The Top 10 Films of 2023

In which we praise 29 different films from a great year of cinema

2023 was a remarkable year for the art of cinema, one of the densest and deepest collections of movies I’ve ever seen in a 12-month period. It was also a big year for my relationship with movies, as the year I got my groove back for writing film reviews. After several years focusing mainly on the podcast(s) and my academic pursuits, I started writing movie reviews regularly again this year – so regularly, in fact, that I wrote more reviews this year than I have in any year since at least 2014, and that’s not even counting all the new material I wrote for the book I published in October, 200 Reviews (shameless plug!).

I cannot explain what exactly re-ignited my passion for writing movie reviews; I was pretty burned out on the exercise by 2015, having done it regularly for over a decade and half my life at that point, and the muscles atrophied over time. For whatever reason – maybe because I discovered the joys of Letterboxd, maybe because I cut back my time on other social media, maybe because I kicked my Ph.D. dissertation writing into high gear this year and was simply in more of a writerly mood – I started building those muscles back up this year, re-launching JonathanLack.Com as The Weekly Stuff Wordcast here on Substack, and had a lot of fun doing it. Movie reviews are the relationship I don’t know how to quit.

It helps, of course, that 2023 really was a wonderful year at the movies (on the artistic side, at least – on the business side, it is of course a much messier story, but that’s a conversation for another day). I wanted to write about all of these films, because they gave me so much to think about, to praise, to muse upon. Cutting things down to the main Top 10 was brutally difficult, and ranking everything was even more painful; the top 6 in particular is quite possibly the densest pile-up of capital-G Great movies I’ve ever had bundled together on one of these year-end lists. In addition to the main Top 10, I also have an additional 10 ‘honorable mentions,’ bringing us to an overall Top 20, plus another batch of leftovers also worth celebrating. #20-11 have paragraph-length capsule statements, #10-#3 get two paragraphs apiece (mostly, one of them involves a 5-way tie), and I went a little longer on the best film of the year. But if you want to read more from me about any of these films, links are provided throughout to my full written reviews (and, where applicable, podcasts episodes about the films from The Weekly Stuff).

The ground rules are, as always, simple: A “2023 movie” means a film that made its commercial debut in the United States in 2023, theatrically or on streaming. Some of these films are listed under 2022 on sources like Letterboxd or IMDB because of festival or overseas debuts, but they are 2023 movies as available here in America. So without further ado, let’s get started!

(And if you love my voice or just hate reading, you can click on the YouTube video at the top of this page to listen to the audio version of this article, with me reading all this text!)

Part I: Leftovers

Here are five films that finished outside the Top 20 I want to briefly commemorate, in no particular order: Pedro Almodovar’s Strange Way of Life was short but sweet, with two of the year’s best performances from Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal, and an unforgettable score from Alberto Iglesias; Kenneth Branagh made his best film in decades with A Haunting in Venice, a whodunnit dripping with atmosphere, loaded with great performances, and shot through with both a poignant sense of sadness and a pervasive zeal for cinematic creation; Chinese mega-hit The Wandering Earth II was easily the year’s craziest blockbuster, director Frant Gwo working with resources most filmmakers could never dream of and making full use of all of them in a globe-hopping, interstellar, ridiculously bombastic adventure with a cast of thousands that is scientifically dubious but deeply thrilling and entertaining (it’s also a movie about Andy Lau conquering death itself in a trippy transhumanist narrative, in case you weren’t already sold); Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour was perhaps the grandest spectacle to grace theater screens this year, but while it’s a very accomplished concert documentary, I would say it’s a greater achievement of stagecraft and live performance than it is of filmmaking, which is my justification for leaving it off the main 20; and finally, the year’s hardest cut for me was Barbie,which saw Greta Gerwig making the jump to blockbuster filmmaking with her voice completely intact, crafting a movie so funny, confident, and smart that what sounded on paper like a terrible idea instead became the defining cinematic cultural event of 2023.

Part II: Honorable Mentions (#20 - #11)

20. It is not my place to judge the ‘authenticity’ of Past Lives (US, Dir. Celine Song), a film about a married woman who reunites with a man she loved as a boy before emigrating to the US from South Korea, but it sure feels achingly authentic to me – and it’s undeniably one of the most deeply felt, passionately told films of the year. I love how slowly and methodically the film develops character, mood, and atmosphere, how willing it is to sit with uncomfortable emotions, and acknowledge how resolutely life doesn’t bend to clean narrative scripts, without ever making anyone out to be a villain or bad actor. Past Lives is about good people trying to process complex, messy feelings, and it feels like something of an emotional exorcism for everyone making it. And all of it is stunningly beautiful, with cinematography that calls attention to itself insomuch as the compositions are always telling a story, sometimes from unexpected vantage points.

19. Rewind & Play (France/Germany, Dir. Alain Gomis) is a remarkable film about the agony and ecstasy of music and media, of documentary and truth, of 'performance' as a multifaceted and fraught idea. Crafted from the raw footage of a documentary on Thelonious Monk made for French television in 1969, Jazz Portrait,Gomis’ film lays bare the uncomfortable reality of the role Monk is asked to play for the cameras, as stupid and shallow questions are answered with what French interviewer Henri Renaud deems unacceptable simplicity, and the one deep, incisive response he gets out of Monk is rejected as derogatory. “It's not nice," Renaud explains to an exasperated Monk, who realizes he isn't here to speak his truth. He can, at least, play it – and the other half of the film, spent watching Monk alone at the piano playing transcendently, is astonishing and transfixing. But the juxtaposition Gomis creates here – or uncovers, as it may be more accurate to say – imbues that performance with more than just the appreciation of musical genius at work. There's a frustration and a fury to it too, a sense of Monk articulating himself through the contact between his fingers and the keys in ways he couldn't, or simply wasn't allowed to, with his words. Read my full review here.

18. Suzume (Japan, Dir. Makoto Shinkai) is a road movie in two parts, the teenage-bonding-cum-disaster-flick shape of the first half giving way to the more intimate, emotionally fraught determination of the second, with diverse locations across Japan constantly giving the film an ever-evolving sense of grounded locality. Set pieces occur in the ruins of both natural disasters and economic downturn, with the high-point of the film’s spectacle coming in a struggle at an abandoned amusement park atop a ferris wheel. But no matter where the characters are, it feels like they’re somewhere specific, and the theme of empathizing with the dead who haunt these spaces is some of the most affecting work in Shinkai’s filmography. The film climaxes with its protagonists screaming in defense of their own existence into the void of death and destruction, a moment that mirrors ways in which both Your Name and Weathering With You resolved their own thematic tensions, but with a full-throatedness, literally and figuratively, I found startling, a way in which metaphor and fantasy are briefly stripped away to let the characters say what needs saying, directly, to the land and to the world itself. As a production, Suzume is an impossibly lush widescreen triumph featuring set piece after set piece rife with astonishing levels of kineticism; the depiction of movement here, from people to cars to an animate chair, is jaw-dropping. And even by Shinkai’s always-high standards, the character animation, color work, and hyper-detailed backgrounds are a cut above. The space of a movie theater rarely feels as exhilaratingly transformed as it does here. Read my full review here.

17. On paper, Blackberry (Canada, Dir. Matt Johnson) sounds like part of this weird new genre of “product biopics” (priopics?) that has cropped up this year, alongside Air, Tetris, and Flamin’ Hot. In actuality, it’s a much more compelling and complicated film than those, not at all the celebratory or feel-good story of ingenuity winning the day, but a dark and provocative parable about the cutthroat, soul-crushing, ethics-demolishing incentives of our current tech-driven growth-at-all-costs late capitalist hellscape, using the real-life rise and fall of the BlackBerry cell phone brand to tell a story that’s achingly familiar across multiple industries: the Faustian bargain and gradual dismemberment of the soul that follows from turning a personal passion project into an international, publicly-traded mega-corporation. The film is driven by two extraordinary performances from Jay Baruchel and Glenn Howerton, the latter only a few degrees off from his many years of work as Dennis on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, a being of raw but flaccid rage who is alternately terrifying and darkly funny. Riveting and entertaining, but also confrontational and thought provoking, Blackberry is a finger-on-the-pulse reckoning with a certain kind of story that’s become disturbingly endemic to Western economies and culture, immediately taking a place among the best films about this era of tech and communication. Read my full review here.

16. Anatomy of a Fall (France, Dir. Justine Triet) is written, performed, and photographed with astonishing nuance and precision, taking the shape of what could be an intense legal thriller – a man dies falling from his house, with only his wife, Sandra, around when it happens, leading to her being put on trial for his murder – and instead making something slow and simmering, a film about studying faces and sitting with emotions. Rather than the simplistic ‘whodunnit’ lesser films might have offered, Triet delivers a dissection of a marriage and a family unit, and of all the difficult nuances of human behavior and relationships which create the unstable foundations society wants to project easily digestible cookie-cutter perfection upon. The world looks at Sandra and at the case surrounding her and wants to see something neat and binary, a one-word answer to a person and a marriage and a family of real everyday complexity. That is impossible, but the destructive ends of that impulse are very, very real. Read my full review here.

15. Shin Ultraman (Japan, Dir. Shinji Higuchi) would almost certainly be even higher on this list if I had a stronger pre-existing relationship with the world of Ultraman, but even as a relative newbie, this film is an incredible treat. Narratively bold in how in it bends episodic televisual storytelling into a rapid-fire cinematic stream-of-consciousness, the stakes and the state of the world constantly shifting beneath our feet from moment to moment; and formally audacious in its absurd barrage of camera angles, the film’s eight credited cinematographers placing versatile digital cameras in every position they can possibly think of, from desks and chairs and computers to within a bag of potato chips; Shin Ultraman is one of the most exciting, infectiously giddy superhero movies ever made, a carefully-calibrated camp masterpiece drunk on the wondrous possibilities of Saturday morning heroics. Listen to our full review on The Weekly Stuff Podcast.

14. A profane and poignant fairy tale for adults, Poor Things (Ireland/UK/US, Dir. Yorgos Lanthimos) is gloriously demented. The film is equal parts clever and childish in its sense of humor, frequently grotesque and graphic, brazenly sexual (though rarely erotic) throughout, and astonishingly beautiful in every moment. In its cinematography and design, yes, but also in the film’s enduring, disarming sweetness. Lanthimos has crafted a big-hearted movie about the strangeness of being alive, one that takes the Frankenstein-cum-Pinocchio idea of a person who is fully grown physically but tabula rasa mentally – portrayed brilliantly by Emma Stone in the best performance of her career to date – to explore what is ecstatic, hollow, violent, uncanny, and wonderful about life, and ultimately come to the conclusion that our messy, transient existence is, in sum, quite interesting, and therefore quite worthwhile. Read my full review here.

13. Bottoms (US, Dir. Emma Seligman) is raucous, unhinged, and brilliant – the best time I had with a crowded opening-night audience all year. What I love so much about what Seligman and star/co-writer Rachel Sennott have done here is that they’ve not only taken the shape of a raunchy teen sex comedy (think Revenge of the Nerds or American Pie) and made it gay, but they’ve made it so much weirder and wilder, so much more extreme and surreal than basically any of the movies they’re pulling from – while also nailing the character and emotional beats better than nearly any precursor. Rachel Sennott is a complete, utter movie star here, while Ayo Edebiri is both the movie’s grounded center and a fount of wackiness in her own right. Oh, and that score – by Charlie XCX and Leo Birenberg – is one for the history books, a crazy propulsive techno/house soundscape that gives the movie such a unique sound and energy. I spent months after this came out listening to nothing but Charli XCX for good reason. Bottoms is just an utter mic drop of a movie, wildly confident from start to finish, riotously funny throughout, always surprising and unexpected. I loved every minute.

12. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (United States, Dir. Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, Justin K. Thompson) is only half a movie – and held back slightly for the purposes of list-making since we have yet to see the full story unfold – but it still makes damn near every other superhero film look like Morbius. Wildly and singularly bold in style, whole swaths of Across the Spider-Verse push towards pure abstraction, the boundaries of its aesthetics, visual logic, spatial relations, and color palette all determined by emotion, theme, and character, or just by the adventurous whims of the artist in the moment, creating a kaleidoscopic visual symphony that is almost unprecedented for massive populist cinema like this. That the film not only finds space for a damn good story amidst all this visual virtuosity, but like the first film uses its dimension-hopping aesthetic anarchy as an essential springboard for so much of what this story has to say, feels like a borderline cruel dunk on everybody else working in the superhero space. Across the Spider-Verse is at its core a coming-of-age film, but what makes it so special is how it takes the metaphor and blows it wide open, weaponizes our culture’s current interest in multiverse stories and evergreen obsession with Spider-Man mythos into a playing field where the emotional intensity and messiness of its ideas can be made manifest. Nothing in this movie looks real, and every inch of it feels true – that’s art, in a nutshell. Read my full review here, and listen to our in-depth discussion on The Weekly Stuff Podcast.

11. Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (US, Dir. Christopher McQuarrie) is nothing short of a magic trick. Here is a Mission: Impossible movie that revolves around chasing not just a MacGuffin, but a literal key – what it unlocks we do not learn until near the end – and yet nothing about the film or the motivations of its characters ever feels thin. Seven films and 27 years deep, Dead Reckoning manages to deliver the smartest and most soulful entry yet, fully satisfying on its own terms despite the “Part One” moniker. The film is filled with all the deliriously creative action one has come to expect from McQuarrie’s direction, but also imbued with a degree of tension, atmosphere, and weight unlike anything we’ve seen from the franchise before; alongside the best character-driven storytelling in the series’ history, there’s a little bit of existential sadness here, a sense of inevitable finality, that makes everything just that much more riveting. The amazing stunts, ludicrously creative set-pieces, propulsive score by Lorne Balfe, ever-committed work from Tom Cruise, and a joyous star turn from Hayley Atwell all help – this really might be the best Mission so far. ‘Magic’ is the only word for it. Read my full review here, and listen to our in-depth discussion on The Weekly Stuff Podcast.

Part III: The Top 10 Films of 2023

10. The Killer

United States, Directed by David Fincher

As a longtime David Fincher agnostic, The Killer is easily the most I’ve ever enjoyed his work, in no small part because the film feels like it's in conversation with what has previously frustrated me about the director. Much has been made of the ways the film feels 'personal’ to the filmmaker, given how the Michael Fassbender character's obsessive methods mirror Fincher's own directorial style. And certainly, as an action procedural – a movie dedicated to watching a violent professional go through every step of the process – The Killer is astonishingly immaculate, a well-worn story told with such overwhelming attention to detail, such exceptional craftsmanship, that it could really only come from a director with as obsessively precise and casually cool a sense of style as the archetypal killer himself.

But if The Killer is in any sense autobiographical, it feels lacerating, an auto-critique that brutally tears down the mythos around this kind of archetype before building the character back up as an empty signifier, blank and knowingly hollow. The procedural undercuts itself at every turn as the protagonist continually runs into the limits of his own inflated ego, the whole film shot through with this sly, self-deprecating humor. In the end, The Killer is compelled to systematically, surgically reveal why this character – and why this entire character type – is full of shit; if Fassbender's character has come to find any inner peace at the film's end, it comes through accepting how he is, in truth, unexceptional. So while the central assassin revenge drama is fun, the true tension of the entire film lies in just how exceptionally made it is, Fincher tearing down the myth of the obsessive loner genius with one hand even as he proves his own exceptional talent with the other. There are no easy answers to that tension, no way to readily resolve the contradictions the film creates, but that is part of why it lingers, and why it stands tall as one of 2023’s best.

The Killer is currently streaming on Netflix.

Read my full review of THE KILLER here.

9. Ferrari

United States, Directed by Michael Mann

Michael Mann has always made movies about dangerously obsessed men. Such focus gives him the necessary clarity of vision when it comes to tackling a project like Ferrari, which is a doubly dangerous undertaking as both a biopic (the most creatively bankrupt of all Hollywood genres) and a passion project (Mann has been trying to make the film for a quarter of a century). Mann is interested in Enzo Ferrari because he recognizes the deadly obsession beneath the man’s placid exterior as one of his subjects, different in occupation and personality than the cops and criminals of Thief, Heat, and Miami Vice, but not different in kind; and he is interested in Enzo Ferrari at the very specific juncture in the man’s life this film queues in on – a few weeks in the summer of 1957, leading up to that year’s Mille Miglia – because it crystallizes what makes the subject interesting into an intense pressure cooker of passion and pathos. Mann does not come to Ferrari because of the man’s notoriety and then search for a story to tell, as do the vast majority of biopics; he first and foremost has a theme to explore, and he comes to Ferrari because the man’s story, which just so happens to be true, opens an extremely compelling perspective on that theme.

The film’s smart and riveting character drama is centered in absolutely towering turns from Adam Driver and Penélope Cruz, and assembled with exquisite craftsmanship. Cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt and composer Daniel Pemberton contributed to films each I’ve included here – Messerschmidt for shooting The Killer, Pemberton for scoring Across the Spider-Verse – and they’re doing similarly excellent, if very different, work here. Stylistically, Mann is playing things straighter in this film than he has in at least two decades, but he is also playing for keeps. His Ferrari does not exist to celebrate or extol or give viewers a cradle-to-the-grave history lesson on its subject; the film does not care if you like him, and it has no designs on deifying him. It finds him fascinating, and desires to understand him, and given the sweep of Mann’s career, it inevitably feels personal, as though understanding something about the obsessions of Enzo Ferrari will illuminate something deeper about the obsessions of Michael Mann.

Ferrari is now playing in theaters.

Read my full review of FERRARI here.

8. Godzilla Minus One

Japan, Directed by Takashi Yamazaki

I was fully expecting an incredible spectacle out of Godzilla Minus One, given the hype around the film and the pedigree of director Takashi Yamazaki, one of the 21st century’s greatest VFX masters. And the film does indeed deliver 110% on that front. It is such a terrifying and fully realized vision of Godzilla and its postwar period setting that it puts the vast majority of Hollywood blockbusters from the last 15 years to utter shame, even before you consider this movie cost a minuscule fraction of the cost of your average Marvel movie. As a disaster movie, monster movie, and big theatrical blockbuster, Godzilla Minus One is immaculate, proof that Hollywood no longer has any kind of real dominance in this space. And as good as the effects and direction are, the score, by Naoki Satō, deserves just as much credit – with some choice deployments of classic Akira Ifukube tracks too.

What really surprised me about Minus One, though, is that the spectacle is far from its greatest achievement. This is, far and away, the most I have ever cared about and been emotionally invested in the human drama within a Godzilla film. I am not one of those people who just automatically resents all the parts with the humans in these movies – the original 1954 film, 2016’s Shin Godzilla, and even the unfairly maligned All Monsters Attack, with its delightful child-eye view on the monsters, all have great human stories to tell. But Minus One takes it to another level with its incredibly thoughtful, passionate, and thematically precise exploration of characters learning how to live again in the wake of the Pacific War, its small-scale human drama serving as a synecdoche for a nation choosing life after years of valuing death and sacrifice. The film embraces melodrama in the best and fullest sense of the word. The performances are uniformly remarkable, and ther e are moments of intense emotionality that I found as jaw-dropping as anything with Godzilla himself. It all comes together in a third act that so beautifully marries theme, character, history, and spectacle that I had trouble staying still in my seat, wanting to leap up and cheer on our heroes not only towards defeating the monster, but towards being their best selves. This is a big, terrifying, awe-inspiring, and beautiful movie, a vision of Godzilla that not only feels bold and culturally-specific, but personal, in a way you don’t expect walking into a Kaiju movie. It is wholly remarkable.

Godzilla Minus One is now playing in select theaters.

Listen to Sean Chapman and I review GODZILLA MINUS ONE on The Weekly Stuff Podcast.

7. John Wick: Chapter 4

United States, Directed by Chad Stahelski

Calling John Wick: Chapter 4 one of the greatest action films in the history of the cinema feels like underselling it, somehow. The film’s myriad accomplishments are bigger than that. What Chad Stahelski, Keanu Reeves, cinematographer Dan Laustsen, production designer Kevin Kavanaugh, and every other artist involved here have achieved – what they have been building towards for nearly a decade across these four films – is a tour-de-force of kineticism on par with the silent film greats that inspired Germaine Dulac to declare ‘movement’ the essence of cinema, the definition of cinégraphie, or Jean Epstein to declare animism the soul of cinema. John Wick 4 is a deliriously thrilling action movie, yes, but it is moreover a testament to light and color and shapes in constant motion, in a breathtakingly synchronized dance, the possibilities of the art form itself made manifest in the incredible images captured and the relentless momentum with which they are strung together, pushing the viewer into a powerful out-of-body experience.

The mastery of cinematic craft on display in Chapter 4 is truly overwhelming, is truly humbling to watch unfold as a lover of the art form. Every set is a stunner. Every action beat takes place against a backdrop so bespoke and colorful and precisely lit that it barely feels possible. Every shot is so strikingly well-composed that cuts kept taking my breath away, as each subsequent image stuns anew. The sound design is equally extraordinary, and Tyler Bates and Joel J. Richard have composed a killer neo-Western-techno score that feels like it’s blasting out from the walls of the mise-en-scene. The film is, in short, an absolute marvel of a production. It is not just style for style’s sake, not just action for action’s sake, but art, goddammit – big, beautiful, ambitious, audacious, thrilling art. Art that just so happens to involve shooting a whole lot of people in the head – but that also invites the viewer to participate, to lean forward in their seat, and gasp, and laugh, and feel their blood pumping harder and faster in their veins. The affective qualities of the cinema have rarely been felt so strongly as they are here.

John Wick: Chapter 4 is currently available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and is also available on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K UHD.

Read my full review of JOHN WICK: CHAPTER 4 here, and listen to Sean Chapman and I discuss the film on The Weekly Stuff Podcast here.

6. Asteroid City / The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar / The Swan / The Ratcatcher / Poison

United States, Directed by Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson directed five films in 2023: one 105-minute feature released to theaters, Asteroid City, and four shorts released to Netflix based on the works of Roald Dahl: The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, 39 minutes, and The Swan, The Ratcatcher, and Poison, each 17. All collectively push his signature style farther than it has ever gone, and all evince a simultaneous love for the act of telling stories – a giddy, inventive, infectious love – and a deep, passionate curiosity about why and how we tell stories in the first place. They are all critical texts reflexively engaged with the nature of storytelling, filmmaking, and performance – virtually every actor, in all five films, is playing two or more parts in each – and beautiful acts of praxis in their own right, at turns delightful, horrifying, thought-provoking, and moving. If the Roald Dahl shorts had been released as an anthology feature to theaters instead of being tossed into the bowels of Netflix where few seem to have even realized they exist, I suspect many more critics would be identifying 2023 as one of the single most important years of Wes Anderson’s storied career, a year where his long-standing fixations on artifice and framing devices and stories-within-stories achieved something of a kaleidoscopic apotheosis.

Asteroid City is presented as a ‘Golden Age’ (50s or 60s) TV program documenting the creation of a play, the eponymous “Asteroid City,” with the play itself being performed in the main body of the film, in color and in widescreen, with black-and-white scenes framed in the ‘Academy Ratio’ exploring the creative process. The action of the film isn’t so much what’s going on in ‘Asteroid City’ – the town, the play, or the movie – but what’s going on in the heads of these people who are writing, directing, and starring in it. Why tell a story like this – or tell a story at all – and what do we do when the art we make or participate in inevitably shines a light back upon us, as it always does? The film does, indeed, involve first contact with a quirky stop-motion alien, but instead of the alien’s arrival immediately and dramatically changing everything, it pointedly changes nothing. A person grieving their dead wife or mother who meets an alien one day is still going to be in the process of grieving when they wake up the next morning; and they will still know nothing about the existential mysteries prompted by her death. The ultimate challenge of life may not be to find the answers to all the great questions that weigh us down on a daily basis, but to instead find comfort in the not knowing. And while we are all unlikely to meet an actual alien to prompt such introspection, Anderson suggests through the film’s nesting doll structure that art itself is the encounter that makes us appreciate the unknowability of those quotidian mysteries, and that in the making and dissemination of art, we can come to find that comfort with the cosmic mysteries of life.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, the banner title in the Roald Dahl anthology, is Anderson’s version of Robert Bresson’s experiment in Diary of a Country Priest, where the filmmaker is not so much adapting the book as filming its text directly. Anderson goes even further than Bresson did, or than he himself has gone in previous reflexive engagements with the artifice of filmmaking, by dispensing with the idea of a closed diegesis at all, having the actors speak directly to the audience at all times and constructing every set as a one-sided proscenium a la the silent shorts of Georges Méliès from over 120 years ago. There is no fourth wall to break. The film’s visual, spatial, and temporal logic is dictated by the form of the literary writing, which in turn highlights the difference in form between novel and cinema. We are being told the story rather than watching it unfold. Time moves like it does in a book; when the narrator says 16 minutes have passed, suddenly they have. When the narrator tells us we are in a new location, the setting opens up behind us to show that scenery, without a cut. Anderson’s Henry Sugar is nothing less than a bold and radical attempt to visualize the workings of our inner eye when we read a story – or better yet, when one is read to us. “They forget that there are other ways of sending images to the brain,” says Ben Kingsley’s character, who can see without opening his eyes. It is the thesis statement of the film.

The other three shorts – The Swan, The Ratcatcher, and Poison – follow much of this stylistic logic while adding peculiar flairs of their own. The Swan is particularly confrontational in form, with Rupert Friend staring us dead in the eyes and reading this bleak, violent story in an unceasing rhythm, doing every voice himself, the space of the narrative a maze of interlocking soundstages from which there is seemingly no escape. The Ratcatcher is all about playacting, with minimal props and each actor jumping freely between characters; Friend is both an onlooker and the rat, while Ralph Fiennes plays the eponymous Ratcatcher, and Roald Dahl in the framing device, and the voice of a stop-motion rat as it embodies the character of the Ratcatcher (it’s complicated). The grisly climax, meanwhile, is depicted purely through pantomime. Poison is a tense but blisteringly funny tragicomedy of anticipated body horror, which reveals itself in its closing moments to actually be a piercing, bone-chilling parable about racism and class. The three shorts all dive into the darker, stranger, more grotesque and pessimistic side of Dahl’s writing, a side that has never really been committed to film in any extended fashion before. In this way, we might also call these shorts Wes Anderson’s first horror films – and as funny as the SNL skit The Midnight Coterie of Sinister Intruders is, these shorts reveal that Anderson’s vision of horror is quite different than the pastiche a parody could extrapolate from his earlier work. As always, Anderson is a far richer, deeper, and more surprising artist than those who mock or dismiss him understand.

Asteroid City is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and is also available on DVD and Blu-ray. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, The Swan, The Ratcatcher, and Poison are all streaming on Netflix.

Read my full review of ASTEROID CITY here.

5. Showing Up

United States, Directed by Kelly Reichardt

Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up is at once both a very small and an impossibly big film. Small because it is so intensely personal and low-to-the-ground, a relatively uneventful story about a few days in the life of a frustrated artist as she prepares for a show, where the stakes mainly amount to how much discomfort she feels with her life and how much discomfort we, the audience, are made to feel in turn. And yet it is also impossibly big because, in classic Reichardt fashion, this small slice of life is illustrated in such endlessly rich detail that it gradually takes on all the fraught, complex immediacy of real life, and comes to ask so many fundamental, unanswerable questions about the maddening grind of daily existence.

Michelle Williams is the star here, and while she’s always great, she is at her best working with Reichardt, who always gives her the space to perform quietly and subtly and with ample time to develop the emotions and physicality and voice of the character. The whole movie is so deeply lived-in and uncomfortably real, no part of it more so than Williams’ performance. Hong Chau is her equal, playing Williams’ artistically gifted landlady and nemesis, who gets her to take care of an injured pigeon, created with a truly spectacular animatronic that might be the year’s best special effect. But Williams’ most significant co-star might be the production design itself, credited to Anthony Gasparro, through which every space, every building, every color, and every costume choice tells a story. Showing Up is gloriously and rewardingly slow, beautifully detailed, and quietly but extremely funny, building to its surprising punchlines with clockwork precision. It is another high watermark in the Reichardt/Williams collaborative filmography, one of the richest director/actor pairings of my lifetime.

Showing Up is currently streaming on Paramount+ with Showtime, can be bought and rented on digital retailers, and is also available on Blu-ray and 4K UHD from A24.

Read my full review of SHOWING UP here.

4. Walk Up

South Korea, Directed by Hong Sangsoo

Hong Sangsoo’s latest is one of the most quietly devastating films I’ve ever seen: A movie that uses Hong’s singular long-take style and a simple but rigorously ordered structure – 4 major sequences separated by 3 ellipsis, each signaled by a recurring piece of music – to paint a vivid picture of a man in purgatory. A figurative purgatory, at least – a prison of behavioral patterns he cannot break out of and personal failings he cannot overcome – but also possibly a literal purgatory, as this is a film about a man who enters a building he is never able to leave within the bounds of the film, and whose retrenchment into this space is signified by a damning möbius strip ending that cuts off all possibilities of escape.

Hong stalwart Kwon Haehyo is extraordinary here as our prickly lead character, Byungsoo, a popular filmmaker caught in a rut and perpetually on the outs with those important in his life. He comes to a building owned by an old, estranged friend (or possibly ex-lover), Ms. Kim, along with his estranged daughter, to see if Ms. Kim can give her advice on a career in interior design. Years pass, and with each ellipsis, Byungsoo is stranded even more profoundly in this building and in his relationships with the women he encounters there. Each scene revolves around food and drink, and each follows a similar pace and flow, save for one arresting long take where Byungsoo retreats to his bed and imagines a mundane conversation with his girlfriend – a conversation he is, in reality, too petty and prickly and broken, in some deep-seated way, to actually engage in. With Kwon’s filmmaker protagonist serving as another potential Hong self-insert, the film feels deeply lacerating, a series of brutally honest and uncomfortable self-reflections that are left perpetually complicated, never resolving in absolution or revelation. There may be a way out of this building – the literal ‘walk up’ of the title or the figurative structure of melancholic isolation Byungsoo is enmeshed in – but if that exit exists, we don’t see it here. The film loops back on itself in its final moments in such a way as to make escape impossible. Byungsoo is left to haunt this space, and we are left haunted by the encounter.

Walk Up is available to buy and rent on Apple TV, and is also available on DVD and Blu-ray from Cinema Guild.

Read my full review of WALK UP here.

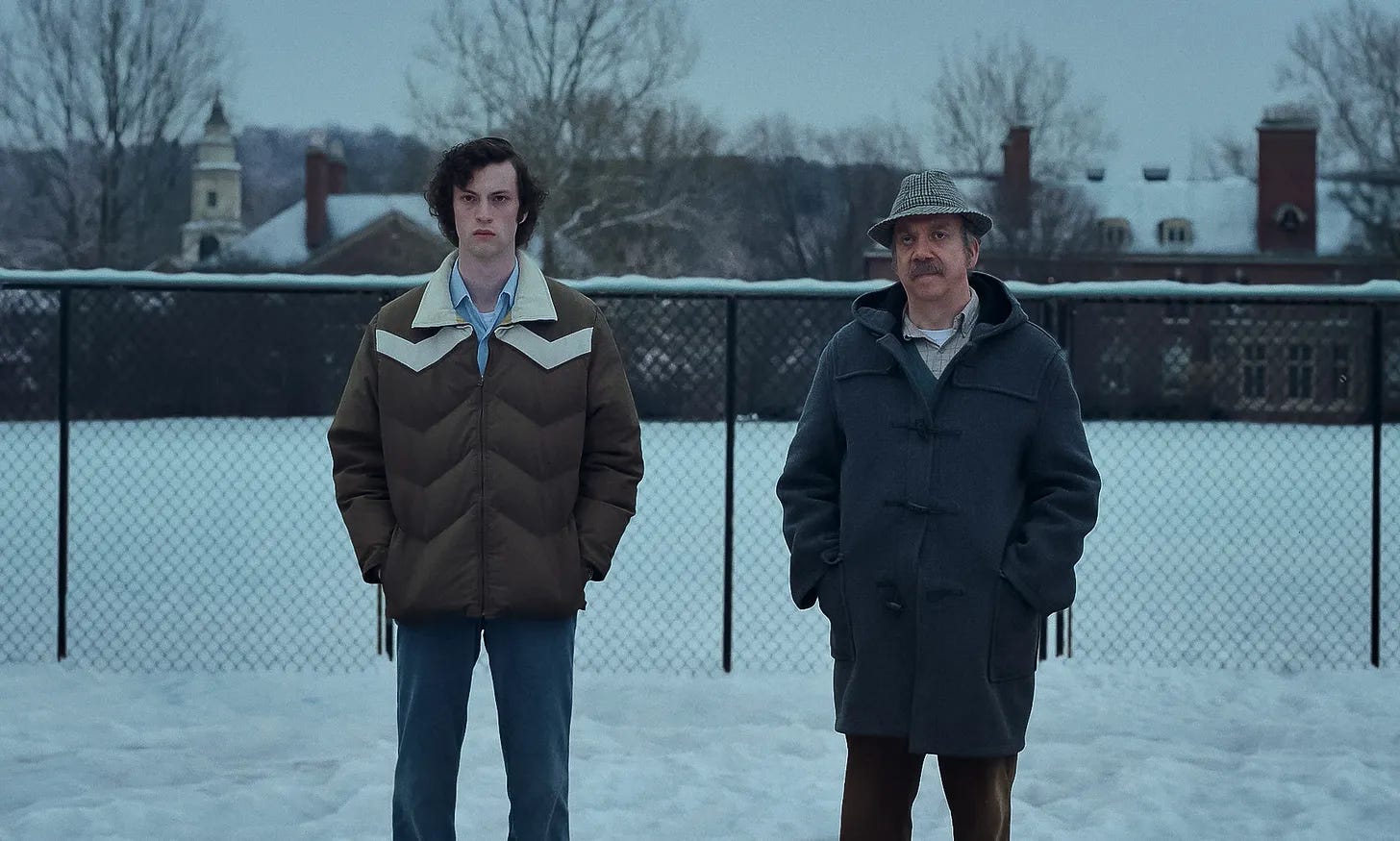

3. The Holdovers

United States, Directed by Alexander Payne

I love this movie like it’s a person.

I love it from the most basic layer of shape and texture – from its pitch-perfect 1970s celluloid aesthetic to the production design that is absolutely miraculous in its unassuming verisimilitude – up through the story and the characters, who by the film’s end feel like old friends the viewer has known for ages. The broad strokes of the narrative are simple and archetypal – a cranky Professor is charged with looking after a promising but behaviorally delinquent student over the Christmas break, both warming up and learning about themselves and each other as the days go by – but The Holdovers is singular. In its boundless love for its characters, and the pervasive empathy used to illustrate their world; in its engagement with the prickly realities of class, and the indignities many of us are wrongly taught to view as invisible; in the ways it understands people as unique amalgams of myriad contradictions, flaws, and virtues, and thus renders even the most fleeting of characters fully three dimensional and human; in its humor and its wordplay and its sharp, incisive wit; in its absolutely remarkable performances by Paul Giamatti, Dominic Sessa, and Da’Vine Joy Randolph; in its gentleness and its open heart, there are very few movies like The Holdovers.

This is the kind of movie where I spent the entire running time either laughing – this is a tremendously funny film – or finding myself on the verge of tears. Not because anything sad or even particularly emotional is going on in every scene, necessarily, but because every minute of it feels so real, so human. I see so much of myself and my life and the lives of people I’ve known in the film’s images and performances and dialogue. I found so much love and empathy and understanding for people and for parts of myself that have felt misunderstood or unloved. By the time the end credits rolled, I understood myself a little bit better than I did when the opening credits started. This is what great art is capable of, and watching The Holdovers feels like discovering that truth again anew.

The Holdovers is currently playing in select theaters, is available to buy and rent on digital retailers, and will be released on DVD and Blu-ray on January 2nd.

Read my full review of THE HOLDOVERS here.

2. May December

United States, Directed by Todd Haynes

Few, if any, films in 2023 dealt with pricklier subject matter than May December – the true story of Mary Kay Letourneau with the serial numbers filed off, of an adult woman who raped a middle-schooler and then married him after her stint in prison – but with Todd Haynes in the director’s chair, we are in the absolute most capable, sensitive, and intelligent of hands. May December may be the most ambitious tonal tightrope Haynes has attempted to walk since his debut film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story – a movie so dangerous to its surviving subjects that it can only be viewed as a multi-generational bootleg – and like that film, this one blends complete straight-faced sincerity and immense vulnerability with high, winking camp, its heart on its sleeve and its tongue planted firmly in its cheek.

May December is in subject matter an intimate film, but it is a gigantic work of art. The film is at times harrowing, at times hilarious, at times deeply uncomfortable and cringe-inducing, at times revelatory in its unbridled emotional honesty. Half the dialogue consists of double entendre, some of it subtle, some of it brilliantly sophomoric, often both at the same time. There are so many layers to what Haynes and his collaborators – including Julianne Moore weaponizing camp like a switchblade, a career-best Natalie Portman, and a revelatory turn from newcomer Charles Melton – are doing here, so many themes above and beyond just the central dilemma of grappling with a relationship built on an inexcusable crime. The film is also about performance, and image, and duality, and duplicity, and sexuality, and so much more. It is a movie positively rife with visual symbolism, much of it intentionally obvious, all of it still so complex. There are very few directors who work like this, who revel so unabashedly in contradictions, who use tone to destabilize and challenge their audience with such surgical precision; fewer still are capable of pulling it off. Haynes is singular, and this film is a masterpiece.

May December is currently streaming on Netflix.

Read my full review of MAY DECEMBER here.

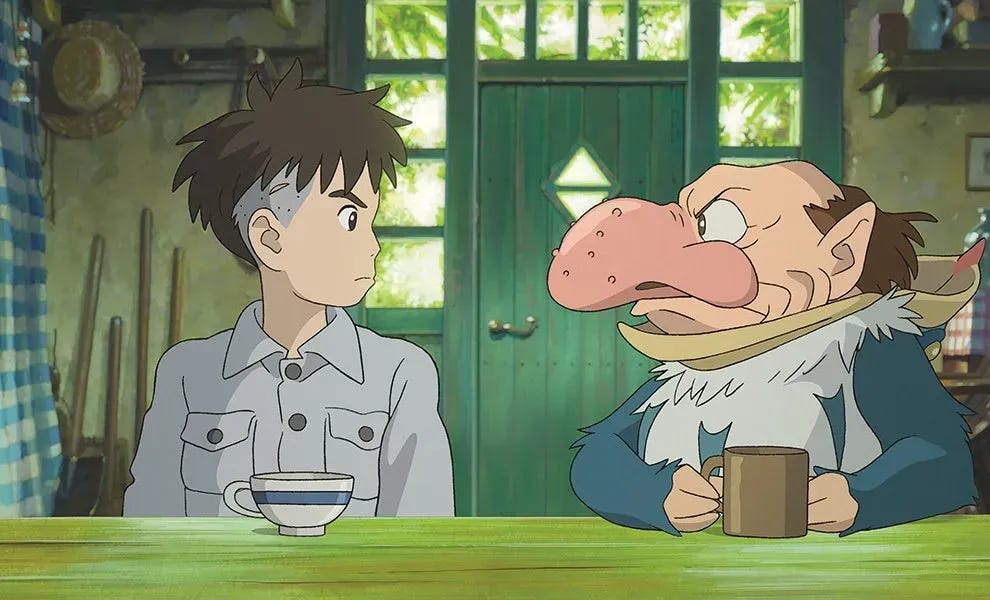

1. The Boy and the Heron

Japan, Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Is it inevitable, bordering on anticlimactic, that I would name the first new film in ten years from my all-time favorite director as the year’s greatest motion picture? Perhaps.

But this is, for me, undeniably the honest choice, because The Boy and the Heron is simply the movie I most loved watching in 2023 – the one whose visual storytelling most engrossed me, the one that sank me most deeply into something of a trance, wherein time and the outside world slipped away. I love the way this film thinks and moves and feels, the quiet but fierce confidence with which it brings us into its protagonist’s fractured world and aching inner life, and the profound dream logic with which the other world he enters unfolds.

This is the strangest and most challenging film Hayao Miyazaki has ever made, emotion sublimated on the surface while emotional logic abounds everywhere else. The Boy and the Heron is the most the director has ever fired from the hip, has imagined straight onto the canvas as though pictorially transcribing his dreams; narrative and geographic and diegetic coherence is prioritized far, far beneath the whims of the imagination. Miyazaki’s features have sometimes had moments of breakage, where the reality we have been watching slips away and we enter a poetic land where logic gives way to lyricism; I think of the plane graveyard in Porco Rosso, a line of lost pilots stretching on to infinity; or the journey to the Sixth Station in Spirited Away, where Chihiro takes a train across an eerie and unending ocean; or the mountainside cottage where a young Howl is visited by a star in Howl’s Moving Castle, a place that seems to exist in a dimension all its own. Moments like these can only be read symbolically, emotionally; we react to them like we do a piece of music, and Miyazaki certainly leans hard on composer Joe Hisaishi to bring these dreamscapes to life. If I were to try describing The Boy and the Heron in relation to Miyazaki’s canon, I would say it feels like one of these moments stretched out to feature length, its main character entering a series of these haunting, sublime expanses and journeying there for the whole of the run-time.

And what images these dreams are made of! It is entirely possible The Boy and the Heron is the single most lavish animated film ever produced, a proclamation that will only seem hyperbolic until one sees these images unravel for themself. The sheer number of frames of animation drawn for every character and on-screen element is staggering, the fluidity and ferocity of every movement genuinely astonishing. That it took seven years to animate is unsurprising when watching the finished product; the grandeur and complexity of the imagery is humbling to witness, and I do not know how to properly express just how extraordinary it is a film like The Boy and the Heron even exists. A purely auteurist vision, boldly and brazenly and defiantly singular, but operating on a scale of both material resources and raw imagination of which most filmmakers can scarcely dream.

To some degree, putting The Boy and the Heron – a film I have in no way begun fully to grapple with or wrap my ahead around, though it has consumed my thoughts for weeks – at number one is hedging my bets against the future, on the assumption that this is a movie I will carry with me and continue to discover for years and years to come: that whatever love I have for it now will only grow more intense in the years to come. It is a good assumption, I think, given my lifelong relationship with the films of Hayao Miyazaki. But it was also the movie I needed most this year, the film that came to me just as difficult questions about life and time and mortality were creeping into my mind; if it did not give me answers to those questions, which are of course unanswerable, then it gave me a powerful framework through which to think and feel their magnitude deeply. What more can we ask of art?

The Boy and the Heron is currently playing in theaters, in both Japanese with English subtitles and English dubbed versions. I can happily recommend both.

Read my full review of THE BOY AND THE HERON here.

If you like my reviews, I have 200 more for you – read my new book, 200 Reviews, in Paperback and on Kindle: https://a.co/d/bivNN0e

Support the show at Ko-fi ☕️ https://ko-fi.com/weeklystuff

Subscribe to JAPANIMATION STATION, our podcast about the wide, wacky world of anime: https://www.youtube.com/c/japanimationstation

Subscribe to The Weekly Stuff Podcast on all platforms: https://weeklystuffpodcast.com