the actor to find whatever shreds of compelling humanity might keep us wanting more. This is the part Timothée Chalamet was born to play, the kind of showstopping acting challenge that the great American legends of the 70s or 80s – particularly Al Pacino or Robert DeNiro – cut their teeth on. Marty is endlessly manipulative, almost never truthful, cynically uses every single person who comes into his life, and is bursting at the seams with ridiculous unearned bravado – and yet Chalamet makes him utterly captivating, a great film character you cannot take your eyes off of, in part because of the various ways he subtly communicates how Marty himself doesn’t seem to believe any of this bullshit either.

And it’s in that space that Marty Supreme rises from perhaps the most purely entertaining film of the year to become one of the great movies about America itself. As we learn early in the film, for all his endless self-aggrandizing, Marty Mauser is merely a very good table tennis player; when he’s up against a truly generational talent, he cannot hold his own. Marty hustles endlessly in an attempt to prove – to himself as much as to anyone else – that he can fill the gap between ‘very good’ and ‘genuinely great’ with an overwhelming barrage of weapons-grade bluster and bottomless capacity for shamelessness. Viewed in 2025, it’s impossible not to connect that central question to the fundamental dynamic of the entire American experiment: is it ever actually possible to tell a lie so hard, so many times, that it gets you over the line from where you are to where you need to be? I’ve long thought that Phillip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff is one of the greatest movies ever made about this country, an expression of the American id in all its insane ambition and restlessness, made manifest through the early space program, all wrapped in an epic that is also about fame, media, and the construction of heroes and myths. Marty Supreme sort of feels like the dark inverse of that movie, a film about all the same ideas breathed through the imagined life of a single weirdo who can’t actually change the world, but still understands to his core how the kind of myth he wants to embody gets constructed. Marty Mauser probably isn’t the cinematic hero we need right now, but goddammit if he isn’t the one we deserve.

Marty Supreme is currently playing in theaters everywhere. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

3. Die My Love

Directed by Lynne Ramsay

Lynne Ramsay’s Die My Love is of the most viscerally stressful and deeply upsetting films I have ever seen. It is also frequently beautiful, at times wryly funny, and always aching with a palpable, compelling humanity. Based on the 2012 Argentinian novel by Ariana Harwicz, the film stars Jennifer Lawrence as a new mother struggling with postpartum depression – though saying it that matter-of-factly sounds overly pat for how Ramsay approaches her subject matter. This isn’t so much a film about postpartum depression as it is a film told of and through this state of mental distress. It has much less in common with anything moviegoers watched in commercial multiplexes this year than it does the experimental films of Stan Brakhage, as Die My Love feels like something of a stylistic or spiritual descendent to any film where Brakhage weaved his camera through a home, a yard, or the woods, and/or where he turned bodies into spectral dancers on screen. The great cinematographer Seamus McGarvey moves his camera in the same ways, capturing spaces in similarly ethereal, liminal fashion, and allowing light to bounce off his lens in similarly striking, ghostly patterns. And Ramsay directs and blocks her actors much more like interpretive dancers than traditional movie performances. It’s a little like Terrence Malick, but with less twirling; the ‘dances’ here are more visceral, less symbolic, and confrontationally vulnerable.

Die My Love is mostly a two-hander, between Robert Pattinson – great as always, playing brittle, shaky, and bruised in ways he is uniquely capable of illustrating – and Jennifer Lawrence, in an astonishing, career-defining performance. She acts here with her whole body, in total commitment to the strange, scarred dance steps Ramsay puts her through, embodying a woman who feels every inch of her body, yet cannot understand anything it comes into contact with. What Lawrence’s performance engenders is a sense of tactile isolation from the world: the body becoming an inescapable asylum, both refuge and prison. Roger Ebert once said movies are a machine for generating empathy, and while I don’t want to be too gender essentialist here, I struggle to imagine any cis man open to experiencing empathy walking away from this film without a deeper, richer sense of understanding and compassion for women, their bodies, and the expectations labored upon them.

This film is a harrowing watch, with nothing even approaching catharsis waiting for viewers at the end, let alone ‘answers.’ It’s uncompromising in how it depicts the subjective experience of feeling lost, adrift, angry, and confused, at war with one’s body, mind, and surroundings. In a time when it has become unmistakably clear how women’s bodies are (and have always been) central sites of contestation in our politics – and in a year where we re-installed an adjudicated rapist and proud misogynist into the White House – the challenging empathy Die My Love offers is more essential than ever. This is, after all, the fundamental function of art in its purest form: to take what is on the inside and express it on the exterior. To transmit something true and deeply felt to others who have not felt it, but desperately need to understand.

Die My Love is currently streaming on Mubi, and is available to buy and rent on digital retailers. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

2. One Battle After Another

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

While we can all debate what is the ‘best’ film of the year, or which ones are our personal favorites, it feels almost undeniable that Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest was the definitive film of 2025: the most widely and unanimously acclaimed, the most finger-on-the-pulse, the one that did the most to achieve a startling degree of film craft and arresting sense of entertainment within a story that felt vitally necessary for our present times. It is to 2025 what Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s Drive My Car was to 2021, or Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite was to 2019: a film likely to not just be remembered decades from now, but actively watched, discussed, and debated, a timeless work of art that also gives future generations vital insight into the time in which it was made.

In many ways, One Battle After Another plays like the ur-Paul Thomas Anderson film: it has the ensemble sprawl of his 90s Robert Altman riffs; the epic scope and register of There Will Be Blood or The Master; the paranoid stoner comedy of Inherent Vice; and a killer score from longtime collaborator Johnny Greenwood that has the same relentless intensity as Jon Biron’s work on Punch-Drunk Love, turning the entire film into an extended, non-stop panic attack. On the level of craft, the production is uniformly immaculate, with the crystal clear yet gorgeously textured VistaVision photography playing to outstanding effect on an IMAX screen. It is, like all of Anderson’s films, irreducible to a single genre, and could be argued as not just as one of the year’s foremost dramas, but also one of its best comedies and most thrilling action movies (there is a car chase near the end that is absolutely one of the best such action set pieces I’ve ever seen, in part because it is so ingeniously simple in its staging and presentation).

While Anderson’s films have always spoken to the present, even if obliquely, One Battle After Another is unmistakably about the America of 2025, highlighting the state-led torment of immigrants and the re-emergence of explicit white supremacist politics as animating forces of resistance, solidarity, and political violence. In a year where corporations bent to Donald Trump’s authoritarian impulses left and right, and blanched at anything that might upset the fascists in power, it is actually remarkable this film even came out, let alone played nationwide in IMAX venues at the end of the summer movie season. The film does not glorify or celebrate the Weather Underground-style domestic terrorism its characters engage in, but neither does it outright condemn violent resistance in a context of abusive state repression. It knows which kind of violence is worse, and it knows there’s a lot of beauty in the struggle too. In many of its most poignant moments, in fact, the film is a veritable ode to grassroots acts of solidarity, its story woven with countless little grace notes of people in a targeted underclass looking out for one another as the state sticks its boot in their faces. Benicio del Toro, in perhaps the great scene-stealing performance of 2025, spends the entirety of his screentime arranging escape routes for targeted immigrants and helping DiCaprio’s character reinvigorate his atrophied revolutionary muscles. After a year spent watching Trump send jackbooted thugs to invade American cities and abuse, kidnap, and disappear our friends and neighbors, neither the evils nor the responses One Battle After Another depicts are hypothetical, and the film very definitively picks a side.

This is a film about imperfect people resisting imperfectly, and coming out the other side together. The point isn’t being faultless or acting flawlessly, but pooling one’s strengths and imperfections into a community who can use what you’ve got and make up for what you don’t. It’s a film about the small, impossibly vital heroism of showing the fuck up, adding your weight to push that boulder up the hill, and trusting that others – in your time, in your children’s time, in their children’s time – will eventually get it all the way there. We do not live on through so many successive battles and hardships individually; we do it as a collective, and through our individual faults, we make each other better. Maybe that’s what hope actually looks like right now.

One Battle After Another is currently streaming on HBO Max, is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and will be available on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K UHD on January 20th. You can read my full review of the film at this link.

1. The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel

Created by Lindsay Ellis

Yes, I am naming a 142-minute YouTube video the No. 1 film of 2025. Please hold all questions to the end.

The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel, by the popular and influential video essayist (and sci-fi author) Lindsay Ellis, is not a ‘film’ by most commonly accepted definitions. It did not play in theaters, but was posted for free to YouTube (and Nebula, where Ellis exclusively releases most of her video work these days). You can watch it right here in the middle of this article, embedded on this page. It cannot be logged on Letterboxd, nor is it listed on IMDb. Ellis does not credit herself as a ‘director’ (in fact, the video contains no credits at all), and calls the work a ‘video’ at the outset.

But the ‘video essay’ as a form was not homegrown on YouTube in the 21st century. It comes down to us from canonical filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard (Histoire(s) du cinéma or Goodbye to Language), Chris Marker (A Grin Without a Cat or Sans Soleil), and Orson Welles (F For Fake), whose ‘essay films’ wrestled multimedia, news, politics, philosophy, and rhetoric together into works of powerful ideological synthesis. Many of the great 20th century essay films are frequently counted among the greatest movies of all time (all the films I just referenced received multiple votes in the 2022 Sight & Sound poll). Internet distribution and the proliferation of consumer video and editing tools have enabled the ‘essay film’ to enter a new period of history, with a wide array of impressive ‘video essay’ work regularly finding an audience on YouTube. And I would argue that Ellis – who is arguably the chief voice in the development and popularization of media-related video essays in the YouTube age – has, in The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel, not only created the current peak of the form as it exists on today’s internet, but connected us back to the essay film’s 20th-century antecedents in demonstrating how dense, rich, and provocative such works of videographic rhetoric and synthesis can be.

All of which is to say: I would argue such a work can indeed be counted as a ‘film’; and once I have made that argument, I feel very strongly that The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel stands in some way above everything else I watched this year.

The fundamental quality of all great essay films lies in their capacity for synthesis: how many ideas can one string together, through the interrogation of how many different modes of media and individual works, in service of one larger, unified idea? Ellis structures these 142 minutes like an accordion: It begins, narrowly, on the case of bad-faith accusations of antisemitism against popular children’s entertainer Rachel Accurso, whose advocacy for children in Gaza have made her the target of slander, invective, and propaganda from some of the world’s worst people (what Ellis calls “the ‘won’t someone think of the children (no not those children)’ brigade”). And then it expands, wider and wider, to tell multiple histories and trace their contestations into the present day: First as a survey of children’s entertainment in the United States over the last 60 years, from Sesame Street to Mr. Rogers to Blue’s Clues, in tandem with our evolving understanding of childhood development and education; then as a theological history of the Jewish diaspora and the development and spread of antisemitism; and finally as an exploration of genocide as both a persistent historical reality and a perpetually-contested legal and discursive formation. Along the way, Ellis discusses pedagogy and parenting, gets into some musical theory, probes faith and theology, and even makes room for her endearing, long-standing obsession with musical theater and the works of Andrew Lloyd Webber. And in the home stretch, she compresses the accordion inward, tying every one of these wide-ranging threads together into a single, totalizing narrative of the crisis of morality seizing global politics in the 21st century: the death of compassion and the targeted, sustained campaign against empathy.

The ‘unforgivable sin’ of the video’s title is Ms. Rachel’s insistence on leading with those two qualities, even and especially when that empathy guides her attention and advocacy across the world to children in a far-away warzone. Our politics has turned vice into virtue, with the dominant political movement in the United States built around the celebration of inflicting pain on the vulnerable and exacting retribution against those who would do otherwise. A large chunk of Ellis’ essay is about the genocide in Gaza and our country’s complicity in the violence, but it also touches on recent horrors of the second Trump administration like the kidnapping and extraordinary rendition of Kilmar Abrego Garcia and others; the creation of ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ in Florida; ICE’s widespread crimes and abuses on domestic soil; and the truly vile propaganda celebrating and foregrounding the gleeful cruelty of all of it. The ‘sin’ of Ms. Rachel is also the ‘sin’ of educational programs that foreground empathy in their pedagogy; of Ms. Rachel or Fred Rogers’ signature style of talking directly to children as equals and affirming the authenticity of their feelings; of considering the lives of children born to another race or religion as equally sacred to those of one’s own community. These are the ‘sins’ we are being taught to avoid, that our free speech is being suppressed to disincentivize. The vulgarity of our times can be measured in what our leaders consider moral, in the evils our fellow citizens are willing to embrace as ‘virtuous’ displays of their social or political identity. We live in profoundly vulgar times indeed.

The formal excellence of Ellis’ work lies in the edit, in the assembly of visual and auditory data woven together to fashion a grand narrative out of many small ones. There are several tour-de-force passages contained in these two-plus hours. Some are journalistic, like a section in which Ellis more persuasively and comprehensively demonstrates how deeply antisemitic and aligned with contemporary Naziism America’s current conservative regime is, in ways much of our mainstream media has willfully ignored. Others are more inquisitive and philosophical, as in the sequence where Ellis discusses the films Schindler’s List and Hotel Rwanda (and the real-life stories of Oskar Schindler and Paul Rusesabagina) as examples of the sheer impossibility of understanding historical atrocities through numbers, landing on related passages of the Q’uran and Talmud each expressing the idea that “whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.” And others still are based purely in editorial juxtaposition, as when Ellis plays the words of Mr. Rogers, from decades ago, next to images of children suffering in Gaza, imploring us to remember that the common humanity Fred Rogers called us to extends across time and borders and race and religion. I have watched The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel twice, and have been absolutely floored, both times, when its accordion structure starts to move inwards again, and Ellis powerfully and propulsively focuses our attention on the darkness of the present through the framework of Ms. Rachel and Mr. Rogers’ work, demonstrating not only the staggering depth and complexity behind the way they interacted with and advocated for children, but also the humbling simplicity of the moral task in front of us.

Here is the bottom line: 2025 fucking sucked. My country jumped leaps and bounds down the road to authoritarianism, and was responsible for so many truly unforgivable crimes that there were days my own empathy made it hard to get out of bed in the morning. I found myself sitting in the campus parking lot, trying to work up the will to go into work and teach classes on cinematography or animation, wondering if it was even moral to do so while my tax dollars went to fund a criminal administration terrorizing citizens and non-citizens alike on a daily basis. I still don’t have an answer to that question; at the end of her video, Ellis pointedly refuses the platitudes of easy answers or promise of a clear path forward. But by the time she reaches that point, she has already done more to help me make sense of this awful year and our deeply broken world than any other piece of media I engaged with in 2025. What we must do in times like these is ultimately unknowable on an individual level; but the first step comes in contextualizing and understanding, in diagnosing and giving shape to the problem – in comprehending and learning to sit with ‘the mad we feel,’ as Mr. Rogers would tell us. In 2025, I don’t think anyone else did it better than Ellis. And I don’t think there’s any piece of moving image media from the past year I can more powerfully recommend than this one.

The Unforgivable Sin of Ms. Rachel is streaming for free on YouTube, where it is also hosting an ongoing donation drive to the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund.

Read the book 200 Reviews by Jonathan R. Lack in Paperback or on Kindle

Subscribe to PURELY ACADEMIC, our monthly variety podcast about movies, video games, TV, and more

Like anime? Listen to the podcast I host with Sean Chapman, JAPANIMATION STATION, where we review all sorts of anime every week. Watch on YouTube or Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.